Archiacanthocephala

| Archiacanthocephala | |

|---|---|

| |

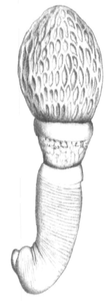

| Apororhynchus hemignathi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Acanthocephala |

| Class: | Archiacanthocephala Meyer, 1931[1] |

Archiacanthocephala is a class within the phylum of Acanthocephala.[2] They are parasitic worms that attach themselves to the intestinal wall of terrestrial vertebrates, including humans. They are characterised by the body wall and the lemnisci (which are a bundle of sensory nerve fibers), which have nuclei that divide without spindle formation or the appearance of chromosomes or it has a few amoebae-like giant nuclei. Typically, there are eight separate cement glands in the male which is one of the few ways to distinguish the dorsal and ventral sides of these organisms.

Taxonomy

Genetic data are not available for the genus Apororhynchus in public databases and Apororhynchus has not been included in phylogenetic analyses thus far due to insufficiency of morphological data. However, the lack of features such as an absence of a muscle plate, a midventral longitudinal muscle, lateral receptacle flexors, and an apical sensory organ when compared to the other three orders of class Archiacanthocephala indicate it is an early offshoot (basal).[3] There are four orders in the class Archiacanthocephala:

| Archiacanthocephala |

| Phylogenetic reconstruction for select species in the class Archiacanthocephala[4] |

Description

All species in the class Archiacanthocephala are terrestrial and use terrestrial insects and myriapods as intermediate hosts and predatory birds and mammals as a primary host.[5] They attach themselves to the intestinal wall using a hook covered proboscis. The location of the eight cement glands in the male is one of the few ways to distinguish the dorsal and ventral sides of these organisms. The worms are also characterised by the body wall and the lemnisci (which are a bundle of sensory nerve fibers), which have nuclei that divide without spindle formation or the appearance of chromosomes or it has a few amoebae-like giant nuclei.

See also

References

- ^ Meyer, A.: Neue Acanthocephalen aus dem Berliner Museum. Begründung eines neuen Acanthocephalensystems auf Grund einer Untersuchung der Berliner Sammlung. Zoologische Jahrbücher, Abteilung für Systematick, Ökologie und Geographie der Tiere 62, 1931, p. 65-68.

- ^ Crompton, David William Thomasson; Nickol, Brent B.: Biology of the Acanthocephala, Cambridge University Press, 1985, p. 31. [1]

- ^ Herlyn, H. (2017). "Organization and evolution of the proboscis musculature in avian parasites of the genus Apororhynchus (Acanthocephala: Apororhynchida)". Parasitology Research. 116 (7): 1801–1810. doi:10.1007/s00436-017-5440-z. PMID 28488043.

- ^ Nascimento Gomes, Ana Paula; Cesário, Clarice Silva; Olifiers, Natalie; de Cassia Bianchi, Rita; Maldonado, Arnaldo; Vilela, Roberto do Val (December 2019). "New morphological and genetic data of Gigantorhynchus echinodiscus (Diesing, 1851) (Acanthocephala: Archiacanthocephala) in the giant anteater Myrmecophaga tridactyla Linnaeus, 1758 (Pilosa: Myrmecophagidae)". International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife. 10: 281–288. doi:10.1016/j.ijppaw.2019.09.008. PMC 6906829. PMID 31867208.

- ^ Ribas A, Casanova JC (2006) Acanthocephalans. In: Morand S, Krasnov BR, Poulin R (eds) Micromammals and macroparasites. From Evolutionary Ecology to Management. Springer–Verlag, Tokyo, pp 81–90