Library catalog: Difference between revisions

rmv unreferenced opinion |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

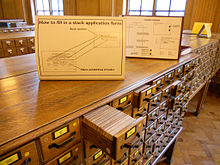

[[Image:Yale card catalog.jpg|thumb|The card catalog at [[Yale University]]'s [[Sterling Memorial Library]] .]] |

[[Image:Yale card catalog.jpg|thumb|The card |

||

catalog at [[Yale University]]'s [[Sterling Memorial Library]] .]] |

|||

[[Image:SML-Card-Catalog.jpg|thumb|Another view of the SML card catalog]] |

[[Image:SML-Card-Catalog.jpg|thumb|Another view of the SML card |

||

catalog]] |

|||

[[File:2010 Manchester UK 4467481691.jpg|thumb|The card catalogue in [[Manchester Central Library]]]] |

[[File:2010 Manchester UK 4467481691.jpg|thumb|The card catalogue in |

||

[[Manchester Central Library]]]] |

|||

A '''library catalog''' (or '''library catalogue''') is a register of all [[bibliography|bibliographic]] items found in a [[library]] or group |

A '''library catalog''' (or '''library catalogue''') is a register of |

||

all [[bibliography|bibliographic]] items found in a [[library]] or group |

|||

of libraries, such as a network of libraries at several locations. A |

|||

bibliographic item can be any information entity (e.g., books, computer |

|||

files, graphics, [[realia (library science)|realia]], cartographic |

|||

materials, etc.) that is considered library material (e.g., a single |

|||

[[novel]] in an [[anthology]]), or a group of library materials (e.g., a |

|||

[[trilogy]]), or linked from the catalog (e.g., a webpage) as far as it |

|||

is relevant to the catalog and to the users (patrons) of the library. |

|||

The '''card catalog''' was a familiar sight to library users for |

|||

The '''card catalog''' was a familiar sight to library users for generations, but it has been effectively replaced by the [[online public access catalog]] (OPAC). Some still refer to the online catalog as a "card catalog". Some libraries with OPAC access still have card catalogs on site, but these are now strictly a secondary resource and are seldom updated. Many of the libraries that have retained their physical card catalog post a sign advising the last year that the card catalog was updated. Some libraries have eliminated their card catalog in favour of the OPAC for the purpose of saving space for other use, such as additional shelving. |

|||

generations, but it has been effectively replaced by the [[online public |

|||

access catalog]] (OPAC). Some still refer to the online catalog as a |

|||

"card catalog". Some libraries with OPAC access still have card |

|||

catalogs on site, but these are now strictly a secondary resource and |

|||

are seldom updated. Many of the libraries that have retained their |

|||

physical card catalog post a sign advising the last year that the card |

|||

catalog was updated. Some libraries have eliminated their card catalog |

|||

in favour of the OPAC for the purpose of saving space for other use, |

|||

such as additional shelving. |

|||

== Goal == |

== Goal == |

||

[[Charles Ammi Cutter]] made the first explicit statement regarding the objectives of a bibliographic system in his [http://books.google.com/books?id=rj-f4-Ps-AkC&printsec=frontcover ''Rules for a Printed Dictionary Catalog''] in 1876. According to Cutter, those objectives were |

[[Charles Ammi Cutter]] made the first explicit statement regarding the |

||

objectives of a bibliographic system in his |

|||

[http://books.google.com/books?id=rj-f4-Ps-AkC&printsec=frontcover |

|||

''Rules for a Printed Dictionary Catalog''] in 1876. According to |

|||

Cutter, those objectives were |

|||

1. to enable a person to find a book of which either (Identifying objective) |

1. to enable a person to find a book of which either (Identifying |

||

objective) |

|||

*the author |

*the author |

||

| Line 29: | Line 54: | ||

*as to its character (literary or topical) |

*as to its character (literary or topical) |

||

These objectives can still be recognized in |

|||

These objectives can still be recognized in [http://www.allegro-c.de/formate/gz-1e.htm more modern definitions] formulated throughout the 20th century. 1960/61 Cutter's objectives were revised by Lubetzky and the Conference on Cataloging Principles (CCP) in Paris. The latest attempt to describe a library catalog's goals and functions was made in 1998 with [[Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records]] (FRBR) which defines four user tasks: find, identify, select, and obtain. |

|||

[http://www.allegro-c.de/formate/gz-1e.htm more modern definitions] |

|||

formulated throughout the 20th century. 1960/61 Cutter's objectives were |

|||

revised by Lubetzky and the Conference on Cataloging Principles (CCP) |

|||

in Paris. The latest attempt to describe a library catalog's goals and |

|||

functions was made in 1998 with [[Functional Requirements for |

|||

Bibliographic Records]] (FRBR) which defines four user tasks: find, |

|||

identify, select, and obtain. |

|||

== Catalog card == |

== Catalog card == |

||

| Line 41: | Line 73: | ||

xvi, 367p. : ill. ; 22 cm. |

xvi, 367p. : ill. ; 22 cm. |

||

Includes index. |

Includes index. |

||

ISBN 969-8612-02-8{{Please check ISBN|reason=Check digit (8) does not correspond to calculated 5.}} |

