Hippocratic Oath

The Hippocratic Oath is an oath historically taken by physicians. It is one of the most widely known of Greek medical texts. In its original form, it requires a new physician to swear, by a number of healing gods, to uphold specific ethical standards. The oath is the earliest expression of medical ethics in the Western world, establishing several principles of medical ethics which remain of paramount significance today. These include the principles of medical confidentiality and non-maleficence. As the seminal articulation of certain principles that continue to guide and inform medical practice, the ancient text is of more than historic and symbolic value. Swearing a modified form of the oath remains a rite of passage for medical graduates in many countries.

Hippocrates is often called the father of medicine in Western culture.[1] The original oath was written in Ionic Greek, between the fifth and third centuries BC.[2] It is usually included in the Hippocratic Corpus.

Text of the oath

Earliest surviving copy

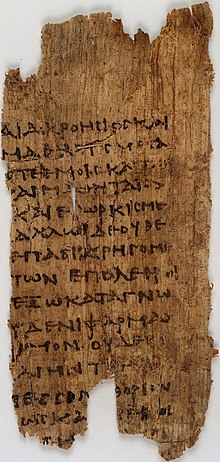

The oldest partial fragments of the oath date to circa 275 AD. [3] The oldest extant version dates to roughly the 10th-11th century, held in the Vatican Library.[4] A commonly cited version, dated to 1595, appears in Koine Greek with a Latin translation.[5][6] In this translation, the author translates "πεσσὸν" to the Latin "fœtum."

The Hippocratic Oath, in Greek, from the 1923 Loeb edition, and then followed by the English translation:

ὄμνυμι Ἀπόλλωνα ἰητρὸν καὶ Ἀσκληπιὸν καὶ Ὑγείαν καὶ Πανάκειαν καὶ θεοὺς πάντας τε καὶ πάσας, ἵστορας ποιεύμενος, ἐπιτελέα ποιήσειν κατὰ δύναμιν καὶ κρίσιν ἐμὴν ὅρκον τόνδε καὶ συγγραφὴν τήνδε:

ἡγήσεσθαι μὲν τὸν διδάξαντά με τὴν τέχνην ταύτην ἴσα γενέτῃσιν ἐμοῖς, καὶ βίου κοινώσεσθαι, καὶ χρεῶν χρηΐζοντι μετάδοσιν ποιήσεσθαι, καὶ γένος τὸ ἐξ αὐτοῦ ἀδελφοῖς ἴσον ἐπικρινεῖν ἄρρεσι, καὶ διδάξειν τὴν τέχνην ταύτην, ἢν χρηΐζωσι μανθάνειν, ἄνευ μισθοῦ καὶ συγγραφῆς, παραγγελίης τε καὶ ἀκροήσιος καὶ τῆς λοίπης ἁπάσης μαθήσιος μετάδοσιν ποιήσεσθαι υἱοῖς τε ἐμοῖς καὶ τοῖς τοῦ ἐμὲ διδάξαντος, καὶ μαθητῇσι συγγεγραμμένοις τε καὶ ὡρκισμένοις νόμῳ ἰητρικῷ, ἄλλῳ δὲ οὐδενί.

διαιτήμασί τε χρήσομαι ἐπ᾽ ὠφελείῃ καμνόντων κατὰ δύναμιν καὶ κρίσιν ἐμήν, ἐπὶ δηλήσει δὲ καὶ ἀδικίῃ εἴρξειν.

οὐ δώσω δὲ οὐδὲ φάρμακον οὐδενὶ αἰτηθεὶς θανάσιμον, οὐδὲ ὑφηγήσομαι συμβουλίην τοιήνδε: ὁμοίως δὲ οὐδὲ γυναικὶ πεσσὸν φθόριον δώσω.

ἁγνῶς δὲ καὶ ὁσίως διατηρήσω βίον τὸν ἐμὸν καὶ τέχνην τὴν ἐμήν.

