Thomas Palaiologos

| Thomas Palaiologos | |

|---|---|

| |

| Despot of the Morea | |

| Reign | 1428 – 12 May 1465 (in exile 1460–1465) |

| Predecessor | Theodore II Palaiologos (alone) |

| Successor | Andreas Palaiologos (titular) |

| Co-regent | Theodore II Palaiologos (1428–1443) Constantine Palaiologos (1428–1449) Demetrios Palaiologos (1449–1460) |

| Born | 1409 Constantinople |

| Died | 12 May 1465 (aged 55) Rome |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Catherine Zaccaria |

| Issue | Helena Zoe Andreas Manuel |

| Dynasty | Palaiologos |

| Father | Manuel II Palaiologos |

| Mother | Helena Dragaš |

| Religion | Catholic/Orthodox |

| Signature | |

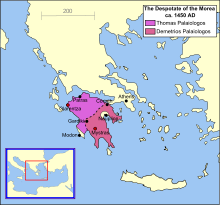

Thomas Palaiologos or Palaeologus (Greek: Θωμᾶς Παλαιολόγος; 1409 – 12 May 1465) was a younger brother of Constantine XI Palaiologos, the final Byzantine emperor, and served as Despot of the Morea from 1428 until the fall of the despotate in 1460 (though he continued to claim the title until his death five years later). Thomas was appointed as Despot of the Morea by his oldest brother, Emperor John VIII Palaiologos, in 1428, joining his two brothers and other despots Theodore and Constantine, already governing the Morea. Though Theodore proved reluctant to cooperate with his brothers, Thomas and Constantine successfully worked to strengthen the despotate and expand its borders. In 1432, Thomas brought the remaining territories of the Latin Principality of Achaea, established during the Fourth Crusade more than two hundred years earlier, into Byzantine hands by marrying Catherine Zaccaria, daughter and heir to the principality.

In 1449, Thomas supported the ascension of his brother Constantine, who then became Emperor Constantine XI, to the throne despite the machinations of his other brother, Demetrios, who himself desired the throne. After Constantine's rise to the throne, Demetrios was then assigned by Constantine to govern the Morea with Thomas but the two brothers found it difficult to cooperate, often quarreling with each other. In the aftermath of the Fall of Constantinople and end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II allowed Thomas and Demetrios to continue to rule as Ottoman vassals in the Morea. Thomas hoped to turn the small despotate into a rallying point of a campaign to restore the empire, hoping to gain support from the Papacy and Western Europe. Constant quarreling with Demetrios, who supported the Ottomans instead, eventually led to Mehmed invading and conquering the Morea in 1460.

Thomas and his family, including his wife Catherine and his three younger children Zoe, Andreas and Manuel, escaped into exile to the Venetian-held city of Methoni and then to Corfu, where Catherine and the children stayed. In the hopes of raising support for a crusade to restore his lands in the Morea, and possibly the Byzantine Empire itself, Thomas travelled to Rome, where he was received and provided for by Pope Pius II. His hopes of retaking the Morea never materialized and he died in Rome on 12 May 1465. After his death, his claims were inherited by his oldest son Andreas, who also attempted to rally support for a campaign to restore the fallen despotate and the Byzantine Empire.

Biography

Early life and appointment as despot

As the Byzantine Empire fell apart and fragmented over the course of the 14th century, the emperors of the Palaiologan dynasty came to feel that the only sure way to keep their remaining holdings intact was to grant them to their sons, receiving the title of despot, as appanages to defend and govern.[1] Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos (r. 1391–1425) had a total of six sons who survived infancy. Manuel's eldest surviving son, John, was raised to co-emperor and designated to succeed Manuel as sole emperor upon his death. The second eldest son, Theodore was designated as Despot of the Morea and the third eldest, Andronikos, was made Despot of Thessaloniki in 1408 at just eight years old. Manuel's younger sons; Constantine, Demetrios and Thomas (the youngest, born in 1409), were kept in Constantinople as there weren't many lands left to grant to them. The younger children; Theodore, Andronikos, Constantine, Demetrios and Thomas were frequently described as having the distinction of Porphyrogennetos ("born in the purple"; born in the imperial palace during the reign of their father), a distinction that does not appear to have been shared by the emperor-to-be John.[2]