ISBN 969-8612-02-8{{Please check ISBN|reason=Check digit |

||

(8) does not correspond to calculated 5.}} |

|||

== Types == |

== Types == |

||

== History == |

== History == |

||

[[Image:Schlagwortkatalog.jpg|thumb|A card catalog in the [[University Library of Graz]]]] |

[[Image:Schlagwortkatalog.jpg|thumb|A card catalog in the [[University |

||

Library of Graz]]]] |

|||

Library catalogs originated as [[manuscript]] lists, arranged by format |

|||

Library catalogs originated as [[manuscript]] lists, arranged by format ([[book size|folio]], quarto, etc.) or in a rough alphabetical arrangement by author. Printed catalogs, sometimes called ''dictionary catalogs'', began to be published in the early modern period and enabled scholars outside a library to gain an idea of its contents.<ref>E.g. (1) Radcliffe, John ''Bibliotheca chethamensis: [[Chetham's Library|Bibliothecae publicae Mancuniensis]] ab Humfredo Chetham, armigero fundatae catalogus, exhibens libros in varias classas pro varietate argumenti distributos''; [begun by John Radcliffe, continued by Thoams Jones]. 5 vols. Mancuni: Harrop, 1791-1863. (2) Wright, C. T. Hagberg & Purnell, C. J. ''Catalogue of the [[London Library]], St. James's Square, London''. 10 vols. London, 1913-55. Includes: Supplement: 1913-20. 1920. Supplement: 1920-28. 1929. Supplement: 1928-53. 1953 (in 2 vols). Subject index: (Vol. 1). 1909. Vol. 2: Additions, 1909-22. Vol. 3: Additions, 1923-38. 1938. Vol. 4: (Additions), 1938-53. 1955.</ref> Copies of these in the library itself would sometimes be interleaved with blank leaves on which additions could be recorded, or bound as ''guardbooks'' in which slips of paper were bound in for new entries. Slips could also be kept loose in cardboard or tin boxes, stored on shelves. The first [[index card|card catalogs]] appeared in the late 19th century after the standardization of the 5 in. x 3 in. card for personal filing systems, enabling much more flexibility, and towards the end of the 20th century the Online public access catalog was developed (see below). These gradually became more common as some libraries progressively abandoned such other catalog formats as paper slips (either loose or in sheaf catalog form), and guardbooks. The beginning of the Library of Congress's catalog card service in 1911 led to the use of these cards in the majority of American libraries. An equivalent scheme in the United Kingdom was operated by the [[British National Bibliography]] from 1956<ref>Walford, A. J., ed. (1981) ''Walford's Concise Guide to Reference Material''. London: Library Association; p. 6</ref> and was subscribed to by many public and other libraries. |

