1969 Curaçao uprising

The 1969 Curaçao uprising (known as Trinta di Mei in Papiamento, the local language) was series of riots lasting from May 30 to June 1, 1969. They arose from a labor dispute on the Dutch-controlled Caribbean island nation of Curaçao. Riots destroyed a substantial portion of the island's main city and resulted in the resignation of the prime minister as well as a social prestige for the local language Papiamento.

Background and causes

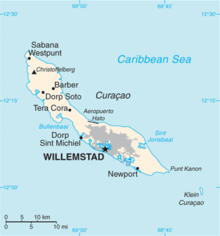

Curaçao is an island in the Caribbean which is a country (Template:Lang-nl) within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. In 1969, it had a population of around 141,000, of whom 65,000 lived in the capital, Willemstad. Until 2010, it was the most populous island and seat of government of the country Netherlands Antilles, the former Dutch colony in the Caribbean comprising six islands.[citation needed]

In the 19th century the island's economy was in poor shape. It had few industries other than dyewood, salt, and straw hats. After the Panama Canal was built and oil was discovered in Venezuela's Maracaibo Basin, Curaçao's economic situation changed for the better. Shell opened a refinery in 1918; it was continually expanded until 1930. The plant's production peaked in 1952, when it employed around 11,000 people. This economic boom attracted a number of immigrants, particularly from other Caribbean islands, Suriname, Madeira, and the Netherlands. Thereafter, the number of people working in the oil industry had shrunk. By 1969, Shell only employed around 4,000 people. This was a result both of automation and of sub-contracting: employees of sub-contractors typically received lower wages than Shell workers. Unemployment rose from 5,000 in 1961 to 8,000 to 1966. Nonwhite, unskilled workers were particularly affected. The government focused on attracting tourism. Though this brought some economic growth, it did little to reduce unemployment.[1]

The rise of the oil industry had led to a number of civil servants being brought in, mostly from the Netherlands. This led to a segmentation of Curaçaoan society into landskinderen, those who had been in Curaçao for generations, and makamba, the new inhabitants from Europe. The latter had closer ties to the Netherlands and spoke Dutch, while the former spoke Papiamento and had a more pronounced Antillean identity.[2]

Another issue that would come to the fore in the uprising was the Netherlands Antilles', and specifically Curaçao's, relationship with the Netherlands. Its status had been changed in 1954 by the Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Under the charter, the Netherlands Antilles, like Suriname until 1975, was a part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, but not of the Netherlands itself. Foreign policy and national defense are Kingdom matters and presided over by the Council of Ministers of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, which consisted of the full Council of Ministers of the Netherlands with one minister plenipotentiary for each of the countries Netherlands Antilles and Suriname. Other issues, however, were governed at a more local level, that of the country (Netherlands Antilles) or island (the island of Curaçao). Although this system had its proponents, who pointed to the fact that managing its own foreign relations and national defense would be too costly for a small country like Curaçao, many Netherlands Antilleans saw it as a continuation of the area's subaltern colonial status. Similarly, Dutch cultural dominance in Curaçao was another source of conflict. Specifically, the island's official language was Dutch, meaning that this was the language used in schools. Many Curaçaoans' native language, however, was Papiamento. This created difficulties for many students.[3]

A high Antillean government official claimed that the island's wide-reaching mass media was one of the uprising's causes. People in Curaçao were well aware of events in the United States, Europe, and Latin America. In addition to their access to media, many Antilleans traveled abroad, including many who studied abroad. Moreover, many tourists from the U.S. and the Netherlands visit Curaçao and many workers from abroad work in Curaçao's oil industry. Therefore, Curaçao's inhabitants were very much aware of global events. The uprising would parallel anti-colonial, anti-capitalist, and anti-racist movements throughout the world. It was particularly influenced by the Cuban Revolution. Government officials in Curaçao would falsely claim that Cuban communists were directly involved in sparking the uprising. However, the revolution did have an indirect influence in that it inspired many of the participants. Many of the uprising's leaders donned khaki uniforms similar to those worn by Fidel Castro. Similarly, black power movements were emerging throughout the Caribbean and in the United States at the time. Though foreign black power figures were again not directly involved in the 1969 uprising, they did inspire many of its participants. As in the U.S. and Caribbean countries such as Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, or Barbados, blacks in Curaçao were hit disproportionately by poverty and faced racism and discrimination. The movement leading up to the 1969 uprising therefore used many of the same symbols and rhetoric as black power and civil rights movements in those countries.[4]