Relations between the Palaiologos brothers were not always good. Though the young John and Constantine appears to have got on well with each other, relations between Constantine and the younger Demetrios and Thomas were not as friendly.[2] The complex relationships between the sons of Manuel II were put to the test when John, now Emperor John VIII, appointed Constantine as Despot of the Morea in 1428. Since his brother Theodore refused to step down from his role as despot, the despotate became governed by two members of the imperial family for the first time since its creation in 1349. Soon thereafter, the younger Thomas (aged 19) was also appointed as Despot of the Morea, meaning that the nominally undivided despotate had effectively disintegrated into three smaller principalities.[3]

Theodore did not make way for Constantine or Thomas in the despotate's capital, Mystras. Instead, Theodore granted Constantine lands throughout the Morea, including the northern harbor town of Aigio, fortresses and towns in Laconia (in the south), and Kalamata and Messenia in the west. Constantine made his capital as despot the town Glarentza. Meanwhile, Thomas was given lands in the north and based himself in the castle of Kalavryta.[3]

Despot under the Byzantine Empire

Shortly after being appointed as despots, Constantine and Thomas, together with Theodore, decided to join forces in an attempt to seize the flourishing and strategic port of Patras in the north-west of the Morea, then under the rule of its Catholic Archbishop. The campaign, unsuccessful (perhaps mainly due to Theodore being reluctant to partake and staying in Mystras), was Thomas's first experience of war.[3] Constantine captured Patras, then having been in foreign hands for 225 years, on his own a year later.[4]

Thomas's early tenure as Despot of the Morea was not without acquisitions either. For years, Thomas and Constantine had been eating away at the last remnants of the Principality of Achaea, a crusader state established during the Fourth Crusade in 1204 which had once governed almost the entire peninsula. It was Thomas who finally brought an end to the principality by marrying Catherine Zaccaria, daughter and heir of the final prince, Centurione II Zaccaria. With Centurione's death in 1432, Thomas could claim control over all of his remaining territories. By the 1430s, Thomas and Constantine had ensured that nearly the entire Peloponnese was once more in Byzantine hands for the first time since 1204, the only exception being the few port towns and cities held by the Republic of Venice.[5]

Murad II, Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, which occupied most of the Byzantine Empire's former territory and had relegated the empire and the despotate as effectively vassal states, felt uneasy about the recent string of Byzantine successes in the Morea. In 1431, Turahan Bey, a Turkish general who governed Thessaly, sent his troops south to demolish the Morea's primary defensive fortifications, the Hexamilion wall, in an effort to remind the despots that they were the Sultan's vassals.[6]

In March 1432, Constantine (who perhaps wished to be closer to Mystras) made a new territorial agreement, presumably approved by Theodore and John VIII, with Thomas. Thomas agreed to cede his fortress Kalavryta to Constantine, who made it his new capital, in exchange for Elis, which Thomas made his new capital.[6] Though relations between the three despots thus appears to have been good in 1432, they soon soured. John VIII had no sons to suceed him and it was thus assumed that his successor would be one of his four surviving brothers (Andronikos having died some time before). John VIII's preferred successor was Constantine and though this choice was accepted by Thomas, who by now got on well with his older brother, it was resented by the still older Theodore. When Constantine was summoned to the capital in 1435, Theodore believed this was to appoint Constantine as co-emperor and designated heir (which was not actually the case) and he too travelled to Constantinople to raise his objections. The quarrel between Constantine and Theodore was not resolved until the end of 1436, when the future Patriarch Gregory Mammas was sent to bring them to their senses and prevent civil war. When Constantine was summoned to act as regent in Constantinople while John VIII was away at the Council of Florence from 1437 to 1440, Theodore and Thomas stayed in the Morea.[7] In November 1443, Constantine gave over control of Selymbria, which he had received after helping to deal with the rebellion of their younger brother Demetrios, to Theodore, who in turn abandoned his position as Despot of the Morea, making Constantine and Thomas the sole Despots of the Morea. Though this brought Theodore closer to Constantinople, it also made Constantine the ruler of the capital of the Morea and one of the most powerful men in the small empire.[8] With Theodore and Demetrios out of their way, Constantine and Thomas hoped to strengthen the Morea, by now the cultural center of the Byzantine world, and make it a safe and nearly self-suffient principality.[9] The philosopher Gemistus Pletho advocated that while Constantinople was the New Rome, Mystras and the Morea could become the "New Sparta", a centralized and strong hellenic kingdom in its own right.[10]

