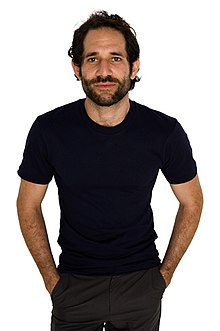

Dov Charney

Dov Charney | |

|---|---|

Dov Charney | |

| Born | January 31, 1969 |

| Occupation | Entrepreneur |

Dov Charney is a Canadian-born businessman and the founder and former CEO of American Apparel, a clothing manufacturer, wholesaler, and retailer.[1][2]

At American Apparel, Charney was involved in nearly every part of the business process from design and manufacturing to marketing.[3][3][4][5][6][7] At a time when the US garment industry had largely shifted to outsourcing manufacturing, Charney built American Apparel into a vertically integrated fashion company, where every aspect of the business—from design and manufacturing to distribution and marketing—was done from American Apparel’s headquarters in Los Angeles.[8][9] Charney was also responsible for American Apparel to be an early adopter of RFID tags on garments in 2007 in an effort to reduce theft and improve inventory control. [10][11][12] In addition, Charney pioneered the Made in USA sweatshop-free model of fair wages and a refusal to outsource manufacturing.[13][14][15]

In 2004, he was named Ernst and Young’s ‘Young and Ernst Entrepreneur of the Year’. Charney was titled ‘Retailer of the Year’ in the Michael Awards in 2008; an award which was previously given to Oscar de la Renta and Calvin Klein. He was given the title of ‘Man of the Year’ by the Apparel Magazine and the Fashion Industry Guild. In 2008 his brand was named ‘Label of the year’ by ‘The Guardian’.[16] The Los Angeles Times named him as one of the Top 100 powerful people in Southern California and in 2009, he was nominated as a Time 100 finalist by Time magazine.[17][18]

Charney has also been associated with several controversial lawsuits, including a lawsuit from film director Woody AllenCite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page). and sexual harassment lawsuits involving ex-employees.[19][20][21] In 2014 the issues resulting from some of these led to his dismissal as the company's chief executive officer.

Early and personal life

Charney was born in Montreal, Quebec. His father, Morris Charney, is an architect, and his mother, Sylvia Safdie, an artist.[22] Charney is a nephew of architect Moshe Safdie.[23] He attended Choate Rosemary Hall, a private boarding school in Connecticut[24] and St. George's School of Montreal.[25] Charney grew up with, and was influenced heavily by, the culture of Montreal and his Jewish heritage.[23][26] He briefly attended Tufts University. As a teenager, he "fell in love" with the United States, and drew a sharp contrast between American and Canadian cultures.[23] "...when he was 15, and "had fallen in love with the U.S. in the way only a Canadian kid can – because Americans had the freedom to choose from hundreds more kinds of sugar breakfast cereals than us." As a teenager, Charney was an admirer of American-made products.[27] As a teen, he became disillusioned with Quebec nationalism which was widespread during the 1980s.[28]

At an early age Charney showed signs of an entrepreneurial and independent spirit. According to the New York Times his first venture was selling rainwater he had collected in mayonnaise jars to his neighbors.[29] In 1980, The Canadian Jewish News published a story on Charney with a headline that read "11-Year-Old Schoolboy Edits His Own Newspaper.".[30] He sold these newspapers for 20 cents a copy near his school, only to be caught by a teacher and accused of panhandling and suspended from school.[29] As a child he was featured in the documentary 20th-Century Chocolate Cake, in which he discussed the economics of a summer camp he attended.[31][32]

Charney's teenage infatuation with the US inspired the aesthetics and name of the apparel company he later founded.[23][27] His first ventures in fashion began in high school, when he started importing Hanes and Fruit of the Loom t-shirts across the border to Canadian friends.[33] At Choate, he claims to have shipped as many as 10,000 shirts at a time, using a rented U-Haul truck to transport the goods.[34]

In 1987, he enrolled at Tufts University. While at Tufts, he continued to operate his business, but dropped out by 1990 to pursue the apparel business full-time.[35] He borrowed $10,000 from his father and moved to South Carolina to transition from importing T-shirts to manufacturing them.[36] In 1996, Charney's company restructured when it was unable to cover its debt and filed for Chapter 11.[24][37] On July 4, 1997, he went to Los Angeles.[38] By 2003, Charney had opened his first retail store and employed over 1,300 people.[39]