Another issue that contributed to the uprising lay in local politics. The Democratic Party (DP) had been in power in the Netherlands Antilles since 1954. A center-left party, the DP was more closely connected to the labor movement than its major rival, the National People's Party (NVP). It made promises of improving workers' conditions that it was unable to make good on. Meanwhile, the DP was also mainly associated with the white segments of the working class and blacks criticized it for primarily advancing white interests.[5] The 1960s also saw the rise of radicalism in Curaçao. Many students went to the Netherlands for studies and some returned with radical left-wing ideas. They founded the Union Reformista Antillano (URA) in 1965. It established itself as a socialist alternative to the established parties, though it was more reformist than revolutionary in outlook. Beyond parliamentary politics, the Vitó movement emerged. Vitó was a magazine at the center of a movement aiming to put an end to the economic and political exploitation of the masses thought to be a result of neo-colonialism. When Vitó started being published in Papiamento rather than Dutch in 1967, it gained a mass following. It had close ties with radical elements in the labor movement. Papa Godett, a leader in the dock workers' union, worked together with Stanley Brown, the editor of Vitó.[6]

Labor dispute

Curaçao was thought an unlikely site for political turmoil, despite low wages, high unemployment, and economic disparities between blacks and whites. This tranquility was attributed by the island's government to the strength of family ties. In a 1965 pitch to investors, the government ascribed the absence of a communist party and labor unions' restraint to the fact that "Antillean families are bound together by unusually strong ties and therefore extremist elements have little chance to interfere in labor relations."[7] Labor relations, including those between Shell and the refinery's workers, had indeed generally been fairly peaceful. After two minor strikes in the 1920s, a contract committee for Shell workers was established after a strike in 1936. Only from 1942 on did workers, though only those with Dutch nationality, have the right to elect their representatives on this committee. In 1955, the American CIO's Puerto Rican section aided the workers in launching the Petroleum Workers' Federation of Curaçao (PWFC). In 1957, the Federation reached a collective bargaining agreement.[8]

The PWFC was part of the General Conference of Trade Unions (AVVC), the island's largest labor confederation. The AVVC generally took a moderate stance in labor negotiations and was often criticized for this, and for its close relationship to the Democratic Party, by the more radical parts of the Antillean labor movement. The Curaçao Federation of Workers (CFW), another union in the AVVC, represented construction workers employed by the Werkspoor Caribbean Company, a Shell sub-contractor. It was to play an important role in the events that led to the uprising. Among the unions criticizing the AVVC was the General Dock Workers Union (AHU), led by Papa Godett and Amador Nita. It was guided by a revolutionary ideology seeking to overthrow the remnants of Dutch colonialism, especially discrimination against blacks. Godett was closely allied with Stanley Brown, the editor of Vitó. The labor movement in the time before the 1969 uprising was very fragmented and personal animosity between labor leaders further exacerbated this situation.[9]

In May 1969, there was a labor dispute between the CFW and Werkspoor. It revolved around two central issues. For one, Antillean Werkspoor employees received lower wages than workers from the Netherlands or other Caribbean islands as compensation for the latter working away from home. Secondly, Werkspoor employees performed the same work as Shell employees but received lower wages. Werkspoor's response pointed to the fact that it could not afford to pay higher wages under its contract with Shell. Vitó was heavily involved in the strike, helping to keep the conflict in the public consciousness. Though the dispute between CFW and Werkspoor received the most attention, that month there was quite a bit of labor unrest taking place in the Netherlands Antilles.[10]

On May 6, around 400 Werkspoor employees went on strike. The Antillean Werkspoor workers received support and solidarity both from non-Antilleans at Werkspoor and from other Curaçaoan unions. On May 8, this strike ended with an agreement to negotiate a new contract with government mediation. These negotiations failed, leading to a second strike starting on May 27. The workers received significant support. Shell employees and other contractors' employees working for Shell struck in solidarity with Werkspoor employees on May 29. That same day, thirty to forty workers marched to Fort Amsterdam, the Antillean government's seat, contending that the government itself was contributing to wages being kept low. While the strike was led by the CFW, the PWFC, under pressure from its rank and file, showed solidarity with the strike. It decided to call for a strike to support the Werkspoor workers.[11]

Uprising

On the morning of May 30, more unions announced strikes in support of the CFW's struggle against Werkspoor. Some three to four thousand workers gathered at a strike post. While the CFW emphasized that this was merely an economic dispute, Papa Godett, the dock workers' leader and Vitó activist, advocated a political struggle in his speech to the strikers. He called for another march to Fort Amsterdam, which was seven miles away in downtown Willemstad. By the time this march started moving towards the city center, some 5,000 workers, most of them black,[12] were part of it and as it progressed through the city more joined it. There were no protest marshals and leaders had little control over the crowd's actions.[13]

