Whiplash (decorative art)

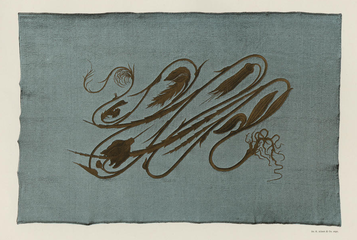

The whiplash or whiplash line is a motif of decorative art and design that was particularly popular in Art Nouveau. It is an asymmetrical, sinuous line, often in an ornamental S curve, usually inspired by natural forms such as plants and flowers, which suggests dynamism and movement.[1] It took its name from a woven fabric panel called "Coup de Fouet" ("Whiplash") by the German artist Hermann Obrist (1895) which depicted the stems and roots of the cyclamen flower. The panel was later reproduced by the textile workshop of the Darmstadt Artists Colony.

Curling whiplash lines were modelled after natural and vegetal forms, particularly the cyclamen, iris, orchid, thistle, mistletoe, holly, water lily and from the stylized lines of the swan, peacock, dragonfly and butterfly.[2]

In architecture, furniture and other decorative arts, the decoration was entirely integrated with the structure. The whiplash lines were frequently interlaced and combined with twists and scrolls to inspire a poetic and romantic association. Femininity and romanticism was represented by the lines of long curling hair intertwined with flowers.[2]

Designers such as Henry van de Velde used the whiplash line to create a sense of tension and dynamism. He wrote: "A line is a force like other elementary forces. Several lines put together but opposed act like the presence of multiple forces.[3]

Noted designers who used the whiplash line included Aubrey Beardsley, Hector Guimard, Alphonse Mucha and Victor Horta. In the Art Nouveau period, the whiplash line appeared frequently in furniture design, railings and other ornamental iron work, floor tiles, posters and jewelry. It became so common that critics of Art Nouveau ridiculed it as "the noodle style".[4]

Origins

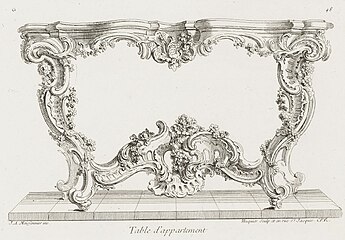

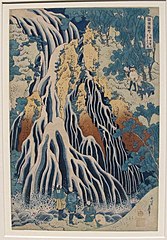

The twisting and curving lines of the whiplash form have a long history. They are similar to the Arabesque design, used particularly in Islamic art, such as the ceramic tiles of the mosque of Samarkand in Central Asia, They featured prominently in the lavish decoration of the rocaille or rococo style in the early 18th century. They were found in the Japanese prints of Katsushika Hokusai, which became popular in France just as the Art Nouveau movement was beginning, and which particularly inspired the paintings of flowers by Vincent van Gogh, such as The Irises (1890).[5]

-

Arabesque pattern on a tile from Samarkand (15th century)

-

Waterfall of Kirifuri by Katsushika Hokusai (1830–1834)

-

Irises by Vincent van Gogh (1890)

-

"Seaweed" wallpaper design by William Morris and J. H. Dearle (1890)

-

Decoration for a title page by Aubrey Beardsley (1890)

-

Woven whiplash design depicting the stems of cyclamen flowers, by Hermann Obrist (1895)

-

Whiplash motif at a metalwork railing. Editorial Montaner i Simón, Barcelona, Spain. (1881)

-

Casa vicens, by Antoni Gaudí i Cornet. Railing detail with whiplash motif (1883). Barcelona, Spain. Early Art nouveau building

Architecture

The Belgian architect Victor Horta was among the first to introduce the whiplash curve into Art Nouveau architecture, particularly in the wrought iron stairways and complementary ceramic floors and painted walls of the Hôtel Tassel in Brussels (1892–93). The lines were was inspired by the curving stems of plants and flowers. The French architect Hector Guimard also adapted the curving lines, particularly in the gateway, stairway and interior decoration of the Castel Béranger in Paris (1894–98), and in the edicules over the entrances of the Paris Métro that he designed for the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900. Guimard also used the curving whiplash line on a large scale on the facade of the house he built for he ceramics manufacturer Coilliot in Lille (1898–1900).[6]

Another major figure using the whiplash form was the furniture designer Louis Majorelle, who incorporated the twisting whiplash line not only into his furniture, but also into cast iron staircase railings, stained glass windows.

