Emil Milan

Emil Milan | |

|---|---|

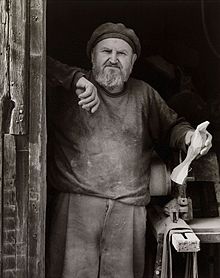

Emil Milan c. 1980. | |

| Born | May 17, 1922 |

| Died | April 5, 1985 |

| Education | Art Students League of New York 1946–1951 |

| Occupation(s) | Artist, designer, sculptor, woodworker, teacher |

| Known for | Wooden bowls, birds, art, and accessories |

| Style | Midcentury modern, biomorphism |

| Signature | |

| |

Emil Milan ('ɛmil Mɪ'lɑːn; May 17, 1922 – April 5, 1985) was an American woodworker known for his carved bowls, birds, and other accessories and art in wood. Trained as a sculptor at the Art Students League of New York, he designed and made wooden ware in the New York City metropolitan area, and later in rural Pennsylvania where he lived alone and used his barn as a workshop. Participating in many woodworking, craft, and design exhibits of his day, his works are in the Smithsonian American Art Museum and Renwick Gallery, the Yale Art Gallery, the Center for Art in Wood, the Museum of Art and Design, and many private collections. Once prominent in midcentury modern design, Milan slipped into obscurity after his death.[1] His legacy has been revived by an extensive biographical research project that has led to renewed interest in his life, work, and influence.[a]

Early life and education

Milan was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey[b] and graduated from Abraham Clark High School in Roselle in 1940.[2] He took up wood carving at an early age and learned shop skills from his father, who was an industrial welder. Attesting to his skill, one of his teachers paid him to carve a small wooden cow for her veterinarian brother.[3]

He enlisted in the US Army in 1942, served as a Military Policeman in Europe during WWII, landing on Omaha Beach just after the invasion and advancing across France with the 1st Army. During that time, he continued occasional carving and produced provocative female figures for his fellow soldiers that he called "3D Pinups."[4] He was honorably discharged in Monmouth, NJ on November 17, 1945.

Supported by the GI Bill, he studied art and sculpture at the Art Students League of New York starting in 1946, enrolling in classes taught by noted artists Will Barnet, Jose De Creeft, William Zorach, and John Hovannes.[5] The sculpture courses focused on the tools and techniques of modern sculpture and on the human figure.[6] Both de Creeft and Zorach taught then new methods of direct carving (taille directe) and both produced stylized forms, particularly of women. De Creeft also produced works in wood.[7]

Early career

After leaving the Art Students League in 1951, Milan continued carving figural works and what he called “functional sculpture” in wood (bowls, trays, spoons, and other accessories) at his parents' home in Roselle. During that time he met Myra and Stan Buchner who were forming a new craft association called New Jersey Designer Craftsmen, and he began selling his works in the group’s Christmas shows. The annual Christmas exhibition at the Newark Museum of Art was also a major sales outlet for Milan between 1953 and 1964.[8]

A cutting board with a scoop and a carved bowl made by Milan were selected for the landmark exhibit Designer Craftsmen, USA 1953.[9] The exhibit toured the Brooklyn Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the San Francisco Museum of Art from October, 1953 through August, 1954, then traveled throughout the United States for a year.

In 1953, the Buchners partnered with David Kittredge to form a woodworking business called Buckridge Contemporary Design, located in Orange, NJ. Milan was the designer, set up and ran the shop, and supervised a small group of workers. The shop produced functional wooden tableware and decorative art in wood, notably stylized fish and birds.[10] These works were sold in specialty shops and department stores in the New York City metropolitan area. Hammacher-Schlemmer, for example, marketed a Table Talk line of wooden ware crafted by Milan.[11] Other retailers included Bonniers, McCutcheons, and Saks Fifth Avenue.

Buckridge items were included in the model home displays of House Beautiful magazine that were shown at international exhibitions in 1955–56 in Paris, Milan, Barcelona, and Bari, Italy.[12] A 1956 article in the New York Times by Home section editor Betty Pepis also featured objects produced at Buckridge.[13] The business was disbanded by late 1959.

