Nathan Meeker

Nathan C. Meeker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 12, 1817 Euclid, Ohio, US |

| Died | September 29, 1879 (aged 62) Meeker, Colorado, US |

| Signature | |

Nathan Cook Meeker (July 12, 1817 – September 30, 1879) was a 19th-century American journalist, homesteader, entrepreneur, and Indian agent for the federal government. He is noted for his founding in 1870 of the Union Colony, a cooperative agricultural colony in present-day Greeley, Colorado.

In 1878, he was appointed U.S. Agent at the White River Indian Agency in western Colorado. The next year, he was killed by Ute warriors in what became known as the Meeker Massacre, during the White River War. His wife and adult daughter were taken captive for about three weeks. In 1880, the United States Congress passed punitive legislation to remove the Ute from Colorado to Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation in present-day Utah, and take away some land formerly guaranteed them.

The town of Meeker, Colorado and Mount Meeker in Rocky Mountain National Park are named for him.

Early life

Nathan Cook Meeker was born in Euclid, Ohio on July 12, 1817,[1][a] to Enoch and Lurana Meeker.[1] He had three brothers. Meeker was a writer and submitted articles to area publications when he was a boy.[1] He left home at 17 years-of-age for New Orleans, where he worked as a copy boy for the New Orleans Picayune. In the late 1830s, Meeker returned to Ohio, where he attended and graduated from Oberlin College.[1]

Early career and family

After college, Meeker worked as a school teacher in Cleveland and Philadelphia. He saved up his money to move to New York, hoping to fulfill a desire to become a poet. In New York, he became a contributor to the Mirror, which was owned by N.P. Willis. Unable to support himself, he moved back to Euclid and was a traveling salesman.[1] Meeker was also a farmer.[2]

Meeker married Arvilla Delight Smith, a Congregationalist, on April 8, 1844.[3] He was baptized a Disciple of Christ to address her concern about his lack of faith. Smith was concerned that Meeker was younger than her. So, he stated that his year of birth was 1814 on their marriage certificate. The couple settled in the Trumbull Phalanx colony in Ohio. The colony was based upon the utopian theories of Charles Fourier. Arvilla taught kindergarten and Nathan was a teacher, historian, auditor, librarian, secretary, and poet laureate. In 1845, their son Ralph Lovejoy was born. Two years later George Columbus was born at the colony.[1] The Trumbull Phalanx colony failed due to financial and health issues in the fall of 1847.[1]

In 1847, Meeker opened a store with his brothers in Cleveland. Rozene was born in 1849 in Munson. The store failed in 1850.[1] Meeker opened another store in Hiram in 1852. He was asked to help found the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute by the Disciples of Christ, but he was furious when his claim was held up because he sold whiskey. He only sold whiskey by prescription, but was so angry over the misunderstanding that he left the church.[1] In 1854, Mary was born in Hiram, and three years later Josephine was born there. Meeker lost his store and property during the Great Panic of 1857. He moved to Dongola, Illinois, where he opened a small store and grew fruit.[1]

Meeker wrote articles, often about sociology, that were published by the Cleveland Plaindealer and reprinted by Horace Greeley in the New-York Tribune.[1] His first novel, The Adventures of Captain Armstrong was published in 1856, with Horace Greeley's assistance.[1]

Meeker became a war correspondent for Greeley in his Cairo, Illinois office during the Civil War. He was present at and reported on the battle at Fort Donelson,[1] among other journalists such as Junius Henri Browne and Charles Carleton Coffin.[4] Meeker became made an agricultural journalist and editor at the end of the war for the New-York Tribune.[2][1] Meeker's novel Life in the West or Stories of the Mississippi Valley was published in 1866. He went to the Rocky Mountains for the Tribune in 1869, and was inspired to live there.

Union Colony

Meeker, who was interested in communal and cooperative farms, created his vision of a utopian community based upon Christianity and communal economic enterprise, which was a modification of Charles Fourier’s definition of a utopian society.[2] With the backing of his editor Horace Greeley, Meeker organized the Union Colony (later the town of Greeley) to be settled in the Colorado Territory. He advertised for applicants to move to the South Platte River basin, in what was intended as a cooperative venture for people of "high moral standards." Meeker received approximately 3,000 replies that winter, and accepted about 700 of them to purchase shares.[2][5] With the capital from the shares, in 1870 Meeker purchased 2,000 acres (8 km²), primarily from Native Americans, at the confluence of the South Platte and the Cache La Poudre River (Powder Bag) rivers near present-day Greeley. The venture relied on funding from Horace Greeley.[2][5] Meeker also founded the Greeley Tribune in 1870.[2]