The whiplash line in ceramics was also sometimes used for exterior decoration, for example under the peristyle in the courtyard of the Petit Palais in Paris, built for the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition. It also appears in the curving cast iron staircase and ceramic floors of the interior of the Petit Palais. The architect Jules Lavirotte covered the facade of several of houses in Paris, particularly the Lavirotte Building on Avenue Rapp, with curling ceramic whiplash designs made by the ceramics firm of Alexandre Bigot.

-

Floor of the Hôtel Tassel, with the characteristic Whiplash design. (1892–93)

-

Entrance of Castel Béranger by Hector Guimard (1894–98)

-

Facade of the Maison Coilliot in Lille by Hector Guimard (1898–1900)

-

Whiplash line on floor of the gallery of the Petit Palais (1900)

-

Entrance of 20 Avenue Rapp by Jules Lavirotte

-

Atelier Elivira facade by in Jugendstil by August Endell. Munich (1896–97)

Wrought iron and cast iron

The use of wrought iron or cast iron in scrolling whiplash forms on doorways, balconies and gratings became one of the prominent features of the Art Nouveau style. The architect Victor Horta, who had worked on the construction of iron and glass Royal Greenhouses of Laeken in Belgium, was one of the first to create Art Nouveau ironwork, followed quickly by Hector Guimard, whose iron edibles for the entrances of the Paris Métro became an emblem of the style.

-

Gate of La Hublotière, country house of Hector Guimard (1896)

-

Main stairway of the Castel Béranger by Hector Guimard (1895–98)

-

Art Nouveau stairway of the Petit Palais 0f the 1900 Paris Exposition

-

Paris Métro Station entrance at Station Boissière by Hector Guimard (1900)

-

Cast iron Paris Métro medallion by Hector Guimard (1900)

-

Maison Saint-Cyr in Brussels by Gustave Strauven (1901–1903)

-

Entrance grill of Villa Majorelle in Nancy (1901–02)

-

Entrance gate of Guell pavilion by Antoni Gaudí (1883–87)

Graphic arts and painting

The whiplash line was especially popular in posters and the graphic arts. In the posters of Alphonse Mucha and Koloman Moser, it was frequently used to depict women's hair, which became a central motif of the posters. After 1900 the whiplash lines tended to be more styled and abstract.

The line also appeared in decorative paintings, such as the series of wall paintings made by Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh of the Glasgow School. Her paintings, particularly the White Rose and Red Rose decorative panels (1903), were exhibited at gallery Vienna Secession, where they may have influenced the decorative paintings of Gustav Klimt at the Stoclet Palace made the following year.

-

Salome by Aubrey Beardsley (1893)

-

Design by Otto Eckmann based upon stems of wheat (1895)

-

Poster of Sarah Bernhardt by Alphonse Mucha (1896). The actress's hair is a profusion of whiplash lines.

-

Poster for tea by Henri Meunier, with the steam rising in a whiplash form (1897)

-

The Kiss by Peter Behrens (1898)

-

illustration from Ver Sacrum by Koloman Moser (1900)

-

White Rose and Red Rose decorative panel, by Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh (1903)

-

Prep. design of The Embrace by Gustav Klimt (1904)

Furniture and ornament

Art Nouveau was a comprehensive form of decoration, in which all the elements; furniture, lamps, ironwork, carpets, murals, and glassware, had to be in the same style, or the harmony was broken. Victor Horta, Hector Guimard, Henry van de Velde and other Art Nouveau architects designed chairs, tables, lamps, carpets, tapestries ceramics and other furnishings with similar curling whiplash lines. The whiplash line was intended to show the clear break from the eclectic historical styles that had dominated furniture and decoration for most of the 19th century. Henry Van de Velde and Horta in particular integrated the whiplash lines into their furniture, both in the shapes of desks and tables, the legs, in the brassware handles, and in railings and lamps, as well as in the chairs. Right angles were nearly banished from the works. [7]

An important furniture workshop was created in the French city of Nancy by Louis Majorelle. Many designs with the whiplash line inspired by water lilies and other natural forms were created by Majorelle's designers. In Belgium the most notable designer using the motif was Gustave Serrurier-Bovy After 1900, the whiplash lines became simpler and more stylized. In the Glasgow School in Scotland, the motif was used in furniture by Charles Rennie Mackintosh and in highly-stylized glass and paintings by his wife, Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh. [8]