In 2004, he was named Ernst & Young's Entrepreneur of the Year and Apparel Magazine's Man of the Year.[40] In 2012, ABC News called Charney “one of the most controversial—and hyperactive—entrepreneurs in the country.[41]

Charney is also an investor in The Cardinal, a restaurant in New York City.[42][43]

American Apparel

Building the brand

In 1991, Charney began making basic T-shirts under the American Apparel brand. The initial T-shirts were made of simple 18-single jersey and were positioned to compete with the Hanes Beefy-T.[29] The primary market objective was to sell garments to screen printers and wholesale clothiers in the United States and Canada.[44] In 1997, as his design, the 'Classic Girl', built momentum, Charney transitioned manufacturing to Los Angeles. In 2000, American Apparel moved into its current 800,000 sq ft (74,000 m2) factory located in downtown Los Angeles.[45]

It was his aim in building American Apparel that it "live beyond [his] lifetime." According to Charney: "We'll be a heritage brand. It's like liberty, property, pursuit of happiness for every man worldwide. That's my America." [41]

Role as manufacturer/retailer/CEO

Charney is founder and CEO of American Apparel, but formerly went by the title of "Senior Partner."[46][47] He infused his personal progressive politics into the company brand paying factory workers between $13–18 USD/hr, offering low-cost, full-family healthcare for employees and taking a company position on immigration reform.[48][49][50] Workers are also allowed free international phone calls during work hours.[48] He claims to do this not for moral reasons but because it is a better business strategy.[51][52] He makes all product development and creative hiring decisions himself.[53]

Under Charney, American Apparel instituted "team manufacturing" which pools the strongest workers towards priority orders.[54] After its implementation, garment production tripled and required a less than 20% staff increase.[54] He formed the company as a domestic vertically-integrated manufacturer,[55] making him the largest manufacturer still producing garments in America.[56] Because of its vertically integrated and domestic manufacturing model, American Apparel's gross margins are actually significantly higher than other basic apparel brands. According to the company, its blended margins are roughly 70% (while GAP averages about 30% and luxury brands like Prada are between 65 and 70%.)[57]

Initially American Apparel was a wholesale brand but in 2003 it expanded into the retail market. Its first stores were in Montreal, New York City and Los Angeles.[48][58] By 2005, the company had over $200M in revenue.[29] Retail operations have grown to include 260+ retail stores. In 2008, he was named Retailer of the Year at the Michael Awards, a fashion industry mainstay.[59][60] The award has previously gone to Calvin Klein and Oscar de la Renta.[61]

In December 2006, Charney entered into an agreement to sell American Apparel for $360 million to the special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) Endeavor Acquisition as a way of taking the company public.[62] As a result of the agreement, Charney was named President and Chief Executive Officer of the publicly traded company known as American Apparel, Inc. He remained the majority shareholder, and all full-time employees of American Apparel were given up to 500 shares of stock depending on length of employment.[63]

Fashion and lifestyle

Charney is known for his passion for clothing.[64] His fashion sense is geared towards "young metropolitan adults."[65] The 'fit' of a shirt is something he often stresses.[66] He was named Man of the Year by both the Fashion Industry Guild and Apparel Magazine for his design work.[67] In 2008, The Guardian named American Apparel "Label of the Year".[68]

Charney lives in the Garbutt House, historic mansion atop a hill in Silverlake designed by Frank Garbutt, an early movie pioneer and industrialist.[29] The home is made entirely out of concrete due to Garbutt's deathly fear of fire. He is consumed with work, often sleeping in his office at the company's factory, leaving little separation between his personal and work life.[29] The house often functions as a dormitory for out of town workers doing business at the company headquarters.[29]

Advertising and brand management

Charney is directly involved in his company's design, branding, and advertising. His print campaigns are award-winning and among the most followed in the garment industry.[69] Charney has promoted a branding strategy that spotlighted his treatment of workers as a selling point for the company's merchandise, promoting American Apparel's goods as "sweatshop free." A banner on top of the downtown factory states "American Apparel is an Industrial Revolution."[56]

