Parlement of Foules: Difference between revisions

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

<br>36<br>37<br>38<br>39<br>40<br>41<br>42<br> |

<br>36<br>37<br>38<br>39<br>40<br>41<br>42<br> |

||

<br> |

<br> |

||

<br> |

<br>43<br>44<br>45<br>46<br>47<br>48<br>49<br> |

||

<br> |

<br> |

||

<br> |

<br>50<br>51<br>52<br>53<br>54<br>55<br>56<br> |

||

<br> |

<br> |

||

<br> |

<br>57<br>58<br>59<br>60<br>61<br>62<br>63<br> |

||

<br> |

<br> |

||

<br> |

<br>64<br>65<br>66<br>67<br>68<br>69<br>70<br> |

||

<br> |

<br> |

||

<br> |

<br>71<br>72<br>73<br>74<br>75<br>76<br>77<br> |

||

<br> |

<br> |

||

<br> |

<br>78<br>79<br>80<br> 81<br> 82<br> 83<br> 84<br> |

||

<br> |

<br> |

||

<br> |

<br> 85<br> 86<br> 87<br> 88<br> 89<br> 90<br> 91<br> |

||

<br> |

<br> |

||

<br> |

<br> 92<br> 93<br> 94<br> 95<br> 96<br> 97<br> 98<br> |

||

<br> |

<br> |

||

<br> |

<br> 99<br>100<br>101<br>102<br>103<br>104<br>105<br> |

||

<br> |

|||

<br>22<br>23<br>24<br>25<br>26<br>27<br>28<br> |

|||

<br> |

|||

<br>29<br>30<br>31<br>32<br>33<br>34<br>35<br> |

|||

<br> |

|||

<br>36<br>37<br>38<br>39<br>40<br>41<br>42<br> |

|||

|| |

|| |

||

The lyf so short, the craft so long to lerne,<br> |

The lyf so short, the craft so long to lerne,<br> |

||

Revision as of 20:35, 18 June 2011

The "Parlement of Foules" (also known as the "Parliament of Fowls", "Parlement of Briddes", "Assembly of Fowls", "Assemble of Foules", or "The Parliament of Birds") is a poem by Geoffrey Chaucer (1343?-1400) made up of approximately 700 lines. The poem is in the form of a dream vision in rhyme royal stanza and is interesting in that it is the first reference to the idea that St. Valentine's Day was a special day for lovers.[1]

Summary

The poem begins with the narrator reading Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis in the hope of learning some “certeyn thing.” When he falls asleep Scipio Africanus appears and guides him up through the celestial spheres to Venus’s temple. The narrator then passes through Venus’s dark temple with its friezes of doomed lovers and out into the bright sunlight where Nature is convening a parliament at which the birds all choose their mates. There three tercel eagles make their case for the hand of a formel eagle until the birds of the lower estates begin to protest and launch into a comic parliamentary debate, which Nature herself finally ends. None of the tercels wins the formel, for Nature allows her to put off her decision for another year (indeed, female birds of prey often become sexually mature at one year of age, males only at two years). Nature allows the other birds, however, to pair off. The dream ends with a song welcoming the new summer. The dreamer awakes, still unsatisfied, and returns to his books, hoping still to learn the thing for which he seeks.

Manuscripts

There are fifteen manuscript sources for the poem:

- British Library, Harley 7333

- Cambridge University Library Gg. IV.27

- Cambridge University Library Ff. I.6 (Findern)

- Cambridge University Library Hh.IV.12 (incomplete)