|||

([[book size|folio]], quarto, etc.) or in a rough alphabetical |

|||

arrangement by author. Printed catalogs, sometimes called ''dictionary |

|||

catalogs'', began to be published in the early modern period and enabled |

|||

scholars outside a library to gain an idea of its |

|||

contents.<ref>E.g. (1) Radcliffe, John ''Bibliotheca chethamensis: |

|||

[[Chetham's Library|Bibliothecae publicae Mancuniensis]] ab Humfredo |

|||

Chetham, armigero fundatae catalogus, exhibens libros in varias classas |

|||

pro varietate argumenti distributos''; [begun by John Radcliffe, |

|||

continued by Thoams Jones]. 5 vols. Mancuni: Harrop, 1791-1863. (2) |

|||

Wright, C. T. Hagberg & Purnell, C. J. ''Catalogue of the [[London |

|||

Library]], St. James's Square, London''. 10 vols. London, 1913-55. |

|||

Includes: Supplement: 1913-20. 1920. Supplement: 1920-28. 1929. |

|||

Supplement: 1928-53. 1953 (in 2 vols). Subject index: (Vol. 1). 1909. |

|||

Vol. 2: Additions, 1909-22. Vol. 3: Additions, 1923-38. 1938. Vol. 4: |

|||

(Additions), 1938-53. 1955.</ref> Copies of these in the library |

|||

itself would sometimes be interleaved with blank leaves on which |

|||

additions could be recorded, or bound as ''guardbooks'' in which slips |

|||

of paper were bound in for new entries. Slips could also be kept loose |

|||

in cardboard or tin boxes, stored on shelves. The first [[index |

|||

card|card catalogs]] appeared in the late 19th century after the |

|||

standardization of the 5 in. x 3 in. card for personal filing systems, |

|||

enabling much more flexibility, and towards the end of the 20th century |

|||

the Online public access catalog was developed (see below). These |

|||

gradually became more common as some libraries progressively abandoned |

|||

such other catalog formats as paper slips (either loose or in sheaf |

|||

catalog form), and guardbooks. The beginning of the Library of |

|||

Congress's catalog card service in 1911 led to the use of these cards in |

|||

the majority of American libraries. An equivalent scheme in the United |

|||

Kingdom was operated by the [[British National Bibliography]] from |

|||

1956<ref>Walford, A. J., ed. (1981) ''Walford's Concise Guide to |

|||

Reference Material''. London: Library Association; p. 6</ref> and |

|||

was subscribed to by many public and other libraries. |

|||

* c. 245 BC: [[Callimachus]] is considered the first bibliographer and is the one that organized the library by authors and subjects. The ''[[Pinakes]]'' ({{lang-grc|Πίνακες}} "tables") was the first ever library catalogue.<ref>Simon Eliot, Jonathan Rose (2009). "''[http://books.google.com/books?id=R8Pfs146nUAC&pg=PA90&dq&hl=en#v=onepage&q=&f=false |

* c. 245 BC: [[Callimachus]] is considered the first bibliographer and |

||

is the one that organized the library by authors and subjects. The |

|||

''[[Pinakes]]'' ({{lang-grc|Πίνακες}} "tables") was the first ever |

|||

library catalogue.<ref>Simon Eliot, Jonathan Rose (2009). |

|||

"''[http://books.google.com/books?id=R8Pfs146nUAC&pg=PA90&dq&hl=en#v=onepage&q=&f=false |

|||

A Companion to the History of the Book]''". John Wiley and Sons. p.90. |

|||

ISBN 1-4051-9278-X</ref> Variations on this system were used in |

|||

libraries until the late 1800s when [[Melvil Dewey]] developed the |

|||

[[Dewey Decimal Classification]] in 1876, which is still in use today. |

|||

* c. 800: Library catalogues are introduced in the [[House of Wisdom]] and other [[Islamic Golden Age|medieval Islamic]] libraries where books are organized into specific [[genre]]s and categories.<ref>{{citation|last=Micheau|first=Francoise|contribution=The |

* c. 800: Library catalogues are introduced in the [[House of Wisdom]] |

||

and other [[Islamic Golden Age|medieval Islamic]] libraries where books |

|||

are organized into specific [[genre]]s and |

|||

categories.<ref>{{citation|last=Micheau|first=Francoise|contribution=The |

|||

Scientific Institutions in the Medieval Near East|pages=988–991}} in |

|||

{{Harv|Morelon|Rashed|1996|pp=985–1007}}</ref> |

|||

* 1595: ''Nomenclator'' of [[Leiden University Library]] appears, the first printed catalog of an institutional library. |

* 1595: ''Nomenclator'' of [[Leiden University Library]] appears, the |

||

first printed catalog of an institutional library. |

|||

* 1674: Thomas Hyde's catalog for the Bodleian Library. |

* 1674: Thomas Hyde's catalog for the Bodleian Library. |

||

* 1791: |

|||

[http://gslis.simmons.edu/wikis/LIS415OL_History_Encyclopedia/Origins_of_the_Card_Catalog |

|||

The French Cataloging Code of 1791] |

|||

More about the early history of library catalogs has been collected in 1956 by Strout.<ref>Strout, R.F. (1956), "The development of the catalog and cataloging rules", Library Quarterly, Vol.26 No.4, pp.254–75.</ref> |