The company is also known for its simple and provocative ads featuring women, including employees. The subjects are often not but sometimes professional models, and often chosen personally by Charney from local hangouts and stores.[70] He shoots many of the advertisements himself.[71] His advertising has been criticized for featuring young, even teenage, models in sexually provocative poses. However, it has also been lauded for honesty and lack of airbrushing.[72][73] In 2005, Charney won the "Marketing Excellence Award" in the LA Fashion Awards.[74]

Annie Hall billboard lawsuit

In May 2007, American Apparel posted two billboards in New York and Los Angeles featuring a still image of actor Woody Allen from his 1977 movie Annie Hall.[19] They were removed at Allen's request within a week; he subsequently sued American Apparel on various grounds (including rights to privacy, and property rights).[19]

According to Charney, the billboard, which featured a photo of Allen as an Orthodox rabbi and "cheeky" Yiddish text ("The High Rabbi"), was a commentary on the tabloid coverage he received from several unproven sexual harassment lawsuits and the way that he and Allen—both Jews—had been treated by the media.[75][76] In an article published in The Guardian he wrote:

There are no words to express the frustration caused by these gross misperceptions, but this billboard was an attempt to at least make a joke about it.[77]

American Apparel's insurance company settled the case for U.S. $5 million (half of what Allen sought in damages)[78] on the eve of trial, the largest settlement of this type of lawsuit in New York State history.[79][80] Charney insisted that settlement was not his decision and expressed regret at being unable to defend in court what he believed to be speech protected by the First Amendment.[77]

Dismissal

During its routine meetings in March 2014, American Apparel's board learned that an arbitrator hearing one of the sexual harassment cases against Charney and the company had reached a decision in the case. While ruling that the main harassment claim had not been proven, the arbitrator found against the company and a Charney on a defamation claim, awarding $700,000 for that to Irene Morales, saying that Charney had failed to prevent a subordinate from posting naked pictures of her online. Up until then the board had steadfastly maintained that all the allegations against Charney, most of which were likewise settled in confidential arbitration proceedings, were not factually sufficient to constitute misconduct requiring disciplinary action.[81]

They also had strong financial reasons for replacing him. AA had posted losses in all but one of the previous 17 quarters, including $106 million during the preceding year, and the company had become a penny stock, Its financial options were limited—Charney's own portion of the company had been diluted from 45% to 27% during one effort to raise cash, which made it easier for the board to take him on. Some lenders refused to deal with the company at all while Charney was in charge, and those that did charged dearly; the interest rate on one of its major loans was 20%.[81]

With this now "established legal fact" in hand, the board began to quietly investigate Charney and prepare for the possibility of firing him, a move they anticipated he would resist vigorously. They worked closely with the company's law firm, Jones Day, to interview employees without Charney finding out. When they were done in June, the majority of the board confronted Charney with a throffer: either he quietly resigned as CEO and took a multimillion-dollar long-term position as a consultant, or they would fire him and make public why. He chose the latter.[81]

American Apparel publicly suspended Charney on June 18, 2014, stating that they would terminate him for cause in 30 days.[82][83] The company's board claimed at the time that it had "new information" which led it to finally fire Charney. "We have heard for years allegations and rumors in newspaper stories that were not sufficient to take action," said new co-chairman Allan Mayer. "But what came to our attention was not allegations and rumors but established fact." He declined to elaborate at that time. The board had just begun an investigation into how Charney responded to a 2011 lawsuit by a former employee who claimed he had held her against her will as a "sex slave", a suit settled in arbitration.[84]

Two days later, a company insider posted a "confession" to the social network Whisper asserting that the reasons for Charney's dismissal were "purely financial ... Everything else is bullshit. The board has nothing new." BuzzFeed got in touch with the poster through Whisper and was able to obtain the board's dismissal letter to Charney. It repeated the board's earlier allegation that he had allowed a subordinate to pose as Morales on a blog and make sexually provocative posts to him, which had apparently led to major punitive damages awarded to Morales by the arbitrator, calling this a breach of his fiduciary duty. Further in that vein, the board said, it head learned of an attempt to possibly suborn perjury in a "pending litigation matter". The letter also charged Charney with misusing corporate assets for personal gain, such as paying lucrative severance packages, bonuses and salary increases in exchange for silence from putative accusers as well as using corporate apartments himself and buying travel for family members with company funds, violating company policy by refusing to attend mandatory sexual harassment training sessions and disrupting them when others attended.[85]

