Fjäriln vingad syns på Haga

| "Fjäril'n vingad syns på Haga" | |

|---|---|

| Art song by Carl Michael Bellman | |

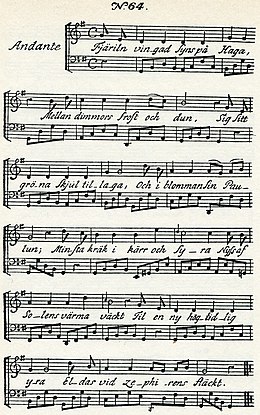

First page of sheet music for 1791 edition | |

| English | The butterfly wingèd's seen in Haga |

| Written | 1770 or 1771 |

| Text | Carl Michael Bellman |

| Language | Swedish |

| Published | 1791 in Fredman's Songs |

| Scoring | voice and cittern |

Fjäril'n vingad syns på Haga (The butterfly wingèd's seen in Haga) is one of Carl Michael Bellman's collection of songs called Fredmans sånger, published in 1791, where it is No. 64. The song describes Haga Park, the attractive natural setting of King Gustav III's never-completed Haga Palace just north of Stockholm. An earlier version of the song was a verse petition to obtain a job for Bellman's wife. The composition is one of the most popular of Bellman's songs, being known by many Swedes by heart. It has been recorded many times from 1904 onwards, and translated into English verse at least four times.

Context

Carl Michael Bellman is a central figure in the Swedish ballad tradition and a powerful influence in Swedish music, known for his 1790 Fredman's Epistles and his 1791 Fredman's Songs.[1] A solo entertainer, he played the cittern, accompanying himself as he performed his songs at the royal court.[2][3][4]

Jean Fredman (1712 or 1713–1767) was a real watchmaker of Bellman's Stockholm. The fictional Fredman, alive after 1767, but without employment, is the supposed narrator in Bellman's epistles and songs.[5] The epistles, written and performed in different styles, from drinking songs and laments to pastorales, paint a complex picture of the life of the city during the 18th century. A frequent theme is the demimonde, with Fredman's cheerfully drunk Order of Bacchus,[6] a loose company of ragged men who favour strong drink and prostitutes. At the same time as depicting this realist side of life, Bellman creates a rococo picture, full of classical allusion, following the French post-Baroque poets. The women, including the beautiful Ulla Winblad, are "nymphs", while Neptune's festive troop of followers and sea-creatures sport in Stockholm's waters.[7] The juxtaposition of elegant and low life is humorous, sometimes burlesque, but always graceful and sympathetic.[2][8] The songs are "most ingeniously" set to their music, which is nearly always borrowed and skilfully adapted.[9]

Song

Music and verse form

Fjäriln vingad is in 4

4 time and is marked Andante. The rhyming pattern is the alternating ABAB-CDCD.[10] Richard Engländer writes that unlike in Bellman's parody songs, the melody is of his own composition.[11]

Lyrics

The song, Bellman's best known, is dedicated to Captain Adolf Ulrik Kirstein, who at the time was Bellman's landlord in Klarabergsgatan, Stockholm.[12] Bellman's biographer Lars Lönnroth states that it was originally a verse petition to baron Gustaf Mauritz Armfelt to get a job for Bellman's wife Lovisa in Haga Palace, and describes the composition as a "royalistic praise text".[13] It was written in 1770 or 1771.[14] The later version of the song omits the Lovisa petition, and describes Haga Park, the attractive natural setting of King Gustav III's never-completed Haga Palace just north of Stockholm.[15]

| Carl Michael Bellman, 1791[16] | Henry Grafton Chapman, 1904[17] | Charles Wharton Stork, 1917[18] | Hendrik Willem van Loon, 1939[19] | Paul Britten Austin, 1977[20] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Fjäriln vingad syns på Haga |

O, a butterfly at Haga, |

Butterflies to Haga faring, |

Butterflies at Haga soaring, |

O'er the misty park of Haga |

-

The song describes King Gustav III's Haga Park. The pavilion here is one of the few parts of his projected palace that were completed.