More about the early history of library catalogs has been collected in |

||

1956 by Strout.<ref>Strout, R.F. (1956), "The development of the |

|||

catalog and cataloging rules", Library Quarterly, Vol.26 No.4, |

|||

pp.254–75.</ref> |

|||

== Sorting == |

== Sorting == |

||

In a title catalog, one can distinguish two sort orders: |

In a title catalog, one can distinguish two sort orders: |

||

* In the ''grammatical'' sort order (used mainly in older catalogs), the |

* In the ''grammatical'' sort order (used mainly in older catalogs), the |

||

most important word of the title is the first sort term. The importance |

|||

of a word is measured by grammatical rules; for example, the first noun |

|||

may be defined to be the most important word. |

|||

* In the ''mechanical'' sort order, the first word of the title is the first sort term. Most new catalogs use this scheme, but still include a trace of the grammatical sort order: they neglect an article (The, A, etc.) at the beginning of the title. |

* In the ''mechanical'' sort order, the first word of the title is the |

||

first sort term. Most new catalogs use this scheme, but still include a |

|||

trace of the grammatical sort order: they neglect an article (The, A, |

|||

etc.) at the beginning of the title. |

|||

The grammatical sort order has the advantage that often, the most important word of the title is also a good keyword (question 3), and it is the word most users remember first when their memory is incomplete. However, it has the disadvantage that many elaborate grammatical rules are needed, so that only expert users may be able to search the catalog without help from a librarian. |

The grammatical sort order has the advantage that often, the most |

||

important word of the title is also a good keyword (question 3), and it |

|||

is the word most users remember first when their memory is incomplete. |

|||

However, it has the disadvantage that many elaborate grammatical rules |

|||

are needed, so that only expert users may be able to search the catalog |

|||

without help from a librarian. |

|||

In some catalogs, person's names are standardized, i. e., the name of the person is always (cataloged and) sorted in a standard form, even if it appears differently in the library material. This standardization is achieved by a process called [[authority control]]. An advantage of the |

In some catalogs, person's names are standardized, i. e., the name of |

||

the person is always (cataloged and) sorted in a standard form, even if |

|||

it appears differently in the library material. This standardization is |

|||

achieved by a process called [[authority control]]. An advantage of the |

|||

authority control is that it is easier to answer question 2 (which |

|||

works of some author does the library have?). On the other hand, it may |

|||

be more difficult to answer question 1 (does the library have some |

|||

specific material?) if the material spells the author in a peculiar |

|||

variant. For the cataloguer, it may incur (too) much work to check |

|||

whether ''Smith, J.'' is ''Smith, John'' or ''Smith, Jack''.<br> |

|||

For some works, even the title can be standardized. The technical term for this is ''[[uniform title]]''. For example, translations and re-editions are sometimes sorted under their original title. In many catalogs, parts of the [[Bible]] are sorted under the standard name of the book(s) they contain. The plays of William Shakespeare are another frequently cited example of the role played by a ''uniform title'' in the library catalog. |

For some works, even the title can be standardized. The technical term |

||

for this is ''[[uniform title]]''. For example, translations and |

|||

re-editions are sometimes sorted under their original title. In many |

|||

catalogs, parts of the [[Bible]] are sorted under the standard name of |

|||

the book(s) they contain. The plays of William Shakespeare are another |

|||

frequently cited example of the role played by a ''uniform title'' in |

|||

the library catalog. |

|||

Many complications about alphabetic sorting of entries arise. Some examples: |

Many complications about alphabetic sorting of entries arise. Some |

||

examples: |

|||

* Some languages know sorting conventions that differ from the language of the catalog. For example, some [[Dutch language|Dutch]] catalogs sort |

* Some languages know sorting conventions that differ from the language |

||

of the catalog. For example, some [[Dutch language|Dutch]] catalogs sort |

|||

''IJ'' as ''Y''. Should an English catalog follow this suit? And should |

|||

a Dutch catalog sort non-Dutch words the same way? |

|||

* Some titles contain numbers, for example ''[[2001: A Space Odyssey (novel)|2001: A Space Odyssey]]''. Should they be sorted as numbers, or spelled out as ''<u>T</u>wo thousand and one''? |

* Some titles contain numbers, for example ''[[2001: A Space Odyssey |

||

(novel)|2001: A Space Odyssey]]''. Should they be sorted as numbers, or |

|||

spelled out as ''<u>T</u>wo thousand and one''? |

|||

* ''[[Honoré de Balzac|de Balzac, Honoré]]'' or ''Balzac, Honoré de''? ''[[José Ortega y Gasset|Ortega y Gasset, José]]'' or ''Gasset, José Ortega y''? |