As a result of Charney's behavior, the board claimed, the company's costs had increased unacceptably. "The company's employment practices liability insurance retention has grown to $1 million from $350,000 ... the premiums for this insurance are well outside of industry standards." His reputation had also hurt American Apparel's financing, as "many financing sources have refused to become involved with American Apparel as long as you remain involved with the company" and those that did had imposed "a significant premium for that financing in significant part because of your conduct." It gave him the 30-day suspension to "effect a cure" for these issues.[85] Charney demanded the board reinstate him, threatening to sue for age discrimination.[86]

In December 2014, Charney was terminated as a Chief Executive Officer after months of suspension. He will be replaced by Paula Schneider, president of ESP Group Ltd, company of brands like English Laundry, on January 5, 2015.[87] In December 2014, Charney told Bloomberg Businessweek he was down to his last $100,000 and that he was sleeping on a friend's couch in Manhattan.[88]

Lawsuits

Following his suspension as CEO in the summer of 2014, Charney teamed up with a hedge fund to buy stocks of the company to attempt a takeover.[89]

Following his firing as CEO, Charney, represented by lawyer Keith Fink[90] then launched a number of lawsuits against American Apparel, including two counts of defamation, which seek damages of up to $1 million in lost wages.[91][92] American Apparel counter-sued in May 2015, citing a "scorched earth campaign" made by Charney and an agreement detailing the rules of his departure.[93][94][95]

Temporary Restraining Order

In June of 2015, American Apparel was granted a restraining order against Charney.[96] According to a regulatory filing, "the order temporarily restrains him from breaching terms of a standstill agreement signed last year, including seeking removal of the company's board members and making negative statements in the press against the company or its employees".

Politics

In 2010, Charney made monetary contributions to the unsuccessful campaign of Gil Cedillo, a Californian Democratic Party candidate for Congress. In 2004 he contributed to a political action committee (PAC) that supported many Democratic candidates.[97]

Ethical views

In an interview with Vice.tv, Charney spoke out against the poor treatment of fashion workers in developing countries and refers to the practices as "slave labor" and "death trap manufacturing". Charney proposed a "Global Garment Workers Minimum Wage" as well discussed in detail many of the inner workings of the modern fast fashion industry practices that creates dangerous factory conditions and disasters like the 2013 Savar building collapse on 13 May, which had the death toll of 1,127 and 2,500 injured people who were rescued from the building alive.[98]

Controversy

Charney has been the subject of several sexual harassment lawsuits, at least five since the mid-2000s, that are either still pending or have settled or been dismissed.[99] Through early 2010, none of the accusations had been proven.[100][101] Some cases remain pending, but the remaining were dismissed, remanded to private arbitration, or “thrown out”.[76][102][103][104][105]

Charney maintained his innocence in all the lawsuits, telling CNBC that “allegations that I acted improperly at any time are completely a fiction."[106] The company and independent media outlets have publicly accused lawyers in the lawsuits against American Apparel of extortion and of "shaking the company down."[29][107][108][109] On the eve of trial in one case, the plaintiff confessed that she had not been subjected to sexual harassment and agreed to go to an arbitration hearing aimed at clearing Charney's name. However, the plaintiff failed to show up to the hearing and a ruling was unable to be reached. As a result, the $1.3 million settlement was dissolved and the matter reemerged as a negative media controversy for Charney.[110][111][112] The company was later sued by four ex-models for sexual harassment, including one separately named plaintiff who sued the company for $250 million.[29] The latter lawsuits were subject to much controversy when unsolicited nude photographs, consensual sexual text messages and requests for money surfaced.[107][113] Charney was accused of being responsible for these leaks in a later lawsuit.[114]

In 2004, Claudine Ko of Jane magazine[115] published an essay narrating multiple sexual exchanges that occurred between them while spending time with Charney. The article said that Charney consistently propositioned his employees. Charney admitted to using the word "sluts" in front of employees, in a deposition on another sexual harassment case, and denied that "slut" was a derogatory term.[72][116][117][118] The article's publication brought extensive press to the company and Charney, who later responded that he believed that the acts had been done consensually, in private and outside the article's bounds.[119][120][121][122]

