Paul Revere: Difference between revisions

Flatterworld (talk | contribs) |

[MASS ABUSE ALERT] BEWARE of "revisionist" tea partiers falsely rewriting history and spamming this page to cover up Sarah Palin's misquotes. |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

| signature = |

| signature = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Paul Revere''' ({{OldStyleDate|bapt. January 1, 1735||December 21, 1734}}{{ndash}}May 10, 1818)<ref name= "Birthdate">Revere's date of baptism is confused by the conversion between the [[Julian calendar|Julian]] and [[Gregorian calendar]]s, which offsets the date by 10 days. While the baptism was recorded on December 22, adjusting for the conversion between Julian and Gregorian calendars changes the date to January 1.</ref> was an American [[silversmith]] and a [[Patriot (American Revolution)|patriot]] in the [[American Revolution]]. After his death the poet [[Henry Wadsworth Longfellow| Longfellow]] made him famous by celebrating his deed of being a messenger in the [[battles of Lexington and Concord]]. As a result, his "midnight ride" to warn the people that the |

'''Paul Revere''' ({{OldStyleDate|bapt. January 1, 1735||December 21, 1734}}{{ndash}}May 10, 1818)<ref name= "Birthdate">Revere's date of baptism is confused by the conversion between the [[Julian calendar|Julian]] and [[Gregorian calendar]]s, which offsets the date by 10 days. While the baptism was recorded on December 22, adjusting for the conversion between Julian and Gregorian calendars changes the date to January 1.</ref> was an American [[silversmith]] and a [[Patriot (American Revolution)|patriot]] in the [[American Revolution]]. After his death the poet [[Henry Wadsworth Longfellow| Longfellow]] made him permanently famous by celebrating his deed of being a messenger in the [[battles of Lexington and Concord]]. As a result, his "midnight ride" to warn the people that the British were coming is an eminent part of [[United States]] history. |

||

Revere was a prosperous and prominent [[Boston]] silversmith, who helped organize an [[intelligence in the American Revolutionary War|intelligence and alarm]] system to keep watch on the [[Kingdom of Great Britain|British]] military. |

Revere was a prosperous and prominent [[Boston]] silversmith, who helped organize an [[intelligence in the American Revolutionary War|intelligence and alarm]] system to keep watch on the [[Kingdom of Great Britain|British]] military. |

||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

Revere, Dawes, and Prescott were detained by a British Army patrol in [[Lincoln, Massachusetts|Lincoln]] at a roadblock on the way to Concord.<ref name=Boatner622/> Prescott jumped his horse over a wall and escaped into the woods; he eventually reached Concord. Dawes also escaped, though he fell off his horse not long after and did not complete the ride.<ref>Fischer, pp. 131–2, 144.</ref><ref name=Forbes>{{cite book |title = Paul Revere and the World He Lived in | last=Forbes | first=Esther | publisher = Mariner Books|year = October 1, 1999 | pages = 262–3 | isbn=978-0618001941}}</ref> |

Revere, Dawes, and Prescott were detained by a British Army patrol in [[Lincoln, Massachusetts|Lincoln]] at a roadblock on the way to Concord.<ref name=Boatner622/> Prescott jumped his horse over a wall and escaped into the woods; he eventually reached Concord. Dawes also escaped, though he fell off his horse not long after and did not complete the ride.<ref>Fischer, pp. 131–2, 144.</ref><ref name=Forbes>{{cite book |title = Paul Revere and the World He Lived in | last=Forbes | first=Esther | publisher = Mariner Books|year = October 1, 1999 | pages = 262–3 | isbn=978-0618001941}}</ref> |

||

Revere was |

Revere was questioned by the British officers and told them of the army's movement from Boston, and that British army troops might be in some danger if they approached Lexington, because of the large number of hostile militia gathered there.<ref>Fischer, pp. 133–134</ref> He and other captives taken by the patrol were then escorted east toward Lexington, until the sound of musket fire from the town center alarmed the patrolmen. Revere explained to them that it was probably an arriving militia company that had fired a volley upon its arrival. The sound was followed not long after by the pealing of the town bell.<ref>Fischer, pp. 135–6</ref> The British confiscated Revere's horse, and rode off to warn the approaching army column. Revere was horseless and walked through a cemetery and pastures until he came to Rev. Clarke's house where Hancock and Adams were staying. As the battle on Lexington Green continued, Revere helped John Hancock and his family escape from Lexington with their possessions, including a trunk of Hancock's papers.<ref name=Forbes /> |