The settlers brought irrigation techniques to northeastern Colorado, and helped attract additional agricultural settlement in the region.[citation needed] The community failed on a couple of counts. It was not financially successful and the community members had not adopted the Christian values that Meeker espoused.[2]

Indian agent

In 1878, eight years after the founding of the colony, Meeker was appointed United States (US) Indian agent at the White River Ute Indian Reservation by Henry M. Teller, the Governor of Colorado, on the western side of the continental divide. He received this appointment, although he lacked experience with Native Americans. While living among the Ute, Meeker tried to extend his policy of religious and farming reforms, but they were used to a hunter-gatherer lifestyle with seasonal bison hunting, as opposed to one which would require them to settle on a particular piece of land.[2]

The federal government had been trying to persuade the Ute to abandon their nomadic lifestyle, and become farmers. It wanted them to send their children to European-American style schools and assimilate into majority culture.

Meeker Massacre

Meeker wanted to convert the Ute from what he considered their state of primitive savagery to become subsistence farmers who adopted his techniques. He was warned that the Ute resented his reforms and attempts at conversion. Ignoring these reports, Meeker ordered that a horse racing track be plowed under to convert the track and horses' pasturage to farmland. The Ute held their horses as a chief source of status and wealth, and considered the order an affront. Meeker suggested to one man that the tribe had too many horses and they would have to kill some to give more land over to agriculture.[citation needed]

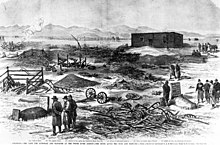

After having the track plowed, Meeker had a tense conversation with an irate Ute chief. Meeker wired for military assistance, claiming that he had been assaulted by an Indian, driven from his home, and severely injured. The government sent approximately 150-200 soldiers, led by Major Thomas T. Thornburgh, commander of Fort Steele in Wyoming, to settle the affair.[citation needed] On September 29, 1879, before troops arrived, the Ute attacked the Indian agency, killing Meeker and his 10 male employees. They took some women and children as hostages to secure their own safety as they fled and held them for 23 days.[6][7][8] Two of the women taken captive were of Meeker's family: his wife Arvilla and daughter Josephine, just graduated from college and working as a teacher and physician.

Meeker is buried at the Linn Grove Cemetery, Greeley, Weld County, Colorado.[9]

Legacy and honors

- Meeker, Colorado was named after him.[10]

- Mount Meeker, a shorter neighbor to Longs Peak, the tallest mountain in Rocky Mountain National Park, was named for him.

- The Meeker Home Museum is located at 1324 9th Avenue Greeley, Colorado. It was originally Nathan Meeker's home.

- In 1970, he was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.[11]

Notes

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Guide to the Meeker Manuscript Collection AI-4154 - Biographical Note of Nathan Cook Meeker" (PDF). Greeley Museums. 2015. pp. 1–2. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tucker, Spencer; Arnold, James R.; Wiener, Roberta (September 30, 2011). "Nathan Cook Meeker". The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607–1890: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 482–483. ISBN 978-1-85109-697-8.

- ^ "Guide to the Meeker Manuscript Collection AI-4154 - Biographical Note of Arvilla Delight Smith Meeker" (PDF). Greeley Museums. 2015. pp. 3–4. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ Cooling, Benjamin Franklin (2003). Forts Henry and Donelson: The Key to the Confederate Heartland. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. pp. 213, 215. ISBN 9781572332652.

- ^ a b "Meeker (Nathan C.) Home". Survey of Historic Sites and Homes: Colorado. National Park Service. 2005. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ^ Jerry Keenan (1997). "Meeker Massacre". Encyclopedia of American Indian Wars: 1492-1890. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio.

- ^ "Milk Creek battlefield". National Park Service, US Department of the Interior. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ "Milk Creek battle (or Meeker Massacre)". Meeker Colorado Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on November 17, 2007. Retrieved March 16, 2008.

- ^ Greeley History

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 204.

- ^ "Hall of Great Westerners". National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

Further reading

- Silbernagel, Robert (2011). Troubled Trails: The Meeker Affair and the Expulsion of the Utes from Colorado. ISBN 978-1-60781-129-9

External links

- "The Last Major Indian Uprising: THE MEEKER MASSACRE AND THE BATTLE OF MILK CREEK", White River Museum, Meeker, Colorado Website (http://www.rioblancocounty.org/)

- "Meeker Home Museum", Greeley, Colorado Website

- "Meeker Family History", Greeley, Colorado Website