Among the actions taken during the brothers' project of strengthening the despotate was to reconstruct the Hexamilion wall, destroyed by the Turks in 1431. Together, they completely restored the wall, being finished in March 1444.[11] The wall was destroyed by the Turks again in 1446 after Constantine had attempted to expand his control northwards and had refused the sultan's demands of dismantling the wall.[12] Constantine and Thomas were determined to hold the wall and had brought all their available forces, amounting to perhaps as many as twenty thousand men, to defend it.[13] Despite this, the battle by the wall in 1446 was an overwhelming Turkish victory, Constantine and Thomas barely escaping with their lives. Turahan Bey was sent south to take Mystras and devastate Constantine's lands while Sultan Murad II led his forces in the north of the Peloponnese.[12] Although Turahan failed to take Mystras, this was of little consequence as Murad did not wish to conquer the Morea at the time, merely to instill terror, and the Turks soon left the peninsula, devastated and depopulated.[14] Constantine and Thomas were in no position to ask for a truce and were forced to accept Murad as their lord and pay him tribute, promising to never again restore the Hexamilion wall.[15]

Their former co-despot Theodore died in June 1448, and on 31 October of the same year, Emperor John VIII passed away. The potential successors to the throne were Constantine, Demetrios and Thomas. John had not formally designated and heir, though everyone knew he favored Constantine and ultimately, the will of their mother, Helena Dragaš (who also preferred Constantine), prevailed.[16] Both Thomas, who had no intention of claiming the throne, and Demetrios, who most certainly did, hurried to Constantinople and reached the capital before Constantine. Though Demetrios was favored by many due to his anti-unionist sentiment, Helena reserved her right to act as regent until her eldest son, Constantine arrived, stalling Demetrios's attempt at seizing the throne. Thomas accepted Constantine's appointment and Demetrios, who soon thereafter joined in proclaiming Constantine as his new emperor, was overruled. Soon thereafter, Sphrantzes informed Sultan Murad II, who also accepted the ascension of Constantine, now Emperor Constantine XI.[17] In order to remove Demetrios from the capital and its vicinity, Constantine made Demetrios Despot of the Morea, to rule the despotate together with Thomas. Demetrios was granted Mystras and primarily ruled the southern and eastern parts of the despotate, with Thomas ruling Corinthia and the north-west, variously using Patras or Leontari as his capital.[18]

In 1451, Sultan Murad II, by then old and tired and having let go of all intentions of conquering Constantinople, died and was succeeded as sultan by his young and vigorous son Mehmed II,[19] who was determined above all else to take the city.[20] In 1452, during the preparation stages of the Ottoman siege of Constantinople, Constantine XI sent an urgent message to the Morea, requesting that one of his brothers bring their forces to help him defend the city. To prevent aid coming from the Morea, Mehmed II sent Turahan Bey to devastate the peninsula once more.[21] The Turkish attack was repelled by an army commanded by Matthaios Asan, brother-in-law of Demetrios, but this victory came too late to offer any aid to Constantinople.[22]

Continued rule in the Morea

Constantinople ultimately fell on 29 May 1453, Constantine XI dying in its defense, ending the Byzantine Empire. In the aftermath of Constantinople's fall, one of the most pressing threats to the new Ottoman regime was the possibility that one of Constantine XI's surviving relatives would find a following and return to reclaim the empire. Luckily for Mehmed II, the two despots in the Morea represented scarcely more than a nuisance and were allowed to keep their titles and lands. Although both Thomas and Demetrios might have considered making their small despotate the rallying point of a campaign to restore the empire, they were never able to cooperate and spent most of their resources fighting each other rather than preparing for a struggle against the Turks.[23]

Shortly after Constantinople fell, a revolt broke out against the despots in the Morea, prompted by the many Albanian immigrants to the region being unhappy with the actions of the local Greek landowners.[21] The Albanians had respected earlier despots, such as Constantine and Theodore, but despised the two current despots and without central authority from Constantinople, they saw their opportunity to gain control of the despotate for themselves. In Thomas's part of the despotate, the rebels chose to proclaim John Asen Zaccaria, bastard son of Thomas's father-in-law Centurione II, as their leader and in Demetrios's part of the despotate, the leader of the revolt was Manuel Kantakouzenos, grandson of Demetrios I Kantakouzenos (who had served as despot until 1384) and great-great-grandson of Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos (r. 1347–1354).[22] Mehmed II did not wish to see the despotate pass into the hands of Albanians, since he was the suzerain of the current despots, and sent an army to quell the rebellion in December 1453. The rebellion was not fully crushed until October 1454, when Turahan Bey arrived to aid the despots in firmly establishing their authority in the region. In return for the aid, Mehmed demanded a heavy tribute from Thomas and Demetrios.[21]

