Plantation economy

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (December 2010) |

| Part of a series on |

| Economic systems |

|---|

|

Major types

|

A plantation economy is an economy based on agricultural mass production, usually of a few commodity crops, grown on large farms worked by laborers or slaves. The properties are called plantations. Plantation economies rely on the export of cash crops as a source of income. Prominent crops included cotton, rubber, sugar cane, tobacco, figs, rice, kapok, sisal, and species in the genus Indigofera, used to produce indigo dye.

The longer a crop's harvest period, the more efficient plantations become. Economies of scale are also achieved when the distance to market is long. Plantation crops usually need processing immediately after harvesting. Sugarcane, tea, sisal, and palm oil are most suited to plantations, while coconuts, rubber, and cotton are suitable to a lesser extent.[1]

Conditions for formation

Plantation economies are factory-like, industrialised and centralised forms of agriculture,[citation needed] owned by large corporations or affluent owners. Under normal circumstances, plantation economies are not as efficient as small farm holdings, since there is immense difficulty in proper supervision of labour over a large land area.[citation needed] When there are large distances between the plantations and their markets, processing can reduce the bulk of the crop and lower shipping costs.

Large plantations produce large quantities of a good are able to achieve economies of scale for expensive processing machinery, as the per unit cost of processing is greatly diminished. This economy of scale can be achieved best with tropical crops that are harvested continuously through the year, fully utilising the processing machinery. Examples of crops that are suitable to be processed are sugar, sisal, palm oil, and tea.[2]

North American plantations

In the Thirteen Colonies, plantations were concentrated in the South. These colonies included Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. They had good soil and long growing seasons, ideal for crops such as rice and tobacco. The existence of many waterways in the region made transportation easier. Each colony specialized in one or two crops, with Virginia standing out in tobacco production.[3]

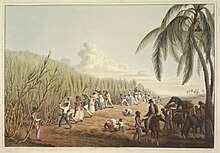

Slavery

Planters embraced the use of slaves mainly because indentured labor became expensive. Some indentured servants were also leaving to start their own farms as land was widely available. Colonists tried to use Native Americans for labor, but they were susceptible to European diseases and died in large numbers. The plantation owners then turned to enslaved Africans for labor. In 1665, there were fewer than 500 Africans in Virginia but by 1750, 85 percent of the 235,000 slaves lived in the Southern colonies, Virginia included. Africans made up 40 percent of the South’s population.[3]

According to the 1840 United States Census, one out of every four families in Virginia owned slaves. There were over 100 plantation owners who owned over 100 slaves.[4] The number of slaves in the 15 States was just shy of 4 million in a total population 12.4 million and the percentage was 32% of the population.

- Number of slaves in the Lower South: 2,312,352 (47% of total population) 4,919 million.

- Number of slaves in the Upper South: 1,208,758 (29% of total population) 4,165 million.

- Number of slaves in the Border States: 432,586 (13% of total population) 3,323 million.

Fewer than one-third of Southern families owned slaves at the peak of slavery prior to the Civil War. In Mississippi and South Carolina the figure approached one half. The total number of slave owners was 385,000 (including, in Louisiana, some free African Americans), amounting to approximately 3.8% of the Southern and Border states population.

On a plantation with more than 100 slaves, the capital value of the slaves was greater than the capital value of the land and farming implements. The first plantations occurred in the Caribbean islands, particularly, in the West Indies on the island of Hispaniola, where it was initiated by the Spaniards in the early 16th century. The plantation system was based on slave labor and it was marked by inhumane methods of exploitation. After being established in the Caribbean islands, the plantation system spread during the 16th,17th and 18th century to Mexico, Brazil, Britain’s southern Atlantic colonies in North America and Indonesia. All the plantation system had a form of slavery in its establishment, slaves were initially forced to be labors to the plantation system, these slaves were primarily native Indians, but the system was later extended to include slaves shipped from Africa. Indeed, the progress of the plantation system was accompanied by the rapid growth of the slave trade. The plantation system peaked in the first half of the 18th century, but later on, during the middle of 19th century, there was a significant increase in demand for cotton from European countries, which means there was a need for expanding the plantation in the southern parts of United States. This made the plantation system reach a profound crisis, until it was changed from being forcing slave labour to being mainly low-paid wage labors who contained a smaller proportion of forced labour. The monopolies were insured high profits from the sale of plantation products by having cheap labours, forced recruitment, peonage and debt servitude.[5]

Atlantic slave trade

Enslaved Africans were transported from Africa by European slave traders to Europe's colonies in the Western Hemisphere. They were shipped from ports in West Africa to the New World. The journey from Africa across the Atlantic Ocean was called "the middle passage", and was one of the three legs which comprised the triangular trade among the continents of Europe, the Americas, and Africa.