||

The ride of the three men triggered a flexible system of {{q |alarm and muster}} that had been carefully developed months before, in reaction to the colonists' impotent response to the [[Powder Alarm]] of September 1774. This system was an improved version of an old network of widespread notification and fast deployment of local militia forces in times of emergency. The colonists had periodically used this system all the way back to the early years of Indian wars in the colony, before it fell into disuse in the [[French and Indian War]]. In addition to other express riders delivering messages, bells, drums, alarm guns, bonfires and a trumpet were used for rapid communication from town to town, notifying the rebels in dozens of eastern Massachusetts villages that they should muster their militias because the regulars in numbers greater than 500 were leaving Boston, with possible hostile intentions. This system was so effective that people in towns {{convert|25|mi|km}} from Boston were aware of the army's movements while they were still unloading boats in Cambridge.<ref name="Fischer138">Fischer, pp. 138–45.</ref> Unlike in the Powder Alarm, the alarm raised by the three riders successfully allowed the militia to repel the British troops in Concord, after which the British were harried by the growing colonial militia all the way back to Boston. |

The ride of the three men triggered a flexible system of {{q |alarm and muster}} that had been carefully developed months before, in reaction to the colonists' impotent response to the [[Powder Alarm]] of September 1774. This system was an improved version of an old network of widespread notification and fast deployment of local militia forces in times of emergency. The colonists had periodically used this system all the way back to the early years of Indian wars in the colony, before it fell into disuse in the [[French and Indian War]]. In addition to other express riders delivering messages, bells, drums, alarm guns, bonfires and a trumpet were used for rapid communication from town to town, notifying the rebels in dozens of eastern Massachusetts villages that they should muster their militias because the regulars in numbers greater than 500 were leaving Boston, with possible hostile intentions. This system was so effective that people in towns {{convert|25|mi|km}} from Boston were aware of the army's movements while they were still unloading boats in Cambridge.<ref name="Fischer138">Fischer, pp. 138–45.</ref> Unlike in the Powder Alarm, the alarm raised by the three riders successfully allowed the militia to repel the British troops in Concord, after which the British were harried by the growing colonial militia all the way back to Boston. |

||

| Line 119: | Line 119: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Commons|Paul Revere}} |

{{Commons|Paul Revere}} |

||

*[http://www.paulreverehouse.org/ride/ An interactive map showing the routes taken by Revere, Dawes, and Prescott is available at ''The Paul Revere House'' website] |

|||

*{{Wikisource1911Enc Citation|Revere, Paul}} |

*{{Wikisource1911Enc Citation|Revere, Paul}} |

||

*[http://www.paul-revere-heritage.com/ Paul Revere Heritage Project] |

*[http://www.paul-revere-heritage.com/ Paul Revere Heritage Project] |

||

*[http://www.paulreverehouse.org/ The Paul Revere House] |

*[http://www.paulreverehouse.org/ The Paul Revere House] |

||

*[http://revererollingmill.googlepages.com/ Revere Rolling Mill] (about the endangered original Revere copper works site in Canton, MA) |

|||

*[http://www.sec.state.ma.us/arc/arcidx.htm Original copper engravings and other documents in collections of the Massachusetts State Archives] |

*[http://www.sec.state.ma.us/arc/arcidx.htm Original copper engravings and other documents in collections of the Massachusetts State Archives] |

||

*{{Worldcat id|lccn-n80-37041}} |

|||

*[http://revererollingmill.googlepages.com/ Revere Rolling Mill] (about the endangered original Revere copper works site in Canton, MA) |