* ''[[Honoré de Balzac|de Balzac, Honoré]]'' or ''Balzac, Honoré de''? |

||

''[[José Ortega y Gasset|Ortega y Gasset, José]]'' or ''Gasset, José |

|||

Ortega y''? |

|||

For a fuller discussion, see [[collation]]. |

For a fuller discussion, see [[collation]]. |

||

In a subject catalog, one has to decide on which [[library classification|classification]] system to use. The cataloguer will select appropriate subject headings for the bibliographic item and a unique classification number (sometimes known as a "call number") which is used not only for identification but also for the purposes of shelving, placing items with similar subjects near one another, which aids in browsing by library users, who are thus often able to take advantage of [[serendipity]] in their search process. |

In a subject catalog, one has to decide on which [[library |

||

classification|classification]] system to use. The cataloguer will |

|||

select appropriate subject headings for the bibliographic item and a |

|||

unique classification number (sometimes known as a "call number") which |

|||

is used not only for identification but also for the purposes of |

|||

shelving, placing items with similar subjects near one another, which |

|||

aids in browsing by library users, who are thus often able to take |

|||

advantage of [[serendipity]] in their search process. |

|||

== Online catalogs == |

== Online catalogs == |

||

[[File:Screenshot_of_Dynix_library_automation_software.png|thumb|right|[[Dynix |

[[File:Screenshot_of_Dynix_library_automation_software.png|thumb|right|[[Dynix |

||

(software)|Dynix]], an early but popular and long-lasting online |

|||

catalog.]] |

|||

[[File:Card Division of the Library of Congress 3c18631u original.jpg|thumb|right|People working in Card Division, [[Library of Congress]], Washington, D.C., 1910s or 1920s]] |

[[File:Card Division of the Library of Congress 3c18631u |

||

original.jpg|thumb|right|People working in Card Division, [[Library of |

|||

Congress]], Washington, D.C., 1910s or 1920s]] |

|||

Online cataloging, such as [[Dynix (software)|Dynix]], has greatly enhanced the usability of catalogs, thanks to the rise of MAchine Readable Cataloging = [[MARC standards]] in the 1960s. Rules governing the creation of catalog MARC records include not only formal cataloging rules like [[AACR2]] but also special rules specific to MARC, available from the [[Library of Congress]] and also [[OCLC]]. MARC was originally |

Online cataloging, such as [[Dynix (software)|Dynix]], has greatly |

||

enhanced the usability of catalogs, thanks to the rise of MAchine |

|||

Readable Cataloging = [[MARC standards]] in the 1960s. Rules governing |

|||

the creation of catalog MARC records include not only formal cataloging |

|||

rules like [[AACR2]] but also special rules specific to MARC, available |

|||

from the [[Library of Congress]] and also [[OCLC]]. MARC was originally |

|||

used to automate the creation of physical catalog cards; Now the MARC |

|||

computer files are accessed directly in the search process. OPACs have |

|||

enhanced usability over traditional card formats because: |

|||

# The online catalog does not need to be sorted statically; the user can |

# The online catalog does not need to be sorted statically; the user can |

||

choose author, title, keyword, or systematic order dynamically. |

|||

# Most online catalogs offer a search facility for any word of the title; the goal of the grammatic word order (provide an entry on the word that most users would look for) is reached even better. |

# Most online catalogs offer a search facility for any word of the |

||

title; the goal of the grammatic word order (provide an entry on the |

|||

word that most users would look for) is reached even better. |

|||

# Many online catalogs allow links between several variants of an author |

# Many online catalogs allow links between several variants of an author |

||

name. So, authors can be found both under the original and the |

|||

standardised name (if entered properly by the cataloguer). |

|||

# The elimination of paper cards has made the information more accessible to many people with disabilities, such as the [[visually impaired]], [[wheelchair]] users, and those who suffer from [[Mold health issues|mold]] allergies. |

# The elimination of paper cards has made the information more |

||

accessible to many people with disabilities, such as the [[visually |

|||

impaired]], [[wheelchair]] users, and those who suffer from [[Mold |

|||

health issues|mold]] allergies. |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

| Line 100: | Line 246: | ||

==Other sources== |

==Other sources== |

||

* Chan, Lois Mai. ''Cataloging and Classification: An Introduction''. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994. |

* Chan, Lois Mai. ''Cataloging and Classification: An Introduction''. |

||

New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994. |

|||

*{{Citation |

*{{Citation |

||

|last1=Morelon |

|last1=Morelon |

||

| Line 112: | Line 259: | ||

|isbn=0-415-12410-7 |

|isbn=0-415-12410-7 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

* Svenonius, Elaine. ''The Intellectual Foundation of Information Organization''. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2000. |

