Voice therapy

| Voice therapy | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | phoniatrics |

Voice therapy consists of techniques and procedures that target vocal parameters, such as vocal fold closure, pitch, volume, and quality. This therapy is provided by speech-language pathologists and is primarily used to aid in the management of voice disorders,[1] or for altering the overall quality of voice, as in the case of transgender voice therapy. Vocal pedagogy is a related field to alter voice for the purpose of singing. Voice therapy may also serve to teach preventive measures such as vocal hygiene and other safe speaking or singing practices.[2]

Orientations

There are several orientations towards management in voice therapy. The approach taken to voice therapy varies between individuals, as no set treatment method applies for all individuals.[3] The specific method of treatment should consider the type and severity of the disorder, as well as individual qualities such as personal and cultural characteristics.[4] Some common orientations are described below.

Symptomatic

Symptomatic voice therapy aims to directly or indirectly modify the symptoms that are caused by a voice disorder.[5][6][4] Techniques are implemented to facilitate the production and maintenance of a voice that is most appropriate for the individual.[6] Symptomatic voice therapy can modify respiration, phonation, resonance, voice, loudness, rate, and laryngeal muscle tension and may assist in gender reassignment voice change.[6]

Physiologic

Physiologic voice therapy may be adopted when the voice disorder is caused by a disturbance in the physiology of the vocal mechanism.[5][6] Therapy directly modifies the abnormal physiologic activity affecting respiration, phonation, and resonance.[6][4] Physiologic voice therapy aims to create a balance between the various subsystems.[4]

Hygienic

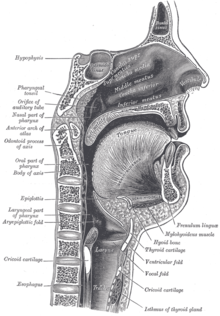

Hygienic voice therapy involves modifying or eliminating inappropriate vocal behaviours that lead to voice dysfunction. Once behaviours are modified, the voice may improve towards a normal state.[5][6] The voice is improved without directly targeting physiological mechanisms.[6] Hygienic Voice therapy uses different techniques which are used for both management and prevention for voice disorders. For management of disorders, hygienic voice therapy is usually used in conjunction with other voice therapy methods. Vocal hygiene programs can include many different components but usually includes speech and non-speech aspects. Speech aspects include addressing loudness and amount of use. Whereas non-speech components typically address components such as allergies, or laryngopharyngeal reflux. A vocal hygiene program also may include a component about learning about how the voice works (e.g. anatomy and physiology).[7]

Some vocal hygiene guidelines for better vocal health:

- Avoid phono-traumatic behaviours (i.e. throat clearing, yelling, cheering, excessive crying, talking over extensive background noise, and increase use voice amplification when appropriate).

- Decrease or eliminate use of alcohol, caffeine, and drugs (i.e. tobacco, recreational drugs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and aspirin).

- Increase humidification of the upper respiratory tract (i.e. drink more water, increase environmental humidity when possible, and decrease time spent in dry or dusty environments).

- Decrease quantity of speech (if you're an excessive voice user or post laryngeal surgery).[5][8]

Psychogenic

Psychogenic voice therapy examines the psychological and emotional factors that cause and perpetuate disordered voice, and focuses on modifying those factors to improve voice functioning.[5][6]

Eclectic

The various voice therapy orientations are not exclusive of each other. Any combination of orientations can be used in treatment. This is known as eclectic voice therapy.[5][6]

Procedures

Vocal surgeries

While hormone replacement therapy and gender reassignment surgery can cause a more feminine physical appearance, they do little to alter the pitch or sound of the voice. A number of surgical procedures exist to alter the vocal structure. These can be used in conjunction with voice therapy:

- Cricothyroid approximation (CTA) (is the most common)

- Laryngoplasty

- Thyrohyoid approximation

- Laryngeal reduction surgery (surgical shortening of the vocal cords)

- Laser assisted voice adjustment (LAVA)

Voice prosthesis

Voice prosthesis is an artificial device, usually made of silicone, that is used to help laryngectomized patients to speak.