In 1957, a carved tray and two spoons by Emil Milan appeared in the Design Wood exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Craft (now Museum of Art and Design) in New York City. The three works were purchased by the American Craft Council for the Museum's permanent collection.[14] The May/June 1957 issue of the American Craft Council's magazine Craft Horizons had a feature article on Emil Milan, focusing on his tools and methods of work.[15] Also in that issue, Milan's bird shaped hors d’oeuvres server was featured in the Designers Showcase section of the magazine.

The then American Craftsmen's Council launched its traveling exhibit program in 1960 with a "Communication in Craft" exhibit focusing on wood and on fiber arts. Three works by Milan were selected for the "Craftsmanship in Wood" display.[16] The exhibit started at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (NYC), January 8 – February 15, 1960, then travelled to museums, schools, and craft groups across the US. The exhibit included leading woodworkers of the day such as Wharton Esherick, Joyce and Edgar Anderson, Sam Maloof, Bob Stocksdale, and George Nakashima, as well as leading designers such as Charles Eames, James Prestini, and Tapio Wirkkila.[17]

- Gallery: Functional Sculpture

-

Small salt bowl and spoon

-

Walnut pencil holder

-

Salad servers

-

Bubinga tray

-

Two part walnut bowl

Move to rural Pennsylvania

In 1961, Milan bought a derelict dairy farm and moved to a rural setting near Thompson, Pennsylvania. He lived and worked there for the rest of his life. During this period he sold his works directly to customers from his workshop and through retail shops .[c] Fifteen of his pieces were included in the exhibit entitled Craftsmanship Defined held at the Philadelphia Museum College of Art, March 13 – April 18, 1964.[18] A picture of Milan holding a large bowl he carved from African mahogany was on the cover of the Newark News Sunday Magazine, January 9, 1966. In October 1969, he participated in the Smithsonian Institution’s Cooperative Craft Exhibit in Washington, DC. In July 1969, he was an invited exhibitor at the Central Pennsylvania Festival of the Arts in State College, PA.[19] Also in 1969, he was commissioned to make the gavel and strikeplate for the President of the National Extension Association of Family and Consumer Sciences.[20] Starting in October 1969, a 30-minute color documentary entitled Emil Milan: Craftsman aired for about six months on Educational TV channels in Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, and Pasadena, CA. A copy of the tape has not yet been found.[21]

- Gallery: Art In Wood

-

Chloe

-

Whale In A Wave

-

Zebrawood bird

-

Female figure

-

Bubinga bird

Teaching

After moving to Pennsylvania, Milan increased his teaching of woodworking, both at his barn studio and regionally. He taught at Peter’s Valley Craft Center (now Peters Valley School of Craft in Layton, New Jersey) from the Center's inaugural year, 1971, through 1984. He was an Associate Instructor in 1971–72 and a Resident Instructor in 1973.[22] He taught methods he used carving sculptural forms and functional objects and about varieties of wood species, wood structure, and tool use and care.[23] His students varied widely in experience and skill, from newcomers to emerging professional woodworkers. He taught by demonstration, encouraging individual creative expression and innovation in using both hand tools and power tools.

In the late 1960's the Penn State Agricultural Extension Service hired Milan as an instructor.[24] The Extension Service, funded by the federal Manpower Development and Training Act, employed him to teach woodworking skills in rural areas to rekindle the craft industry in Pennsylvania.[25] An article in Science for the farmer, featuring Milan on the cover, described the unusual program.

For several years in the 1970’s, Milan did woodworking demonstrations at the Harford Fair (PA). He did demonstrations and workshops at high schools in Pennsylvania including Sullivan County High School (1970–1979), Carbon County Technical School (1970), Montrose High School (1979).

Honduras 1964–65

In fall 1964, Milan joined noted furniture makers Joyce and Edgar Anderson and designer Gere Kavanaugh for several months in Honduras in a USAID program. The goal was to train local people to make products from indigenous woods for sale in the US market. He designed prototypes of functional and art objects as teaching aids and taught woodworking in Tegucigalpa.[26]

Later career

A cutting board and scoop of Milan’s was selected for the Smithsonian Institution’s landmark Craft Multiples exhibit at the Renwick Gallery July 4, 1975 to February 16, 1976.[27] The exhibit then traveled the United States for three years. These works are in the permanent collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery.[28]

Emil was an invited participant and demonstrator at a conference entitled Wood ’79: The State of the Art, held on the campus on SUNY Purchase October 5–7, 1979.The event focused on studio furniture and high end woodworking and attracted more than 400 participants, including many leading woodworkers of the day.[29] In August 1980, the only solo show of Emil Milan’s work in his lifetime was held at Robert Stark’s Susquehanna Studio in Uniondale, PA.