-

Interior design for Hôtel Solvay by Victor Horta (1898-1900)

-

Sketch of an ornament by Victor Horta (Horta Museum, Brussels)

-

Buffet by Hector Guimard (1899–1900) (Bröhan-Museum, Berlin)

-

Desk, chair and lamps by Henry van de Velde (1898–99)

-

Ceiling light by Henry van de Velde (1898)

-

Bed and mirror by Gustave Serrurier-Bovy (1898–99), (Musée d'Orsay)

-

Water Lily chair by Louis Majorelle (1900)

-

Bed by Louis Majorelle, with lines inspired by the water lily. (Musée d'Orsay)

-

Wall cabinet by Louis Majorelle (Late 19th century) (Walters Art Museum)

-

Detail of Vitrine by Louis Majorelle (c. 1910)

-

Table by Émile Gallé, c. 1900 (Bröhan Museum, Berlin)

-

Credenza by Eugène Gaillard (c. 1900) (Art Institute of Chicago)

-

Piano design by Charles Rennie Mackintosh in his House for an Art Lover.

Ceramics and glass

In ceramics and glass, the whiplash lines were mostly taken from floral and animal forms. After 1900 they kept the floral motifs but became simpler and more stylized.

-

Cup Par une telle nuit by Émile Gallé, France, (1894)

-

Vase design by Georges de Feure (1901) (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

Glass vase by Louis Comfort Tiffany (c. 1893-96)

-

Design for a Limoges ceramic vase by Georges de Feure (1903)

-

Glass vase by Daum studio, Nancy, (c. 1910)

-

Window for the House of an Art Lover, by Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh (1901)

-

The ceramic Paris facades of architect Jules Lavirotte made lavish use of the whiplash lines.

-

Porcelain and bronze vase by Otto Eckmann (1897–99)

Jewelry

European jewelers were very quick to adapt the whiplash line to pendants and other ornaments. The Belgian designer Philippe Wolfers was one of the pioneers of the style. His drawings show how he carefully analysed the forms of flowers and plants and used them in his jewelry. His work often crossed the frontiers between sculpture and decorative art, inspired by the lines of forms ranging from dragonflies to bats to Grecian masks. He made not only jewelry, but also bronzes, lamps, vases, glassware and other decorative objects, produced mostly for the Belgian firm Val Saint Lambert. [9]

In Paris, the most prominent jewelry designers were René Lalique and Fouquet. Their designers made abundant use of the whiplash line to suggest natural forms, from waterfalls to iris flowers. Other artists, including Alfons Mucha, contributed jewelry designs incorporating the whiplash line.

-

Design drawing of flower stems by Philippe Wolfers (1896)

-

Dragonfly pendant by Philippe Wolfers, made of gold, opal, enamel, rubies and diamonds. (1903-1904)

-

Japanese lily ornament by Philippe Wolfers (1898)

-

Peacock feather belt buckle by Philippe Wolfers (1898)

-

Iris corsage ornament by Louis Comfort Tiffany (c. 1900)

-

Jewelry designs for Fouquet jewellers by Alfons Mucha (1901)

-

Comb of horn, gold, and diamonds by René Lalique (c. 1902) (Musée d'Orsay)

Notes and citations

- ^ "The whiplash line". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ a b Renault & Lazé 2006, p. 107-108.

- ^ Fahr-Becker 2015, p. 152.

- ^ "The whiplash line". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ Fahr-Becker 2015, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Ducher 1988, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Fahr-Becker 2015, pp. 152–159.

- ^ De Morant 1970, pp. 445–447.

- ^ Fahr-Becker 2015, pp. l151-152.

Bibliography

- Fahr-Becker, Gabriele (2015). L'Art Nouveau (in French). H.F. Ullmann. ISBN 978-3-8480-0857-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ducher, Robert (2014). La charactéristique des styles (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-0813-4383-2.

- Renault, Christophe; Lazé, Christophe (2006). Les styles d'architecture et du mobilier (in French). Editions Jean-Paul Gisserot. ISBN 978-2-8774-7465-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - De Morant, Henry (1970). Histoire des arts décoratifs (in French). Librarie Hachette.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)