William Bradford (governor)

William Bradford | |

|---|---|

"Embarkation of the Pilgrims," by Robert Walter Weir. William Bradford is depicted at center, kneeling in the background, symbolically behind Gov. John Carver (holding hat) whom Bradford would succeed.[1] | |

| 2nd, 5th, 7th, 9th & 11th Governor of Plymouth Colony | |

| In office 1621 – 1633 1635–1636 1637–1638 1639–1644 1645–1657 | |

| Preceded by | John Carver (1621) Thomas Prence (1635) Edward Winslow (1637) Thomas Prence (1639) Edward Winslow (1645) |

| Succeeded by | Edward Winslow (1633) Edward Winslow (1636) Thomas Prence (1638) Edward Winslow (1644) Thomas Prence (1645) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 240px March 19, 1590 Austerfield, Yorkshire, England |

| Died | May 9, 1657 (aged 67) Plymouth, Plymouth Colony |

| Resting place | Burial Hill, Plymouth, Massachusetts |

| Spouse(s) | Dorothy Bradford Alice Carpenter |

| Parent |

|

| Profession | Weaver |

William Bradford (March 19, 1590 – May 9, 1657) was an English leader of the settlers of the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts, and served as governor for over 30 years after John Carver died. His journal (1620–1647) was published as Of Plymouth Plantation. Bradford is credited as the first civil authority to designate what popular American culture now views as Thanksgiving in the United States.[2]

Early life

Childhood

William Bradford was born to William and Alice Bradford in Austerfield, Yorkshire, England in 1590.[3] Austerfield was a small town of approximately 200, most of them farmers of modest means.[4] The Bradford family, owning a large farm, was considered comparatively wealthy and influential among the citizens of Austerfield.[5]

As a child, Bradford experienced the loss of numerous family members. Some historians, such as Nathaniel Philbrick, noted that Bradford’s lack of family bonds was a significant factor in his joining the dissident religious congregation that would one day be known as the Pilgrims.[6] When Bradford was just over a year old, his father died. He was raised by his mother until the age of four when his mother re-married and Bradford was sent to live with his grandfather.[3] Two years later, his grandfather died and he returned to live with his mother and stepfather. A year later, in 1597, Bradford became an orphan at age 7 when his mother died. He was sent to live with two uncles.[3]

His uncles intended for young Bradford to help them on their farm, however Bradford (he later claimed in his journal) suffered at this time from a "long sickness" and was unable to do much work. He instead turned to reading, becoming familiar with the Bible and classic works of literature. This, too, was a key factor in his intellectual curiosity and his eventual attraction to the Separatists.[7]

Separatist congregation

When Bradford was 12 years old, a young friend invited him to hear the Rev. Richard Clyfton preach 10 miles away in Babworth. Clyfton was a Puritan minister who believed that the Church of England required strict reforms to eliminate all vestiges of Catholic practices. This would, proponents believed, result in a more "pure" Christian church. Bradford was immediately inspired by Clyfton’s preachings.[8]

Although he was forbidden to do so by his uncles, Bradford continued to attend Clyfton’s sermons. During one of these meetings he met and befriended William Brewster, bailiff and postmaster for the Archbishop of York. Brewster, 24 years older than Bradford, became a father figure to the young man.[9] He resided at Scrooby Manor, just four miles from Austerfield. During frequent visits, Bradford borrowed books from Brewster and Brewster told the young man about church reform efforts taking place throughout England.[9]

King James I took the English throne in 1603 and declared that he would put an end to church reform and deal harshly with radical critics of the Church of England.[10] By 1607, a group of about 50 reform-minded individuals began meeting secretly at Scrooby Manor to celebrate the Sabbath, led by Richard Clyfton and also Rev. John Robinson. This group soon decided that reform of the Church of England was hopeless and that they would separate all ties with it. Thus they became known as Separatists.

