Vadim Kirpichenko

Vadim Kirpichenko | |

|---|---|

| Born | 25 September 1922 Kursk, Kursk Oblast, Russian SFSR, USSR |

| Died | 3 December 2005 (aged 83) |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | KGB Foreign Intelligence Service |

| Rank | General Lieutenant |

| Commands | Specialists in Afghanistan in 1979 |

| Battles / wars | Second World War Operation Storm-333 |

| Awards | Order "For Merit to the Fatherland" Fourth Class Order of Lenin Order of the October Revolution Order of the Red Banner (twice) Order of the Patriotic War First Class Order of the Red Star Order of the Badge of Honour Medal "For Courage" |

| Spouse(s) | Valeriya Kirpichenko |

| Children | Sergei Kirpichenko |

Vadim Alekseyevich Kirpichenko (Russian: Вадим Алексеевич Кирпиченко, 25 September 1922 – 3 December 2005) was a Russian officer of the First Chief Directorate of the KGB and its successor, the Foreign Intelligence Service. He served as resident in various countries and rose to First Deputy Head of the First Chief Directorate with the rank of General Lieutenant.

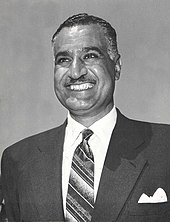

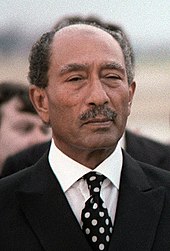

Born in 1922, Kirpichenko initially trained to be a pilot, but with the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union, he enlisted in the Red Army and served in Eastern and Central Europe during the closing stages of the war. Demobilised in 1946, he undertook studies at the Arab branch of the Moscow Institute of Oriental Studies, and was then recruited into intelligence work with the KGB's First Chief Directorate. He began his overseas postings with a period in Egypt as the KGB's deputy resident. This came during the early administration of Gamal Abdel Nasser, and Kirpichenko worked to gather information on its intentions. He passed information back to Moscow during the Suez Crisis in 1956, and worked to establish diplomatic relations with Yemen, before being recalled to the USSR in 1960. He returned to overseas postings in 1962 as resident in Tunisia, with a further period in the USSR between 1964 and 1970, serving as head of the African Department of the First Chief Directorate from 1967. Kirpichenko returned to Egypt in 1970 as resident, and served during the Yom Kippur War. He warned Moscow that Egyptian President Anwar Sadat was planning to reorient his foreign policy away from the Soviet Union and towards the USA. His predictions were unwelcome to the Soviet leadership, but were ultimately proved accurate.

On Kirpichenko's return to the USSR in 1974 he was appointed deputy head of the First Chief Directorate and placed in charge of Department "S", illegal KGB intelligence gathering, and in 1979 he became First Deputy Head of the First Chief Directorate, a post he would hold for the remainder of the existence of the Soviet Union. In late 1979 he was sent to Afghanistan to direct KGB operations surrounding Operation Storm-333, and the beginning of Soviet intervention in the country. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Kirpichenko became head of a group of consultants under the director of one of the KGB's successors, the Foreign Intelligence Service. After retiring in 1997, he worked with others on a six-volume history of Russian intelligence, wrote two books of his own, and lectured widely on intelligence matters. Over the course of his career he received 54 awards from the Soviet, Russian and foreign governments. He died in 2005, survived by his wife, Valeriya Nikolaevna, an academic specialising in Arabic literature. Their son, Sergei Vadimovich, was a prominent diplomat in the Arab world, serving as ambassador to several Middle Eastern countries, including to Egypt, where his father had served as KGB resident for a number of years.

Early life and wartime service

Kirpichenko was born on 25 September 1922 in Kursk, Kursk Oblast, part of the Russian SFSR, in the USSR.[1][2] He attended the No. 4 Air Force Special School, which provided primary flight training alongside the usual secondary education.[3] He went on to attend the Zhukovsky Air Force Engineering Academy, but the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 interrupted his studies.[3] He joined the 103rd Guards Rifle Division in January 1945, seeing action in the closing stages of the war, in Hungary, Austria and Czechoslovakia, and at the Balaton Defensive Operation in March that year.[3] During his wartime service he was awarded the Medal "For Courage", for his part in the Vienna Offensive.[1][3][4] His unit remained in action until the surrender of Axis forces in Czechoslovakia on 12 May 1945.[4]

Intelligence training

Kirpichenko left the army at the end of 1946 with the rank of senior sergeant, and enrolled in the Moscow Institute of Oriental Studies, where he studied in the Arab branch.[1][2] He graduated as the highest scoring student, and had been secretary of the institute's party committee. He was then offered the chance to become an intelligence officer. He enrolled in Intelligence School No. 101 on 1 September 1952, where he learned the basics of the intelligence profession, alongside Arabic and French.[1][2][3] With the completion of his studies in July 1953, he joined the Eastern Department of the KGB's First Chief Directorate, which was responsible for foreign operations and intelligence activities.[1] He was assigned the code name "Vadimov".[5]

