League of Peace and Freedom

The Ligue internationale de la paix (League of Peace and Freedom) was created after a public opinion campaign against a war between the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia over Luxembourg. The Luxembourg crisis was peacefully resolved in 1867 by the Treaty of London but in 1870 the Franco-Prussian War could not be prevented so the league dissolved and refounded as the 'Société française pour l'arbitrage entre nations' (League of arbitration between the Nations) in the same year.

The Société française pour l'arbitrage entre nations can be seen as a precursor of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, founded with the first Hague Peace Conference in 1899, and a precursor of the League of Nations, founded with the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 and followed by the United Nations. The establishment of the Permanent Court of Arbitration was also set up by the Inter-Parliamentary Union that Frédéric Passy founded together with William Randal Cremer in 1889.

History

The first "Society of Peace" was created in 1830 by Jean-Jacques de Sellon. Several people from various countries meet between the Allaman Castle and Geneva at the initiative of Sellon's account, who then founded the “Société de la Paix de Genève”. Jean-Jacques de Sellon started from the principle of the inviolability of the human person, which led him first to lead a campaign for the abolition of slavery and the death penalty, then to devote himself to propaganda in favor of peace and arbitration between nations.

The first European Peace Congress, convened by the London Peace Society on the initiative of the American Peace Society, met in London in 1843.[1]

A congress was held in Brussels in 1848 then - chaired by Victor Hugo - in Paris from August 22 to 24, 1849. Next came the congresses in Frankfurt am Main in 1850, then in London in 1851.

The year 1867 was marked by strong international tension, after the victory of Prussia over Austria in the Austro-Prussian War: France and Prussia were on the verge of war. Frédéric Passy, journalist at Le Temps, led a campaign against this war, as did, for example, Evariste Mangin, director of the Nantes newspaper Le Phare de la Loire. On May 30, 1867, Frédéric Passy founded the International League of Peace and Freedom in Paris.

Inaugural Congress (1867)

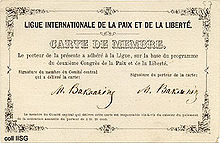

The Inaugural Congress of the League of Peace and Freedom (French: Ligue internationale de la paix et de la liberte) was originally planned for September 5, 1867 in Geneva.[2] Emile Acollas set up the League's Organising Committee, which enlisted the support of John Stuart Mill, Élisée Reclus, and his brother Élie Reclus.

Other notable supporters included contemporary activists, revolutionaries, and intellectuals such as Victor Hugo, Giuseppe Garibaldi, Louis Blanc, Edgar Quinet, Jules Favre, and Alexander Herzen. Ten thousand people from across Europe signed petitions in support of the Congress.[3]

They also counted on the participation of the International Workingmen's Association (IWMA), inviting the sections of the IWMA and its leaders, including Karl Marx, to attend the Congress. They decided to postpone the opening of the Congress until September 9, so as to enable delegates of the Lausanne Congress of the IWMA (to be held on September 2–8) to take part.

While the balloting was going on, Citizen Marx called attention to the Peace Congress to be held in Geneva. He said: It was desirable that as many delegates as could make it convenient should attend the Peace Congress in their individual capacity; but that it would be injudicious to take part officially as representatives of the International Association. The International Working Men’s Congress was in itself a peace congress, as the union of the working classes of the different countries must ultimately make international wars impossible. If the promoters of the Geneva Peace Congress really understood the question at issue they ought to have joined the International Association. [From The Bee-Hive Newspaper August 17, 1867, reporting on a meeting of the IWMA Central Council.]

The anarchist Mikhail Bakunin also played a prominent role in the Geneva Conference, and joined the Central Committee.[4] The founding conference was attended by 6,000 people. As Bakunin rose to speak:

the cry passed from mouth to mouth: "Bakunin!" Garibaldi, who was in the chair, stood up, advanced a few steps and embraced him. This solemn meeting of two old and tried warriors of the revolution produced an astonishing impression .... Everyone rose and there was a prolonged and enthusiastic clapping of hands.[5]

Bern Congress (1868)

The second congress of the League of Peace and Freedom took place in Berne from September 21 to 25, 1868. Invited to be officially represented there, the International Workingmen's Association (IWA) decided a few days earlier, at its Brussels Congress, not to send a delegation there.

The Bern congress was mainly marked by lively debates during the discussion on "the relationship of the economic and social question with that of peace and freedom", between the democratic majority (Gustave Chaudey, Friborg, etc.) and the socialist minority (Mikhail Bakunin, Walery Mroczkowski, Élisée Reclus, Giuseppe Fanelli, Aristide Rey, etc.). The Socialists presented the following resolution:

“Whereas the question which presents itself most urgently to us is that of the economic and social equalization of classes and individuals, Congress affirms that, apart from this equalization, that is to say outside the justice, freedom and peace are not achievable. Accordingly, Congress puts on the agenda the study of practical means of resolving this issue."

At the end of the discussions this resolution was rejected by the congress. On September 25, the socialist minority decided to quit the League for Peace and Freedom and to create the International Alliance of Socialist Democracy.

The Lausanne Congress (1869)

The Bern Congress was nearly the last. The central committee, one of whose main tasks was to prepare the next meeting of the League, performed its mission very poorly and it was the Geneva committee which had to take the initiative for the 3rd Congress. On July 11, 1869, the Lausanne congress saw the election of a new central committee headed by Jules Barni. He proposed the following discussion program: determining the bases of a federal organization for Europe, the problems of the Eastern question and the Polish question in relation to the principles of the League. The committee decided to offer the honorary presidency to Victor Hugo, who officially accepted in a letter of September 5, 1869. It was during this congress that Ferdinand Buisson read a speech which ended with the famous tirade: "children to say to themselves: a uniform is a livery, and any livery is ignominious, that of the priest and that of the soldier, that of the magistrate and that of the lackey."[6]

Dissolution

The league disappeared with the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, then was re-founded under the name of the French Society of Friends of Peace, which became the French Society for Arbitration between Nations.[7] The Society of Arbitration between Nations prefigured the Permanent Court of Arbitration created by Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. It published the magazine United States of Europe.

See also

References

- ^ Durand, André (30 October 1996). "Gustave Moynier et les sociétés de la Paix" (in French). International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Sandi E. Cooper (1991). "Pacifism in France, 1889-1914: International Peace as a Human Right". French Historical Studies. 17 (2): 359–386. doi:10.2307/286462. JSTOR 286462.

- ^ Mark Leier. Bakunin: The Creative Passion. St. Martin's Press: New York, 2006. p. 178.

- ^ Leier, Mark (2006). Bakunin: The Creative Passion. Seven Stories Press. pp. 200–202. ISBN 978-1-58322-894-4.

- ^ Bakunin's idea of revolution & revolutionary organisation published by Workers Solidarity Movement in Red and Black Revolution No.6, Winter 2002.

- ^ Brunet, Martine (2011). "L'unité d'une vie". In Ferdinand Buisson (ed.). Souvenirs et autres écrits. Collection Libres pensées protestante. Théolib. p. 119-170. ISBN 978-2-36500-150-2. OCLC 1017608270.

- ^ Les parlementaires de la Seine sous la Troisième République: Etudes, Volume 1 (in French). Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne. 2001. p. 455. ISBN 2859444327. OCLC 718619156.