* Svenonius, Elaine. ''The Intellectual Foundation of Information |

||

Organization''. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2000. |

|||

*Taylor, Archer (1986) ''Book Catalogues: their varieties and uses''; 2nd ed., introductions, corrections and additions by W. P. Barlow, Jr. Winchester: St Paul's Bibliographies (Previous ed.: Chicago: Newberry Library, 1957) |

*Taylor, Archer (1986) ''Book Catalogues: their varieties and uses''; |

||

2nd ed., introductions, corrections and additions by W. P. Barlow, Jr. |

|||

Winchester: St Paul's Bibliographies (Previous ed.: Chicago: Newberry |

|||

Library, 1957) |

|||

*[[James C. M. Hanson|Hanson, James C. M.]] ''Catalog rules; author and title entries'' (Chicago: American Library Association. 1908) |

*[[James C. M. Hanson|Hanson, James C. M.]] ''Catalog rules; author and |

||

title entries'' (Chicago: American Library Association. 1908) |

|||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

{{commons category|Card catalogs}} |

{{commons category|Card catalogs}} |

||

* [http://www.ifla.org/VII/s13/pubs/isbdg.htm A general overview of the |

* [http://www.ifla.org/VII/s13/pubs/isbdg.htm A general overview of the |

||

ISBD] |

|||

* {{LISWiki link|History of the card catalog}} |

* {{LISWiki link|History of the card catalog}} |

||

* [http://faculty.quinnipiac.edu/libraries/tballard/webpacs.html Very Innovative Webpacs — Online catalogs using particularly good design or functionality] |

* [http://faculty.quinnipiac.edu/libraries/tballard/webpacs.html Very |

||

Innovative Webpacs — Online catalogs using particularly good |

|||

design or functionality] |

|||

* [http://librariesaustralia.nla.gov.au Libraries Australia] — Australian national bibliographic catalogue: 800+ libraries |

* [http://librariesaustralia.nla.gov.au Libraries Australia] — |

||

Australian national bibliographic catalogue: 800+ libraries |

|||

* [http://worldcat.org/ OCLC WorldCat] |

* [http://worldcat.org/ OCLC WorldCat] |

||

* [http://www.flickr.com/photos/annarbor/sets/72157623414542180 Flickr]. |

* [http://www.flickr.com/photos/annarbor/sets/72157623414542180 Flickr]. |

||

Photos of University of Michigan Library Card Catalog, 2010 |

|||

* [http://www.kvapak.com/en Kvapak], Spatial positioning of books in the |

* [http://www.kvapak.com/en Kvapak], Spatial positioning of books in the |

||

library |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Library Catalog}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Library Catalog}} |

||

Revision as of 16:21, 22 November 2012

A library catalog (or library catalogue) is a register of all bibliographic items found in a library or group

of libraries, such as a network of libraries at several locations. A

bibliographic item can be any information entity (e.g., books, computer files, graphics, realia, cartographic materials, etc.) that is considered library material (e.g., a single novel in an anthology), or a group of library materials (e.g., a

trilogy), or linked from the catalog (e.g., a webpage) as far as it is relevant to the catalog and to the users (patrons) of the library.

The card catalog was a familiar sight to library users for generations, but it has been effectively replaced by the [[online public

access catalog]] (OPAC). Some still refer to the online catalog as a

"card catalog". Some libraries with OPAC access still have card catalogs on site, but these are now strictly a secondary resource and are seldom updated. Many of the libraries that have retained their physical card catalog post a sign advising the last year that the card catalog was updated. Some libraries have eliminated their card catalog in favour of the OPAC for the purpose of saving space for other use, such as additional shelving.

Goal

Charles Ammi Cutter made the first explicit statement regarding the objectives of a bibliographic system in his [http://books.google.com/books?id=rj-f4-Ps-AkC&printsec=frontcover Rules for a Printed Dictionary Catalog] in 1876. According to Cutter, those objectives were

1. to enable a person to find a book of which either (Identifying objective)

- the author

- the title

- the subject

- the category

is known.

2. to show what the library has (Collocating objective)

- by a given author

- on a given subject

- in a given kind of literature

3. to assist in the choice of a book (Evaluating objective)

- as to its edition (bibliographically)

- as to its character (literary or topical)

These objectives can still be recognized in more modern definitions formulated throughout the 20th century. 1960/61 Cutter's objectives were

revised by Lubetzky and the Conference on Cataloging Principles (CCP)

in Paris. The latest attempt to describe a library catalog's goals and functions was made in 1998 with [[Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records]] (FRBR) which defines four user tasks: find, identify, select, and obtain.