|||

{{Persondata |

{{Persondata |

||

| NAME =Revere, Paul |

| NAME =Revere, Paul |

||

Revision as of 19:05, 6 June 2011

Paul Revere | |

|---|---|

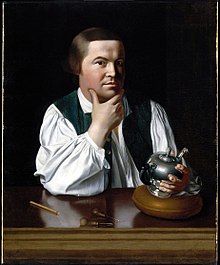

Portrait of Paul Revere by John Singleton Copley, c. 1768–70 | |

| Born | December 21, 1734 |

| Died | Error: Need valid birth date (second date): year, month, day |

| Occupation(s) | silversmith, colonial militia officer |

| Spouse(s) | Sarah Orne (1757–73) (her death) Rachel Walker (1773–1813) (her death) |

| Children | 8 with Sarah Orne (6 survived) 8 with Rachel Walker (5 survived) |

Paul Revere (bapt. January 1, 1735 [O.S. December 21, 1734]–May 10, 1818)[1] was an American silversmith and a patriot in the American Revolution. After his death the poet Longfellow made him permanently famous by celebrating his deed of being a messenger in the battles of Lexington and Concord. As a result, his "midnight ride" to warn the people that the British were coming is an eminent part of United States history.

Revere was a prosperous and prominent Boston silversmith, who helped organize an intelligence and alarm system to keep watch on the British military. Revere later served as an officer in the Penobscot Expedition, one of the most disastrous campaigns of the American Revolutionary War, for which he was absolved of blame.

Early years

Revere was likely born in very late December, 1734, in Boston's North End, the son of a French Huguenot father and a Boston mother. Revere had eleven siblings with whom he appears to have been not particularly close. He was the third oldest child and the eldest surviving son. Revere's father, born Apollos Rivoire, came to Boston at the age of 13 and was apprenticed to the silversmith John Coney. By the time he married Deborah Hichborn, a member of a long-standing Boston family that owned a small shipping wharf, Rivoire had anglicized his name to Paul Revere. Apollos (now Paul) passed his silver trade to his son Paul. Upon Apollos' death in 1754, Paul was too young by law to officially be the master of the family silver shop; Deborah probably assumed control of the business, while Paul and one of his younger brothers did the silver work. Revere fought briefly in the Seven Years' War (French and Indian War), serving as a second lieutenant in an artillery regiment that attempted to take the French fort at Crown Point, in present day New York. Upon leaving the army, Revere returned to Boston and assumed control of the silver shop in his own name. One of the skills that distinguished him from other silversmiths was that he was not only an expert smith but also a skilled engraver and one of the few craftsmen who could complete a piece of silver, even to the engraved decoration. The daybooks of his shop that survived to our days document that among more than 5,000 products crafted by the shop there were many small and affordable items such as buckles, buttons, rings and beads. He was also a prominent Freemason.[2]

Revere's silver work quickly gained attention in Boston; at the same time, he was befriending numerous political agitators, including Dr. Joseph Warren and James Otis. On August 4, 1757, Paul Revere married Sarah Orne (1736–73), who bore eight children, six of whom survived. During the 1760s, Revere produced a number of political engravings and advertised as a dentist, and became increasingly involved in the actions of the Sons of Liberty. In 1770, he purchased the house in North Square which is now open to the public. One of his engravings was done in the wake of the Boston Massacre in March of 1770. It is not known whether Revere was present during the Massacre, though his detailed map of the bodies, meant to be used in the trial of the British soldiers held responsible, suggests that he had first-hand knowledge.[3] Sarah died in 1773, and on October 10 of that year Revere married Rachel Walker (1745–1813), with whom he would have five more surviving children.

After the Boston Tea Party in 1773, Revere began work as a courier for the Boston Committee of Public Safety, riding messages to New York and Philadelphia about the political unrest in the city.[4] In 1774, the military governor of Massachusetts, General Thomas Gage, closed the port of Boston, began to quarter soldiers in great numbers all around Boston, and dissolved the provincial assembly. During this time Revere gathered and disseminated intelligence by (QWATCHING THE MOVEMENTS OF BRITISH SOLDIERS), as he wrote in an account of his ride. Around this time Revere contributed engravings to the patriot monthly Royal American Magazine.[5] At this time, his silver business was much less lucrative, and was largely in the hands of his son, Paul Revere, Jr. Accounting books from the business show gaps that correspond with Revere's resistance activity.[4] As 1775 began, revolution was imminent and Revere was more involved with the Sons of Liberty than ever. He rode to Portsmouth, New Hampshire in December 1774 upon rumors of an impending landing of British troops there;[6] the rumors turned out to be false, but the ride sparked New Hampshire militia to raid Fort William and Mary for its gunpowder supply.[7] Revere's activities gained some notoriety as far away as London in 1774 and 1775. He was mentioned in newspaper articles as "Ambassador for the Committee of Correspondence of Boston to the Congress of Philadelphia". While an overstatement, Revere was indeed suited for the role.[4]