οὐ τεμέω δὲ οὐδὲ μὴν λιθιῶντας, ἐκχωρήσω δὲ ἐργάτῃσιν ἀνδράσι πρήξιος τῆσδε.

ἐς οἰκίας δὲ ὁκόσας ἂν ἐσίω, ἐσελεύσομαι ἐπ᾽ ὠφελείῃ καμνόντων, ἐκτὸς ἐὼν πάσης ἀδικίης ἑκουσίης καὶ φθορίης, τῆς τε ἄλλης καὶ ἀφροδισίων ἔργων ἐπί τε γυναικείων σωμάτων καὶ ἀνδρῴων, ἐλευθέρων τε καὶ δούλων.

ἃ δ᾽ ἂν ἐνθεραπείῃ ἴδω ἢ ἀκούσω, ἢ καὶ ἄνευ θεραπείης κατὰ βίον ἀνθρώπων, ἃ μὴ χρή ποτε ἐκλαλεῖσθαι ἔξω, σιγήσομαι, ἄρρητα ἡγεύμενος εἶναι τὰ τοιαῦτα.

ὅρκον μὲν οὖν μοι τόνδε ἐπιτελέα ποιέοντι, καὶ μὴ συγχέοντι, εἴη ἐπαύρασθαι καὶ βίου καὶ τέχνης δοξαζομένῳ παρὰ πᾶσιν ἀνθρώποις ἐς τὸν αἰεὶ χρόνον: παραβαίνοντι δὲ καὶ ἐπιορκέοντι, τἀναντία τούτων.

I swear by Apollo Physician, by Asclepius, by Hygieia, by Panacea, and by all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will carry out, according to my ability and judgment, this oath and this indenture.

To hold my teacher in this art equal to my own parents; to make him partner in my livelihood; when he is in need of money to share mine with him; to consider his family as my own brothers, and to teach them this art, if they want to learn it, without fee or indenture; to impart precept, oral instruction, and all other instruction to my own sons, the sons of my teacher, and to indentured pupils who have taken the physician’s oath, but to nobody else.

I will use treatment to help the sick according to my ability and judgment, but never with a view to injury and wrong-doing. Neither will I administer a poison to anybody when asked to do so, nor will I suggest such a course. Similarly I will not give to a woman a pessary to cause abortion. But I will keep pure and holy both my life and my art. I will not use the knife, not even, verily, on sufferers from stone, but I will give place to such as are craftsmen therein.

Into whatsoever houses I enter, I will enter to help the sick, and I will abstain from all intentional wrong-doing and harm, especially from abusing the bodies of man or woman, bond or free. And whatsoever I shall see or hear in the course of my profession, as well as outside my profession in my intercourse with men, if it be what should not be published abroad, I will never divulge, holding such things to be holy secrets.

Now if I carry out this oath, and break it not, may I gain for ever reputation among all men for my life and for my art; but if I break it and forswear myself, may the opposite befall me.[7] – Translation by W.H.S. Jones.

" First do no harm "

It is often said that the exact phrase "First do no harm" (Latin: Primum non nocere) is a part of the original Hippocratic oath. Although the phrase does not appear in the AD 245 version of the oath, similar intentions are vowed by, "I will abstain from all intentional wrong-doing and harm". The phrase "primum non nocere" is believed to date from the 17th century (see detailed discussion in the article on the phrase).

Another equivalent phrase is found in Epidemics, Book I, of the Hippocratic school: "Practice two things in your dealings with disease: either help or do not harm the patient".[8] The exact phrase is believed to have originated with the 19th-century English surgeon Thomas Inman.[9]

Context and interpretation

The oath is arguably the best known text of the Hippocratic Corpus, although most modern scholars do not attribute it to Hippocrates himself, estimating it to have been written in the fourth or fifth century BC.[10] Alternatively, classical scholar Ludwig Edelstein proposed that the oath was written by the Pythagoreans, an idea that others questioned for lack of evidence for a school of Pythagorean medicine.[11]

