O.W. Gurley

O.W. Gurley | |

|---|---|

| Born | Ottowa W. Gurley December 25, 1868 |

| Died | c. 1935 |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Businessman and real-estate developer |

| Known for | Greenwood District, Tulsa, aka "Black Wall Street" |

O. W. Gurley (born Ottowa W. Gurley; 25 December 1868 – c. 1935) was once one of the wealthiest Black men and a founder of the Greenwood district in Tulsa, Oklahoma, known as "Black Wall Street".[1][2]

Early life

Gurley was born in Huntsville, Alabama to John and Rosanna Gurley, formerly enslaved persons, and grew up in Pine Bluff, Arkansas.[1]: 128 After attending public schools[1] and self-educating,[3] he worked as a teacher and in the postal service.[1]: 128 .[3] In 1889, he came to what was then known as Indian Territory to participate in the Oklahoma Land Rush, staking a claim in what would be known as Perry, Oklahoma.[3] The young entrepreneur had just resigned from an appointment under president Grover Cleveland in order to strike out on his own."[4] In Perry he rose quickly, running unsuccessfully for treasurer of Noble County at first, but later becoming principal at the town’s school and eventually starting and operating a general store for 10 years.[3]

Greenwood District

In 1905, Gurley sold his store and land in Perry and moved with his wife, Emma, to the oil boomtown of Tulsa, where he purchased 40 acres of land which was "only to be sold to colored."[3][4][1]: 194 The first law passed in the new State of Oklahoma, 33 days after statehood, set in place a Jim Crow system of legally enforced segregation, and required blacks and whites to live in separate areas.[5] However, Oklahoma was considered a significant economic and social opportunity by Gurley, politician Edward P. McCabe and others, leading to the establishment of 50 all-black towns and settlements, among the highest of any state or territory.[6]

Among Gurley's first businesses was a rooming house which was located on a dusty trail near the railroad tracks. This road was given the name Greenwood Avenue, named for a city in Mississippi. The area became very popular among black migrants fleeing the oppression in Mississippi. They would find refuge in Gurley's building, as the racial persecution from the south was non-existent on Greenwood Avenue. On the contrary, Greenwood was later dubbed Black Wall Street as it became increasingly self-sustained and catered to upwardly mobile Black people.[7] Gurley also provided monetary loans to Black people wanting to start their own businesses.[7]

In addition to his rooming house, Gurley built three two-story buildings and five residences and bought an 80-acre (32 ha) farm in Rogers County. Gurley also founded what is today Vernon AME Church.[8] He also helped build a black Masonic lodge and an employment agency.[1]

This implementation of "colored" segregation set the Greenwood boundaries of separation that still exist: Pine Street to the north, Archer Street and the Frisco tracks to the south, Cincinnati Street on the west, and Lansing Street on the east.[8]

Gurley formed an informal partnership with another Black American entrepreneur, J.B. Stradford, who arrived in Tulsa in 1899, and they developed Greenwood in concert.[1]: 194 In 1914, Gurley's net worth was reported to be $150,000 (about $3 million in 2018 dollars).[1] And he was made a sheriff's deputy by the city of Tulsa to police Greenwood's residents, which resulted in some viewing him with suspicion.[1] By 1921, Gurley owned more than one hundred properties in Greenwood and had an estimated net worth between $500,000 and $1 million (between $6.8 million and $13.6 million in 2018 dollars).[1]

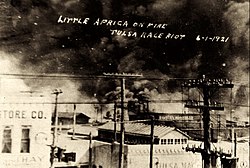

Gurley's prominence and wealth were short lived, and his position as a sheriff's deputy did not protect him during the race massacre. In a matter of moments, he lost everything. During the race massacre, The Gurley Hotel at 112 N. Greenwood, the street's first commercial enterprise as well as the Gurley family home, valued at $55,000, was lost, and with it Brunswick Billiard Parlor and Dock Eastmand & Hughes Cafe.[9] Gurley also owned a two-story building at 119 N. Greenwood. It housed Carter's Barbershop, Hardy Rooms, a pool hall, and cigar store. All were reduced to ruins. By his account and court records, he lost nearly $200,000 in the 1921 race massacre.[8]

Later life

Because of his leadership role in creating this self-sustaining exclusive black "enclave," it has been rumored that Gurley was lynched by a white mob and buried in an unmarked grave. However, according to the memoirs of Greenwood pioneer, B.C. Franklin,[10] Gurley left Greenwood for Los Angeles, California.[1] Gurley and his wife, Emma, moved to a 4-bedroom home in South Los Angeles and ran a small hotel.[1] He was honored in a 2009 documentary film called, Before They Die! The Road to Reparations for the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Survivors.[11]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Wills, Shomari (2018). Black Fortunes. New York, NY: HarperCollins. pp. 195, 196, 243, 252, 264. ISBN 978-0-06-243760-0.

- ^ Hill, Larry; Gara Forbes, Antoine; Gerda, Janice; Sapp, Karen. "O. W. Gurley | Black Wall Street USA". blackwallstreet.org. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Gara, Antoine. "The Bezos Of Black Wall Street". Forbes. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b Lori Latrice Sykes, Making the System Work for You: The Alexander Norton Story, M&B Visionaries (2008) ISBN 0-615-19355-2

- ^ O'Dell, Larry. "Senate Bill One | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture". www.okhistory.org. Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Schmidt, Heidi. "The History of African American Towns in Oklahoma" (PDF). Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b Clark, Alexis. "Tulsa's 'Black Wall Street' Flourished as a Self-Contained Hub in Early 1900s". HISTORY. Retrieved 2020-08-17.

- ^ a b c James S. Hirsch, Riot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race War and Its Legacy, Houghton Mifflin (2002) ISBN 0-618-10813-0

- ^ Staples, Brent (19 December 1999). "Unearthing a Riot". The New York Times. Section 6. p. 64. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ John Hope Franklin and John Whittington Franklin, eds., My Life and an Era, the Autobiography of Buck Colbert Franklin, Louisiana State University Press (1998) ISBN 0-8071-2213-0

- ^ Before They Die! The Road to Reparations for the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Survivors.