In March 27, 2015, Dov Charney's attorney said, Charney plans to file a lawsuit claiming $40 million in damages for breaches of his employment contract, and more lawsuits are planned. As a result of that, American Apparel's shares were down 2.8 percent at 69 cents in that late morning trading day.[123]

References

- ^ [1] Bloomberg June 19, 2014

- ^ [2] Independent December 23, 2006

- ^ a b "Dov Charney, the hustler". The Economist. January 4, 2007. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ "Dov Charney: The hustler and his American dream". London: The Independent. December 23, 2006. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ La Ferla, Ruth (November 3, 2004). "Building a Brand By Not Being a Brand". New York Times. Retrieved March 21, 2008. "I think I was born a hustler", said Mr. Charney, the fast-talking founder of American Apparel, the rapidly expanding youth-oriented t-shirt chain. "I like the hustle.

- ^ Hoffman, Claire (December 20, 2006). "Clothier has designs on the world". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Evan, Carmichael. "Be Contrarian – Dov Charney". YoungEntrepreneur.com. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ Thompson, Authur. Crafting and Executing Strategy: The Quest for Competitive Advantage.

- ^ Martiosian, Sona (May 16, 2014). "American Apparel: Integrated Marketing Strategy". ""Slideshare"". Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ Monk, Ellen; Wagner, Bret. Concepts in Enterprise Resource Planning.

- ^ "RFID: Retail's superstar Technology". Technologies Solutions Group. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ^ (HTTP://RESOURCES.IMPINJ.COM/H/I/10330092-RETAIL-CASE-STUDY-AMERICAN-APPAREL/?UTM_SOURCE=FACEBOOK&UTM_MEDIUM=SOCIAL&UTM_CONTENT=2197747)

- ^ Joellen Perry; Marianne Lavelle (May 16, 2004). "Made in America". U.S. News and World Report. Retrieved November 27, 2007.

- ^ Endeavour Acquisitions Corp. SEC Proxy Statement Schedule 14A, June 5, 2007

- ^ Barco, Mandalit Dell. "American Apparel, an Immigrant Success Story". NPR. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ^ http://www.famous-entrepreneurs.com/dov-charney

- ^ "The Power Issue: The West 100". Los Angeles Times. August 13, 2006. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) [dead link] - ^ The 2009 Time 100 Finalists, Dov Charney

- ^ a b c American Apparel Settles with Woody Allen – Businessweek

- ^ Holson, Laura (March 23, 2011). "Chief of American Apparel Faces 2nd Harassment Suit". New York Times.

- ^ Li, Shan (December 5, 2012). "American Apparel's Dov Charney accused of choking, insulting employee". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Jewish Journal, Unfashionable Crisis, 2005-07-29

- ^ a b c d Silcoff, Mireille. "A real shirt-disturber: Dov Charney conquered America with his fitted t-shirts and posse of strippers". Saturday Post. Archived from the original on May 6, 2008. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- ^ a b Haskell, Kari (September 18, 2006). "An Interview With American Apparel Founder Dov Charney". Debonair Magazine. Archived from the original on April 6, 2008. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ St. George Alumni[dead link]

- ^ Morissette, Caroline (April 1, 2005). "Dov Charney at McGill". Bull and Bear.

- ^ a b Dov Charney (2007). American Apparel – Don Charney Interview (YouTube). CBS News.

{{cite AV media}}: External link in|medium= - ^ Choate Bulletin: Young Entrepreneurs[dead link] "increasingly suspect of Quebec nationalism and the sovereignty movement pervading the school system."

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Holson, Laura (April 13, 2011). "He's Only Just Begun to Fight". THe New York Times. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ "11-Year-Old Schoolboy Edits His Own Newspaper", DovCharney.com (PDF)

- ^ Gawker: Dov Enraged by Video of Kid Hustler Self

- ^ Young Dov Blackbook

- ^ A. Niedler, Alison (August 2000). "Angeleno Style". Apparel News. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ Carmichael, Evan. "Lesson #4: If You Can Dream It, You Can Do It". EvanCarmichael.com. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ Dean, Jason (September 2005). "Dov Charney, Like It or Not". Inc Magazine. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ Bracher, Trisha (December 21, 2003). "The T-Shirt Empire Breaking the Rules". London: The Observer. Retrieved March 21, 2008. "...he was too busy shifting product to actually complete his degree in American Studies.

