Pythagorean theorem

In mathematics, the Pythagorean theorem (AmE) or Pythagoras' theorem (BrE) is a relation in Euclidean geometry among the three sides of a right triangle. The theorem is named after the Greek mathematician Pythagoras, who by tradition is credited with its discovery and proof,[1] although knowledge of the theorem almost certainly predates him.

The theorem is as follows:

In any right triangle, the area of the square whose side is the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right angle) is equal to the sum of the areas of the squares whose sides are the two legs (the two sides that meet at a right angle).

This is usually summarized as:

The square on the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares on the other two sides.

If we let c be the length of the hypotenuse and a and b be the lengths of the other two sides, the theorem can be expressed as the equation

or, solved for c:

This equation provides a simple relation among the three sides of a right triangle so that if the lengths of any two sides are known, the length of the third side can be found. A generalization of this theorem is the law of cosines, which allows the computation of the length of the third side of any triangle, given the lengths of two sides and the size of the angle between them. If the angle between the sides is a right angle it reduces to the Pythagorean theorem.

| Trigonometry |

|---|

|

| Reference |

| Laws and theorems |

| Calculus |

| Mathematicians |

History

The history of the theorem can be divided into three parts: knowledge of Pythagorean triples, knowledge of the relationship between the sides of a right triangle, and proofs of the theorem.

Megalithic monuments from circa 2500 BC in Egypt, and in the British Isles, incorporate right triangles with integer sides.[2] Bartel Leendert van der Waerden conjectures that these Pythagorean triples were discovered algebraically.[3]

Written between 2000–1786 BC, the Middle Kingdom Egyptian papyrus Berlin 6619 includes a problem whose solution is a Pythagorean triple.

During the reign of Hammurabi, the Mesopotamian tablet Plimpton 322, written between 1790 and 1750 BC, contains many entries closely related to Pythagorean triples.

The Baudhayana Sulba Sutra, the dates of which are given variously as between the 8th century BCE and the 2nd century BCE, in India, contains a list of Pythagorean triples discovered algebraically, a statement of the Pythagorean theorem, and a geometrical proof of the Pythagorean theorem for an isosceles right triangle.

The Apastamba Sulba Sutra (circa 600 BC) contains a numerical proof of the general Pythagorean theorem, using an area computation. Van der Waerden believes that "it was certainly based on earlier traditions". According to Albert Bŭrk, this is the original proof of the theorem; he further theorizes that Pythagoras visited Arakonam, India, and copied it.

Pythagoras, whose dates are commonly given as 569–475 BC, used algebraic methods to construct Pythagorean triples, according to Proklos's commentary on Euclid. Proklos, however, wrote between 410 and 485 AD. According to Sir Thomas L. Heath, there is no attribution of the theorem to Pythagoras for five centuries after Pythagoras lived. However, when authors such as Plutarch and Cicero attributed the theorem to Pythagoras, they did so in a way which suggests that the attribution was widely known and undoubted.

Around 400 BC, according to Proklos, Plato gave a method for finding Pythagorean triples that combined algebra and geometry. Circa 300 BC, in Euclid's Elements, the oldest extant axiomatic proof of the theorem is presented.

Written sometime between 500 BC and 200 AD, the Chinese text Chou Pei Suan Ching (周髀算经), (The Arithmetical Classic of the Gnomon and the Circular Paths of Heaven) gives a visual proof of the Pythagorean theorem — in China it is called the "Gougu Theorem" (勾股定理) — for the (3, 4, 5) triangle. During the Han Dynasty, from 202 BC to 220 AD, Pythagorean triples appear in The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art, together with a mention of right triangles.[4]

The first recorded use is in China, known as the "Gougu theorem" (勾股定理) and in India known as the Bhaskara Theorem.

There is much debate on whether the Pythagorean theorem was discovered once or many times. Boyer (1991) thinks the elements found in the Shulba Sutras may be of Mesopotamian derivation.[5]

Proofs

This theorem may have more known proofs than any other (the law of quadratic reciprocity being also a contender for that distinction); the book Pythagorean Proposition, by Elisha Scott Loomis, contains 367 proofs.

Some arguments based on trigonometric identities (such as Taylor series for sine and cosine) have been proposed as proofs for the theorem. However, since all the fundamental trigonometric identities are proved using the Pythagorean theorem, there cannot be any trigonometric proof. (See also begging the question.)

Proof using similar triangles

Like many of the proofs of the Pythagorean theorem, this one is based on the proportionality of the sides of two similar triangles.