- Pepys 2006, Magdalene College, Cambridge

- Trinity College, Cambridge R.III.19

- Bodleian Library, Arch. Selden B.24

- Bodleian Library, Laud Misc. 416

- Bodleian Library, Fairfax 16

- Bodleian Library, Bodley 638

- Bodleian Library, Tanner 346

- Bodleian Library, Digby 181

- St. John's College, Oxford, J LVII

- Longleat 258, Longleat House, Warminster, Wilts

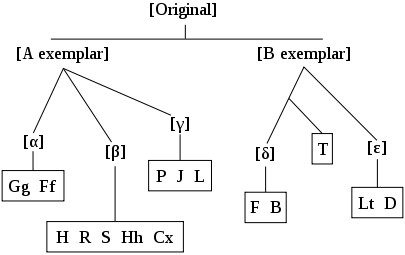

William Caxton's early print of 1478 is also considered authoritative, for it reproduces the text of a manuscript now considered lost. The stemma and genealogy of these authorities was studied by John Koch in 1881, and later established by Eleanor Prescott Hammond in 1902, dividing them into two main groups, A and B (last five MSS), although the stemma is by no means definitive.

Concerning the author of the poem, there is no doubt that it was written by Geoffrey Chaucer, for so he tells us twice in his works.

- The first time is in the Introduction (Prologue) to The Legend of Good Women: "He made the book that hight the Hous of Fame, / And eke the Deeth of Blaunche the Duchesse, / And the Parlement of Foules, as I gesse" (Larry D. Benson, The Riverside Chaucer, 1987: 600).

- The second allusion is found in the Retractation to The Canterbury Tales: "the book of the Duchesse; the book of Seint Valentynes day of the Parlement of Briddes" (Benson 1987: 328).

A more difficult question is that of date. Early criticism of the poem, as far as the first decades of the 20th century, relied mainly on the different interpretations of the text — comparing the fight for the female eagle with royal betrothals of the age — to produce a date of composition for the poem. Fred N. Robinson (Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, 1957: 791) mentioned that "if the theories of allegory in the Parliament are rejected, the principal evidence usually relied on for dating the poem about 1381-2 disappears." Later criticism, however, is much more objective on the reasons why the poem has been dated in 1382, the main reason given in lines 117-118 of the poem itself: "As wisly as I sawe the [Venus], northe northe west / When I begane my sweuene for to write" for according to John M. Manly (1913: 279-90) Venus is never strictly in the position "north-north-west,"but it can be easily thought to be so when it reaches its extreme northern point". Manly adds that this condition was met in May 1374, 1382, and 1390.

The third date is easily discarded since we know that the poem is already mentioned as composed in the Prologue to The Legend of Good Women. Derek Brewer (1960: 104) then argues that the date of 1382, as opposed to that of 1374, is much more likely for the composition of the poem since, during the same period (1373-85), Chaucer wrote many other works including The House of Fame which, in all respects, seems to have been composed earlier than "The Parliament of Fowls," thus: "a very reasonable, if not certain, date for the Parlement is that it was begun in May 1382, and was ready for St. Valentine's Day, 14th February 1383" (Brewer, 1960: 104). Although much of the criticism on the interpretation of "The Parliament of Fowls" — which would render clues for its date of composition — is contradictory, and criticism about the importance of line 117 does not agree on whether it can be taken as serious evidence for the dating of the poem, there is nowadays a general agreement among scholars as to 1381-1382 being the date of composition for "The Parliament of Fowls."

The Poem

|

|

The lyf so short, the craft so long to lerne, |

The life so short, the craft so long to learn, |

Example | Example | ||

| Example | Example | |||||

| Example | Example | |||||

| Example | Example | |||||

| Example | Example | |||||

| Example | Example | |||||

| Example | Example | |||||

| Example | Example | |||||

| Example | Example |

References

- ^ Oruch, Jack B., "St. Valentine, Chaucer, and Spring in February," Speculum, 56 (1981): 534–65. Oruch's survey of the literature finds no association between Valentine and romance prior to Chaucer. He concludes that Chaucer is likely to be "the original mythmaker in this instance." Colfa.utsa.edu

- Benson, Larry D., ed. The Riverside Chaucer, 3rd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987.

External links

- Modern Prose Translation and Other Resources at eChaucer

- The Dream Poems – modernised versions A. S. Kline