Its general ethical principles are also found in other works of the Corpus: the Physician mentions the obligation to keep the 'holy things' of medicine within the medical community (i.e. not to divulge secrets); it also mentions the special position of the doctor with regard to his patients, especially women and girls.[12] However, several aspects of the oath contradict patterns of practice established elsewhere in the Corpus. Most notable is its ban on the use of the knife, even for small procedures such as lithotomy, even though other works in the Corpus provide guidance on performing surgical procedures.[13]

Providing poisonous drugs would certainly have been viewed as immoral by contemporary physicians if it resulted in murder. However, the absolute ban described in the oath also forbids euthanasia. Several accounts of ancient physicians willingly assisting suicides have survived.[14] Multiple explanations for the prohibition of euthanasia in the oath have been proposed: it is possible that not all physicians swore the oath, or that the oath was seeking to prevent widely held concerns that physicians could be employed as political assassins.[15]

The interpreted 275 AD fragment of the oath contains a prohibition of abortion that is in contradiction to original Hippocratic text On the Nature of the Child, which contains a description of an abortion, without any implication that it was morally wrong,[16] and descriptions of abortifacient medications are numerous in the ancient medical literature.[17] While many Christian versions of the Hippocratic Oath, particularly from the middle-ages, explicitly prohibited abortion, the prohibition is often omitted from many oaths taken in US medical schools today, though it remains controversial.[18] Scribonius Largus was adamant in 43 AD (the earliest surviving reference to the oath) that it preclude abortion.[19]

As with Scribonius Largus, there seemed to be no question to Soranus that the Hippocratic Oath prohibits abortion, although apparently not all doctors adhered to it strictly in his time. According to Soranus' 1st or 2nd century AD work Gynaecology, one party of medical practitioners banished all abortives as required by the Hippocratic Oath; the other party—to which he belonged—was willing to prescribe abortions, but only for the sake of the mother's health.[19][20]

The oath stands out among comparable ancient texts on medical ethics and professionalism through its heavily religious tone, a factor which makes attributing its authorship to Hippocrates particularly difficult. Phrases such as 'but I will keep pure and holy both my life and my art' suggest a deep, almost monastic devotion to the art of medicine. He who keeps to the oath is promised 'reputation among all men for my life and for my art'. This contrasts heavily with Galenic writings on professional ethics, which employ a far more pragmatic approach, where good practice is defined as effective practice, without reference to deities.[21]

The oath's importance among the medical community is nonetheless attested by its appearance on the tombstones of physicians, and by the fourth century AD it had come to stand for the medical profession.[22]

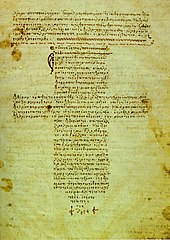

The oath continued to be in use in the Byzantine Christian world with its references to pagan deities replaced by a Christian preamble, as in the 12th-century manuscript pictured in the shape of a cross.[23]

Modern versions and relevance

The Hippocratic Oath has been eclipsed as a document of professional ethics by more extensive, regularly updated ethical codes issued by national medical associations, such as the AMA Code of Medical Ethics (first adopted in 1847), and the British General Medical Council's Good Medical Practice. These documents provide a comprehensive overview of the obligations and professional behaviour of a doctor to their patients and wider society. Doctors who violate these codes may be subjected to disciplinary proceedings, including the loss of their license to practice medicine. Nonetheless, the length of these documents has made their distillations into shorter oaths an attractive proposition. In light of this fact, several updates to the oath have been offered in modern times,[25][26] some facetious.[27]

The oath has been modified numerous times.