Use of wood and other materials

Throughout his career, Milan used a wide range of woods including domestic hardwoods such as maple, walnut, and black cherry, as well as exotic imported species such as zebrawood, padouk, cocobolo, bubinga, lapacho, and rosewood.[30] Buckridge items made from imported woods commanded higher prices.[31] He periodically capitalized on grain patterns, intensive figure, and contrasting heartwood and sapwood colors as design elements in his works.[32][33] Silver components occasionally were added to functional wooden works, and he made a few cheese boards with flat ceramic inserts as cutting surfaces.[34] He was frugal with wood and used scraps to make saleable functional and art objects. Cutouts from large bowl forms, for example, were used to make fish, birds, and abstract sculptures, and the remaining pieces were used to make small salt bowls and spoons.[35]

- Gallery: Use of Materials

-

Two tone Padouk bowl

-

Jacaranda birds

-

Walnut bird

-

Nut bowl with silver base

-

Cheese board with ceramic insert

Tools and techniques

Milan was an innovator in woodworking methods and a pioneer in advocating the integrated use of hand and power tools, focusing on the excellence of the final product.[36] An article in the American Craft Council's magazine Craft Horizons in 1957 featured Milan's use of both hand tools and power tools to “...still achieve a handmade look.” [37]

Craftsmen should be able to use all kinds of tools and machines. It doesn't matter what tools you use. But it does matter that the thing you produce be the best that can be done. The important thing is the result.

— Emil Milan, Designer Craftsmen USA, 1953

A sequence of pictures showed how he used a drill press to rapidly remove wood inside concave parts of bowls, trays, and spoons. He would then refine the roughed out concave forms with a mallet and wood gouges, before power sanding with flexible disk attachments—thus using a power tool, hand tools, and then another power tool in rapid succession.

He devised tools and techniques for increasing speed and efficiency without sacrificing workmanship. He made flat templates of his commonly produced works to rapidly transfer outlines onto wood blanks. A 12-station duplicating machine was in use at the Buckridge shop to quickly rough out multiple copies of production items. He had several tools made for him by blacksmiths at Peter’s Valley Craft Center, for example, and in at least one case made a wooden prototype of a specialized gouge to communicate his exact requirements.[38]

Milan designed and built a multipurpose drum- and belt-sander, dubbed the “Emil Machine” by his woodworking colleagues.[39] It had interchangeable pneumatic drums of different sizes and a long slack belt. The tension on the belt could be adjusted to achieve a shape that matched the outside curve of a work. A detatchable plate could be installed below the upper belt to sand flat surfaces. These power sanding methods were used to rapidly shape the work and to refine and smooth the piece before applying laquer or linseed oil. A crude slack belt sanding machine, possibly designed and built by Milan, was in use at the Buckridge shop in the 1950’s. [40]

He routinely used the bandsaw as a carving tool, standing a slab up on edge and slicing off long thin curves of wood in closer and closer approximation of the final desired form.[41] This risky procedure violates basic safety tenants of bandsaw use that insist that the stock must have a stable flat surface held firmly against the table.[42] He demonstrated his sanding and bandsaw techniques to other professional woodworkers at the Wood '79 conference held at SUNY Purchase, October 5–7, 1979.[29]

Later life and death

Milan continued to live alone in Thompson PA in the 1980s, but his health began to deteriorate. He died April 5, 1985 (age 62) and is buried in Thompson, PA.

Recent interest and exhibits

Interest in Emil Milan has been renewed in recent years due to a biographical research project funded by the Center for Craft, Creativity, and Design that yielded an extensive archival report documenting Emil’s life and work,[2][43] and an article in Woodwork magazine in 2010.[44] Since then, there has been increased media attention, two major exhibits, and an academic symposium focused on Milan.