Applications

Physiologic voice therapy

Accent Method

There are many different physiologic voice therapy approaches that can be used in treatment.[9] An example of a holistic approach used in voice therapy is the Smith Accent Method, introduced as a method to improve both speech and voice production. This technique can be used to treat stuttering, breathing, dysprosody, dysphonia, and to increase control of breathing, phrasing, and rhythm.[10]

The main targets of accent methods are:

- To increase the pulmonary output

- To reduce tension in muscles

- To reduce glottis waste

- To stabilize the vibratory pattern of the vocal folds while speaking.[11][12]

The accent method is implemented two to three times a week, in 20 minute sessions. The procedure is two-part: diaphragmatic breathing and rhythmic vowel play. During diaphragmatic breathing, the patient is trained to elicit and monitor abdominal breathing and muscle relaxation. Rhythms are then introduced in two beats, with an accent on the second sound. The accented rhythm is then generalized to longer phonation at three speeds (largo, andante, and allegro), while maintaining proper breathing techniques. The rhythms are then generalized to real speech, through the use of repetition, reading passages, conversations, and monologues.[12][11]

Symptomatic Voice Therapy

Chant-Talk

There is a wide variety of treatments that fall under symptomatic voice therapy.[9] An example of a symptomatic voice treatment method is the chant-talk approach. The chant-talk approach uses pre-existing characteristics found in chanting-styled music, such as rhythm and prosodic patterns. The therapy is used to reduce phonatory effort, which causes vocal fatigue.[9] Chant therapy is used to minimize hyperfunctionality by affecting loudness and voice quality. The technique employs the continuous tone quality found in music chanting. More specifically, it elevates the pitch of the voice during phonation, prolongs the vowels, de-stresses syllables, and lessens word-initial glottal attacks.[13]

The goals of the chant-talk approach are to use voice quality and pitch techniques to decrease the effort used while talking. The technique is first demonstrated through the use of recordings, with the patient subsequently asked to imitate the specified voicing patterns. Once the chant has been mastered, the patient is asked to read aloud in chant and in normal register in 20 second alternation. Patients are asked to reduce chanting to a minimal, while maintaining vowel prolongations and softened glottal word onsets. Sessions are recorded in order to provide auditory feedback.[13]

Resonant Voice Therapy

Resonant voice is a technique often taught to actors and singers to improve voice production.[8] Resonant voice therapy teaches clients to use resonant voice in order to reduce vocal fold trauma. Resonant voice is produced with minimally adducted (closed) vocal folds. This technique reduces the force of the vocal folds vibrating against each other, which reduces trauma and allows healing.[14] A variety of different programs, including Lessac-Masden Resonant Voice Therapy (LMRVT), Humming, and Y-Buzz, have been studied and used to help teach resonant voice.[14]

Each program uses slightly different strategies to teach resonant voice. However, they all have similar hierarchical structures and share the goal of producing a strong, clear voice with minimal effort.[14] In the aforementioned programs, the client begins by trying to produce resonance during nasal consonants and vowels, then progresses to using this technique in words, sentences, and conversations.[14] During voice therapy, clinicians often help patients conceptualize resonant voice by discussing where the patient "feels" their voice. Patients with dysphonia often describe their voices as vibrating in the throat.[8] Resonant voice is described as vibrating higher and further forward, and being felt at the alveolar ridge and in the maxillary bones.[14]