Overseas postings

His first overseas posting was to Egypt in December 1954 as the KGB's deputy resident, where he was based until 1960.[2][3] On his arrival in Egypt he found that he was not familiar with the local dialect, and spent the next one and a half years in intensive language study alongside his intelligence duties.[4] His arrival coincided with the early period of Gamal Abdel Nasser's rule, with the Soviet authorities particularly concerned about the new government's stance towards the Western powers, and its intentions in the Arab world. Kirpichenko worked to develop intelligence sources and pass information back to the Soviet Union. When Dmitri Shepilov, Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, visited Egypt in May 1956, it was Kirpichenko who arranged a meeting between Nasser and Shepilov, using his contacts in Nasser's powerbase, the Free Officers Movement.[4]

During the Suez Crisis in October and November 1956, Kirpichenko remained in Cairo and continued to gather intelligence.[4] Despite Western opinion that the Soviet Union was behind Nasser's nationalisation of the Suez Canal, Kirpichenko noted that "we did not have any specific information about Nasser's intentions, but we always indicated in our reports that such a step was possible at any moment".[6] Despite not having informed Moscow of their intentions, Kirpichenko reported that the general feeling among Egyptians was that the Soviet Union should come to their aid once fighting began. "The first days passed and our situation became grim. Agitated Egyptians, waving their fists, cried "Russians, where are you! Where are your airplanes? Where are your weapons? Where are your soldiers? Why isn't Russia saving Egypt?" I didn't understand these demands back then, but later on, after experiencing two further wars in Egypt, I stopped being amazed at these outcries."[6]

In December 1958 he accompanied Nasser on his visit to the Soviet Union, and acted as a translator during Nasser's meetings with Nikita Khrushchev.[4] Kirpichenko was also one of the diplomats involved in the establishment of diplomatic relations with Yemen.[4] He did this by cultivating a friendship with Crown Prince Muhammad al-Badr, that was close enough that the Prince reportedly refused to visit London in 1957 without Kirpichenko at his side.[7] Kirpichenko returned to the Soviet Union in 1960 and spent two years working with the KGB's central organisation, before moving to Tunisia as resident in February 1962. Here he was tasked with maintaining contacts with the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic, the political arm of the National Liberation Front during the Algerian War.[4] This posting lasted until August 1964.[1][2][3]

Returning once more to the Soviet Union, he spent between 1964 and 1967 with the central organisation.[2] In 1967 he was appointed head of the African Department of the First Chief Directorate, holding this position until 1970.[2] During this time he made visits to Syria, Yemen, Ethiopia, Angola, Libya, Algeria and Tunisia.[4] Kirpichenko returned to Egypt in 1970, becoming foreign intelligence resident there until 1974.[2][8] He was in post during the Yom Kippur War between Egypt and Israel in 1973, and subsequently warned Soviet leaders that Egyptian president Anwar Sadat was planning to reorient Egyptian foreign policy away from the Soviet Union and towards the United States, having learnt that Sadat had been in secret communication with US President Richard Nixon.[4] This view was at odds with the general opinion of Soviet leaders, who considered Sadat a loyal friend of the Soviet Union, and successor to Nasser's political legacy. Subsequent developments were to vindicate Kirpichenko.[4] As with the Suez Crisis, there were suspicions in Western capitals that the Soviet Union was behind Egypt's actions. Kirpichenko instead argued that the Soviet Union had tried to prevent an Egyptian offensive that risked destabilising the region.[9] He was promoted to Major General in 1973, and to General Lieutenant in 1980.[3]

His good service brought him to the attention of Yuri Andropov, chairman of the KGB, and in 1974 he was appointed deputy head of the First Chief Directorate and led Department "S", illegal KGB intelligence gathering, where he spent the next five years.[1][2] In 1979 Kirpichenko became First Deputy Head of the First Chief Directorate, and would hold this position until 1991.[1][2][8]

Afghanistan

On 4 December 1979 Kirpichenko arrived in Kabul, in Afghanistan, with a group of officers of the Soviet Airborne Forces, having been sent by KGB chairman Vladimir Kryuchkov to plan for the removal of Hafizullah Amin, the sitting Chairman of the Presidium of the Revolutionary Council of Afghanistan.[1][4][10] He took charge of the intelligence officials in the country in preparation for Operation Storm-333, the ousting of Amin and the installation of Babrak Karmal as Chairman of the Presidium of the Revolutionary Council.[2] At a meeting at Kabul airport on 26 December 1979 Kirpichenko oversaw the inclusion of KGB reconnaissance and sabotage units with the 103rd Guards Airborne Division, with orders to direct elements of the division to key Afghan institutions, which were to be secured for the new government.[4] The planning for the operation took place in great secrecy, with even the newly appointed Soviet ambassador, Fikryat Tabeyev, unaware of the operation until after it had begun. Tabeyev telephoned Kirpichenko asking for explanations, but Kirpichenko replied that he was too busy at the time, but promised to report in the morning.[11]