Let ABC represent a right triangle, with the right angle located at C, as shown on the figure. We draw the altitude from point C, and call H its intersection with the side AB. The new triangle ACH is similar to our triangle ABC, because they both have a right angle (by definition of the altitude), and they share the angle at A, meaning that the third angle will be the same in both triangles as well. By a similar reasoning, the triangle CBH is also similar to ABC. The similarities lead to the two ratios..:

As

so

These can be written as

Summing these two equalities, we obtain

In other words, the Pythagorean theorem:

Euclid's proof

In Euclid's Elements, Proposition 47 of Book 1, the Pythagorean theorem is proved by an argument along the following lines. Let A, B, C be the vertices of a right triangle, with a right angle at A. Drop a perpendicular from A to the side opposite the hypotenuse in the square on the hypotenuse. That line divides the square on the hypotenuse into two rectangles, each having the same area as one of the two squares on the legs.

For the formal proof, we require four elementary lemmata:

- If two triangles have two sides of the one equal to two sides of the other, each to each, and the angles included by those sides equal, then the triangles are congruent.

- The area of a triangle is half the area of any parallelogram on the same base and having the same altitude.

- The area of any square is equal to the product of two of its sides.

- The area of any rectangle is equal to the product of two adjacent sides (follows from Lemma 3).

The intuitive idea behind this proof, which can make it easier to follow, is that the top squares are morphed into parallelograms with the same size, then turned and morphed into the left and right rectangles in the lower square, again at constant area.

The proof is as follows:

- Let ABC be a right-angled triangle with right angle CAB.

- On each of the sides BC, AB, and CA, squares are drawn, CBDE, BAGF, and ACIH, in that order.

- From A, draw a line parallel to BD and CE. It will perpendicularly intersect BC and DE at K and L, respectively.

- Join CF and AD, to form the triangles BCF and BDA.

- Angles CAB and BAG are both right angles; therefore C, A, and G are colinear. Similarly for B, A, and H.

- Angles CBD and FBA are both right angles; therefore angle ABD equals angle FBC, since both are the sum of a right angle and angle ABC.

- Since AB and BD are equal to FB and BC, respectively, triangle ABD must be equal to triangle FBC.

- Since A is colinear with K and L, rectangle BDLK must be twice in area to triangle ABD.

- Since C is colinear with A and G, square BAGF must be twice in area to triangle FBC.

- Therefore rectangle BDLK must have the same area as square BAGF = AB2.

- Similarly, it can be shown that rectangle CKLE must have the same area as square ACIH = AC2.

- Adding these two results, AB2 + AC2 = BD*BK + KL*KC

- Since BD = KL, BD*BK + KL*KC = BD(BK + KC) = BD*BC

- Therefore AB2 + AC2 = BC2, since CBDE is a square.

This proof appears in Euclid's Elements as that of Proposition 1.47.[6]

Garfield's proof

James A. Garfield (later President of the United States) is credited with a novel algebraic proof using a trapezoid containing two examples of the triangle[[1]], the figure comprising one-half of the figure using four triangles enclosing a square shown below.

Similarity proof

From the same diagram as that in Euclid's proof above, we can see three similar figures, each being "a square with a triangle on top". Since the large triangle is made of the two smaller triangles, its area is the sum of areas of the two smaller ones. By similarity, the three squares are in the same proportions relative to each other as the three triangles, and so likewise the area of the larger square is the sum of the areas of the two smaller squares.

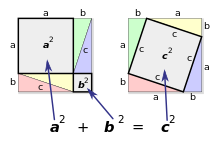

Proof by rearrangement

A proof by rearrangement is given by the illustration and the animation. In the illustration, the area of each large square is (a + b)². In both, the area of four identical triangles is removed. The remaining areas, a² + b² and c², are equal. Q.E.D.

This proof is indeed very simple, but it is not elementary, in the sense that it does not depend solely upon the most basic axioms and theorems of Euclidean geometry. In particular, while it is quite easy to give a formula for area of triangles and squares, it is not as easy to prove that the area of a square is the sum of areas of its pieces. In fact, proving the necessary properties is harder than proving the Pythagorean theorem itself (see Lebesgue measure and Banach-Tarski paradox). Actually, this difficulty affects all simple Euclidean proofs involving area; for instance, deriving the area of a right triangle involves the assumption that it is half the area of a rectangle with the same height and base. For this reason, axiomatic introductions to geometry usually employ another proof based on the similarity of triangles (see above).