Neither brother could raise the sum demanded by the Sultan and they were divided in their policies. While Demetrios, probably the more realistic of the two, had given up hope of Christian aid from the west and thought it might be best to placate the Turks, Thomas retained hope that the Papacy might yet call for a crusade to restore the Byzantine Empire. With no money coming from the Morea, Mehmed eventually lost his patience with the Palaiologoi. The Ottoman army marched from Adrianople in May 1458 and entered the Morea, where the only real resistence was faced at Corinth, within the domain governed by Demetrios.[21] Leaving his artillery to bombard and besiege that city, Mehmed left with most of his army to devastate and conquer the northern parts of the despotate, under Thomas's jurisdiction. Corinth at last gave up in August, after several cities in the north had already surrendered, and Mehmed imposed a heavy retribution on the Morea. The territory under the two brothers was drastically reduced, Corinth, Patras and much of the north-west of the peninsula were annexed into the Ottoman Empire and provided with Turkish governors, with the Palaiologoi only being allowed to keep the south (including the despotate's nominal capital, Mystras), on the condition that they paid their annual tribute to the sultan.[24]

Almost as soon as Mehmed had left the Morea, the two brothers began quarreling with each other again. Demetrios invited Mehmed to return to the Morea and support his cause against Thomas, while Thomas sent pleas to the Papacy for aid. Neither brother had any true control over their remainig territory, where the Greek landowners mostly did as they pleased. Thomas's pleas to the west did represent a real threat to the Ottomans, a threat made even greater through the support of the plan by the vocal Cardinal Bessarion, a Byzantine refugee who had escaped the empire years earlier. Pope Pius II convened a council in 1459 in Mantua and sent Bessarion and some others to preach for a crusade against the Ottomans throughout Europe. Furthermore, Pius II had sent 300 soldiers to aid Thomas, who successfully retook Kalavryta from the Ottomans and attempted to retake Patras.[24] Soon after, the Papal troops lost interest and returned home and Thomas began to quarrel with Demetrios once more. Near the end of 1459, Mehmed ordered the Bishop of Lacedaemon to make the two swear to keep the peace, but this had little impact and they were once more quarreling a few weeks later.[25]

Determined to bring order to Greece, Mehmed decided that the destruction of the despotate and its full annexation directly into his empire was the only possible solution. The sultan assembled his army once more in April 1460 and led it in person first to Corinth and then on to Mystras. Demetrios surrendered to the Ottomans without a fight, fearing retribution and already having sent his family to safety in Monemvasia. Mystras thus fell into Ottoman hands on 29 May 1460, exactly seven years after Constantinople's fall. The few places in the Morea that dared resist the sultan's army were devastated as per Islamic law, the men being massacred and the women and children being taken away. As large numbers of Greek refugees escaped to Venetian-held territories such as Methoni and Koroni, the Morea was slowly subdued, the last resistence being led by Constantine Graitzas Palaiologos, a relative of Thomas and Demetrios, at Salmenikon in July 1461.[25]

Life in exile

By the time the despotate fell, Thomas had already fled to Methoni with his wife Catherine and his children Andreas, Manuel and Zoe. In July 1460, Thomas and his family, accompanied by other Greek nobles (such as the historian George Sphrantzes) fled to Corfu with Venetian help. Catherine and the children stayed in Corfu, but Thomas chose to travel to Rome in November that same year, hopeful of convincing Pope Pius II to call for a crusade.[26] Thomas, as the brother of the final Byzantine emperor, was the highest profile ruler in exile of all the many Christians who escaped the Balkans over the course of the Ottoman conquest.[27]

Upon arriving in Rome, Thomas met with Pius II, who bestowed him with the Golden Rose, lodging in the Ospedale di Santo Spirito in Sassia and a pension of 300 ducats each month (for a total of 3600 annually). In addition to the papal pension, Thomas also received an additional 200 ducats a month from the cardinals and 500 ducats from the Republic of Venice, which also begged him not to return to Corfu as to not affect Venice's already tenuous relations with the Ottomans. Thomas's many followers considered the money provided to him to be barely enough to support the despot, and certainly nowhere near enough to also support themselves.[28] The Papacy recognized Thomas as the rightful Despot of the Morea and the true heir to the Byzantine Empire, though Thomas never claimed the imperial title.[29]