In the United States, the majority of osteopathic medical schools use the Osteopathic Oath in place of or in addition to the Hippocratic Oath. The Osteopathic Oath was first used in 1938, and the current version has been in use since 1954.[28]

One of the most significant revisions was first drafted in 1948 by the World Medical Association (WMA), called the Declaration of Geneva. "During the post World War II and immediately after its foundation, the WMA showed concern over the state of medical ethics in general and over the world. The WMA took up the responsibility for setting ethical guidelines for the world's physicians. It noted that in those years the custom of medical schools to administer an oath to its doctors upon graduation or receiving a license to practice medicine had fallen into disuse or become a mere formality".[29] In Germany during the Third Reich, medical students did not take the Hippocratic Oath, although they knew the ethic of "nil nocere" — do no harm.[30]

In the 1960s, the Hippocratic Oath was changed to require "utmost respect for human life from its beginning", making it a more secular obligation, not to be taken in the presence of God or any gods, but before only other people. When the oath was rewritten in 1964 by Louis Lasagna, Academic Dean of the School of Medicine at Tufts University, the prayer was omitted, and that version has been widely accepted and is still in use today by many US medical schools:[31]

I swear to fulfill, to the best of my ability and judgment, this covenant:

I will respect the hard-won scientific gains of those physicians in whose steps I walk, and gladly share such knowledge as is mine with those who are to follow.

I will apply, for the benefit of the sick, all measures [that] are required, avoiding those twin traps of overtreatment and therapeutic nihilism.

I will remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon's knife or the chemist's drug.

I will not be ashamed to say "I know not," nor will I fail to call in my colleagues when the skills of another are needed for a patient's recovery.

I will respect the privacy of my patients, for their problems are not disclosed to me that the world may know. Most especially must I tread with care in matters of life and death. If it is given me to save a life, all thanks. But it may also be within my power to take a life; this awesome responsibility must be faced with great humbleness and awareness of my own frailty. Above all, I must not play at God.

I will remember that I do not treat a fever chart, a cancerous growth, but a sick human being, whose illness may affect the person's family and economic stability. My responsibility includes these related problems, if I am to care adequately for the sick.

I will prevent disease whenever I can, for prevention is preferable to cure.

I will remember that I remain a member of society, with special obligations to all my fellow human beings, those sound of mind and body as well as the infirm.

If I do not violate this oath, may I enjoy life and art, respected while I live and remembered with affection thereafter. May I always act so as to preserve the finest traditions of my calling and may I long experience the joy of healing those who seek my help.

In a 1989 survey of 126 US medical schools, only three reported use of the original oath, while thirty-three used the Declaration of Geneva, sixty-seven used a modified Hippocratic Oath, four used the Oath of Maimonides, one used a covenant, eight used another oath, one used an unknown oath, and two did not use any kind of oath. Seven medical schools did not reply to the survey.[32]

As of 1993, only 14 percent of medical oaths prohibited euthanasia, and only 8 percent prohibited abortion.[33]

In a 2000 survey of US medical schools, all of the then extant medical schools administered some type of profession oath. Among schools of modern medicine, sixty-two of 122 used the Hippocratic Oath, or a modified version of it. The other sixty schools used the original or modified Declaration of Geneva, Oath of Maimonides, or an oath authored by students and or faculty. All nineteen osteopathic schools used the Osteopathic Oath.[34]

In France, it is common for new medical graduates to sign a written oath.[35][36]

In 1995, Sir Joseph Rotblat, in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize, suggested a Hippocratic Oath for Scientists.[37]

Breaking the Hippocratic Oath

There is no direct punishment for breaking the Hippocratic Oath, although an arguable equivalent in modern times is medical malpractice which carries a wide range of punishments, from legal action to civil penalties.[38] In the United States, several major judicial decisions have made reference to the classical Hippocratic Oath, either upholding or dismissing its bounds for medical ethics: Roe v. Wade, Washington v. Harper, Compassion in Dying v. State of Washington (1996), and Thorburn v. Department of Corrections (1998).[39] In antiquity, the punishment for breaking the Hippocratic oath could range from a penalty to losing the right to practice medicine.[40]

See also

- Ethical codes of conduct for physicians

- Ethical principles for human experimentation

- Ethical practices for engineers

References

- ^ Kantarjian, Hagop (15 October 2014). "Relevant of the Hippocratic Oath in the 21st Century".