A second graphic illustration of the Pythagorean theorem (in yellow and blue to the left) fits parts of the sides' squares into the hypotenuse's square. A related proof would show that the repositioned parts are identical with the originals and, since the sum of equals are equal, that the corresponding areas are equal. To show that a square is the result one must show that the length of the new sides equals c. Note that for this proof to work, one must provide a way to handle cutting the small square in more and more slices as the corresponding side gets smaller and smaller.[7]

Algebraic proof

An algebraic variant of this proof is provided by the following reasoning. Looking at the illustration which is a large square with identical right triangles in its corners, the area of each of these four triangles is given by an angle corresponding with the side of length C.

The A-side angle and B-side angle of each of these triangles are complementary angles, so each of the angles of the blue area in the middle is a right angle, making this area a square with side length C. The area of this square is C2. Thus the area of everything together is given by:

However, as the large square has sides of length A + B, we can also calculate its area as (A + B)2, which expands to A2 + 2AB + B2.

- (Distribution of the 4)

- (Subtraction of 2AB)

Proof by differential equations

One can arrive at the Pythagorean theorem by studying how changes in a side produce a change in the hypotenuse in the following diagram and employing a little calculus.[8]

As a result of a change in side a,

by similar triangles and for differential changes. So

upon separation of variables. A more general result is

which results from adding a second term for changes in side b.

Integrating gives

So

As can be seen, the squares are due to the particular proportion between the changes and the sides while the sum is a result of the independent contributions of the changes in the sides which is not evident from the geometric proofs. From the proportion given it can be shown that the changes in the sides are inversely proportional to the sides. The differential equation suggests that the theorem is due to relative changes and its derivation is nearly equivalent to computing a line integral. A simpler derivation would leave fixed and then observe that

It is doubtful that the Pythagoreans would have been able to do the above proof but they knew how to compute the area of a triangle and were familiar with figurate numbers and the gnomon, a segment added onto a geometrical figure. All of these ideas predate calculus and are an alternative for the integral.

The proportional relation between the changes and their sides is at best an approximation, so how can one justify its use? The answer is the approximation gets better for smaller changes since the arc of the circle which cuts off more closely approaches the tangent to the circle. As for the sides and triangles, no matter how many segments they are divided into the sum of these segments is always the same. The Pythagoreans were trying to understand change and motion and this led them to realize that the number line was infinitely divisible. Could they have discovered the approximation for the changes in the sides? One only has to observe that the motion of the shadow of a sundial produces the hypotenuses of the triangles to derive the figure shown.

Rational trigonometry

For a proof by the methods of rational trigonometry, see Pythagorean theorem proof (rational trigonometry).

Converse

The converse of the theorem is also true:

For any three positive numbers a, b, and c such that a2 + b2 = c2, there exists a triangle with sides a, b and c, and every such triangle has a right angle between the sides of lengths a and b.

This converse also appears in Euclid's Elements. It can be proven using the law of cosines (see below under Generalizations), or by the following proof:

Let ABC be a triangle with side lengths a, b, and c, with a2 + b2 = c2. We need to prove that the angle between the a and b sides is a right angle. We construct another triangle with a right angle between sides of lengths a and b. By the Pythagorean theorem, it follows that the hypotenuse of this triangle also has length c. Since both triangles have the same side lengths a, b and c, they are congruent, and so they must have the same angles. Therefore, the angle between the side of lengths a and b in our original triangle is a right angle.

A corollary of the Pythagorean theorem's converse is a simple means of determining whether a triangle is right, obtuse, or acute, as follows. Where c is chosen to be the longest of the three sides:

- If a2 + b2 = c2, then the triangle is right.

- If a2 + b2 > c2, then the triangle is acute.

- If a2 + b2 < c2, then the triangle is obtuse.

Consequences and uses of the theorem

Pythagorean triples

A Pythagorean triple consists of three positive integers a, b, and c, such that . In other words, a Pythagorean triple represents the lengths of the sides of a right triangle where all three sides have integer lengths. Evidence from megalithic monuments on the British Isles shows that such triples were known before the discovery of writing. Such a triple is commonly written (a, b, c), some well-known examples are (3, 4, 5) and (5, 12, 13).

The existence of irrational numbers

One of the consequences of the Pythagorean theorem is that irrational numbers, such as the square root of two, can be constructed. A right triangle with legs both equal to one unit has hypotenuse length square root of two. The Pythagoreans proved that the square root of two is irrational, and this proof has come down to us even though it flew in the face of their cherished belief that everything was rational. According to the legend, Hippasus, who first proved the irrationality of the square root of two, was drowned at sea as a consequence.[9]

Distance in Cartesian coordinates

The distance formula in Cartesian coordinates is derived from the Pythagorean theorem. If (x0, y0) and (x1, y1) are points in the plane, then the distance between them, also called the Euclidean distance, is given by

More generally, in Euclidean n-space, the Euclidean distance between two points, and , is defined, using the Pythagorean theorem, as:

Generalizations

The Pythagorean theorem was generalised by Euclid in his Elements:

If one erects similar figures (see Euclidean geometry) on the sides of a right triangle, then the sum of the areas of the two smaller ones equals the area of the larger one.