Range Expansion and Stabilization Techniques (REST) and Exercises

Range Expansion and Stabilization Techniques (REST) and exercises target symptoms such as reduced pitch range, reduced loudness, and voice instability which are often related to a variety of different voice disorders.[15] There are three main exercises that work to target these symptoms. The first is called a “stretching” exercise and targets pitch range. The client is asked to find their comfortable pitch, and then slowly go up 1/3 of an octave using a gliding technique, and then gently go back to their comfortable pitch on one inhale. This procedure is followed by an exhale and rest for 1–2 seconds, then should be repeated 2-3 times. As the client improves, octave levels can be increased. The second is called a “resistance” exercise and focuses on loudness. The client is asked to use their comfortable pitch and go from a soft to loud voice for 3–4 seconds, followed by an exhale. It is important to train the client to do this without straining their voice. The third is called an “endurance” exercise, the client is instructed to hold a note as long as they can by controlling their exhale (this should be done with 3-4 comfortable pitches).[8]

Vocal pedagogy

Vocal pedagogy for singing, particularly opera

- Dialect training for actors who need to speak with a particular dialect or accent

While many transgender women wish to sing like cisgender women, it will require a lot of training for one to achieve a feminine-sounding voice. This is why most who haven't gone through male puberty begin hormone replacement therapy have a higher chance of retaining this quality. See castrato for more information.

Voice therapy in transgender individuals

Non-surgical techniques undertaken by trans women and trans men as a part of gender transition to make the perceived gender of their voices match their gender.[16] Voice feminization is the desired outcome of surgical techniques, speech therapy, self-help programs and a general litany of other techniques to acquire a female-sounding voice from a perceived male-sounding voice. Voice masculinization is the use of the same procedures and techniques to acquire a male-sounding voice.

Voice management after laryngectomy

- Some laryngectomized patients may succeed in achieving communication through the use of esophageal speech, in which air is swallowed, then gradually released while producing speech.[17]

- Others may make use of an electrolarynx (external vibrating device), which produces vibrations in the patient's oral cavity that they can no longer produce themselves without air passing through their vocal folds.[17]

- The current medical standard after a laryngectomy is a tracheoesophageal puncture, which includes the insertion of a voice prosthesis.

Voice therapy with prostheses

A voice prosthesis is an artificial device, usually made of silicone, that is used to help laryngectomized patients speak. A tube is inserted into the neck, below the vocal folds, allowing air to go through the tube instead of through the mouth and nose.[18] Following a total laryngectomy, air will no longer pass through the vocal folds, significantly altering the person's ability to communicate orally.[18] In some instances, the person may be able to block the tube with their fingers and breathe as they did before the surgery or attach a valve to their tube, which serves to allow air to enter while preventing food from passing into the windpipe. In others, this is not a viable option due to resistance, infection, and insufficient air.[18] Voice therapy may then be turned to as a means for a person to regain the ability to communicate orally. Voice prostheses and ventilators may affect the volume of the speaker and the overall quality of the speaker's voice.[18] With the help of voice therapy as well as possible adjustments to ventilator settings, the goal is to become accustomed to using the device functionally and to learn the techniques and skills needed to participate in daily communication.[3]

Other types of speech and language therapy after laryngectomy: Communication strategies

If the person is using a ventilator with their tube, there are long pauses between cycles of the ventilator. During these moments of silence, someone else may begin to speak, thus taking away the turn of the person with a ventilator. The person who has undergone a laryngectomy can use tools and techniques, such as those provided by a Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP) to self-advocate during conversations, in order to ensure that they are given the space that they need to participate in conversation.[3] An SLP can also provide information to the person and to the people who interact with them frequently on communication strategies that would benefit them.[3]

Pediatric Voice Therapy

In children, the voice disorders and dysphonia are quite common, although the reported prevalence varies significantly depending on the type of data collection and the location from which it was drawn. Some estimates suggest a rate between 6 and 38% of school-aged children,[19] others indicate between 2 and 23%.[20] Dysphonia is more common in male children than females during school-age. Conversely, as of 13 years and through to adulthood the disorder is more commonly seen in females.[19][21] Other voice disorders such as vocal nodules, are also common in children, particularly before the onset of puberty with an incidence of 17-30%.[22] The most common vocal pathologies occurring in children are nodules (55-68% of cases) and damage caused by congenital lesions (27-41% of cases).[19][23] Other common pathologies in children include vocal fold cysts and polyps.[20] The presence of dysphonia in children can impact psychological well-being and social functioning both in academic and family life and can significantly influence a child's ability to perform daily functions.[19][20][21] Moreover, pediatric voice disorders may progress into adulthood and consequently negatively affect personal and professional ambitions.[21] As a result of these consequences, the United States have implemented a federal mandate through the Individuals with Disabilities Act which states that children with voice disorders that impact their academic performance are entitled to in-school services.[21] Despite this, the criteria for school based services is up to interpretation, and children with voice disorders have inconsistent access to treatment.[20]