- ^ Edelstein, Ludwig (1943). The Hippocratic Oath: Text, Translation and Interpretation. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-8018-0184-6.

- ^ Norman, Jeremy. "Perhaps the Earliest Surviving Text of the Hippocratic Oath". HistoryofInformation.com. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ^ "Codices urbinates graeci Bibliothecae Vaticanae: Folio 64(Urb.gr.64)". Vatican Library: DigiVatLib. 900–1100. p. folio:116 microfilm: 121.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ North, Michael (2002). "Greek Medicine: "I Swear by Apollo Physician...": Green Medicine from the Gods to Galen". National Institute of Health; National Library of Medicine; History of Medicine Division.

- ^ Wecheli, Andreae (1595). "Hippocrates. Τα ενρισκομενα Opera omnia". Frankfurt: National Institute of Health; National Library of Medicine; History of Medicine Division).

- ^ a b Hippocrates of Cos (1923). "The Oath". Loeb Classical Library. 147: 298–299. doi:10.4159/DLCL.hippocrates_cos-oath.1923. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ Lloyd, Geoffrey, ed. (1983). Hippocratic Writings (2nd ed.). London: Penguin Books. p. 94. ISBN 978-0140444513.

- ^ Sokol, Daniel K. (2013). "'First do no harm' revisited". BMJ. 347: f6426. doi:10.1136/bmj.f6426. PMID 24163087. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ Jouanna, Jacques (2001). Hippocrates. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801868184.

- ^ Temkin, Owsei (2002). "On second thought" and other essays in the history of medicine and science. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6774-3.

- ^ Potter, ed. and. transl. by Paul (1995). Hippocrates ([Reprint] ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Univ. Press u.a. pp. 295–315. ISBN 9780674995314.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - ^ Nutton, Vivian (2012). Ancient medicine (2nd ed.). Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 68. ISBN 978-0415520959.

- ^ Edelstein, Ludwig (1967). Ancient Medicine: Selected Papers of Ludwig Edelstein. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins Press. pp. 9–15. ISBN 9780801801839.

- ^ Markel, Howard. ""I Swear by Apollo" — On Taking the Hippocratic Oath" (PDF). www.nejm.org. Massachusetts Medical Society. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ Lonie, Iain M. (1981). The Hippocratic treatises, "On generation," "On the nature of the child," "Diseases IV" a commentary. Berlin: De Gruyter. p. 7. ISBN 9783110863963.

- ^ King, Helen (1998). Hippocrates' woman : reading the female body in ancient Greece. London: Routledge. pp. 132–156. ISBN 978-0415138956.

- ^ Markel, Howard (13 May 2004). ""I Swear by Apollo" — On Taking the Hippocratic Oath". New England Journal of Medicine. 350 (20): 2026–2029. doi:10.1056/NEJMp048092. PMID 15141039.

- ^ a b "Scribonius Largus"

- ^ Soranus, Owsei Temkin (1956). Soranus' Gynecology. I.19.60: JHU Press. ISBN 9780801843204. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Wear, Geyer-Kordesch, French (eds) (1993). Doctors and Ethics: The Earlier Historical Setting of Professional Ethics. Amsterdam: Rodopi. pp. 10–37.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ von Staden, H (1996). "In a pure and holy way. Personal and professional conduct in the Hippocratic Oath". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 51 (51): 404–437. doi:10.1093/jhmas/51.4.404.

- ^ Nutton, Vivian (2012). Ancient medicine (2nd ed.). Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 415, note 87. ISBN 978-0415520959.

- ^ National Library of Medicine 2006

- ^ Buchholz B, et al. Prohibición de la litotomía y derivación a expertos en los juramentos médicos de la genealogía hipocrática. Actas Urologicas Espanolas. Volume 40, Issue 10, December 2016, Pages 640–645.

- ^ Oswald, H.; Phelan, P. D.; Lanigan, A.; Hibbert, M.; Bowes, G.; Olinsky, A. (1994). "Outcome of childhood asthma in mid-adult life". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 309 (6947): 95–96. PMC 2540578. PMID 8038676.