The weekly meetings of the Separatists soon attracted the attention of the Archbishop of York and many members of the congregation were arrested in 1607.[4] Brewster was found guilty of being "disobedient in matters of religion" and fined. Some members were imprisoned and others were watched, according to Bradford, "night and day" by those loyal to the archbishop.[4] Adding to their concerns, members of the Scrooby congregation learned that other Separatists in London had been imprisoned and left to starve.[11]

When the Scrooby congregation decided in 1607 to leave England illegally for the Dutch Republic (where religious freedom was permitted), William Bradford determined to go with them. The group encountered several major setbacks in trying to leave England, most notably their betrayal by an English sea captain who had agreed to bring the congregation to the Netherlands but instead turned them over to authorities.[12] Most of the congregation, including Bradford, were imprisoned for a short time after this failed attempt.[13] By the summer of 1608, however, the Scrooby congregation, including 18-year-old William Bradford, had managed to escape England in small groups and relocated in Amsterdam.

In the Dutch Republic

William Bradford arrived in Amsterdam in August 1608. Having no family with him, Bradford was taken in by the Brewster household. The Separatists, being foreigners and having spent most of their money in attempts to get to the Dutch Republic, had to work the lowest of jobs and lived in poor conditions. After nine months, the congregation chose to relocate to the smaller city of Leiden.[14]

Bradford continued to reside with the Brewster family in a poor Leiden neighborhood known as Stink Alley.[15] Conditions changed dramatically for Bradford, however, when he turned 21 and was able to claim his family inheritance in 1611. Bradford soon bought his own house, set up a workshop as a fustian weaver, and earned a reputable standing.[16]

In 1613, Bradford married Dorothy May, the daughter of a well-off English couple living in Amsterdam. The couple was married in a civil service, as the Separatists could find no example of a religious service in the Scriptures.[17] In 1617, the Bradfords had their first child, John Bradford.[18]

By 1617, the Scrooby congregation began to plan the establishment of their own colony in the New World.[19] Although the Separatists could practice religion as they pleased in the Dutch Republic, they were troubled by the fact that, after nearly ten years in the Netherlands, their children were being influenced by Dutch customs and language. Therefore, the Separatists commenced three years of difficult negotiations in England to seek permission to settle in the northern parts of the Colony of Virginia (which then extended north to what would eventually be known as the Hudson River).[20] The colonists also struggled to negotiate terms with a group of financial backers in London known as the Merchant Adventurers. By July 1620, Robert Cushman and John Carver had made the necessary arrangements and approximately fifty Separatists departed Delftshaven on board the Speedwell.[21]

It was an emotional departure. Many families were split as some Separatists stayed behind in the Netherlands, planning to make the voyage to the New World after the colony had been established. William and Dorothy Bradford left their three year old son John with Dorothy's parents in Amsterdam, possibly because he was too frail to make the voyage.[21]

Founding of Plymouth Colony

Voyage to New England

According to the arrangements made by Carver and Cushman, the Speedwell was to meet up with the Mayflower off the coast of England and both would sail to Hudson's River, now the site of New York City. The Speedwell, however, proved too leaky to make the voyage and about 100 passengers were instead crowded aboard the Mayflower. Joining the Scrooby congregation were about 50 colonists who had been recruited by the Merchant Adventurers for their vocational skills which would prove useful in establishing a colony.[22] These passengers of the Mayflower, both Separatist and non-Separatist, are commonly referred to today as "Pilgrims." The term is derived from a passage in Bradford's journal, written years later, describing their departure from the Netherlands:

...With mutual embraces and many tears, they took their leaves of one another, which proved to be the last leave to many of them...but they knew they were pilgrims and looked not much on those things, but lifted their eyes to heaven, their dearest country and quited their spirits...[23]

The Mayflower reached Cape Cod (now part of Massachusetts) on November 9, 1620 after a voyage of 64 days.[24] For a variety of reasons, primarily a shortage of supplies, the Mayflower could not proceed to Hudson's River and the colonists decided to settle somewhere on or near Cape Cod.[24] They had no permission from the Crown to do so, however, and the legal status of the colony would therefore become void. The leaders of the colony felt this situation might lead to political anarchy and, motivated by mutinous outbursts from some of the colonists, they drafted the Mayflower Compact off the coast of Cape Cod.[25] Through the compact, which all free adult males signed, the colonists agreed to majority rule. Simultaneously, they elected John Carver their first governor.[26]