"Midnight Ride"

On April 14, 1775, General Gage received instructions from Secretary of State William Legge, Earl of Dartmouth, to disarm the rebels, who were known to have hidden weapons in Concord, among other locations, and to imprison the rebellion's leaders, especially Samuel Adams and John Hancock. Dartmouth gave Gage considerable discretion in his commands.[8][9] Gage issued orders to Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith to proceed from Boston [[d:Special:EntityPage/QWITH UTMOST EXPEDITION AND SECRECY TO CONCORD, WHERE YOU WILL SEIZE AND DESTROY... ALL MILITARY STORES... BUT YOU WILL TAKE CARE THAT THE SOLDIERS DO NOT PLUNDER THE INHABITANTS OR HURT PRIVATE PROPERTY.| (QWITH UTMOST EXPEDITION AND SECRECY TO CONCORD, WHERE YOU WILL SEIZE AND DESTROY... ALL MILITARY STORES... BUT YOU WILL TAKE CARE THAT THE SOLDIERS DO NOT PLUNDER THE INHABITANTS OR HURT PRIVATE PROPERTY.)]] Gage did not issue written orders for the arrest of rebel leaders, as he feared doing so might spark an uprising.[10]

Between 9 and 10 pm on the night of April 18, 1775, Joseph Warren told Revere and William Dawes that the king's troops were about to embark in boats from Boston bound for Cambridge and the road to Lexington and Concord. Warren's intelligence suggested that the most likely objectives of the regulars' movements later that night would be the capture of Adams and Hancock. They did not worry about the possibility of regulars marching to Concord, since the supplies at Concord were safe, but they did think their leaders in Lexington were unaware of the potential danger that night. Revere and Dawes were sent out to warn them and to alert colonial militias in nearby towns.[11][12]

In the days before April 18, Revere had instructed Robert Newman, the sexton of the Old North Church, to send a signal by lantern to alert colonists in Charlestown as to the movements of the troops when the information became known. In what is well known today by the phrase (QONE IF BY LAND, TWO IF BY SEA), one lantern in the steeple would signal the army's choice of the land route, while two lanterns would signal the route (QBY WATER) across the Charles River.[13] Revere first gave instructions to send the signal to Charlestown. He then crossed the Charles River by rowboat, slipping past the British warship HMS Somerset at anchor. Crossings were banned at that hour, but Revere safely landed in Charlestown and rode to Lexington, avoiding a British patrol and later warning almost every house along the route. The Charlestown colonists dispatched additional riders to the north.[12][14]

Riding through present-day Somerville, Medford, and Arlington, Revere warned patriots along his route — many of whom set out on horseback to deliver warnings of their own. By the end of the night there were probably as many as 40 riders throughout Middlesex County carrying the news of the army's advance. Revere did not shout the phrase later attributed to him ("The British are coming!"), largely because the mission depended on secrecy and the countryside was filled with British army patrols, and because the colonists themselves were British.[15] Revere's warning, according to eyewitness accounts of the ride and Revere's own descriptions, was "The Regulars are coming out."[16] Revere arrived in Lexington around midnight, with Dawes arriving about a half hour later. They met with Samuel Adams and John Hancock, who were spending the night with Hancock's relatives (in what is now called the Hancock-Clarke House), and they spent a great deal of time discussing plans of action upon receiving the news. They believed that the forces leaving the city were too large for the sole task of arresting two men and that Concord was the main target.[17] The Lexington men dispatched riders to the surrounding towns, and Revere and Dawes continued along the road to Concord accompanied by Samuel Prescott, a doctor who happened to be in Lexington "returning from a lady friend's house at the awkward hour of 1 a.m."[12][18]