- ^ Stossel, John (December 2, 2005). "Sexy Sweats Without the Sweatshop". ABC News. Retrieved March 21, 2008. The business went bankrupt and he filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

- ^ DovCharney.com My Name is Dov Charney

- ^ Bracher, Trisha (December 21, 2003). "The T-Shirt Empire Breaking the Rules". London: The Observer. Retrieved March 21, 2008. "With sales of $80 million this year (which are expected to double next year), it can afford to pay its 1,300-strong workforce...

- ^ Dov Charney (2004). Entrepreneur of the Year (YouTube). Ernst and Young.

- ^ a b American Apparel CEO Dov Charney: A Tarnished Hero? ABC News April 27, 2012

- ^ Miller, Jenny (August 2, 2011). "Dov Charney's Latest Role: Restaurant Investor". Grub Street New York.

- ^ Marx, Rebecca (August 2, 2011). "With the Cardinal, Dov Charney Penetrates the Restaurant Business". Village Voice.

- ^ Fonda, Daren (October 29, 2001). "Bring It On". Time Magazine. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ "Segment of Modern Marvels: Cotton". The History Channel via AmericanApparel.net. Retrieved November 25, 2007.

- ^ Inc.com's daily report on Dov Charney. September 2005

- ^ Charney, Dov. "Letters: American Apparel & United". The Nation. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ a b c La Ferla, Ruth (November 3, 2004). 23DRES.html?oref=login&8hpib "Building a Brand By Not Being a Brand". New York Times. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Palmeri, Christopher (June 27, 2005). "Living on the Edge at American Apparel". Businessweek. Retrieved March 22, 2008.

- ^ Dov Charney (2007). American Apparel – Don Charney Interview (YouTube). CBS News.

{{cite AV media}}: External link in|medium= - ^ Walker, Rob (August 1, 2004). "The Way We Live: 8/1/04: Consumed; Conscience Undercover". New York Times. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ Dobbs, Lou (February 9, 2004). "Kerry on the Attack; Putin Rival Disappears". CNN. Retrieved March 26, 2008. "A lot of people misunderstand it and think it was a moral decision. I think there is some morality to it. I mean, it is more fun to pay people well than pay people poorly. But it's also an economic one."

- ^ Dov Charney (2006). Charlie Rose. PBS.

- ^ a b Falsh, Derek (February 1, 2007). "Keep Your Fashion in Great Shape". The Pitt News. Retrieved April 28, 2008. "His team manufacturing..."

- ^ Greenberg, David (May 31, 2004). "Sew what? American Apparel founder Dov Charney wants to de-emphasize the fact he doesn't use sweatshop labor; he's just trying to sell a better T-shirt – People". Los Angeles Business Journal. Archived from the original on April 1, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ a b Dov Charney (2007). American Apparel – Don Charney Interview (YouTube). CBS News.

{{cite AV media}}: External link in|medium= - ^ BusinessInsider.com 4/10/12

- ^ DNR – All the Way to the Blank – Lee Bailey – March 22, 2004

- ^ "Dov Charney of American Apparel Named Retailer of the Year". PR News Wire. May 12, 2008. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- ^ American Apparel CEO Named Retailer of the Year[dead link] June 9, 2008. "I am privileged to accept this award in recognition of the hard work and creativity of the many people who have contributed to American Apparel's rapid growth and success".

- ^ Fashionista: Dov Charney, Winner[dead link] "Dov Charney was recently named "Retailer of the Year" for his work as the Creative Director and entrepreneur behind American Apparel.

- ^ Kang, Stephanie (December 19, 2006). "American Apparel Seeks Growth Through An Unusual Deal". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ American Apparel Announces Further Details of $39 Million Employee Stock Grant | Business Wire

- ^ Gladwell, Malcolm (April 24, 2000). "The Young Garmentos". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ Jamie Wolf (April 23, 2006). "And You Thought Abercrombie & Fitch Was Pushing It?". New York Times Magazine. Retrieved November 25, 2007.

- ^ "Charlie Rose: Dov Charney". Charlie Rose. July 14, 2007.