Up to this time, Bradford, aged 30, had yet to assume any significant leadership role in the colony. When the Mayflower anchored in present-day Provincetown Harbor and the time came to search for a place for settlement, Bradford volunteered to be a member of the exploration parties.[27] In November and December, these parties made three separate ventures from the Mayflower on foot and by boat, finally locating what is now Plymouth harbor in mid December and selecting that site for settlement. During the first expedition on foot, Bradford was caught up in a deer trap made by Native Americans and hauled nearly upside down.[28] During the third exploration, which departed from the Mayflower on December 6, 1620, a group of men including Bradford located present day Plymouth Bay. A winter storm nearly sunk their boat as they approached the bay, but the explorers, suffering from severe exposure to the cold and waves, managed to successfully land on Clark's Island.[29]

During the ensuing days, they explored the bay and found a suitable place for settlement, now the site of downtown Plymouth, Massachusetts. The location featured a prominent hill (now known as Burial Hill) ideal for a defensive fort. There were numerous brooks providing fresh water. Also, the site had been the location of a Native American village known as Patuxet; therefore, much of the area had already been cleared for planting corn. The Patuxet tribe, between 1616 and 1619, had been wiped out by plagues resulting from contact with English fishermen—diseases to which the Patuxet had no immunity.[30] Bradford later wrote that bones of the dead were clearly evident in many places.[31]

Loss of first wife

The exploring party made their way back to the Mayflower to share the good news that a place for settlement had been found. When Bradford arrived back onboard, he learned of the death of his wife, Dorothy. The day after he had embarked with the exploring party, Dorothy slipped over the side of the Mayflower and drowned.[32]

Many historians, including Nathaniel Philbrick and Gary Schmidt, suggest that Dorothy may have committed suicide due to despair over her separation from her only son and fear of settling in a dangerous wilderness.[27][32] Bradford did not write about her death in his journal, and there are no indications that Bradford ever spoke of her again.[33] Some, including historian Kieran Doherty, suggest that Bradford's silence on the subject is an indication of his purported shame over her suicide.[33] There are no contemporary accounts to indicate whether her death was an accident or a suicide.[32]

Great sickness

The Mayflower arrived in Plymouth Bay on December 20, 1620. The settlers began building the colony's first house on December 23. Their efforts were slowed, however, when a widespread sickness struck the settlers.[34]

On January 11, 1621, as Bradford was helping to build houses, he was suddenly struck with great pain in his hipbone and he collapsed. Succumbing to the illness that had afflicted many others, Bradford was taken to the "common house" (the only finished house then built) and it was feared he would not last the night.[35]

During the epidemic, there were only a small number of men who remained healthy and bore the responsibility of caring for the sick. One of these was Captain Myles Standish, a soldier who had been hired by the settlers to coordinate the defense of the colony. Standish cared for Bradford during his illness and this was the beginning of a bond of friendship between the two men.[36] Bradford would soon be elected governor and, in that capacity, he would work closely with Standish. Bradford had no military experience and therefore would come to rely on and trust the Captain's advice on military matters.[37]

Bradford recovered; many of the settlers were not so fortunate. During the months of February and March 1621 sometimes two or three people died a day. By the end of the winter, half of the 100 settlers had died.[38] In an attempt to hide their weakness from Native Americans who might be watching them, the settlers buried their dead in unmarked graves on Cole's Hill and made efforts to conceal the burials.[39]

Early service as governor

On March 16, the settlers had their first meeting with the Native Americans who lived in the region when Samoset, a representative of Massasoit, the sachem of the Pokanoket, walked into the village of Plymouth. This soon led to a visit by Massasoit himself on March 22 during which the leader of the Pokanoket signed a treaty with John Carver, then Governor of Plymouth. The treaty declared an alliance between the Pokanoket and Plymouth and required the two parties to aid each other militarily in times of need.[40] Bradford recorded the language of the brief treaty in his journal. He would soon become governor and the clause of the treaty that would occupy much of his attention as governor pertained to mutual aid. It read, "If any did unjustly war against [Massasoit], we would aid him; if any did war against us, [Massasoit] should aid us."[41] This agreement, although it secured for the English a desperately needed ally in New England, would result in tensions between the English and Massasoit's rivals, such as the Narragansett and the Massachusett.[37] In April 1621, Governor Carver collapsed while working in the fields on a hot day. He died a few days later. The settlers of Plymouth then chose Bradford as the new governor. Bradford would remain in that position for most of his life.[42]