Revere, Dawes, and Prescott were detained by a British Army patrol in Lincoln at a roadblock on the way to Concord.[12] Prescott jumped his horse over a wall and escaped into the woods; he eventually reached Concord. Dawes also escaped, though he fell off his horse not long after and did not complete the ride.[19][20]

Revere was questioned by the British officers and told them of the army's movement from Boston, and that British army troops might be in some danger if they approached Lexington, because of the large number of hostile militia gathered there.[21] He and other captives taken by the patrol were then escorted east toward Lexington, until the sound of musket fire from the town center alarmed the patrolmen. Revere explained to them that it was probably an arriving militia company that had fired a volley upon its arrival. The sound was followed not long after by the pealing of the town bell.[22] The British confiscated Revere's horse, and rode off to warn the approaching army column. Revere was horseless and walked through a cemetery and pastures until he came to Rev. Clarke's house where Hancock and Adams were staying. As the battle on Lexington Green continued, Revere helped John Hancock and his family escape from Lexington with their possessions, including a trunk of Hancock's papers.[20]

The ride of the three men triggered a flexible system of (QALARM AND MUSTER) that had been carefully developed months before, in reaction to the colonists' impotent response to the Powder Alarm of September 1774. This system was an improved version of an old network of widespread notification and fast deployment of local militia forces in times of emergency. The colonists had periodically used this system all the way back to the early years of Indian wars in the colony, before it fell into disuse in the French and Indian War. In addition to other express riders delivering messages, bells, drums, alarm guns, bonfires and a trumpet were used for rapid communication from town to town, notifying the rebels in dozens of eastern Massachusetts villages that they should muster their militias because the regulars in numbers greater than 500 were leaving Boston, with possible hostile intentions. This system was so effective that people in towns 25 miles (40 km) from Boston were aware of the army's movements while they were still unloading boats in Cambridge.[23] Unlike in the Powder Alarm, the alarm raised by the three riders successfully allowed the militia to repel the British troops in Concord, after which the British were harried by the growing colonial militia all the way back to Boston.

In 1861, over 40 years after his death, the ride became the subject of "Paul Revere's Ride", a poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Its opening lines are:

Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-Five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year

Today, parts of the ride are posted with signs marked "Revere's Ride." The full ride used Main Street in Charlestown, Broadway and Main Street in Somerville, Main Street and High Street in Medford, to Arlington center, and Massachusetts Avenue the rest of the way (an old alignment through Arlington Heights is called "Paul Revere Road").

War years

At the beginning of the war, when Boston was occupied by the British army and most supporters of independence were evacuated, Revere and his family lived across the river in Watertown. In 1775, Revere was sent by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress to Philadelphia to study the working of the only powder mill in the colonies. Upon his arrival in Philadelphia he met with Robert Morris and John Dickinson who provided him with the following letter to present to Oswald Eve:

Sir

Philada. Novr. 21st 1775

I am requested by some Honorable Members of the Congress to recommend the bearer hereof Mr. Paul Revere to you. He is just arrived from New England where it is discovered they can manufacture a good deal of Salt Petre in Consequence of which they desire to Erect a Powder Mill & Mr. Revere has been pitched upon to gain instruction & Knowledge in this branch. A Powder Mill in New England cannot in the least degree affect your Manufacture nor be of any disadvantage to you. Therefore these Gentn & myself hope You will Chearfully & from Public Spirited Motives give Mr. Revere such information as will inable him to Conduct the business on his return home. I shall be glad of any opportunity to approve myself.

Sir Your very Obed Servt. Robt Morris

P.S. Mr. Revere will desire to see the Construction of your Mill & I hope you will gratify him in that point.

Sir, I heartily join with Mr. Morris in his Request; and am with great Respect, Your very hble Servt. John Dickinson[24]

Mr. Eve complied with the letter completely and allowed Revere to pass through the building to obtain sufficient information, which enabled him to set up a powder mill at Canton.[25]

Upon returning to Boston in 1776, Revere was commissioned a Major of infantry in the Massachusetts militia in April of that year. In November he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel of artillery, and was stationed at Castle William, defending Boston harbor, finally receiving command of this fort. He served in an expedition to Rhode Island in 1778, and in the following year participated in the disastrous Penobscot Expedition. Revere and his troops saw little action at this post, but they did participate in minor expeditions to Newport, Rhode Island and Worcester. Revere's rather undistinguished military career ended with the failed Penobscot expedition. After his return he was accused of having disobeyed the orders of one of his commanding officers, and dismissed from the militia. Revere returned to his businesses at that time, but was later cleared of the charges by a court-martial.

