Frontispiece (architecture)

In architecture, the term frontispiece is used to describe the principal face of the building, usually referring to a combination of elements that frame and decorate the main or front entrance of a building.[1] The earliest and most notable variation of frontispieces can be seen in Ancient Greek Architecture[2] which features a large triangular gable, known as a pediment, usually supported by a collection of columns. However, some architectural authors have often used the term "frontispiece" and "pediment" interchangeably in reference to both large frontispieces decorating the main entrances, as well as smaller frontispieces framing windows which is traditionally known as a pediment.[3]

Frontispieces in pre-20th century architecture were considered decorative and ornamental structures used predominantly to dignify the façades of the building rather than for any structural or practical purpose.[4] With the proliferation of minimalistic ideas in 21st century architecture, a large emphasis is placed on simplicity and practicality when designing the façades of buildings.[5] Traditional decorative frontispieces are rarely used in the designing of post-modern buildings.

Frontispieces from different eras can be distinguished by the different variations of pediments used (triangular, segmented, open or broken pediments),[6] as well as the ornamentation of the columns corresponding to a particular architectural era.

Etymology

The word frontispiece describes the "decorated entrance of a building" and is historically derived from the Medieval Latin word frontispicium meaning the façade or exterior of the building.[7]

The word frontispicium stems from the latin frons meaning ‘forehead or front’ and specere meaning ‘to look at'. As a whole, the word took on the meaning: ‘a view of the forehead, judgement of character through facial features’.[8] Incorporated into the architectural sphere, it signifies the physical characteristics of the exterior of a building, especially pertaining to the architectural ornaments surrounding the entrance.[8]

Traditionally according to The Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences,[1] frontispieces should be used in reference to ornaments and structures specifically on the principle face of the building, while pediments should be used to describe smaller ornamentation above gates, windows, doors, etc.[1] especially ones with 'a triangular space that forms the gable of a low-pitched roof and that is usually filled with relief sculpture in classical architecture'.[9]

In modern day architecture, the frontispiece of a building is often referred to as the "façade" of the building.[10] Some architectural authors have also interchangeably used "frontispiece" with the word "pediment" in recent years given the similar nature of the ornaments involved.[3]

Frontispieces in literature

From the 17th century, the word "frontispiece" became synonymous to the small illustrations facing the title page of a book or the ornaments on the title page itself. Illustrations creating the frontispiece of a book would often borrow stylistic elements from architecture such as drawings of columns and architectural ornaments.[12] Following this development, authors began using the frontispieces of books, usually one of the only illustrations in the books during that period, to imply and communicate their perspectives and intentions as it was seen as the reader’s first gateway and glimpse into the book[12]— namely to put their literary stamp in their book as artists did with their works of art during that period.[13]

Function and elements

During the classical era between the 8th century BC and 6th century AD, frontispieces often consisted of a triangular gable, more specifically called the pediment of the building, which sat atop columns. Elaborate frontispieces were often only present on the façades of sacred buildings such as temples and tombs. Especially seen in ancient Greece and Rome, frontispieces were often used to depict mythological gods or even important figures in society depending on the purpose and patrons of the building.[14]

In the 21st century, frontispieces were more commonly used in reference to small frontispieces above windows and doors serving the pure purpose of ornamentation. The smaller frontispieces of this period often feature engaged columns, which are partly embedded in the wall of the façade.[2]

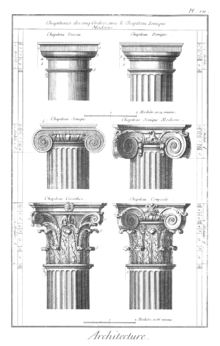

Columns

The style of the columns, often known as the architectural orders, found bracketing the entrance of buildings, is often used as one of the distinguishing features between frontispieces of different architectural periods.[15]

Pediments

Another distinguishing feature of frontispieces is the style of pediments used which can range from triangular pediments, segmental pediments, open pediments to broken pediments.[6]