The elected leadership of Plymouth Colony at first consisted of a governor and an assistant governor. The assistant governor for the first three years of the colony's history was Isaac Allerton. In 1624, the structure was changed to a governor and five assistants who were referred to as the "court of assistants," "magistrates," or the "governor's council." These men advised the governor and had the right to vote on important matters of governance, helping Bradford in guiding the evolution of the colony and its improvised government.[43][44] Assistants during the early years of the colony included Thomas Prence, Stephen Hopkins, John Alden, and John Howland.[45]

Bradford suffered from a long, undisclosed illness during much of the winter of 1656-1657, and died one day following his prediction that he would soon expire.[46]

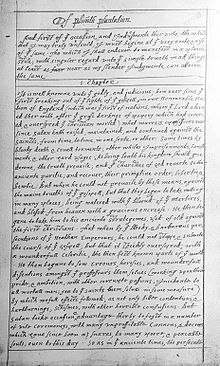

Literary works

William Bradford's most well-known work by far is Of Plymouth Plantation. It was a detailed history in manuscript form about the founding of the Plymouth colony and the lives of the colonists from 1621 to 1646.[47] It is a common misconception that the manuscript was actually Bradford's journal. Rather, it was a retrospective account of his recollections and observations, written in the form of two books. The first book was written in 1630; the second was never finished, but "between 1646 and 1650, he brought the account of the colony's struggles and achievements through the year 1646."[48] As Walter P. Wenska states, "Bradford writes most of his history out of his nostalgia, long after the decline of Pilgrim fervor and commitment had become apparent. Both the early annals which express his confidence in the Pilgrim mission and the later annals, some of which reveal his dismay and disappointment, were written at about the same time."[47] In Of Plymouth Plantation, Bradford drew deep parallels between everyday life and the events of the Bible. As Philip Gould writes, "Bradford hoped to demonstrate the workings of divine providence for the edification of future generations."[48] Despite the fact that the manuscript was not published until 1656, the year before his death, it was well-received by his near contemporaries.

In 1888 Charles F. Richardson referred to Bradford as a "forerunner of literature" and "a story-teller of considerable power"; Moses Coit Tyler called him "the father of American history."[49] Many American authors have cited the manuscript in their works; for example, Cotton Mather referenced it in Magnalia Christi Americana and Thomas Prince referred to it in A Chronological History of New-England in the Form of Annals. Even today it is considered a valuable piece of American literature, included in anthologies and studied in literature and history classes. It has been called "'an American classic' and 'the pre-eminent work of art' in seventeenth-century New England."[49] The Of Plymouth Plantation manuscript disappeared from New England,[when?] "presumably stolen by a British soldier during the British occupation of Boston" and reappeared in Fulham, England.[48] As Philip Gould states, "In 1855, scholars intrigued by references to Bradford in two books on the history of the Episcopal Church in America (both located in England) located the manuscript in the bishop of London's library at Lambeth Palace."[48] A long debate ensued as to the rightful home for the manuscript. Multiple attempts by United States Senator George Frisbie Hoar and others to have it returned proved futile at first. According to Francis B. Dedmond, "after a stay of well over a century at Fulham and years of effort to [e]ffect its release, the manuscript was returned to Massachusetts" on May 26, 1897.[50]

Bradford's journal, even though it did not become Of Plymouth Plantation, was also published. It was contributed to another work entitled Mourt's Relation which was written in part by Edward Winslow, and published in England by one of Bradford's contemporaries. Published in 1622, it was intended to inform Europeans about the conditions surrounding the American colonists at the Plymouth Colony. As governor of the Plymouth Colony, his work was considered a valuable contribution and was thus included in the book. Despite the fact that the book included a large amount of Bradford's work it is not typically referenced as one of his significant works due to the fact that it was published under someone else's name.

In addition to his more well-known work, Bradford also dabbled in poetry. According to Mark L. Sargent, "his poems are often lamentations, sharp indictments of the infidelity and self-interest of the new generation. On occasion, the poems recycle dark images from the history."[51] Although his poetry is still available today to the interested reader it is not nearly as famous as Of Plymouth Plantation.

Bradford's Dialogues are a collection of fictional conversations between the old and new generations. In the Dialogues, conversations ensue between "younge men" and "Ancient men," the former being the young colonists of Plymouth, the latter being "the protagonists from Of Plymouth Plantation" (Sargent 413).[52] As Mark L. Sargent states: "By bringing the young from Plymouth Plantation and the ancients from Of Plymouth Plantation into 'dialogue,'...Bradford wisely dramatizes the act of historical recovery as a negotiation between the two generations, between his young readers and his text."[52] Today, only a small portion of the Dialogues remain; however, a modified copy made by Nathaniel Morton exists.

