Geology of Pluto

The geology of Pluto consists of the characteristics of the surface, crust, and interior of Pluto. Because of Pluto's distance from Earth, in-depth study from Earth is difficult. Because of this, many details about Pluto remained unknown until 14 July 2015 and onwards, when New Horizons flew through the Pluto system.[1]

Surface

(11 July 2015)

Pluto's surface is composed of more than 98 percent nitrogen ice, with traces of methane and carbon monoxide.[2] The face of Pluto oriented toward Charon contains more methane ice, whereas the opposite face contains more nitrogen and carbon monoxide ice.[3]

Maps produced from images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), together with Pluto's lightcurve and the periodic variations in its infrared spectra, indicate that Pluto's surface is very varied, with large differences in both brightness and color,[4] with albedos between 0.49 and 0.66.[5] Pluto is one of the most contrastive bodies in the Solar System, with as much contrast as Saturn's moon Iapetus.[6] The color varies between charcoal black, dark orange and white.[7] Pluto's color is more similar to that of Io with slightly more orange, significantly less red than Mars.[8]

Pluto's surface color has changed between 1994 and 2003: the northern polar region has brightened and the southern hemisphere has darkened.[7] Pluto's overall redness has also increased substantially between 2000 and 2002.[7] These rapid changes are probably related to seasonal condensation and sublimation of portions of Pluto's atmosphere, amplified by Pluto's extreme axial tilt and high orbital eccentricity.[7]

Soft-ice plains and glaciers

Sputnik Planum appears to be composed of ices more volatile that the water-ice bedrock of Pluto, including carbon-monoxide ice. A polygonal structure is visible, though this is obscured by what may be snow in some regions. No craters have been found. Glaciers of what is probably nitrogen ice can be seen flowing into valleys and craters at the edge of the plain; the valleys appear to have been formed through erosion. Snow or ice from the plain appears to have been blown or redeposited in a thin layer to the east and south of the plain, forming the large bright region of Tombaugh.

-

The northern edge of Sputnik Planum, with indications of flowing nitrogen ice, much like glaciers on Earth.

-

Polygonal ice patterns in southern Sputnik Planum. This region has wind-blown streaks which might attest to geysers. Pitting in the lower right is the result of sublimation.[9]

-

Concentration of frozen carbon monoxide in Sputnik Planum

Water-ice mountains

Mountains several kilometres high have been found along the southwestern and southern edges of Sputnik Planum. Water ice is the only ice detected on Pluto that is strong enough at Plutonian temperatures to support such heights.

Ancient cratered terrain

Cthulhu Regio and other dark areas have many craters and signatures of methane ice. The dark red color is thought to be due to tholins falling out of Pluto's atmosphere.

Northern latitudes

The mid-northern latitudes display a variety of terrain reminiscent of the surface of Triton. A polar cap consisting of methane ice "diluted in a thick, transparent slab of nitrogen ice" is somewhat darker and redder.[11]

-

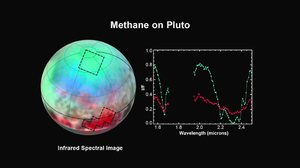

Distribution of methane ice on Pluto. Bright green is the polar cap; bright red is Balrog Regio.

-

Indications of complex geological features north of the dark equatorial regions

Internal structure

- 1. Frozen nitrogen[2]

- 2. Water ice

- 3. Rock

Pluto's density is 1.87 g/cm3.[13] Because the decay of radioactive elements would eventually heat the ices enough for the rock to separate from them, scientists think that Pluto's internal structure is differentiated, with the rocky material having settled into a dense core surrounded by a mantle of water ice.[14]

The diameter of the core is hypothesized to be approximately 1700 km, 70% of Pluto's diameter.[12] It is possible that such heating continues today, creating a subsurface ocean layer of liquid water some 100 to 180 km thick at the core–mantle boundary.[12][14][15] The DLR Institute of Planetary Research calculated that Pluto's density-to-radius ratio lies in a transition zone, along with Neptune's moon Triton, between icy satellites like the mid-sized moons of Uranus and Saturn, and rocky satellites such as Jupiter's Io.[16]

See also

References

- ^ Brown, Dwayne; Buckley, Michael; Stothoff, Maria (15 January 2015). "January 15, 2015 Release 15-011 - NASA's New Horizons Spacecraft Begins First Stages of Pluto Encounter". NASA. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ a b Owen, Tobias C.; Roush, Ted L.; Cruikshank, Dale P.; et al. (1993). "Surface Ices and the Atmospheric Composition of Pluto". Science. 261 (5122): 745–748. Bibcode:1993Sci...261..745O. doi:10.1126/science.261.5122.745. PMID 17757212.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (11 February 1999). "Pluto regains its place on the fringe". MSNBC. Retrieved 20 March 2007.

- ^ Buie, Marc W.; Grundy, William M.; Young, Eliot F.; et al. (2010). "Pluto and Charon with the Hubble Space Telescope: I. Monitoring global change and improved surface properties from light curves". Astronomical Journal. 139 (3): 1117–1127. Bibcode:2010AJ....139.1117B. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/139/3/1117.

- ^ Hamilton, Calvin J. (12 February 2006). "Dwarf Planet Pluto". Views of the Solar System. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- ^ Buie, Marc W. "Pluto map information". Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ a b c d Villard, Ray; Buie, Marc W. (4 February 2010). "New Hubble Maps of Pluto Show Surface Changes". News Release Number: STScI-2010-06. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ Buie, Marc W.; Grundy, William M.; Young, Eliot F.; et al. (2010). "Pluto and Charon with the Hubble Space Telescope: II. Resolving changes on Pluto's surface and a map for Charon". Astronomical Journal. 139 (3): 1128–1143. Bibcode:2010AJ....139.1128B. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/139/3/1128.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (17 July 2015). "Pluto Terrain Yields Big Surprises in New Horizons Images". New York Times. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ Gipson, Lillian (24 July 2015). "New Horizons Discovers Flowing Ices on Pluto". NASA. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b c

Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.005 , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.005instead. - ^ Pluto – Universe Today

- ^ a b "The Inside Story". pluto.jhuapl.edu – NASA New Horizons mission site. Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "What is Pluto made of?". Space.com. 20 November 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ DLR Interior Structure of Planetary Bodies DLR Radius to Density The natural satellites of the giant outer planets...

![Polygonal ice patterns in southern Sputnik Planum. This region has wind-blown streaks which might attest to geysers. Pitting in the lower right is the result of sublimation.[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/36/Troughs_in_Sputnik_Planum_by_LORRI.jpg/300px-Troughs_in_Sputnik_Planum_by_LORRI.jpg)