Triangular pediments, often the most commonly used style of pediment features a triangle framed by a cornice or ledge, with the apex at the top, two symmetrical straight lines sloping to the ends of the horizontal cornice.[6] Segmental pediments, also called round or curved pediments have a rounded cornice replacing two sides of the traditional triangular pediment.[6] Open pediments can be distinguished by the absent or nearly absent strong horizontal line (cornice) of the pediment.[6] Broken pediments, made prominent in Baroque Architecture, can be identified by their non-continuous triangular outline, usually open at the top apex.[6] One of the prominent variations of a broken pediment is a swan-necked or ram's head pediment which has a highly ornamented S-shape.[6]

Triangular Pediment |

Segmental (curved) Pediment |

Open Pediment |

Broken Pediment |

Development and history of frontispieces

Classical architecture [8th century BC – 6th century AD]

In its classical form, the frontispiece of a building is commonly used to describe the ‘gable surmounting the façade of an ancient temple in classical architecture’ which is now often known as a pediment[16] and used as ornaments to the entrance of a building. During this era, frontispieces were used to describe ornaments on the principle face of the building and were predominantly used above large columns in the entrance, making up a large part of the façade of the building.

In Greek architecture, frontispieces can refer to both large ornamentation on the triangular tops of buildings as well as smaller frontispieces. Larger frontispieces found on the front façades of sacred buildings often depicted mythological gods or important figures in history depending on the purpose, and patronage, of the building.[14] The Parthenon, built in Ancient Athens, is one of the most recognisable examples of a classically designed frontispiece.[17] Built in 447BC, the ionic pediments of the Parthenon primarily featured Greek mythology and lore surrounding the Greek goddess, Athena, who was the patron of the Ancient city of Athens and the Parthenon.[18]

Classical elements such as superimposed orders, which refers to the architectural system of using different styles of columns for each storey of a building, was introduced and often used for decorative functions in classical architecture.[4] One of the most popular examples of superimposed orders was on the classical façade of the Colosseum.[19] Built in 70AD, the Colosseum featured an arrangement of orders on a classical frontispiece of several storeys, set one above the other with each storey corresponding to a particular architectural order.[20]

Romanesque architecture [6th–11th century AD]

The move from the typical triangular pediments to segmental, curved pediments is seen in the carvings on the imperial sarcophagi in Rome which depicts the architecture of the era.[21] Romanesque architecture also popularised the use of smaller, ornamental frontispieces surrounding windows. Many well-preserved examples of Roman influenced frontispieces can be found in Provence, France due to the use of ‘fine quality building stone’ while others constructed with a decorative veneer were quickly lost.[12]

Romanesque influences in frontispieces can also be seen in the aerarium, treasury of ancient Rome, which features classical Roman architecture with both traditional triangular pediments as well as elaborate broken pediments.[22]

The Tombs of Lorenzo and Giulano de’Medici sculpted by Michelangelo also features etchings of frontispiece styles popular during this era which include the use of smaller, decorative frontispieces with curved pediments.

Renaissance architecture [early 14th – 16th century AD]

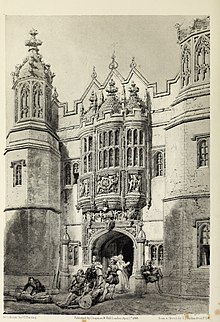

Renaissance Architecture, which ushered a revival of ancient Greek and Roman classical architectural forms,[6] saw the introduction and proliferation of classical elements, which included the frequent usage of large columns and pediments.[4] Classical elements, such as superimposed orders, were reintroduced in the sixteenth century to dignify the entrances to some important houses and some collegiate buildings.[4]