An exhibit entitled Emil Milan: Midcentury Designer Craftsman was held at the Henry Gallery on the campus of Penn State Great Valley in Malvern, PA June 9 – September 26, 2014. The first solo exhibit of Milan’s works in over 30 years, it included 88 objects curated by Phil Jurus, Barry Gordon, and Norm Sartorius. The exhibit was previewed in Woodwork magazine in January 2014[45] and was the topic of Erika Funke's Artscene radio show on WVIA-FM.[46]

The works traveled to the Center for Art in Wood in Philadelphia for an exhibit curated by Jennifer Zwilling entitled Rediscovering Emil Milan and his Circle of Influence (November 7, 2014 – January 24, 2015). The exhibit added works by 19 artists, students, and colleagues influenced directly or indirectly by Milan. This expanded exhibit was featured in the January 2015 issue of American Art Collector[47] and is the topic of a short documentary by filmmaker John Thornton.[48]

A symposium entitled Connecting Circles on Milan’s life, work, and influence, sponsored by the Center for Art in Wood, was held January 17, 2015 at the studios of WHYY-TV in Philadelphia. Presenters included Milan experts Sartorius, Gordon, and Jurus; Elizabeth Agro from the Philadelphia Museum of Art; professional curators Jennifer Zwilling (Philadelphia) and Jennifer Scanlan (New York); Kristin Muller from Peters Valley School of Craft (NJ); Andrew Willner, professional woodworker and colleague of Milan's; and Milan's student and accomplished artist in wood Rebecca Dunn Penwell.

Notes

- ^ Funded by a grant from the Center for Craft, Creativity, and Design (CCCD) in Asheville, NC, the Emil Milan Research Project has been led by Norm Sartorius, Barry Gordon, and Phil Jurus with the goal of documenting Milan's life, work, and influence on the field. A research report containing extensive archival material was prepared in 2011 and is available at the CCCD and other repositories including the American Craft Council Library (Minneapolis), Smithsonian's Renwick Gallery (DC), the Yale University Art Gallery (New Haven), the Museum for Art and Design (New York), and the Center for Art in Wood (Philadelphia).

- ^ The birth certificate of Emil B. Milan (No.1518), issued by the Registrar, Office of Vital Statistics, City Hall, Elizabeth, NJ shows his date of birth as May 17, 1922 and location at 62 S. Second St. (i.e., he was born at home). The family moved shortly thereafter to Roselle, NJ.

- ^ Retail shops included the store at the Peter’s Valley Craft Center; two locations of Elliot Herman’s Peasant Shop (Philadelphia and Bryn Mawr); The Craft Barn in the town of Florida, NY; Ursells in Washington, DC; the Orange Door in State College, PA; and Phil and Sandye Jurus’ shops: Sticks and Stones in Eagles Mere, PA, the Village Silversmith Shop in Towson, MD; the Gallery of Contemporary Crafts in Lutherville, MD; and Jurus, Ltd. in Lutherville, Md. (see Research Project Report, 2011, 7 page section “Milan's sales through stores and galleries.”)

References

- ^ Gordon, B., Sartorius, N., and Jurus, P. (2010). Emil Milan: The (re)-introduction of a seminal American woodworker. Woodwork, Winter 2010, PPP. 64-68.

- ^ a b Sartorius, N., Gordon, B., and Jurus, P. (2011). The Emil Milan Research Project. Chapter on military service. p.1 (separately paginated). Report available from the Center for Craft, Creativity, and Design, Asheville, NC.

- ^ Worthington, K. (1979) Interview with Emil Milan, Sullivan Review, March 29, 1979.

- ^ Research Project Report, 2011, Chapter on "Military Service" (separately paginated), p.2-4

- ^ Membership record of student Emil Milan, the Art Students League of New York, 215 West 57th Street, New York, NY 10019

- ^ Research Project Report (2011). Chapter on The influence of the Art Students League of New York. (separately paginated).

- ^ Campos, J. (1972) Jose de Creeft. New York: Da Capo Press. Appendix (unpaginated). Figures 229-258.

- ^ Research Project Report (2011). Five page section of the Newark Museum of Art Christmas Shows.