-

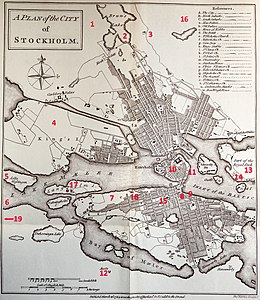

Map of Bellman's Stockholm from William Coxe's Travels into Poland, Russia, Sweden, and Denmark, 1784. Haga park is marked "1".

-

Painting of Carl Michael Bellman entertaining King Gustav III in Haga Park, by Albert Edelfelt, 1884

Reception and legacy

Fjäriln vingad remains popular in Sweden, and is one of the best-known and most often sung of Bellman's songs. It is included in a list of songs that "nearly all [Swedes] can sing unaided".[21] A chime of bells in Solna, near the Haga park described in the song, rings out the melody every hour.[22][23]

An early recording was made by Gustaf Adolf Lund in Stockholm in 1904.[24] Johanna Grüssner and Mika Pohjola recorded it in a medley with "Glimmande nymf" on their song album Nu blir sommar in 2006.[25] In the Zecchino d'Oro in 2005, it was recorded with the Italian title Il mio cuore è un gran pallone.[26]

The song has been translated into English by Henry Grafton Chapman III,[17] Charles Wharton Stork,[18] Helen Asbury,[27] Noel Wirén,[28] and Paul Britten Austin.[29] It has been recorded in English by William Clauson,[30] Martin Best,[31][32] Barbro Strid,[33] and Martin Bagge.[34]

References

- ^ Bellman 1790.

- ^ a b "Carl Michael Bellmans liv och verk. En minibiografi (The Life and Works of Carl Michael Bellman. A Short Biography)" (in Swedish). Bellman Society. Archived from the original on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ "Bellman in Mariefred". The Royal Palaces [of Sweden]. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Anna (1989). "Stockholm in the Gustavian Era". In Zaslaw, Neal (ed.). The Classical Era: from the 1740s to the end of the 18th century. Macmillan. pp. 327–349. ISBN 978-0131369207.

- ^ Britten Austin 1967, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Britten Austin 1967, p. 39.

- ^ Britten Austin 1967, pp. 81–83, 108.

- ^ Britten Austin 1967, pp. 71–72 "In a tissue of dramatic antitheses—furious realism and graceful elegance, details of low-life and mythological embellishments, emotional immediacy and ironic detachment, humour and melancholy—the poet presents what might be called a fragmentary chronicle of the seedy fringe of Stockholm life in the 'sixties.".

- ^ Britten Austin 1967, p. 63.

- ^ Hassler & Dahl 1989, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Engländer, Richard (1956). "Bellmans musikalisk-poetiska teknik" [Bellman's Musical-Poetic Technique] (PDF). Samlaren: Tidskrift för svensk litteraturvetenskaplig forskning (in Swedish): 143–154.

- ^ Burman 2019, pp. 430, 500.

- ^ Lönnroth 2005, pp. 221, 339, 343–348.

- ^ Massengale 1979, p. 198.

- ^ "Haga rustas för kungligt familjeliv". Populär Historia (in Swedish). 9 November 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Hassler & Dahl 1989, p. 233.

- ^ a b Chapman 1904, pp. 88–89.

- ^ a b Anthology of Swedish Lyrics, 1750-1915, trans. by Charles Wharton Stork, (New York: The American-Scandinavian Foundation, 1917). Pages 14–15

- ^ Van Loon & Castagnetta 1939, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Britten Austin 1977, p. 142.

- ^ Berglund, Anders. "100 sånger - som (nästan) alla kan utantill!" [100 songs – that (almost) everyone knows by heart!] (PDF) (in Swedish). Musik att minnas. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Couldry, Nick; McCarthy, Anna (23 November 2004). MediaSpace: Place, Scale and Culture in a Media Age. Routledge. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-134-43635-4.