The march started becoming increasingly violent. First, a pick-up truck with a white driver was set on fire and two stores were looted. Then, large commercial buildings including a Coca-Cola bottling plant and a Texas Instruments factory were attacked and marchers entered the buildings to halt production. Texas Instruments had a poor reputation because it had prevented unionization among its employees. Housing and public buildings, on the other hand, were generally spared. Once it became aware of it, the police moved to stop the rioting and also called for assistance from both the local volunteer militia and Dutch troops stationed in Curaçao. The police, with the mere sixty officers at the scene being unable to halt the march, wound up enveloped by the demonstration, with cars within it attempting to hit them. Then, Papa Godett was shot in the back by the police. He would claim that the police had orders to kill him personally, while law enforcement claimed that officers had only done what was necessary to save their own lives.[14]

The police moved to secure a hill on the march route. There they were attacked with a fire truck that had been sent to support them and whose driver had been shot and killed from within the crowd. They were also pelted with rocks. Meanwhile, Godett was taken to the hospital by members of the demonstration to receive treatment for his wound. Parts of the march followed him there. The main part of the march moved on to Willemstad's central business district. There the crowd broke up into smaller groups that looted a number of stores and a small theater. One shop that had been criticized by Vitó for having particularly poor working conditions was set on fire and the flames spread to other buildings.[15]

Police, local volunteers, firemen, and Dutch marines fought hard to stop the rioting, put out fires set in looted buildings, and guard banks and other key buildings while thick plumes of dark smoke emanated from the city center.[16] However, many of the buildings in this part of Willemstad were old and burned easily. The compact nature of the central business district also hampered firefighting efforts. In the afternoon, clergymen put out a statement over the radio urging the looters to stop. Meanwhile, union leaders announced that they had reached a compromise with Werkspoor. Under this deal Shell workers would receive equal wages whether they were employed by contractors or not and independently of their national origin.[17]

However, despite the struggle's economic aims having been achieved, rioting continued throughout the night. It slowly abated on May 31. The uprising's focus shifted from economic demands to political goals. Union leaders, both radical and moderate, demanded that the government resign, threatening a general strike. Workers broke into a radio station, forcing it to broadcast this demand.[18] They argued that failed economic and social policy had led to the grievances that led to the uprising. On May 31, Curaçaoan labor leaders met with union representatives from Aruba, also part of the Netherlands Antilles. The Aruban delegates agreed with the demand for the government's resignation, announcing that Aruban workers, too, would go on a general strike should it be ignored. By the night of May 31 to June 1, however, the violence had ceased. Another 300 Dutch marines arrived on the island on June 1 to maintain order.[19]

All in all, the uprising cost two lives, identified as A. Gutierrez and A. Doran, and injuries to 22 police officers and 57 others and led to a total of 322 arrests. 43 businesses and 10 other buildings were burned out in the course of the riots and 190 buildings were damaged or looted. Thirty vehicles were destroyed by fire. The total damage caused by the uprising was around 40 million US dollars. The looting was, however, highly selective: businesses owned by whites were primarily targeted, while tourists were not.[20] The uprising achieved both its economic demands, wage equality for Shell workers, and its political demands, since on June 3 the Estates of the Netherlands Antilles, pressured by the Chamber of Commerce, which feared further strikes and violence, announced new elections for September of that year. Prime Minister Ciro Domenico Kroon, who went into hiding during the uprising,[21] subsequently also resigned and was replaced by an interim administration.[22]

Aftermath

Among the lasting effects of Trinta di Mei was the increased use and prestige of Papiamento. According to Frank Martinus Arion, a Curaçaoan writer, "Trinta di Mei allowed us to recognize the subversive treasure we had in our language". It empowered Papiamento speakers and sparked discussions about the use of the language. Vitó, the magazine that had played a large part in the build-up to the uprising, had long called for Papiamento to become Curaçao's official language once it became independent of the Netherlands. Indeed, it was recognized as an official language on the island, along with English and Dutch, in 2007. Curaçaoan parliamentary debate is now conducted in Papiamento and most radio broadcasts are in this Creole language. However, most schools still teach in Dutch.[23]

Notes

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 33–35, 55–57.

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 35–36.

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 42–43, 48–49.

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 7–13.

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 50–52.

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 62–65.

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 4.

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 36–37.

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 59–62.

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 69–70.

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 71–73.

- ^ "Striking Oil Workers Burn, Loot in Curacao". Los Angeles Times. May 31, 1969. p. 2.

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 74–77.

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 78–79.