On 12 April 1462, Thomas gave the supposed skull of Saint Andrew the Apostle, a precious relic which had been in Byzantine hands for centuries, to Pius II. Pius received the skull from Cardinal Bessarion at the Ponte Milvio. The ceremony, which was hailed as a return of Andrew to his relatives, the Romans (as symbolic descendants of Saint Peter) is depicted on Pius II's grave.[28]

During his stay in Rome, Thomas, on account of his "tall and handsome appearance", served as the model of the statue of Saint Paul which to this day stands in front of the St. Peter's Basilica.[28]

While many of the Balkan exiles were happy to live out their lives in obscurity,[27] Thomas hoped to eventually restore control over Byzantine territory. There were genuine preparations being conducted for a crusade, aimed at recovering Constantinople, during the 1460s, a plan staunchly supported by Thomas. To drum up support for the venture, Thomas toured Italy, carrying with him papal letters of indulgence. On his visits to the courts of the various landholders in Italy, Thomas presented himself as "a prince who was born to the illustrious and ancient family of the Palaiologoi ... a man who is now an immigrant, naked, robbed of everything except his lineage".[29]

Upon the death of his wife in August 1462,[30] Thomas summoned his children (who still remained at Corfu) to Rome, but they only arrived in the city after Thomas had died on 12 May 1465.[31] Though Thomas had been largely bypassed and forgotten by the Roman elite after Pius II's death in 1464,[29] he was buried with honor in the St. Peter's Basilica,[28][31] where his grave would survive the destruction and removal of the tombs of the Palaiologan emperors in Constantinople during the early years of Ottoman rule.[32] Modern efforts to locate his grave within the Basilica have so far proven fruitless.[28]

Children and descendants

It is generally accepted that Thomas had four children with Catherine Zaccaria.[26] These four children were:[33][34]

- Helena Palaiologina (1431 – 7 November 1473), the older of the couple's two daughters, Helena was married to Lazar Branković, a son of Đurađ Branković, Despot of Serbia. By the time of the Morea's fall, Helena had long since moved to Smederevo with her husband (who eventually became the Despot of Serbia in 1456). Lazar died in 1458 and Helena was left to care for the couple's three daughters. In 1459, Mehmed II invaded Serbia and put an end to the despotate, but Helena was allowed to leave the country. After spending some time in Ragusa, she moved to Corfu and lived there with her mother and siblings. After that, Helena became a nun and lived on the island of Lefkada, where she died in November 1473. Though Helena had many descendants through her three daughters Jelena, Milica and Jerina Brankovic, none of them carried on the Palaiologos name.[30]

- Zoe Palaiologina (c. 1449 – 7 April 1503), the younger daughter of Thomas and Catherine, Zoe was married off to Ivan III, Grand Prince of Moscow, by Pope Sixtus IV in 1472, in the hope of converting the Russians to Roman Catholicism. The Russians did not convert, with the marriage being celebrated according to Eastern Orthodox tradition. Zoe was called "Sophia" in Russia and her marriage to Ivan III served to strengthen Moscow's claim to be "Third Rome", the ideological and spiritual successor to the Byzantine Empire. Zoe and Ivan III had several children, who in turn had numerous descendants and though none carried the Palaiologos name, many of them used the double-headed eagle iconography of Byzantium. The famous Ivan the Terrible, Russia's first Tsar, was Sophia's grandson.[30]

- Andreas Palaiologos (17 January 1453 – June 1502), the older of the couple's two sons and the third child overall, Andreas lived most of his life in Rome, surviving on a gradually declining papal pension. After Thomas's death, Andreas was recognized by the Papacy and others in Italy as the rightful heir to the Despotate of the Morea and he would later go on to claim the title Imperator Constantinopolitanus ("Emperor of Constantinople") as well, hoping to one day restore the fallen Byzantine Empire. He attempted to organize an expedition to restore the empire in 1481, but his plans failed and he later ceded the rights to the imperial title to Charles VIII of France, hoping to use him as a champion against the Turks. Andreas died poor in Rome, whether or not he had any children is uncertain. His will specified that his titles were to be granted to the Catholic Monarchs in Spain (though they never used them).[35][36]

- Manuel Palaiologos (2 January 1455 – before 1512), the youngest of the four children, Manuel lived in Rome and lived off Papal money, much the same as his brother. As the pension deteriorated and Manuel (as second-in-line) did not have any titles to sell, he instead travelled Europe in search of someone to hire him in a military capacity. Failing to find satisfactory offers, Manuel surprised everyone else involved by travelling to Constantinople in 1476 and throwing himself on the mercy of Sultan Mehmed II, who graciously received him. He married an unknown woman and stayed in Constantinople for the rest of his life. Manuel had two sons, one of which died young and another which converted to Islam and whose eventual fate is uncertain.[30][34]