Catalog card

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2012) |

Main entry e.g.

Arif, Abdul Majid.

Political structure in a changing Pakistani

village / by Abdul Majid Arif and Basharat Hafeez

Andaleeb. -- 2nd ed. -- Lahore : ABC Press, 1985.

xvi, 367p. : ill. ; 22 cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 969-8612-02-8

Types

History

Library catalogs originated as manuscript lists, arranged by format (folio, quarto, etc.) or in a rough alphabetical arrangement by author. Printed catalogs, sometimes called dictionary catalogs, began to be published in the early modern period and enabled

scholars outside a library to gain an idea of its

contents.[1] Copies of these in the library itself would sometimes be interleaved with blank leaves on which additions could be recorded, or bound as guardbooks in which slips of paper were bound in for new entries. Slips could also be kept loose in cardboard or tin boxes, stored on shelves. The first [[index card|card catalogs]] appeared in the late 19th century after the standardization of the 5 in. x 3 in. card for personal filing systems, enabling much more flexibility, and towards the end of the 20th century the Online public access catalog was developed (see below). These gradually became more common as some libraries progressively abandoned such other catalog formats as paper slips (either loose or in sheaf catalog form), and guardbooks. The beginning of the Library of Congress's catalog card service in 1911 led to the use of these cards in

the majority of American libraries. An equivalent scheme in the United

Kingdom was operated by the British National Bibliography from 1956[2] and

was subscribed to by many public and other libraries.

- c. 245 BC: Callimachus is considered the first bibliographer and

is the one that organized the library by authors and subjects. The Pinakes (Ancient Greek: Πίνακες "tables") was the first ever library catalogue.[3] Variations on this system were used in libraries until the late 1800s when Melvil Dewey developed the Dewey Decimal Classification in 1876, which is still in use today.

- c. 800: Library catalogues are introduced in the House of Wisdom

and other medieval Islamic libraries where books are organized into specific genres and categories.[4]

- 1595: Nomenclator of Leiden University Library appears, the

first printed catalog of an institutional library.

- 1674: Thomas Hyde's catalog for the Bodleian Library.

- 1791:

[http://gslis.simmons.edu/wikis/LIS415OL_History_Encyclopedia/Origins_of_the_Card_Catalog

The French Cataloging Code of 1791]

More about the early history of library catalogs has been collected in 1956 by Strout.[5]

Sorting

In a title catalog, one can distinguish two sort orders:

- In the grammatical sort order (used mainly in older catalogs), the

most important word of the title is the first sort term. The importance of a word is measured by grammatical rules; for example, the first noun may be defined to be the most important word.

- In the mechanical sort order, the first word of the title is the

first sort term. Most new catalogs use this scheme, but still include a trace of the grammatical sort order: they neglect an article (The, A, etc.) at the beginning of the title. The grammatical sort order has the advantage that often, the most important word of the title is also a good keyword (question 3), and it is the word most users remember first when their memory is incomplete. However, it has the disadvantage that many elaborate grammatical rules are needed, so that only expert users may be able to search the catalog without help from a librarian.

In some catalogs, person's names are standardized, i. e., the name of the person is always (cataloged and) sorted in a standard form, even if it appears differently in the library material. This standardization is achieved by a process called authority control. An advantage of the

authority control is that it is easier to answer question 2 (which

works of some author does the library have?). On the other hand, it may

be more difficult to answer question 1 (does the library have some

specific material?) if the material spells the author in a peculiar

variant. For the cataloguer, it may incur (too) much work to check

whether Smith, J. is Smith, John or Smith, Jack.

For some works, even the title can be standardized. The technical term

for this is uniform title. For example, translations and

re-editions are sometimes sorted under their original title. In many

catalogs, parts of the Bible are sorted under the standard name of

the book(s) they contain. The plays of William Shakespeare are another

frequently cited example of the role played by a uniform title in

the library catalog.

Many complications about alphabetic sorting of entries arise. Some examples:

- Some languages know sorting conventions that differ from the language

of the catalog. For example, some Dutch catalogs sort

IJ as Y. Should an English catalog follow this suit? And should a Dutch catalog sort non-Dutch words the same way?

- Some titles contain numbers, for example [[2001: A Space Odyssey

(novel)|2001: A Space Odyssey]]. Should they be sorted as numbers, or spelled out as Two thousand and one?

- de Balzac, Honoré or Balzac, Honoré de?