- ^ Olson, Debbi (December 17, 2007). "American Apparel chain makes Utah debut". The Enterprise. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ Vernon, Polly (November 30, 2008). "American Apparel Label of the Year". London: The Guardian. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ Daily Update: Top Of the Charts[dead link]

- ^ Rapoport, Adam (June 2004). "T (Shirts) and A". GQ.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) "What makes American Apparel's female models so appealing is that most of them are not models. They are girls whom Charney meets at bars, restaurants, trade shows—pretty much anywhere." - ^ Palmeri, Christopher (June 27, 2005). "Living on the Edge at American Apparel". Businessweek. Retrieved March 22, 2008. "Charney takes many of the photos himself, often using company employees as models as well as people he finds on the street."

- ^ a b Stossel, John (December 2, 2005). "Sexy Sweats Without the Sweatshop". ABC News. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ Morford, Mark (June 24, 2005). "Porn Stars in My Underwear". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 21, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Los Angeles Fashion Awards 2005

- ^ A Statement from Dov Charney[dead link] Daily Update, AmericanApparel.net May 2009

- ^ a b Sefton, Eliot (September 3, 2009). "Dov Charney's LA-based clothing company loses 1,600 staff and sees yet another advert banned". The First Post. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

Charney has been the subject of several, unproven, sexual harassment suits and claims to have been victimised by the media in the past. He said that he used Woody Allen in his company's ads because he wanted to draw attention to the way he and Allen – both high-profile Jews – had been treated.

[dead link] - ^ a b Charney, Dov (May 18, 2009). "Statement from Dov Charney, founder and CEO of American Apparel". London: The Guardian. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

- ^ Woody Allen and American Apparel settlement

- ^ NY Times, CJ Hughes and Sewell Chan, May 18, 2009

- ^ New York Times, CJ Hughes, May 18, 2009

- ^ a b c Harris, Elizabeth A.; Greenhouse, Steven (June 26, 2014). "The Road to Dov Charney's Ouster at American Apparel". The New York Times. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ http://www.mid-marketpulse.com/american-apparel-is-already-better-off-without-its-ceo/#!/

- ^ Riley, Charles (June 19, 2014). "American Apparel fires controversial CEO". CNN Money. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ Covert, James (June 20, 2014). "'Sex slave' led to ouster of American Apparel CEO". The New York Post. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ a b Maheshwari, Sapna (June 22, 2014). "Exclusive: Read Ousted American Apparel CEO Dov Charney's Termination Letter". BuzzFeed. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ Li, Shan; Chang, Andrea (June 22, 2014). "Dov Charney demands American Apparel job back or he'll sue, says lawyer". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ Dastin, Jeffrey (December 16, 2014). "American Apparel names new CEO, officially ousts founder". Reuters. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ^ http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-12-22/american-apparel-founder-says-he-s-down-to-last-100-000.html

- ^ http://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-american-apparel-charney-lawsuit-20150518-story.html

- ^ http://nypost.com/2015/05/19/charney-american-apparel-have-dueling-suits/

- ^ http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/style-notes-rick-owens-gets-789797

- ^ http://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-american-apparel-charney-lawsuit-20150518-story.html

- ^ http://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-american-apparel-charney-lawsuit-20150518-story.html

- ^ http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-05-18/american-apparel-sues-fired-ceo-over-campaign-to-retake-company

- ^ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/05/15/american-apparel-sues-dov-charney_n_7295020.html

- ^ http://www.businessinsider.com/r-american-apparel-gets-restraining-order-against-dov-charney-2015-6

- ^ "Dov Charney". CampaignMoney.com. January 21, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ^ VICE (May 29, 2013). "Dov Charney on Modern Day Sweat Shops: VICE Podcast 006". YouTube. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- ^ Holson, Laura M. (March 23, 2011). "Dov Charney of American Apparel Named in Harassment Suit". The New York Times.

- ^ Covert, James (March 28, 2010). "American Apparel Struggles to Stay Afloat". New York Post. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ Brennan, Ed (May 18, 2009). "Woody Allen reaches $5m settlement with head of American Apparel". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 22, 2009. Quote: "Charney has been involved in several highly publicised sexual harassment suits brought by former employees, none of which were proven.”

- ^ American Apparel CEO Dov Charney's 'Sex Slave' Lawsuit Thrown Out HuffingtonPost.com 03/22/2012 5:20 pm

- ^ Brennan, Ed (May 18, 2009). "Woody Allen reaches $5m settlement with head of American Apparel". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 22, 2009. Quote: "Charney has been involved in several highly publicised sexual harassment suits brought by former employees."

