Battle of Inchon

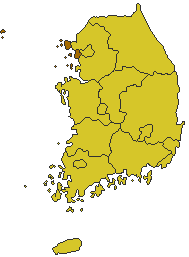

Template:Battlebox The Battle of Inchon (codename: "Operation Chromite") was a decisive 15-day invasion and battle during the Korean War. The battle began on September 15, 1950, and ended around September 28. During the amphibious operation, U.S. Marines under the command of General Douglas MacArthur secured Inchon and broke North Korean control of the Pusan region through a series of landings in enemy territory. The Battle of Inchon ended a string of victories by the invading North Korean People's Army (NKPA) and began a counterattack by United Nations forces that led to the recapture of Seoul. The northern advance ended when China's People's Liberation Army entered the conflict in support of North Korea, and defeated UN forces at the Battle of Chosin Reservoir.

Planning

The idea to land UN forces at Inchon was suggested by MacArthur after he visited the Korean battlefield on June 29, 1950, four days after the war began. MacArthur thought that the North Korean army would push the South Korean army back far past Seoul. He decided that the battered, demoralized, and under-equipped South Koreans couldn't hold off the NKPA's advances even with American reinforcements. MacArthur felt that he could turn the tide if he made a decisive troop movement behind enemy lines. He hoped that a move near Inchon would allow him to recapture Seoul, the capital and a vital supply point.

MacArthur decided to use the Joint Strategic and Operations Group (JSPOG) of his Far East Command (FECOM). The initial plan was met with skepticism by the other generals because Inchon's natural and artificial defenses were formidable. The approaches to Inchon are two restricted passages, Flying Fish and Eastern channels, which could be easily blocked by mines. The current of the channels was also dangerously quick — three to eight knots. The anchorage was small and the harbor was surrounded by tall seawalls. Commander Arlie G. Capps noted "We drew up a list of every natural and geographic handicap — and Inchon had 'em all."

These problems forced MacArthur to abandon his first plan, Operation Blueheart, which called for an Inchon landing in July 1950.

Despite these obstacles, in September MacArthur issued a revised plan of assault on Inchon: Plan 100-B, codenamed 'Operation Chromite'. A briefing lead by Admiral James Doyle concluded "the best that I can say is that Inchon is not impossible." Officers at the briefing spent much of their time asking about alternative landing sites such as Kunsan. MacArthur spent 45 minutes after the briefing explaining his reasons for choosing Inchon. He said that because Inchon was heavily defended the enemy wouldn't expect an attack there and that victory in Inchon would avoid a brutal winter campaign. General Forrest P. Sherman and Admiral J. Lawton Collins returned to Washington, D.C. and had the invasion approved.

Before the landing

One week before the main attack on Inchon, a joint Central Intelligence Agency-military intelligence reconnaissance operation codenamed Trudy Jackson placed a team of guerillas in Inchon. The group, led by Navy Lieutenant Eugene Clark, landed at Yonghung-do, an island in the mouth of the harbor. There they relayed back to U.S. forces.

With the help of natives, the guerillas gathered information about tides, mudflats, seawalls and enemy fortifications. The mission's most important contribution was the restarting of a lighthouse on Palmi-do. When the North Koreans discovered that the Allied agents had entered the peninsula, they sent an attack craft with 16 infantrymen. Eugene Clark mounted a machine gun on a sampan and sunk the attack boat. In response the North Koreans killed up to 50 civilians who helped Eugene Clark. For his actions Clark later received the Silver Star and the Legion of Merit.

As the landing groups neared, cruisers and destroyers shelled Wolmi-do and checked for mines in the Flying Fish Channel. The first Canadian forces entered the Korean War when the HMCS Cayuga, HMCS Athabaskan and HMCS Sioux bombarded the coast. The Fast Carrier Force flew fighter cover, interdiction, and ground attack missions. The intensified period of attacks tipped the North Koreans off that a landing may be imminent. The North Korean officer at Wolmi-do assured his superiors that he would throw the enemy back into the sea.

The Landing

Green Beach

Executed at 6:30 p.m. local time on September 15, 1950, the lead elements of U.S. X Corps hit Green Beach on the northern side of Wolmi-Do island. The landing force consisted of the 3rd Battalion and nine M26 Pershing tanks from the 1st Tank Battalion. One tank was equipped with a flamethrower (flame tank) and two others had bulldozer blades. The battle group landed in tank landing ships (LSTs, for "landing ship, tank") designed and built during World War II. The entire island was captured by noon at cost of less than 20 casualties. The attack killed over 200 North Koreans and captured 136 more. The prisoners of war were herded into a dry swimming pool for containment. The forces on Green Beach had to wait until 7:50 p.m. local time for the tides to rise and allow another group to land. During this time an extensive shelling and bombing campaign along with anti-tank mines placed on the only bridge kept the North Koreans from launching a significant counterattack. The second wave came from landings at Red Beach and Blue Beach.