Revere's friend and compatriot Joseph Warren was killed during the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775. As soldiers killed in battle were often buried in mass graves without ceremony, Warren's grave was unmarked. On March 17, 1776, after the British army left Boston, Warren's brothers and a few friends went to the battlefield and found a grave containing two bodies.[26] After being buried for ten months, Warren's face was unrecognizable, but Revere was able to identify Warren's body because he had placed a false tooth in Warren's mouth, and recognized the wire he had used for fastening it.[27] Warren was given a proper funeral and reburied in a marked grave.

Later years

After the war, finding the silver trade difficult in the ensuing depression, Revere opened a hardware and home goods store and later became interested in metal work beyond gold and silver. By 1788 he had opened an iron and brass foundry in Boston's North End. As a foundryman he recognized a burgeoning market for church bells in the religious revival known as the Second Great Awakening that followed the war. He became one of the best-known metal casters of that instrument, working with sons Paul Jr. and Joseph Warren in the firm Paul Revere & Sons. This firm cast the first bell made in Boston and ultimately produced more than 900 bells. A substantial part of the foundry's business came from supplying shipyards with iron bolts and fittings for ship construction. In 1801 Revere became a pioneer in the production of copper plating, opening North America's first copper mill south of Boston in Canton, near the Canton Viaduct. Copper from the Revere Copper Company was used to cover the original wooden dome of the Massachusetts State House in 1802.

His business plans in the late 1780s were stymied by a shortage of adequate money in circulation. His plans rested on his entrepreneurial role as a manufacturer of cast iron, brass, and copper products. Alexander Hamilton's national policies regarding banks and industrialization exactly matched his dreams, and he became an ardent Federalist committed to building a robust economy and a powerful nation. His copper and brass works eventually grew, through sale and corporate merger, into a large national corporation, Revere Copper and Brass, Inc.

Revere died on May 10, 1818, at the age of 83, at his home on Charter Street in Boston. He is buried in the Old Granary Burying Ground on Tremont Street.

Paul Revere appears on the $5,000 Series EE Savings Bond issued by the United States Government.[28] The copper works he founded in 1801 continues as the Revere Copper Company, with manufacturing divisions in Rome, New York and New Bedford, Massachusetts.[29]

His original silverware, engravings, and other works are highly regarded today and can be found on display at prominent museums such as the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.[30]

Places and institutions named after Paul Revere

- Revere, Massachusetts, named 1871

- Paul Revere Village in Karlsruhe, Germany, former US Army residence, 1951

- Paul Revere Village, a townhouse condominium in Millbury, Massachusetts, founded 1984

- Paul Revere Village, a townhouse condominium in Canton, Massachusetts, founded 1998

- Paul Revere Middle School, Los Angeles, California, opened 1955

See also

- Johnny Tremain, 1943 children's novel by Esther Forbes set in Boston prior to and during the outbreak of the Revolution.

- Laura Secord, "Canada's Paul Revere"

- Israel Bissell

Notes

- ^ Revere's date of baptism is confused by the conversion between the Julian and Gregorian calendars, which offsets the date by 10 days. While the baptism was recorded on December 22, adjusting for the conversion between Julian and Gregorian calendars changes the date to January 1.

- ^ The History Channel, Mysteries of the Freemasons: America, video documentary, August 1, 2006, written by Noah Nicholas and Molly Bedell

- ^ Cumming, William P. (1975). The Fate of a Nation: The American Revolution Through Contemporary Eyes. New York: Phaidon Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-714-81644-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Martello, Robert (September 27, 2010). Midnight Ride, Industrial Dawn: Paul Revere and the Growth of American Enterprise. Studies in the History of Technology (1st ed.). The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 71–2. ISBN 978-0801897580.

- ^ Goss. Life of Colonel Paul Revere. Boston: Cupples, 1891.