In the late 16th century, a family with the last name Paleologus, living in Pesaro in Italy, claimed descent from Thomas through a supposed third son, called John. This family later mainly lived in Cornwall and contained figures such as Theodore Paleologus, who worked as a soldier and hired assassin, and Ferdinand Paleologus, who retired in Barbados in the late 17th century.[37] The existence of a son of Thomas called John can't be proven with any certainty as no mention is made of a son by that name in contemporary records. It is possible that John was a real historical figure, possibly a illegitimate son of Thomas, or perhaps his grandson through of either of his known sons, Andreas or Manuel.[38]

See also

References

- ^ Nicol 1992, p. 3.

- ^ a b Nicol 1992, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Nicol 1992, p. 9.

- ^ Nicol 1992, p. 11.

- ^ Nicol 1992, p. 12.

- ^ a b Nicol 1992, p. 13.

- ^ Nicol 1992, p. 14.

- ^ Nicol 1992, p. 19.

- ^ Nicol 1992, p. 21.

- ^ Nicol 1992, p. 22.

- ^ Nicol 1992, p. 24.

- ^ a b Nicol 1992, p. 31.

- ^ Runciman 2009, p. 76.

- ^ Nicol 1992, p. 32.

- ^ Nicol 1992, p. 33.

- ^ Nicol 1992, p. 35.

- ^ Nicol 1992, p. 36.

- ^ Gilliland Wright 2013, p. 63.

- ^ Nicol 1992, p. 44.

- ^ Runciman 2009, p. 78.

- ^ a b c d Nicol 1992, p. 111.

- ^ a b Runciman 2009, p. 79.

- ^ Nicol 1992, p. 110.

- ^ a b Nicol 1992, p. 112.

- ^ a b Nicol 1992, p. 113.

- ^ a b Nicol 1992, p. 114.

- ^ a b Harris 2013, p. 649.

- ^ a b c d e Miller 1921, p. 500.

- ^ a b c Harris 2013, p. 650.

- ^ a b c d Nicol 1992, p. 115.

- ^ a b Harris 1995, p. 554.

- ^ Melvani 2018, p. 260.

- ^ Nicol 1992, pp. 114–116.

- ^ a b Harris 1995, p. 539.

- ^ Nicol 1992, p. 116.

- ^ Harris 1995, p. 537–554.

- ^ Nicol 1974, p. 179–203.

- ^ Hall 2015, p. 229.

Cited bibliography

- Gilliland Wright, Diana (2013). "The Fair of Agios Demetrios of 26 October 1449: Byzantine-Venetian relations and Land Issues in Mid-Century". Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 37 (1): 63–80.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Hall, John (2015). An Elizabethan Assassin: Theodore Paleologus: Seducer, Spy and Killer. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0750962612.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Harris, Jonathan (1995). "A Worthless Prince? Andreas Palaeologus in Rome, 1465-1502". Orientalia Christiana Periodica. 61: 537–554.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Harris, Jonathan (2013). "Despots, Emperors, and Balkan Identity in Exile". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 44 (3): 643–661.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Melvani, Nicholas (2018). "The tombs of the Palaiologan emperors". Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 42 (2): 237–260.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Miller, William (1921). "Miscellanea from the Near East: Balkan Exiles in Rome". Essays on the Latin Orient. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 457893641.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Nicol, Donald M. (1974). "Byzantium and England". Balkan Studies. 15 (2): 179–203.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Nicol, Donald M. (1992). The Immortal Emperor: The Life and Legend of Constantine Palaiologos, Last Emperor of the Romans. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0511583698.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Runciman, Steven (2009) [1980]. Lost Capital of Byzantium: The History of Mistra and the Peloponnese. New York: Tauris Parke Paperbacks. ISBN 978-1845118952.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

- 1409 births

- 1465 deaths

- Despots of the Morea

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from Eastern Orthodoxy

- Greek Roman Catholics

- Former Greek Orthodox Christians

- Palaiologos dynasty

- 15th-century Byzantine emperors

- 15th-century Despots of the Morea

- Porphyrogennetoi

- Byzantine people of the Byzantine–Ottoman wars

- Byzantine pretenders

- Burials at St. Peter's Basilica