In the late 1520s to early 1530s, there was a revival of the heavy use of dense classical ornaments on the frontispieces which can be seen on the facade of Hengrave Hall, Suffolk, England built in 1538,[4] as well as the addition of elements distinctive of the Italian Renaissance such as the use of terracotta moulded decorative elements[23] featured on the façade of the hall entrance to Richard Weston’s Sutton Place, Surrey, built in 1533.

|

|

In the mid-16th century, the building of Old Somerset House was considered one of "the first deliberate attempts to build, in England, a front composed altogether in the classical taste"[24] and was "unquestionably one of the most influential buildings of the English Renaissance."[24] Although there was nothing new about the principle features of the façade, the stylistic attempts at consistency and symmetry in the structure of the frontispiece showed the growing awareness, during the late renaissance era in England,[4] for 'regularity in planning and greater visual unity and symmetry' and a 'consistent use of the classical orders'.[25] The three-storey frontispiece prominently placed at the centre of the façade of the Old Somerset House comprised a gateway in the form of a triumphal arch with superimposed orders and columns flanking windows the structure of which can be traced back to the arch in Castel Nuovo, Naples, borrowing the triumphal arch motif from Roman antiquity.

In contrast to the predominantly decorative functions of frontispieces in the Classical Era, the sixteenth century also brought the introduction of the first classical portico to England[4] at St Paul's Cathedral, which was design by Inigo Jones. The portico served the more practical and structural purpose of providing a covered walkway at the entrance of the building.[26]

It was noted by Richard John Riddell, who analysed entrance-porticos in English Renaissance architecture, that the most impressive and architecturally sophisticated frontispieces were often set against houses 'by men who enjoyed or aspired to preferment and high office, with the immense political power and social prestige, and by academics who wished to give permanent expression to the distinction of their college and university'.[4] Frontispieces of this nature were purely for applied and decorative functions, even the 'fullest extent of the role of the columns in their load-bearing capacity was to hold up each other and not the building'.[4]

Baroque architecture [17th – mid 18th century AD]

In baroque architecture, frontispieces also took on semi-oval structures which decorated the tops of the entrances with added embellishments synonymous to the household or building. Frontispieces during this period featured more opulent and theatric style in ornamentation and grandeur as was common during the era. During this period, the use of broken frontispieces and heavy ornaments was featured in many of the buildings.[27] This is seen in Palácio do Freixo designed by Nicolò Nasoni , who was heavily influenced by the baroque architecture. Another known example of this is seen in Andrea Palladio’s Church of San Giorgio Maggiore, in Venice which features an unusual broken pediment as it is the result of superimposing two temple fronts.[22]

Neoclassical architecture [mid-18th – early 19th century AD]

In the late 18th century to the 19th century, neoclassical frontispieces were often described as ‘a portion of the façade of a building, that is slightly raised from the rest of the building’ using engaged columns with lighter ornamentation.[12] Frontispieces during the neoclassical era commonly consisted of simple geometric shapes with a large emphasis on the use of columns, especially Doric columns.

Post-modernism architecture [late 20th – 21st century AD]

In the 20th century post-modernism era, buildings such as the Marco Polo House designed by Ian Pollard and the 550 Madison Avenue building designed by Philip Johnson feature large scale broken pediments at the top of their buildings providing a post-modern take on broken pediments often found in baroque architecture.[22]

Though some architects have designed buildings modernising on architectural styles and structures of the past, architecture of the 21st century seems to be moving in the direction of minimalism, contrary to grandiose nature of frontispieces seen from the Classical Era to the Neoclassical Era. Minimalism in architecture is often characterised by the rejection of ornament and the ‘emphasis on rational use and function’[29] and popularised in the late 1980s in London and New York with buildings combining clean lines and architectural profiles usually tied to iconic geometry.[29]

These moves towards minimalism can be seen in the proliferation of the Wabi-sabi aesthetics, popularised in Japan which translates roughly to ‘the elegant beauty of humble simplicity’,[28] encapsulating Taoist and Buddhist ideologies of accepting nature and ‘favouring the imperfect and incomplete in everything’.[28] The Scandinavian notion of Hygge has similar roots in minimalism. Hygge designs and aesthetics are inspired by the Scandinavian landscape of fjords, forests and mountains and are characterised by mild colour palettes consisting of pewter grays, soft pastel shades with flashes of bright metallic shades.[30]

References

- ^ a b c Croker, Temple Henry (12 April 2012). The Complete Dictionary Of Arts And Sciences, Volume 2. Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1248506073.