- ^ Rundkvist, Martin (25 August 2007). "Carl Michael Bellman's Butterfly". Aardvarchaeology. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ "Fjäriln vingad syns på Haga / sjungen af operettsångaren G. A. Lund, Stockholm" [Fjäriln vingad syns på Haga / sung by the operetta singer G. A. Lund, Stockholm] (in Swedish). Svensk mediedatabas. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ "Swedish Traditional Songs - Svenska visor - Nu blir sommar". Blue Music Group. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ "48° Zecchino d'Oro dal 22 al 26 Novembre 2005: Il Mio Cuore e' un Gran Pallone (Fjäriln)" (in Italian). Zecchino d'Oro. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ Scandinavian Songs and Ballads, trans. by Helen Asbury, Martin S. Allwood et al., (Mullsjö: Anglo-American Center, 1950).

- ^ Sweden Sings, trans. by Noel Wirén, (Stockholm: Nordiska Musikförlaget, 1955).

- ^ Fredman's epistles & songs, trans. by Paul Britten Austin, (Stockholm: Reuter & Reuter, 1977).

- ^ Summer in Sweden (Stockholm: Sveriges Radio, c. 1962).

- ^ To Carl Michael With Love (Stockholm: HMV, 1975).

- ^ Songs of Carl Michael Bellman (Monmouth, Great Britain: Nimbus Records, 1983).

- ^ Listen to Carl Michael Bellman! (Stockholm: Proprius, 1999).

- ^ Fredman's epistles and songs (Stockholm: Proprius, 2002).

Sources

- Bellman, Carl Michael (1790). Fredmans epistlar. Stockholm: By Royal Privilege.

- Britten Austin, Paul (1967). The Life and Songs of Carl Michael Bellman: Genius of the Swedish Rococo. New York: Allhem, Malmö American-Scandinavian Foundation. ISBN 978-3-932759-00-0.

- Britten Austin, Paul (1977). Fredman's Epistles and Songs. Stockholm: Reuter and Reuter. OCLC 5059758.

- Burman, Carina (2019). Bellman. Biografin [Bellman: The Biography] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag. ISBN 978-9100141790.

- Chapman, Henry Grafton (trans.) (1904). Hägg, Gustaf (ed.). Songs of Sweden: Eighty-Seven Swedish Folk- and Popular Songs. New York: G. Schirmer.

- Hassler, Göran; Dahl, Peter (illus) (1989). Bellman – en antologi [Bellman – an anthology]. En bok för alla. ISBN 91-7448-742-6.

- Kleveland, Åse (1984). Fredmans epistlar & sånger [The songs and epistles of Fredman]. Illustrated by Svenolov Ehrén. Stockholm: Informationsförlaget. ISBN 91-7736-059-1. (with facsimiles of sheet music from first editions in 1790, 1791)

- Lönnroth, Lars (2005). Ljuva karneval! : om Carl Michael Bellmans diktning [Lovely Carnival! : about Carl Michael Bellman's Verse]. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag. ISBN 978-91-0-057245-7. OCLC 61881374.

- Massengale, James Rhea (1979). The Musical-Poetic Method of Carl Michael Bellman. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International. ISBN 91-554-0849-4.

- Van Loon, Hendrik Willem; Castagnetta, Grace (1939). The Last of the Troubadours. New York: Simon & Schuster. OCLC 635648481.

External links

- "Fjäril'n vingad syns på Haga" facsimile at Litteraturbanken

- Text on Swedish WikiSource

- English version by Charles Wharton Stork, 1917

- Oscar Lundberg recording, 1917 (track 2)

- Live 2020 studio recording of 'Bellman 2.0' theatre concert (song starts at 45:00) at Västmanlands Teater by Nikolaj Cederholm and Kåre Bjerkø with their band