Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit

Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit | |

|---|---|

| Born | 24 May 1686 |

| Died | 16 September 1736 |

| Citizenship | German-Prussian (Assumed by A. Staruszkiewicz Polish[1]) |

| Known for | Fahrenheit temperature scale |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit[2] (24 May 1686 – 16 September 1736) was a German[3] physicist and engineer who worked most of his life in the Dutch Republic. The Fahrenheit (°F) temperature scale is named after him.

Biography

Fahrenheit was born in 1686 in DanzigPrussia [4] [5]. (since 1945 Communist take-over Gdansk, Poland). The Fahrenheits were a merchant family who had moved from one Hanseatic League city to others, Fahrenheit's great-grandfather had lived in Rostock and moved to Königsberg, and research suggests that the Fahrenheit family originated in Hildesheim.[4] Daniel's grandfather moved from Kneiphof (in Königsberg) to Danzig and settled there as a Hansa merchant in 1650. By widespread trading, he became the richest man in eastern Prussia.[5] His son, Daniel Fahrenheit (the father of the subject of this article), married Concordia (widowed name, Runge), daughter of the well-known Danzig business family of Schumann. Daniel Gabriel was the eldest of the five Fahrenheit children (two sons, three daughters) who survived childhood. His father ran businesses in Danzig and in Holland together with Ulrich Isenhut.

Pastor Bertling from Marienkirche in Danzig (St. Mary's Church, Danzig) reported, that Fahrenheit was baptized there on June 4, 1686, but that he became a Mennonite later on.

His parents died in 1702 from accidentally having eaten poisonous mushrooms. The inheritance records of Danzig reports Ein Erbe in der Hundegasse descend.gelegen mit der Mure de dit Eure scheidet von... Vormuendern des sel. Daniel Fahrenheit 5 unmuendige Kindern Daniel Gabriel, Ephraim, Anna Cordelia, Constantia, Virginia Elisabeth und zwar mit Consens usw von itzt gedachten ires Vaters Nahmen ab und the officials Johann Ernst Sayler, Machthaber Caspar David Schamm auch in dessen Abwesenheit zu.

Sixteen-year-old Gabriel Daniel Fahrenheit, the oldest of the five underage children, had to start working and began training as bookkeeper according to the Danzig Schoeppenburch, he then trained as a merchant in Amsterdam with Henning von Beumingen. However, his interest in natural science caused him to take up studies and experimentation in that field. From 1707 onwards, he made the obligatory journeyman's tour to obtain knowledge needed from glasblowers in Berlin, Halle, Leipzig, Dresden, Kopenhagen, and also to his hometown, where his brother remained. Fahrenheit sold his instruments to Island, Lappland and many other places. Fahrenheit met or was in contact with Ole Rømer, with whom he observed together the severe cold in Danzig in 1709. He went to Livonia and 1712-1714 back to Danzig, where he joined the Professor of Mathematics, Paul Pater at the Academic Gymnasium Danzig. He met with Christian Wolff, and Gottfried Leibniz.

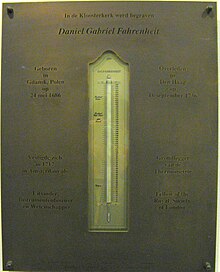

In 1717, Fahrenheit settled in The Hague with the trade of glassblowing, making barometers, altimeters, and thermometers. From 1718 onwards, he gave lectures in chemistry in Amsterdam. In 1724, he visited England and became a member of the Royal Society. (On this occasion, he is assumed to have signed himself as "Polonus", indicating that he was born a Polish subject.[6]) Fahrenheit died in The Hague and was buried there at the Kloosterkerk (Cloister Church).

Fahrenheit scale

According to Fahrenheit's 1724 article,[7] he determined his scale by reference to three fixed points of temperature. The lowest temperature was achieved by preparing a frigorific mixture of ice, water, and ammonium chloride, a salt, and waiting for it to reach equilibrium. The alcohol or mercury thermometer was placed into the mixture and the liquid in the thermometer allowed to descend to its lowest point. The reading on the thermometer was taken as 0 °F. The second reference point was selected as the reading of the thermometer when it was placed in still water as ice is just forming on the surface.[8] This was taken as 32 °F. The third calibration point, taken as 96 °F, was selected as the thermometer's reading when the instrument was placed under the arm or in the mouth.