- ^ a b Lancaster, Clay (March 1950). "Adaptations from Greek Revival Builders' Guides in Kentucky". The Art Bulletin. 32 (1): 62–70. doi:10.2307/3047271. JSTOR 3047271.

- ^ a b "Frontispiece Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Riddell, Richard John (25 May 2022). The Entrance-Portico in the architecture of Great Britain, 1630-1850 (Thesis). University of Oxford.

- ^ "Ornamentation in Contemporary Architecture - Rethinking The Future". RTF | Rethinking The Future. 2020-05-06. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Craven, Jackie (13 April 2019). "A Pediment can Make Your Home a Greek Temple". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ "Meaning of Frontispieces". Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ a b "frontispiece (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ "Definition of PEDIMENT". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ "frontispiece". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ "print; frontispiece British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ a b c d Conroy, Derval (18 July 2013). "In the Beginning was the Image: Feminist Iconography and the Frontispiece in the 1640s". Seventeenth-Century French Studies. 23: 27–42. doi:10.1179/c17.2001.23.1.27. S2CID 218646099.

- ^ Fiore, Julia. "8 famous artists who kid their self-portraits in their paintings". CNN Style. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ a b Dowden, Ken (10 September 1992). The Uses of Greek Mythology. Routledge. ISBN 9780203138571.

- ^ Holland, Leicester Bodine (March 1921). "Transformations of the Classic Pediment in Romanesque Architecture". American Journal of Archaeology. 25 (1): 55–74. doi:10.2307/497889. JSTOR 497889. S2CID 193074607.

- ^ "Pediment". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ Scott, Gregory J. "Design Intervention: The long and noble history of pediments". LancasterOnline. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ "Athena Parthenos by Phidias". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- ^ Chitham, Robert (12 May 2014). The classical orders of architecture. London. ISBN 978-1-4832-7823-0. OCLC 892067621.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Curl, James Stevens (2006), "assemblage of Orders", A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780198606789.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9, retrieved 2022-05-25

- ^ Holland, Leicester Bodine (March 1921). "Transformations of the Classic Pediment in Romanesque Architecture". American Journal of Archaeology. 25 (1): 55–74. doi:10.2307/497889. JSTOR 497889. S2CID 193074607.

- ^ a b c Furman, Adam Nathaniel. "Seven Broken Pediments". The RIBA Journal. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Della Robbia: Sculpting with Color in Renaissance Florence". www.nga.gov. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ a b Summerson, John (1935). John Nash, Architect to King George IV. G. Allen & Unwin Limited, 1935. pp. 45–46.

- ^ Howard, Maurice (1987). The early Tudor country house : architecture and politics, 1490-1550. London: G. Philip. ISBN 0-540-01119-3. OCLC 20352890.

- ^ "Portico - History of Early American Landscape Design". heald.nga.gov. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ Bury, J.B. (1 October 1956). "Late Baroque and Rococo in North Portugal". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 15 (3): 7–15. doi:10.2307/987760. JSTOR 987760.

- ^ a b c Crossley-Baxter, Lily. "Japan's unusual way to view the world". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ a b "Minimalist Modern: The Architecture of Rural Retreats". ArchDaily. 2022-03-05. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ "What Does Hygge Really Mean?". Architectural Digest. 2017-02-07. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

External links

Media related to Frontispieces (architecture) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Frontispieces (architecture) at Wikimedia Commons