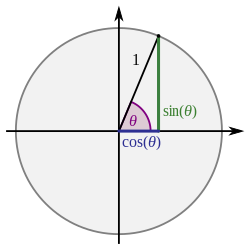

The Pythagorean theorem is a special case of the more general theorem relating the lengths of sides in any triangle, the law of cosines:

- where θ is the angle between sides a and b.

- When θ is 90 degrees, then cos(θ) = 0, so the formula reduces to the usual Pythagorean theorem.

Given two vectors v and w in a complex inner product space, the Pythagorean theorem takes the following form:

In particular, ||v + w||2 = ||v||2 + ||w||2 if and only if v and w are orthogonal.

Using mathematical induction, the previous result can be extended to any finite number of pairwise orthogonal vectors. Let v1, v2,…, vn be vectors in an inner product space such that <vi, vj> = 0 for 1 ≤ i < j ≤ n. Then

The generalization of this result to infinite-dimensional real inner product spaces is known as Parseval's identity.

When the theorem above about vectors is rewritten in terms of solid geometry, it becomes the following theorem. If lines AB and BC form a right angle at B, and lines BC and CD form a right angle at C, and if CD is perpendicular to the plane containing lines AB and BC, then the sum of the squares of the lengths of AB, BC, and CD is equal to the square of AD. The proof is trivial.

Another generalization of the Pythagorean theorem to three dimensions is de Gua's theorem, named for Jean Paul de Gua de Malves: If a tetrahedron has a right angle corner (a corner like a cube), then the square of the area of the face opposite the right angle corner is the sum of the squares of the areas of the other three faces.

There are also analogs of these theorems in dimensions four and higher.

In a triangle with three acute angles, α + β > γ holds. Therefore, a2 + b2 > c2 holds.

In a triangle with an obtuse angle, α + β < γ holds. Therefore, a2 + b2 < c2 holds.

Edsger Dijkstra has stated this proposition about acute, right, and obtuse triangles in this language:

where α is the angle opposite to side a, β is the angle opposite to side b and γ is the angle opposite to side c.[10]

The Pythagorean theorem in non-Euclidean geometry

The Pythagorean theorem is derived from the axioms of Euclidean geometry, and in fact, the Euclidean form of the Pythagorean theorem given above does not hold in non-Euclidean geometry. (It has been shown in fact to be equivalent to Euclid's Parallel (Fifth) Postulate.) For example, in spherical geometry, all three sides of the right triangle bounding an octant of the unit sphere have length equal to ; this violates the Euclidean Pythagorean theorem because .

This means that in non-Euclidean geometry, the Pythagorean theorem must necessarily take a different form from the Euclidean theorem. There are two cases to consider — spherical geometry and hyperbolic plane geometry; in each case, as in the Euclidean case, the result follows from the appropriate law of cosines:

For any right triangle on a sphere of radius R, the Pythagorean theorem takes the form

By using the Maclaurin series for the cosine function, it can be shown that as the radius R approaches infinity, the spherical form of the Pythagorean theorem approaches the Euclidean form.

For any triangle in the hyperbolic plane (with Gaussian curvature −1), the Pythagorean theorem takes the form

where cosh is the hyperbolic cosine.

By using the Maclaurin series for this function, it can be shown that as a hyperbolic triangle becomes very small (i.e., as a, b, and c all approach zero), the hyperbolic form of the Pythagorean theorem approaches the Euclidean form.

In hyperbolic geometry, for a right triangle one can also write,

where is the angle of parallelism of the line segment AB that where μ is the multiplicative distance function (see Hilbert's arithmetic of ends).

In hyperbolic trigonometry, the sine of the angle of parallelism satisfies

Thus, the equation takes the form

where a, b, and c are multiplicative distances of the sides of the right triangle (Hartshorne, 2000).