By some estimates, it is said that some ten million Africans were brought to the Americas. Only about 6% ended up in the North American colonies, while the majority were taken to the Caribbean colonies and South America. A reason many did not make it to the colonies at all was disease and illness. Underneath the slave ship's decks, Africans were held chest-to-chest and could not do much moving. There was waste and urine throughout the hold; this caused the captives to get sick and to die from illnesses that could not be cured.[6]

As the plantation economy expanded, the slave trade grew to meet the growing demand for labor.[7]

Industrial Revolution in Europe

Western Europe was the final destination for the plantation produce. At this time, Europe was starting to industrialize, and it needed a lot of materials to manufacture goods. Being the power center of the world at the time, they exploited the New World and Africa to industrialize. Africa supplied slaves for the plantations; the New World produced raw material for industries in Europe. Manufactured goods, of higher value, were then sold both to Africa and the New World. The system was largely run by European merchants.[8]

Sugar plantations

Sugar has a long history as a plantation crop. Cultivation of sugar had to follow a precise scientific system to profit from the production. Sugar plantations everywhere were disproportionate consumers of labor, often enslaved, because of the high mortality of the plantation laborers. In Brazil, plantations were called casas grandes and suffered from similar issues.

The slaves working the sugar plantation were caught in an unceasing rhythm of arduous labor year after year. Sugarcane is harvested about 18 months after planting and the plantations usually divided their land for efficiency. One plot was lying fallow, one plot was growing cane, and the final plot was being harvested. During the December–May rainy season, slaves planted, fertilized with animal dung, and weeded. From January to June, they harvested the cane by chopping the plants off close to the ground, stripping the leaves and then cutting them into shorter strips to be bundled off to be sent to the sugar cane mill.

In the mill, the cane was crushed using a three-roller mill. The juice from the crushing of the cane was then boiled or clarified until it crystallized into sugar. Some plantations also went a step further and distilled the molasses, the liquid left after the sugar is boiled or clarified, to make rum. The sugar was then shipped back to Europe. For the slave laborer, the routine started all over again.

With the 19th-century abolition of slavery, plantations continued to grow sugar cane, but sugar beets, which can be grown in temperate climates, increased their share of the sugar market.

Indigo plantations

Indigofera was a major crop cultivated during the 18th century, in Venezuela, Guatemala—and Haiti until the slave rebellion against France that left them embargoed by Europe and India in the 19th and 20th centuries. The indigo crop was grown for making blue indigo dye in the pre-industrial age.

Mahatma Gandhi's investigation of indigo workers' claims of exploitation led to the passage of the Champaran Agrarian Bill in 1917 by the British colonial government.

Southeast Asia

In Southeast Asia British and Dutch colonies established plantations to produce agricultural commodity products including tea, pepper and other spices, palm oil, coffee, and rubber. Large scale agricultural production continues in many areas.[9]

Currencies

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2017) |

The currency for the Georgia colony was the pound sterling, a gold coin or very light green bill with the national pound symbol. The currency is worth about one and one half U.S. dollar.

The currency for the New York was at the time of the colony the New York pound. This currency was primarily used and made in the 1700s.

See also

- Banana republic

- History of commercial tobacco in the United States

- History of sugar

- King Cotton

- Latifundium

- Sugar plantations in the Caribbean

- Tropical agriculture

References

- ^ Jeffery Paige, Agrarian Revolution, 1975.

- ^ Jeffrey M. Paige (1978). Agrarian Revolution. Simon and Schuster. pp. 14–15. ISBN 0029235502.

- ^ a b The Southern Colonies: Plantations and Slavery, by Kalpesh Khanna Kapurtalawla

- ^ "PBS The Slaves' Story". PBS. Retrieved 2006-03-24.

- ^ Plantation System. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Plantation System

- ^ Stephen Behrendt (1999). "Transatlantic Slave Trade". Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience

- ^ "How Slavery Helped Build a World Economy". National Geographic News. 2003-01-03. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- ^ The Abolition Project, http://abolition.e2bn.org/slavery_42.html, accessed 3-26-2013

- ^ Bosma, Ulbe (30 July 2019). The Making of a Periphery: How Island Southeast Asia Became a Mass Exporter of Labor. ISBN 9780231547901.