The North Korean army had not been expecting an invasion at Inchon. After the storming of Green Beach they thought, probably because of American counter-intelligence, that the main invasion would happen at Kunsan. As a result, only a small force was diverted to Inchon. Those forces though were too late, they arrived after the UN forces had taken the Blue and Red Beaches. The troops already stationed at Inchon had been weakened by Clark's guerillas and napalm bombing runs had destroyed key ammo dumps.

Red Beach

The Red Beach forces, made up of the Fifth Marine Regimental Combat Team, used ladders to scale the sea walls. After neutralizing North Korean defenses they opened the causeway to Wolmi-Do, allowing the tanks from Green Beach to enter the battle. Red Beach forces suffered 8 dead and 28 wounded.

Blue Beach

The First Marine Regiment landing at Blue Beach was significantly south of the other two beaches and they reached shore last. As they approached the coast several NKPA gun emplacements sunk one LST. Destroyer fire and bombing runs silenced the North Korean defenses. When they finally arrived the North Korean forces at Inchon had already surrendered and so the Blue Beach forces suffered few casualties and little opposition. The First Marine Regiment spent much of its time strengthening the beachhead and preparing for the inland invasion.

Aftermath

Beachhead

Immediately after the North Korean resistance was put out in Inchon, the supply and reinforcement process began. Seabees and underwater demolitions teams that had arrived with the U.S. Marines constructed a pontoon dock on Green Beach and cleared debris from the water. The pontoon dock was then used to unload the remainder of the LSTs.

On September 16, the North Koreans, realizing their blunder, sent six columns of T-34 tanks to the beachhead. In response, two flights from the F4U Corsair squadron VMF-214 bombed the attackers. Despite the loss of one of the two planes, the air strike damaged or destroyed half of the tank column. A quick counter-attack by M26 Pershing tanks destroyed the remainder of the North Korean armored division and cleared the way for the capture of Inchon.

On September 19, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers repaired the local railroad up to eight miles (13km) inland. The Kimpo airstrip was captured and transport planes flew in gasoline and ordnance for the aircraft stationed at Inchon. The Marines continued unloading supplies and reinforcements. By September 22, they had unloaded 6,629 vehicles and 53,882 troops, along with 25,512 tons (23,000 tonnes) of supplies.

Ground war

In contrast to the quick victory at Inchon, the march to Seoul was slow and bloody. The NKPA launched another T-34 attack, which was trapped and destroyed, and launched a Yak bombing run in Inchon harbor, which did little damage. The North Koreans were trying to stall the UN offensive to give them more time to reinforce Seoul. MacArthur personally oversaw the 1st Marine Regiment as it fought through North Korean positions on the road to Seoul. At this point, supreme control over of Operation Chromite was given to Major General Edward Almond, the X Corps commander. It was Almond's goal to take Seoul on September 25, exactly three months after the war had began. On September 22, Marines entered Seoul to find a heavily fortified enemy, beginning a siege. Casualties mounted as the forces engaged in house-to-house guerilla warfare. On September 25, Almond declared Seoul liberated despite the fact that gunfire and artillery could still be heard in the northern suburbs.

On September 28, the North Koreans finally surrended. The last remnants of North Koreans in South Korea were defeated when Walker's 8th Army joined the X Corps and attacked the forces at Pusan. Of the 70,000 NKPA troops in Pusan, more than half were killed or captured. The remaining 30,000 soldiers retreated across the 38th parallel, exhausted and demoralized. The Allied assault continued north until the People's Republic of China sent troops into the war.

Sources

- "The Inchon Invasion, September 1950—Overview and Selected Images." U.S. Department of the Navy/Naval Historical Center. [1]

- Assault from the Sea: The Amphibious Landing at Inchon. U.S. Department of the Navy/Naval Historical Center. [2]

- Ballard, John R. "Operation Chromite: Counterattack at Inchon." Joint Forces Quarterly: Spring/Summer 2001. PDF file

- Montross, Lynn. "The Inchon Landing—Victory over Time and Tide." The Marine Corps Gazette. July 1951. [3]

- "The Landing at Inchon." Canadians in Korea: Valour Remembered. Veterans Affairs Canada. [4]