Late and Post-Soviet period

From 1 October 1988 to 6 February 1989 Kirpichenko served as chief of foreign intelligence.[2] In June 1991 Kirpichenko warned against the effects of Glasnost, which he claimed were making it easier for foreign intelligence agents to work successfully in the USSR.[5] In 1991, with the dissolution of the Soviet Union and subsequent restructuring of the intelligence services, Kirpichenko was appointed head of a group of consultants under the director of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service.[1] He retired from this in 1997, and began working with a number of authors as assistant editor-in-chief to compile a six-volume Essays on the History of Russian Intelligence.[1] He lectured widely on this topic, in the US, UK, Bulgaria, Switzerland, Malta, South Korea and France, and attended numerous international conferences and seminars on the history of intelligence.[1] He published two books; From the Intelligence Archives (Russian: Из архива разведчика, Iz arkhiva razvedchika) and Intelligence: People and Personalities (Russian: Разведка: лица и личности, Razvedka: litsa i lichnosti), and numerous articles and essays on intelligence matters.[4][12][13] He was an honorary professor of the Academy of Foreign Intelligence.[4]

Awards and honours

Over his career Kirpichenko received many awards and decorations.[1] He held eight Soviet and Russian orders, including the Order "For Merit to the Fatherland" Fourth Class, the Orders of Lenin, October Revolution, Red Star, Patriotic War First Class, and the Badge of Honour.[2] He was twice awarded the Order of the Red Banner.[2] He received the badges "Honorary State Security Officer" and "For Service in Intelligence", and had received honours from eight foreign governments, including Vietnam, Peru, Mongolia, the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen, the German Democratic Republic and Afghanistan.[1][2] He was awarded the Prize of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Russia in the field of literature and art.[12] He was also an Honorary Citizen of Kursk.[12] In total he had 54 awards.[1]

Family and death

Kirpichenko died on 3 December 2005.[1][2] His wife, Valeriya Nikolaevna, was a philologist and specialist in Arabic literature with the Institute of Oriental Studies at the Russian Academy of Sciences. She outlived him, dying in 2015.[14] Their son, Sergei Vadimovich, was born in 1951, and like his parents specialised in Middle Eastern affairs. He became a diplomat, and served as ambassador to the United Arab Emirates, Libya, Syria and Egypt.[14][15]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Исполняется 85 лет со дня рождения легендарного разведчика Кирпиченко" (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 25 September 2007. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Кирпиченко Вадим Алексеевич" (in Russian). Foreign Intelligence Service. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "КИРПИЧЕНКО Вадим Алексеевич" (in Russian). shieldandsword.mozohin.ru. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o КИРПИЧЕНКО Вадим Алексеевич (1922–2005) at the Wayback Machine (archived 1 December 2007)

- ^ a b Andrew, Christopher; Gordievsky, Oleg (1992). More 'instructions from the Centre': Top Secret Files on KGB Global Operations, 1975-1985. Psychology Press. pp. 125–128. ISBN 9780714634753.

- ^ a b Ro'i, Yaacov; Morozov, Boris (2008). The Soviet Union and the June 1967 Six Day War. Stanford University Press. pp. 68–70. ISBN 9780804758802.

- ^ Ferris, Jesse (2013). Nasser's Gamble: How Intervention in Yemen Caused the Six-Day War and the Decline of Egyptian Power. Princeton University Press. pp. 74–75. ISBN 9780691155142.

- ^ a b Pringle, Robert W. (2015). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 161. ISBN 9781442253186.

- ^ Ro'i, Yaacov; Morozov, Boris (2008). The Soviet Union and the June 1967 Six Day War. Stanford University Press. p. 236. ISBN 9780804758802.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2011). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–89. Oxford University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-19-983265-1.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2011). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–89. Oxford University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-19-983265-1.

- ^ a b c Antonov, V. S. (2013). Служба внешней разведки. История, люди, факты (in Russian). Moscow. pp. 79–80, 253.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Кирпиченко Вадим Алексеевич" (in Russian). eurasian-defence.ru. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Биография Сергея Кирпиченко". tass.ru (in Russian). TASS. 2 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ "Умер посол России в Египте Сергей Кирпиченко". ria.ru (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 2 September 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- 1922 births

- 2005 deaths

- KGB officers

- Soviet spies

- People from Kursk

- Personnel of the Soviet Airborne Forces

- Soviet military personnel of the Soviet–Afghan War

- Soviet military personnel of World War II

- Recipients of the Order of Lenin

- Recipients of the Medal "For Courage" (Russia)

- Recipients of the Order "For Merit to the Fatherland", 4th class

- Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner

- Kirpichenko family