Cultural references to the Pythagorean theorem

- In The Wizard of Oz, when the Scarecrow receives his diploma from the Wizard, he immediately exhibits his "knowledge" by reciting a mangled and incorrect version of the theorem: "The sum of the square roots of any two sides of an isosceles triangle is equal to the square root of the remaining side. Oh, joy, oh, rapture. I've got a brain!" The "knowledge" exhibited by the Scarecrow is incorrect. The accurate statement would have been "The sum of the squares of the legs of a right triangle is equal to the square of the remaining side."[11]

- In an episode of The Simpsons, Homer quotes the Oz Scarecrow's quote, thus turning the theorem into a cultural reference to a cultural reference. After finding a pair of Henry Kissinger's glasses in a toilet at the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant, Homer puts them on and quotes the scarecrow's mangled formula. A man in a nearby toilet stall then yells out "That's a right triangle, you idiot!" (The comment about square roots remained uncorrected.)

- In the English version of the seventeenth Asterix book "The Mansions of the Gods", Julius Caesar uses the services of an architect named "Squaronthehypotenus" to develop the estate near the village, through which he hopes to absorb the Gaulish village into the Roman culture.

- In 2000, Uganda released a coin with the shape of a right triangle. The tail has an image of Pythagoras and the Pythagorean theorem, accompanied with the mention "Pythagoras Millennium".[12]

- In the Major-General's Song, "About binomial theorem I'm teeming with a lot o' news, With many cheerful facts about the square of the hypotenuse."

- Greece, Japan, San Marino, Sierra Leone, and Surinam have issued postage stamps depicting Pythagoras and the Pythagorean theorem.[13]

- In South Park, Eric Cartman shows the Pythagorean theorem during a slide show at show and tell.

See also

Notes

- ^ Heath, Vol I, p. 144.

- ^ "Megalithic Monuments".

- ^ van der Waerden 1983.

- ^ Swetz.

- ^ Boyer (1991). "China and India". p. 207.

we find rules for the construction of right angles by means of triples of cords the lengths of which form Pythagorean triages, such as 3, 4, and 5, or 5, 12, and 13, or 8, 15, and 17, or 12, 35, and 37. However all of these triads are easily derived from the old Babylonian rule; hence, Mesopotamian influence in the Sulvasutras is not unlikely. Aspastamba knew that the square on the diagonal of a rectangle is equal to the sum of the squares on the two adjacent sides, but this form of the Pythagorean theorem also may have been derived from Mesopotamia. [...] So conjectural are the origin and period of the Sulbasutras that we cannot tell whether or not the rules are related to early Egyptian surveying or to the later Greek problem of alter doubling. They are variously dated within an interval of almost a thousand years stretching from the eighth century B.C. to the second century of our era.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Elements 1.47 by Euclid, retrieved 19 December 2006

- ^ Pythagorean Theorem: Subtle Dangers of Visual Proof by Alexander Bogomolny, retrieved 19 December 2006.

- ^ Hardy.

- ^ Heath, Vol I, pp. 65, 154; Stillwell, p. 8–9.

- ^ "Dijkstra's generalization" (PDF).

- ^ "The Scarecrow's Formula".

- ^ "Le Saviez-vous ?".

- ^ Miller, Jeff (2007-08-03). "Images of Mathematicians on Postage Stamps". Retrieved 2007-08-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

References

- Bell, John L., The Art of the Intelligible: An Elementary Survey of Mathematics in its Conceptual Development, Kluwer, 1999. ISBN 0-7923-5972-0.

- Euclid, The Elements, Translated with an introduction and commentary by Sir Thomas L. Heath, Dover, (3 vols.), 2nd edition, 1956.

- Hardy, Michael, "Pythagoras Made Difficult". Mathematical Intelligencer, 10 (3), p. 31, 1988.

- Heath, Sir Thomas, A History of Greek Mathematics (2 Vols.), Clarendon Press, Oxford (1921), Dover Publications, Inc. (1981), ISBN 0-486-24073-8.

- Loomis, Elisha Scott, The Pythagorean proposition. 2nd edition, Washington, D.C : The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 1968.

- Maor, Eli, The Pythagorean Theorem: A 4,000-Year History. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-691-12526-8.

- Stillwell, John, Mathematics and Its History, Springer-Verlag, 1989. ISBN 0-387-96981-0 and ISBN 3-540-96981-0.

- Swetz, Frank, Kao, T. I., Was Pythagoras Chinese?: An Examination of Right Triangle Theory in Ancient China, Pennsylvania State University Press. 1977.

- van der Waerden, B.L., Geometry and Algebra in Ancient Civilizations, Springer, 1983.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Pythagorean theorem". MathWorld.

- Proof of the Pythagorean theorem

- Pythagorean theorem with interactive animation

- Pythagorean Theorem (more than 70 proofs from cut-the-knot)

- FORTRAN code for solving with the Pythagorean theorem