See also

Notes

- ^ Abrams, 150.

- ^ The fast and thanksgiving days of New England by William DeLoss Love, Houghton, Mifflin and Co., Cambridge, 1895.

- ^ a b c Schmidt, 6.

- ^ a b c Schmidt, 17. Cite error: The named reference "Schmidt17" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Schmidt, 4.

- ^ Philbrick, 13.

- ^ Schmidt, 7.

- ^ Schmidt, 8.

- ^ a b Schmidt, 9.

- ^ Schmidt, 12.

- ^ Goodwin, 12.

- ^ Schmidt, 21.

- ^ Goodwin, 27.

- ^ Schmidt, 33

- ^ Schmidt, 35.

- ^ Philbrick, 17.

- ^ Schmidt, 37

- ^ Goodwin, 38.

- ^ Schmidt, 40.

- ^ Philbrick, 19

- ^ a b Philbrick, 23.

- ^ Philbrick, 25.

- ^ Bradford quoted in Schmidt, 51.

- ^ a b Stratton, 20.

- ^ Philbrick, 40.

- ^ Goodwin, 64.

- ^ a b Schmidt, 80.

- ^ Schmidt, 69.

- ^ Philbrick, 70-73.

- ^ Philbrick, 79.

- ^ Philbrick, 80.

- ^ a b c Philbrick, 76.

- ^ a b Doherty, 73.

- ^ Goodwin, 114.

- ^ Philbrick, 85.

- ^ Haxtun, 17

- ^ a b Philbrick, 114.

- ^ Schmidt, 88.

- ^ Philbrick, 90.

- ^ Philbrick, 99.

- ^ Goodwin, 125.

- ^ Schmidt, 97.

- ^ Goodwin, 159.

- ^ Stratton, 145.

- ^ Stratton, 151, 156, 281, 311

- ^ http://www.mayflowerhistory.com/Passengers/WilliamBradford.php

- ^ a b Wenska, 152

- ^ a b c d Gould, 349

- ^ a b Wenska, 151.

- ^ Dedmond, Francis B (1985). "A Forgotten Attempt to Rescue the Bradford Manuscript". The New England Quarterly. 58.2. Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts and Northeastern University: 242–252. ISSN 0028-4866.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Sargent, 418.

- ^ a b Sargent, 413.

References

- Abrams, Ann Uhry (1999). The Pilgrims and Pocahontas: Rival Myths of American Origin. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 0813334977.

- Doherty, Kieran (1999). William Bradford: Rock of Plymouth. Brookfield, Connecticut: Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 0585213054.

- Goodwin, John A. (1920) [1879]. The Pilgrim Republic: An Historical Review of the Colony of New Plymouth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. OCLC 316126717.

- Gould, Philip (2009). "William Bradford 1590-1657". In Lauter, Paul (ed.). The Heath Anthology of American Literature: Beginnings to 1800. Vol. A. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 348–350. ISBN 0618897992.

- Haxtun, Annie A. (1899). Signers of the Mayflower Compact. Baltimore: The Mail and Express. OCLC 2812063.

- Philbrick, Nathaniel (2006). Mayflower: A Story of Community, Courage and War. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780143111979.

- Sargent, Mark L. (1992). "William Bradford's 'Dialogue' with History". The New England Quarterly. 65.3. Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts and Northeastern University: 389–421. ISSN 0028-4866.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Schmidt, Gary D. (1999). William Bradford: Plymouth's Faithful Pilgrim. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 082851517.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - Stratton, Eugene A. (1986). Plymouth Colony: Its History & People, 1620–1691. Salt Lake City: Ancestry Incorporated. ISBN 0916489132.

- Wenska, Walter P. "Bradford's Two Histories: Pattern and Paradigm in 'Of Plymouth Plantation'". Early American Literature. 13.2 (Fall 1978). Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press: 151–164. ISSN 0012-8163.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

External links

- Bradford's History at the Pilgrim Hall Museum

- William Bradford on MayflowerHistory.com

- Full Text Bradford's book: "Of Plymouth Plantation" (provided by Google Book Search)

- Genealogy of William Bradford