Epidemiology

There are various different types of dysphonia with distinct epidemiologies.

- Acute dysphonia usually triggered by an infectious onset.

- Endocrine pathology induced VT

- Laryngeal conditions that lead to chronic childhood voice disorders.[19]

- Functional voice disorders (i.e. no neurologic/ anatomical etiology) [23][25]

- muscle tension dysphonia, puberphonia/mutational falsetto [23]

Pediatric Voice Team

Pediatric voice therapy involves the collaborative work of often multidisciplinary healthcare practitioners forming the voice-care teams.[20] In pediatric cases, the Speech Language Pathologist (S-LP) is usually the primary treatment provider.[20] His or her work may be facilitated by other team members depending on the issues involved. These include a pediatric otolaryngologist, pulmonologist/allergist and nurses.[20] Additionally, other members of the voice-care team can include general practitioners, surgeons, social workers, occupational therapists, dieticians, gastroenterologists and pharmacists.[20] Voice services can be provided in a number of settings, including hospitals, clinics, schools and personal homes.[20]

Assessment

- Interview: The first step of assessment in childhood dysphonia is the interview. In the interview, the clinician must learn who first noticed the dysphonia, the age of onset (early years/months suggests congenital pathology, school age (3–4 years) suggests acquired pathology), as well as the evolution of the disorder.[19] Variation in the presentation of the disorder can be very helpful in guiding the voice therapy.[19][23] For example, if the voice improved on weekends, this could suggest an underlying problem with vocal behaviour. Similarly, if the voice pathology remained stable or varied significantly regardless of context, it is likely unrelated to vocal effort and suggestive of a congenital malformation of the vocal structure.[19] The interview process also includes the collection of a thorough history which informs the clinician of potential risk factors affecting the child (i.e. prematurity, NICU stay, family history, ENT surgeries, hearing impairment etc.).[19][23] In these instances the clinician should screen for swallowing, pneumologic and digestive impairments which could be contributing to the dysphonia.[19][24] Other important factors to take note of during the interview include the child's personality (i.e. introverted/extroverted, carefree/anxious), how they communicate as well as what their home and school environment is like. All of these factors may contribute to the voice disorder itself, as well as to its impact on the child's social functioning.[19]

Flexible endoscope used for physical examination of the vocal structures. - Voice Function Assessment: A clinical assessment of voice function includes a laryngeal exam, perceptual examination of vocal characteristics, the collection of voice samples (reading, singing, loud voice, prolonged vowels etc.) and the examination of vocal behaviours (posture, balance, face and neck muscle activity, respiratory gestures.[19] It also includes objective instrumental measures of maximum phonation time (MPT), jitter, s/z ratios and other relevant acoustic features (intensity, tone, volume pitch).[19] Qualitative instruments which are used to examine vocal quality include the dysphonia Grade, Roughness, Breathiness, Asthenia and Strain (GRBAS) scale as well as the Consensus Auditory Perceptual Evaluation-Voice (CAPE-V) scale.[23]

- Quality of Life: Additionally, qualitative measures are sometimes used to evaluate the extent to which vocal disorders impact children's social interactions, activities and education. These include the Pediatric Voice Handicap Index (pVHI), the Pediatric Voice Outcome Survey (PVOS) and the Pediatric Voice-Related Quality-of-Life (PVRQOL) instruments.[23][24]