- ^ Robinson, J Dennis (1997). "Paul Revere's Other Ride". NH: Seacoast. Retrieved 2009-06-13. The writer understates the distance from Boston to Portsmouth.

- ^ Fischer, Paul Revere's Ride, pp. 52–7.

- ^ Fischer, pp. 75–6.

- ^ Brooks, pp. 37–8.

- ^ Fischer, p. 85

- ^ Brooks, pp. 41–2.

- ^ a b c d Boatner, Mark Mayo III (May 1975) [1964]. Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (Bicentennial ed.). New York: David McKay. p. 622.

- ^ Watson, John Lee (1880). Paul Revere's Signal; The True Story of the Signal Lanterns in Christ Church, Boston. Trows Printing and Book Binding Company, Cornell University Library. p. 4. ISBN 978-1112125768.

- ^ Brooks, pp. 42–4.

- ^ Fischer, p. 110.

- ^ Paul Revere's Three Accounts of His Famous Ride, introduction by Edmund Morgan. Massachusetts Historical Society, 1961.

- ^ Brooks, p. 50.

- ^ John M. Murrin, et al. Liberty Equality Power: A History of the American People, Volume I: To 1877, third edition (Florence, Kentucky: Wadsworth-Thomson Learning, 1996, 2002), 205.

- ^ Fischer, pp. 131–2, 144.

- ^ a b Forbes, Esther (October 1, 1999). Paul Revere and the World He Lived in. Mariner Books. pp. 262–3. ISBN 978-0618001941.

- ^ Fischer, pp. 133–134

- ^ Fischer, pp. 135–6

- ^ Fischer, pp. 138–45.

- ^ Letters of Delegates to Congress: Volume 2 September 1775 - December 1775 --Robert Morris and John Dickinson to Oswell Eve, located in the Library of Congress

- ^ Petition of Oswell Eve, 22 March 1776, Papers of the Continental Congress, No. 42, II, f. 378 (microfilm, M247, reel 53, National Archives). As per footnotes in Patriot-improvers: Biographical Sketches of Members of the APS ...By Whitfield Jenks Bell

- ^ Boston 1775: Sumner letter

- ^ Charles Gettemy, "The True Story of Paul Revere, Chapter One: The Patriotic Engraver."

- ^ "U.S. Savings Bond Images". United States Treasury. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- ^ "About the Revere Copper Company". Revere Copper Company. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- ^ "Boston Museum of Fine Arts Search for Paul Revere". Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

References

- Brooks, Victor (1999). The Boston Campaign. Combined Publishing. ISBN 9780585234533.

- Fischer, David Hackett (1994). Paul Revere's Ride. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-508847-6. This book is extensively footnoted, and contains a voluminous list of primary resources concerning all aspects of these events.

- Esther Forbes, Paul Revere and the World He Lived In. Houghton Mifflin, 1942.

- Paul Revere, Artisan, Businessman and Patriot—The Man Behind the Myth. Paul Revere Memorial Association, 1988.

- Paul Revere's Three Accounts of His Famous Ride, introduction by Edmund Morgan. Massachusetts Historical Society, 1961.

- Edith J. Steblecki, Paul Revere and Freemasonry. PRMA, 1985.

- Jayne E. Triber, A True Republican: The Life of Paul Revere. U of Massachusetts Press, 1998.

- Robert Martello, Midnight Ride, Industrial Dawn: Paul Revere and the Growth of American Enterprise (Johns Hopkins Studies in the History of Technology). The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1 edition (September 27, 2010)

External links

- An interactive map showing the routes taken by Revere, Dawes, and Prescott is available at The Paul Revere House website

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Paul Revere Heritage Project

- The Paul Revere House

- Revere Rolling Mill (about the endangered original Revere copper works site in Canton, MA)

- Original copper engravings and other documents in collections of the Massachusetts State Archives

- American businesspeople

- American engravers

- American people of French descent

- American Revolution spies

- American silversmiths

- American Unitarians

- Foundrymen

- Massachusetts Federalists

- Massachusetts militiamen in the American Revolution

- Patriots in the American Revolution

- People from Boston, Massachusetts

- People of Massachusetts in the American Revolution

- 1734 births

- 1818 deaths

- 18th-century people