Ortega y Gasset, José or Gasset, José Ortega y? For a fuller discussion, see collation.

In a subject catalog, one has to decide on which [[library classification|classification]] system to use. The cataloguer will select appropriate subject headings for the bibliographic item and a unique classification number (sometimes known as a "call number") which is used not only for identification but also for the purposes of shelving, placing items with similar subjects near one another, which aids in browsing by library users, who are thus often able to take advantage of serendipity in their search process.

Online catalogs

[[File:Card Division of the Library of Congress 3c18631u original.jpg|thumb|right|People working in Card Division, [[Library of Congress]], Washington, D.C., 1910s or 1920s]] Online cataloging, such as Dynix, has greatly enhanced the usability of catalogs, thanks to the rise of MAchine Readable Cataloging = MARC standards in the 1960s. Rules governing the creation of catalog MARC records include not only formal cataloging rules like AACR2 but also special rules specific to MARC, available from the Library of Congress and also OCLC. MARC was originally

used to automate the creation of physical catalog cards; Now the MARC

computer files are accessed directly in the search process. OPACs have enhanced usability over traditional card formats because:

- The online catalog does not need to be sorted statically; the user can

choose author, title, keyword, or systematic order dynamically.

- Most online catalogs offer a search facility for any word of the

title; the goal of the grammatic word order (provide an entry on the word that most users would look for) is reached even better.

- Many online catalogs allow links between several variants of an author

name. So, authors can be found both under the original and the

standardised name (if entered properly by the cataloguer).

- The elimination of paper cards has made the information more

accessible to many people with disabilities, such as the [[visually impaired]], wheelchair users, and those who suffer from [[Mold health issues|mold]] allergies.

See also

- AACR2

- Cataloging

- Collation

- Dewey Decimal Classification

- Dialcat

- Dynix

- International Standard Bibliographic Description

- Nomenclature

- Social cataloging applications

- Union catalog

References

- ^ E.g. (1) Radcliffe, John Bibliotheca chethamensis: Bibliothecae publicae Mancuniensis ab Humfredo Chetham, armigero fundatae catalogus, exhibens libros in varias classas pro varietate argumenti distributos; [begun by John Radcliffe, continued by Thoams Jones]. 5 vols. Mancuni: Harrop, 1791-1863. (2) Wright, C. T. Hagberg & Purnell, C. J. Catalogue of the [[London Library]], St. James's Square, London. 10 vols. London, 1913-55. Includes: Supplement: 1913-20. 1920. Supplement: 1920-28. 1929. Supplement: 1928-53. 1953 (in 2 vols). Subject index: (Vol. 1). 1909. Vol. 2: Additions, 1909-22. Vol. 3: Additions, 1923-38. 1938. Vol. 4: (Additions), 1938-53. 1955.

- ^ Walford, A. J., ed. (1981) Walford's Concise Guide to Reference Material. London: Library Association; p. 6

- ^ Simon Eliot, Jonathan Rose (2009). "[http://books.google.com/books?id=R8Pfs146nUAC&pg=PA90&dq&hl=en#v=onepage&q=&f=false A Companion to the History of the Book]". John Wiley and Sons. p.90. ISBN 1-4051-9278-X

- ^ Micheau, Francoise, "The

Scientific Institutions in the Medieval Near East", pp. 988–991

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); line feed character in|contribution=at position 4 (help) in (Morelon & Rashed 1996, pp. 985–1007) - ^ Strout, R.F. (1956), "The development of the catalog and cataloging rules", Library Quarterly, Vol.26 No.4, pp.254–75.

Other sources

- Chan, Lois Mai. Cataloging and Classification: An Introduction.

New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994.

- Morelon, Régis; Rashed, Roshdi (1996), Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, vol. 3, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-12410-7

- Svenonius, Elaine. The Intellectual Foundation of Information

Organization. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2000.

- Taylor, Archer (1986) Book Catalogues: their varieties and uses;

2nd ed., introductions, corrections and additions by W. P. Barlow, Jr. Winchester: St Paul's Bibliographies (Previous ed.: Chicago: Newberry Library, 1957)

- Hanson, James C. M. Catalog rules; author and

title entries (Chicago: American Library Association. 1908)

External links

- [http://www.ifla.org/VII/s13/pubs/isbdg.htm A general overview of the

ISBD]

Innovative Webpacs — Online catalogs using particularly good design or functionality]

Australian national bibliographic catalogue: 800+ libraries

Photos of University of Michigan Library Card Catalog, 2010

- Kvapak, Spatial positioning of books in the

library