- Physical Examination: the physical examination is performed using rigid or flexible endoscopy in order to examine the physiology of the vocal structures.[19]

Treatment

Diagnosis of a voice disorder must be followed by a physician referral in order for a child to have access to therapy services.[20] Treatment of voice disorders in children can involve a combination of behavioral, pharmacological and surgical methods.[21] Behavioural methods are most commonly used to address dysphonia in children, particularly in the case of vocal nodules.[21]

- Behavioural/ Indirect Treatment Methods: The behavioural approach to treatment uses vocal hygiene as an indirect form of therapy, often supplemented by direct voice production training.[21] This method relies heavily on education and guides children towards the use of vocally safe behaviours, such as hydration.[20] It also explains the need to reduce traumatic behaviours including loud phonation, coughing, imitation of animal and machine noises, hard glottal stops and yelling across long distances.[21] In therapy, children are taught to monitor their vocal behaviour for these signs and are sometimes trained to use an alternative gentle and quiet voice.[21]

- Direct Treatment Methods: Direct treatment methods are used to facilitate the use of normal voice behaviours in children with dysphonia.[20]

- Vocal Function Exercises: designed to improve balance between respiration, phonation and resonance.[20] Exercises include the establishment of correct posture and breathing, increasing the duration of sustained vowels to improve breath support, gliding from low to high pitch to strengthen the cricothyroid muscle and stretch vocal folds, gliding from high to low notes to target the thyroarytenoid musculature, and producing varied notes ( C-D-E-F-G) in order to strengthen laryngeal adduction.[20]

- Resonance Therapy: modified form of Resonance Voice Therapy (RVT) designed for children to help facilitate forward focus through exercises required nasal- oral productions.[20]

- Semiocclusion of the Vocal Tract: methods that implement semiocclusion of the vocal tract are designed to increase efficient voicing thereby lessening the forceful vibrations of the vocal folds and minimizing mechanical trauma.[20] This allows for the training of safe vocal behaviours, and provides opportunity for existing vocal trauma/lesions to heal sufficiently.[20] Flow phonation therapy, straw phonation and lip buzzes are examples of these methods.[20]

- Surgical Methods: surgical treatment for certain vocal pathologies is considered when other methods of management have failed and is rarely performed before puberty.[24] If the vocal use is considered a causal factor, these behaviours must be managed before surgery is performed.[24]

References

- ^ Aronson, Arnold Elvin (2009). Clinical Voice Disorders. Thieme. ISBN 978-1-58890-662-5.

- ^ Boone, Daniel R. (1974-05-01). "Dismissal Criteria in Voice Therapy". Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 39 (2): 133–139. doi:10.1044/jshd.3902.133. ISSN 0022-4677. PMID 4825802.

- ^ a b c d Boone, Daniel R.; McFarlane, Stephen C.; Von Berg, Shelley L.; Zraick, Rickard I. (2010). The Voice and Voice Therapy. Boston: Pearson.

- ^ a b c d "Voice Disorders: Treatment". American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- ^ a b c d e f Stemple, Joseph C.; Hapner, Edie R. (2014). Voice Therapy: Clinical Case Studies. San Diego: Plural Publishing Inc.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Stemple, Joseph C.; Roy, Nelson; Klaben, Bernice K. (2014). Clinical Voice Pathology: Theory and Management. San Diego: Plural Publishing Inc.

- ^ Behlau M, Oliveira G (June 2009). "Vocal hygiene for the voice professional". Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 17 (3): 149–54. doi:10.1097/MOO.0b013e32832af105. ISSN 1068-9508. PMID 19342952. S2CID 38511217.

- ^ a b c d H., Colton, Raymond (2011). Understanding voice problems : a physiological perspective for diagnosis and treatment. Casper, Janina K.,, Leonard, Rebecca (Fourth ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9781609138745. OCLC 660546194.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Voice Disorders: Treatment". American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ^ M. Nasser Kotby, Bibi Fex; Kotby, M. Nasser; Fex, Bibi (1998). "The Accent Method: Behavior readjustment voice therapy". Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology. 23 (1): 39–43. doi:10.1080/140154398434329.