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 79–81.

- ^ "Striking Oil Workers Burn, Loot in Curacao". Los Angeles Times. May 31, 1969. p. 2.

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 81–82, 85.

- ^ "Strikers on Curacao Insist Regime Quit; Two Dead in Rioting". New York Times. May 31, 1969. p. 1.

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 83–86.

- ^ "Strikers on Curacao Loot Resort; Dutch Troops Used". New York Times. May 31, 1969. p. 1., "Strikers on Curacao Insist Regime Quit; Two Dead in Rioting". New York Times. May 31, 1969. p. 1.

- ^ Maidenberg, June 2, 1969.

- ^ Anderson/Dynes 1975, pg. 83, 86–87.

- ^ Eckkramer 2007, Romero 2010.

Bibliography

- "Dutch Report on Marines". New York Times. May 31, 1969. p. 2.

- "U.S. on Standby Alert". New York Times. May 31, 1969.

- "Injuries Estimated at 100". New York Times. June 1, 1969.

- "Dutch Send Reinforcements". New York Times. June 1, 1969.

- "Workers Threaten to Renew Rioting in Curacao". The Washington Post. Reuters. June 1, 1969. p. 27.

- "Sullen Calm Returns to Curacao After Rioting". Los Angeles Times. June 1, 1969. p. 14. ISSN 0458-3035.

- "Dutch Send Riot Forces To Curacao". The Washington Post. June 2, 1969. p. A10.

- "Strikers on Curacao Insist Regime Quit". New York Times. June 2, 1969. p. 1.

- "U.S. Declines Comment". New York Times. June 2, 1969.

- "Troops Put Tight Lid On Curacao". The Washington Post. June 3, 1969. p. A16.

- "Curacao Plans New Vote". The Washington Post. June 4, 1969. p. 14.

- "'Workers' Island' Or Tourist Eden? Curacao Votes To Decide". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. September 3, 1969. p. 3.

- Allen, Rose Mary (October 2010). "The Complexity of National Identity Construction in Curaçao, Dutch Caribbean". European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies (89). ISSN 0924-0608.

- Anderson, W. A.; R. R. Dynes (1973). "Organizational and Political Transformation of a Social Movement: A Study of the 30th of May Movement in Curacao". Social Forces. 51 (3): 330–341. doi:10.1093/sf/51.3.330. ISSN 0037-7732.

- Anderson, William Averette; Dynes, Russell Rowe (1975). Social movements, violence, and change: the May Movement in Curaçao. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 9780814202401.

- Arnold, Albert James; Rodríguez-Luis, Julio; Dash, J. Michael (1994). A History of Literature in the Caribbean: English- and Dutch-speaking countries. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 9789027234483.

- Eckkrammer, Eva (2007). "Papiamentu, Cultural Resistance, and Socio-Cultural Challenges: The ABC Islands in a Nutshell". Journal of Caribbean Literatures. 5 (1): 73–93. ISSN 2167-9460.

- Kent, Francis B. (May 2, 1973). "Dutch Plan to Give Up Caribbean Islands, Bringing End to Empire". Los Angeles Times. pp. A12-13. ISSN 0458-3035.

- Maidenberg, H. J. (June 2, 1969). "Premier Silent as Rioters in Curacao Insist He Quit". New York Times. p. 1.

- Maidenberg, H. J. (June 3, 1969). "Dutch Patrolling Curacao Streets". New York Times. p. 9.

- Maidenberg, H. J. (June 3, 1969). "Government to Quit In Curacao's Strife". New York Times. p. 1.

- Oostindie, Gert; Klinkers, Inge (2003). Decolonising the Caribbean: Dutch Policies in a Comparative Perspective. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789053566541.

- Rabinovich, Avraham (October 1970). "Caribbean Jewish communities suffer from Black power riots". The Chronicle Review. p. 188.

- Romero, Simon (5 July 2010). "A Language Thrives in Its Caribbean Home". The New York Times. p. 7. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Sharpe, Michael Orlando (2005). "Globalization and Migration: Post-Colonial Dutch Antillean and Aruban Immigrant Political Incorporation in the Netherlands". Dialectical Anthropology. 29 (3–4): 291–314. doi:10.1007/s10624-005-3477-3. ISSN 0304-4092.

- Sharpe, Michael Orlando (2009-04-21). "Curaçao, 1969 Uprising". In Ness, Immanuel (ed.). The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 1500 to the Present. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 942–943. ISBN 9781405184649.

- Weyland, John (July 7, 1971). "Netherlands Antilles Now Stable After Two Years of Disturbances". Lewiston Daily Sun. p. 14.