Fahrenheit noted that mercury boils around 600 degrees on this temperature scale. Work by others showed that water boils about 180 degrees above its freezing point. The Fahrenheit scale later was redefined to make the freezing-to-boiling interval exactly 180 degrees.[7] It is because of the scale's redefinition that normal body temperature today is taken as 98.6 degrees, whereas it was 96 degrees on Fahrenheit's original scale.[9]

Until the switch to the Celsius scale, the Fahrenheit one was widely used in Europe. It is still used for everyday temperature measurements by the general population in the United States and, less so, in the UK.[10]

References

- ^ Staruszkiewicz, Andrzej. "Article (in Polish)" (PDF).

- ^ He signed as D. G. Fahrenheit in a 1736 letter

- ^ "Fahrenheit, Gabriel Daniel 1686 – 1736". The American Heritage Science Dictionary. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. 2005. Retrieved 2008-06-14.

- ^ Kant, Horst (1984). G. D. Fahrenheit / R. -A. F. de Réaumur / A. Celsius. B. G. Teubner. Retrieved 2008-06-14.

- ^ Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB), vol. 4, Berlin 1959, p. 746 [1]

- ^ Staruszkiewicz, Andrzej. "Article (in Polish)" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Fahrenheit temperature scale". Sizes, Inc. 2006-12-10. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ Heath, Jonathan. "Why does the Fahrenheit scale use 32 degrees as a freezing point?". PhysLink. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ Elert, Glenn (2002), "Temperature of a Healthy Human (Body Temperature)", Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 16: 122, doi:10.1046/j.1471-6712.2002.00069.x, retrieved 04-12-2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ For an early attempt to replace the Fahrenheit scale in the United States, see Johnson, Albert (1916). Abolish the Fahrenheit Thermometer. Washington, DC.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

- Bolton, Henry Carrington (1900). Evolution of the Thermometer, 1592-1743. Easton, Pennsylvania: The Chemical Publishing Company. pp. 66–79.

- Fahrenheit, D. G. (1724). "Experimenta circa gradum caloris liquorum nonnullorum ebullientium instituta (Experiments done on the degree of heat of a few boiling liquids)". Philosophical Transactions (London). 33: 1.

- Fahrenheit, D. G. (1724). "Experimenta et Observationes de Congelatione aquae in vacuo factae". Philosophical Transactions (London). 33: 78. doi:10.1098/rstl.1724.0016.

- Klemm, Friedrich (1959), "Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 4, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 746–747

- Kops, J (1976), "Who was G.D. Fahrenheit?", Zdravotnická pracovnice, vol. 26, no. 2 (published 1976 Feb), pp. 118–9, PMID:775856

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|publication-date=(help) (Czech)

- Lommel (1877), "Gabriel Daniel Fahrenheit", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 6, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, p. 535

- References: Altpreussische Monatsschrift, Verein fuer Geschichte Ost-und Westpreussen, Prof. Albert Momber

- Middleton, W. E. Knowles (1966). A History of the Thermometer and its Use in Meteorology. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins Press.

- Sorokina, T S (1986), "Creators of medical thermometry (on the 300th anniversary of the birth of Gabriel Daniel Fahrenheit--24 May 1686 and on the 350th anniversary of the death of Santorio Santorio--22 February 1636)", Klinicheskaia meditsina, vol. 64, no. 10 (published 1986 Oct), pp. 147–51, PMID:3543477

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|publication-date=(help) (Russian)

- Van Der Star, P., ed. (1984), Fahrenheit's Letters to Leibniz and Boerhaave, Editions Rodopi

External links

- Template:PND

- Letter from Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (scan) to Carl Linnaeus, 7 May 1736 n.s., [6] Template:De icon

- Senese, Fred (2005). "Why isn't 0°F the lowest possible temperature for a salt/ice/water mixture?".

Template:Persondata

{{subst:#if:Fahrenheit, Gabriel|}}

[[Category:{{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1686}}

|| UNKNOWN | MISSING = Year of birth missing {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1736}}||LIVING=(living people)}}

| #default = 1686 births

}}]] {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1736}}

|| LIVING = | MISSING = | UNKNOWN = | #default =

}}