- ^ Judge Dismisses Sexual Harassment Lawsuit against American Apparel; No Further Legal Action in the Case Will Be Allowed; Plaintiff Receives No Money.

- ^ Covert, James (March 28, 2010). "American Apparel Struggles to Stay Afloat". New York Post. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ American Apparel CEO: Tattered, but Not Torn CNBC.com Jane Wells 4/10/12 “The company is also trying to recover from a litany of lawsuits against Charney, including a sex slave lawsuit that was thrown out last month”

- ^ a b Nolan, Hamilton (April 2011). "American Shakedown? Sex, Lies and the Dov Charney Lawsuit". Gawker. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ NAKED SHAKEDOWN: DOV CHARNEY IS THE VICTIM! HollywoodInterrupted.com December 2008

- ^ Chaudhuri, Saabira (December 2, 2008). "American Apparel Aims to Bring Down "Celebrity Ambulance Chasing" Lawyer". Fast Company. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ Heller, Matthew (October 28, 2008). "Fashion Mogul 'Fakes' Arbitration in Harassment Case". On Point. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

The 'confidential arbitration' was in fact a charade. One of Nelson's attorneys, the 2nd District said, later described it as 'a 'fake arbitration' designed to produce a press release calculated to blunt negative media attention.'

- ^ Slater, Dan (November 4, 2008). "The Story Behind American Apparel's Sham Arbitration". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 5, 2008.

The court went on to say that 'the proposed press release is materially misleading — among other things, no real arbitration of a dispute occurred and [the] plaintiff received $1.3 million in compensation.'

- ^ Stein, Sadie (October 31, 2008). "Tangled Webs: Dov Charney's Court Case is Totally Complicated". Jezebel. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

In response, Ms. Nelson's lawyer, Mr. Fink, devised a settlement agreement whereby his client would agree to certain stipulations amounting to a confession that her charges of sexual harassment were bogus, and that she had never been subject to any harassment or a hostile work environment.

- ^ "Money-hungry vixen sent me dirty emails', claims American Apparel CEO being sued". London: The Daily Mail. April 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ "Ex-workers say American Apparel posted nude pix online". Reuters. April 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ Nesvig, Kara (October 4, 2007). "Unkempt, Urban, Ubiquitous". Minnesota Daily. Retrieved April 28, 2008.[dead link] Archived at americanapparel.net

- ^ Sexy marketing or sexual harassment? – Dateline NBC | NBC News

- ^ ‘Jewish hustler’—potty mouth and pervert—means no offense | Jewish Journal

- ^ Claudine Ko, "Meet Your New Boss," Jane Magazine, June/July 2004 http://www.claudineko.com/storiesamericanapparel.html

- ^ "The company calls it "a social situation which...unfortunately was exploited in order to sell magazines." American Apparel CEO Trial Starts Today CNBC. Margaret Brennan. February 28, 2008.

- ^ "I've never done anything sexual that wasn't consensual", Charney says. The reporter, Claudine Ko, confirmed his take on events to BusinessWeek." Living on the Edge at American Apparel

- ^ "Within the context of a flirtatious conversation about sexuality and the pleasure Charney derives from masturbation with a willing partner, he decided to demonstrate for Ko, and it became a repeated motif in their later encounters. The article left a lasting impression of him as a boss who can't keep it in his pants", The New York Times "And You Thought Abercrombie and Fitch Was Pushing It"

- ^ "I was a younger man" he says, wearily. "The lines were blurred between paramour and reporter." The reporter has said that her tape recorder or notebook was in full view at all times and that the relationship was professional." Portfolio profile of Charney[dead link]

- ^ Rishika, Sadam (March 27, 2015). "Former American Apparel CEO Charney seeking $40 million in damages". Investing.com. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

External links

- Living people

- Canadian retail chief executives

- Canadian Jews

- Canadian fashion designers

- Businesspeople from Montreal

- Tufts University alumni

- Anglophone Quebec people

- Jewish fashion designers

- Companies that have filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy

- 1969 births

- Canadian company founders

- Canadian people of Israeli descent

- 21st-century Canadian businesspeople

- Choate Rosemary Hall alumni

- Canadian expatriates in the United States