- ^ Designer Craftsmen USA. Exhibit Guide. (1953).

- ^ Buckridge Contemporary Design (video). www.youtube.com/watch?v=XgUQvGh7qAs

- ^ Hammacher-Schlemmer ad for “Table Talk” woodenware. New Yorker magazine, October 30, 1954

- ^ House Beautiful (magazine). July 1955

- ^ Betty Pepis, “Wood accessories sculpted in new shapes,” New York Times, Home Section, March 17, 1956.

- ^ Museum of Art and Design, permanent collection. See collections.madmusuem.org

- ^ “Emil Milan,” Craft Horizons, June 1957, Vol. XVII, No. 3, pp. 37-39.

- ^ "Visual Communication," Craft Horizons, 1960 (Jan/Feb Issue) pp. 39, 42-43.

- ^ Craft Horizons, 1960, pp. 42-43

- ^ Craftsmanship Defined: An Exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum College of Art, March 13 – April 18, 1964. See collections.library.uarts.edu/cdm/ref/collection/pubsarchive/id/37398

- ^ Daily Collegian, (Penn State University student newspaper), July 10, 1969

- ^ Gavel and strikeplate of the NEAFCS President (Picture with explanatory caption). www.neafcs.org/assets/documents/history/1969.pdf

- ^ Research Project Report, 2011, TV listings for the 30-minute color documentary on Emil Milan:

- ^ Perry, Kevin, C. Peter’s Valley or Bevens, NJ: Work In Progress. Unpublished history of Peter’s Valley Craft Center.

- ^ Mimeographed handout for Emil Milan’s workshop at Peter’s Valley Craft Center (undated, unpaginated. (1970s)

- ^ Science for the farmer.(1967). Periodical publication of the College of Agriculture, Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA. Picture of Emil Milan on the cover and a two-page article (unpaginated).

- ^ Research Project Report, 2011, chapter on teaching

- ^ Oral history interview with Joyce and Edgar Anderson, September 17–19, 2002. Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art. www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-edgar-and-joyce-anderson-13240 Accessed March 20, 2015.

- ^ Cutting Board and Scoop by Emil Milan, American Art Museum, americanart.si.edu/collections/search/artwork/?id=17405

- ^ Exhibit Guide for Craft Multiples, Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1975.

- ^ a b Kelsy, John. Review of the Wood ’79 conference. Woodworking Magazine, Jan/Feb 1980.

- ^ Craft Horizons, 1957. p.37

- ^ Research Project Report, 2011, Buckridge wholesale price list. Appendix III, p 24.

- ^ Craft Horizons, 1957, p.37

- ^ Gordon et al. 2010. p.68

- ^ Research Project Report, 2011, Chapter on 'Secondary Market" (separate pagination) p.3

- ^ Gordon et al., 2010, p.67

- ^ "Circle of Influence," American Art Collector, January 2015 (Issue 111). p. 165

- ^ ’’Craft Horizons’’ 1957. p. 38

- ^ Research Project Report, Interview with Vincent Bilotta, May 2, 2011.

- ^ Research Project Report, 2011, Chapter on "Methods of work." p.7

- ^ Research Project Report. 2011. Chapter "A study in contrasts." p. 6

- ^ Gordon et al. (2010). p.66

- ^ Duginske, M. (2007). “Bandsaw Safety Procedures” in The new complete guide to the bandsaw (p.9). Fox Chapel Publishing, East Petersburg, PA.

- ^ Shaykett, J. (2011). Unearthing the Story of Emil Milan: A Research Project with Heart. American Craft Council, Minneapolis, MN. craftcouncil.org/post/unearthing-story-emil-milan-research-project-heart

- ^ Gordon, B., et al, 2010, Woodwork magazine.

- ^ Gordon, B. (2014) Emil Milan Exhibit. Woodwork, Winter 2014. p. 7.

- ^ ArtScene radio show August 8, 2014.

- ^ Circle of Influence, American Art Collector, January 2015, (Issue# 111) pp. 164-165

- ^ Finding the Artist Emil Milan. Documentary film by John Thornton (18 m 36s). Accessed March 20, 2015. www.youtube.com/watch?v=vHtNa46SaaI