- ^ Schiedermayer, D. L. (1986). "The Hippocratic Oath — Corporate Version". New England Journal of Medicine. 314 (1): 62. doi:10.1056/NEJM198601023140122. PMID 3940324.

- ^ "Osteopathic Oath". osteopathic.org. American Osteopathic Association. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ World Medical Association, Inc. "WMA History". www.wma.net. World Medical Association, Inc. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Baumslag, Naomi (2005). Murderous Medicine: Nazi Doctors, Human Experimentation, and Typhus. Praeger Publishers. pp. xxv. ISBN 9780275983123.

- ^ "The Hippocratic Oath Today".

- ^ Crawshaw, R (8 October 1994). "The Hippocratic oath. Is alive and well in North America". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 309 (6959): 952–953. doi:10.1136/bmj.309.6959.952. PMC 2541124. PMID 7950672.

- ^ Markel, Howard. ""I Swear by Apollo" — On Taking the Hippocratic Oath" (PDF). www.nejm.org. Massachusetts Medical Society. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ Kao, AC; Parsi, KP (September 2004). "Content analyses of oaths administered at U.S. medical schools in 2000". Academic Medicine. 79 (9): 882–7. doi:10.1097/00001888-200409000-00015. PMID 15326016.

- ^ Sritharan, Kaji; Georgina Russell; Zoe Fritz; Davina Wong; Matthew Rollin; Jake Dunning; Bruce Wayne; Philip Morgan; Catherine Sheehan (December 2000). "Medical oaths and declarations". BMJ. 323 (7327): 1440–1. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7327.1440. PMC 1121898. PMID 11751345.

- ^ Crawshaw, R; Pennington, T H; Pennington, C I; Reiss, H; Loudon, I (October 1994). "Letters". BMJ. 309 (6959): 952–953. doi:10.1136/bmj.309.6959.952. PMC 2541124. PMID 7950672.

- ^ "Nobel Prize winner calls for ethics oath". Physics World. 19 December 1997. Retrieved 2008-07-19.

- ^ Groner M.D., Johnathan (2008). "The Hippocratic Paradox: The Role of The Medical Profession In Capital Punishment In The United States". Fordham Urban Law.

- ^ Hasday, Lisa (23 February 2013). "The Hippocratic Oath as Literary Text: A Dialogue". Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law, and Ethics. 2 (2): Article 4. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ Nutton, Vivian (2004). Ancient Medicine. New York, NY: Routledge.

Further reading

- Hulkower, Raphael (2010). "The History of the Hippocratic Oath: Outdated, Inauthentic, and Yet Still Relevant". The Einstein Journal of Biology and Medicine. 25/26: 41–44.

- The Hippocratic Oath Today: Meaningless Relic or Invaluable Moral Guide? – a PBS NOVA online discussion with responses from doctors as well as 2 versions of the oath. pbs.org

- Kass, Leon (2008). Toward a More Natural Science. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0029170717.

- Lewis Richard Farnell, Greek Hero Cults and Ideas of Immortality, 1921.

- "Codes of Ethics: Some History" by Robert Baker, Union College in Perspectives on the Professions, Vol. 19, No. 1, Fall 1999, ethics.iit.edu

External links

- Hippocratic Oath, The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (h2g2).

- Hippocratic Oath – Classical version, pbs.org

- Hippocratic Oath – Modern version, pbs.org

- Hippocratis jusiurandum – Image of a 1595 copy of the Hippocratic oath with side-by-side original Greek and Latin translation, bium.univ-paris5.fr

- Hippocrates | The Oath – National Institutes of Health page about the Hippocratic oath, nlm.nih.gov

- Tishchenko P. D. Resurrection of the Hippocratic Oath in Russia, zpu-journal.ru

- AMA Code of Medical Ethics

- Good Medical Practice (from Britain's General Medical Council)