- ^ a b Kotby, M. N.; El-Sady, S. R.; Basiouny, S. E.; Abou-Rass, Y. A.; Hegazi, M. A. (1991-01-01). "Efficacy of the accent method of voice therapy". Journal of Voice. 5 (4): 316–320. doi:10.1016/S0892-1997(05)80062-1.

- ^ a b C., Stemple, Joseph (2014). Clinical voice pathology : theory and management. Roy, Nelson,, Klaben, Bernice (Fifth ed.). San Diego, CA. ISBN 9781597565561. OCLC 985461970.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Boone, Daniel (2014). The voice and voice therapy. McGill Library: Boston : Pearson.

- ^ a b c d e Yiu, Edwin M.-L.; Lo, Marco C.M.; Barrett, Elizabeth A. (2016-10-05). "A systematic review of resonant voice therapy". International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 19 (1): 17–29. doi:10.1080/17549507.2016.1226953. hdl:10722/244406. ISSN 1754-9507. PMID 27705008. S2CID 28961224.

- ^ Drake, K.; Bryans, L.; Schindler, J. (2016). "A Review of Voice Therapy Techniques Employed in Treatment of Dysphonia with and Without Vocal Fold Lesions". Professional Voice Disorders. 4 (3): 168–174. doi:10.1007/s40136-016-0128-y. S2CID 78501778.

- ^ Price, P.J. (1989). "Male and female voice source characteristics: Inverse filtering results". Speech Communication. 8 (3): 261–277. doi:10.1016/0167-6393(89)90005-8 – via PubMED.

- ^ a b Tang, Christopher G.; Sinclair, Catherine F. (2015). "Voice Restoration After Total Laryngectomy". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 48 (4): 687–702. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2015.04.013. PMID 26093944.

- ^ a b c d (ASHA), American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (2004). "Preferred Practice Patterns for the Profession of Speech-Language Pathology". doi:10.1044/policy.pp2004-00191.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Mornet, E.; Coulombeau, B.; Fayoux, P.; Marie, J.-P.; Nicollas, R.; Robert-Rochet, D.; Marianowski, R. (2014). "Assessment of chronic childhood dysphonia". European Annals of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Diseases. 131 (5): 309–312. doi:10.1016/j.anorl.2013.02.001. PMID 24986259.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r N., Kelchner, Lisa (2014). Pediatric voice : a modern, collaborative approach to care. Brehm, Susan Baker,, Weinrich, Barbara Derickson,, De Alarcon, Alessandro. San Diego, California. ISBN 978-1597564625. OCLC 891385910.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i J., Hartnick, Christopher (2010-03-01). Clinical management of children's voice disorders. Boseley, Mark E. San Diego, California. ISBN 9781597567466. OCLC 903957558.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ongkasuwan, Julina; Friedman, Ellen M. (2013-12-01). "Is voice therapy effective in the management of vocal fold nodules in children?". The Laryngoscope. 123 (12): 2930–2931. doi:10.1002/lary.23830. ISSN 1531-4995. PMID 24115028. S2CID 5669986.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Benninger, Michael S.; Murry, Thomas; Michael m. Johns, III (2015-08-17). The performer's voice. Benninger, Michael S.,, Murry, Thomas, 1943-, Johns, Michael M., III (Second ed.). San Diego, CA. ISBN 9781597568821. OCLC 958392132.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f Pediatric ENT. Graham, J. M. (John Malcolm), Scadding, G. K. (Glenis K.), Bull, P. D. Berlin: Springer. 2007. ISBN 9783540330394. OCLC 184986276.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Baker, J. (2016). "Functional voice disorders". Functional Neurologic Disorders. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 139. pp. 389–405. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-801772-2.00034-5. ISBN 9780128017722. PMID 27719859.