Indiana Mammoth Internal Improvement Act

| Mammoth Internal Improvement Act | |

|---|---|

A map showing the extent of the projects along with the portions that were not completed by the state | |

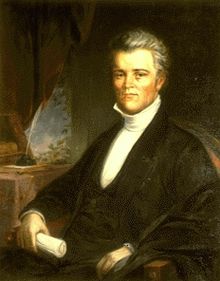

| Governor Noah Noble | |

| Enacted by | Governor Noah Noble |

| Signed | 1836 |

The Indiana Mammoth Internal Improvement Act was a law passed by the Indiana General Assembly and signed by Whig Governor Noah Noble in 1836 that greatly expanded the state's program of internal improvements. It added $10 million to spending and funded several projects, including turnpikes, canals, and later, railroads. The following year the state economy was adversely affected by the Panic of 1837 and the overall project ended in a near total disaster for the state, which narrowly avoided total bankruptcy from the debt.

By 1841, the government could no longer make the interest payments, and all the projects, except the largest canal, were handed over to the state's London creditors in exchange for a 50% reduction in debt. Again in 1846, the last project was handed over for another 50% reduction in the debt. Of the eight projects in the measure, none were completed by the state and only two were finished by the creditors who took them over.

The act is considered one of the greatest debacles in the history of Indiana. Public blame was placed on the Whig party who had been in control of the General Assembly and the governorship during the passage of the act and the subsequent bankruptcy, though only nine members of both houses voted against the bill. After the scope of the financial disaster became apparent to the state, the Whig party gradually began to collapse in Indiana, leading to a period of Democratic control of the General Assembly that lasted until the middle of the American Civil War.

Despite the dire immediate effects on the state's finances, the project ultimately fed a 400% increase in state land values, and provided numerous other direct and indirect benefits to Indiana. The Wabash and Erie Canal, which was partially funded by the act, became the longest canal in North America and remained in operation until rendered obsolete by the railroads in the 1880s.

Background

[edit]When the state of Indiana was formed in 1816, it was still a virtual wilderness, and settlement was limited to the southern periphery where easy access to the Ohio River provided a convenient means to export produce. The only significant road in the region was the Buffalo Trace, an old, dirt bison trail that crossed the southern part of the state. After statehood several plans had been made to improve the transportation situation, like the creation of small local roads, the larger Michigan Road, and a failed attempted by the Indiana Canal Company to build a canal around the Falls of the Ohio.[1][2] The national economy entered a recession following the Panic of 1819, and the state's only two banks collapsed in the immediate years that followed, ending the state's early improvement programs without having achieved much success and leaving the state with a modest debt.[3]

The 1820s were spent repairing the state's finances and paying down the debt. A request was sent to Congress asking for the federal government to assist the young state in improving the transportation situation. Canals were at that time being constructed in several of the eastern states and New York and Pennsylvania hoped to link to the Mississippi River System by building canals through Indiana. With their support, on May 26, 1824, Congress granted Indiana a stretch of land 320 feet (98 m) wide on any route a commission would map out, but the state had to promise to begin construction of a canal on the land within twelve years.[4]

Many in the Indiana General Assembly considered the grant insufficient, and requested the grant be expanded to a one-mile (1.6 km) wide strip, but Congress did not act. Most of the population at the time lived along the Ohio River, and the canal would be little benefit to them, but they would bear the burden of paying for it, so their representatives opposed the idea altogether. They successfully barred the creation of a canal.[5][6]

On March 2, 1827, Congress made a new offer to the state, granting a half mile wide strip and to assist in the funding of construction. This time the General Assembly accepted the offer, passing legislation on January 5, 1828, to create a canal commission to lay out the path of the canal, but no state funding was approved. The commission laid out a short six-mile (9.7 km) canal that would become the starting point of the Wabash and Erie Canal. Funding immediately became an issue in the legislature where the lowest cost estimate was $991,000.[7]

Again the southern part of the state objected, instead favoring a canal in the Whitewater Valley, then the most populated part of the state. Governor James B. Ray objected to canals as a total waste of money, and insisted on the creation of railroads instead; he threatened a veto of any canal project.[7] Because the state refused to help fund the project, it had to rely on the federal funds and the income the commission collected from selling lands adjacent to the proposed canal route. Slowly enough funds were collected and construction began on the route in 1831.[8][9]

In 1829 the National Road entered Indiana. Funded by the federal government, the project laid a large highway across the central part of the state. By 1834 the opposition to the canal had disappeared and the project was being constructed at little cost to the state and was proving to be profitable, so the General Assembly granted funds to the project to connect it to Lafayette. To fund the project, and in response to the closure of the Second Bank of the United States, the state established the Bank of Indiana. Bonds were issued through the bank who then sold them to creditors in London to fund the early stages of the project, but it soon became apparent that it would take far more funds than could be obtained by the bank bonds alone.[10]

Passage of the law

[edit]

In 1836, legislation was created by the Indiana General Assembly to dramatically expand the scope of the internal improvements. At first, members only intended to continue funding the Wabash and Erie, but many representatives opposed the spending because it would have little benefit for their own constituents as the canal bypassed most of the major settlements in the state. As a compromise, additional projects were agreed on so that all the cities in the state would be connected by either canal, railroad, or turnpike. To appease the majority of the population that lived along the Ohio River, the bill called for the Vincennes Trace to be paved, making it usable year round.[11]

A Lafayette Turnpike was also approved, and to gain support of the representatives from the population centers in the far northern part of the state, the Michigan Road was also paved. To appease the railroad faction, two lines were approved connecting Lawrenceburg to Indianapolis, and Madison to Lafayette. The Whitewater Valley was the most populous part of the state, and to win over their representatives, funding was added for a canal to be built in their valley. To also get support from the central part of the state, and to connect Indianapolis to the new canals, a Central Canal was also funded.[11]

Over $2 million had already been borrowed, and the new bill proposed borrowing another $10 million. This was added to the $3 million already procured through land sales. Seeing the success of canals in the eastern United States, it was believed that the projects would be very profitable for the state and that their revenue would quickly pay back the loans, and provide the funds to complete the projects. The state's regular revenue, primarily from property taxes, were at that time less than $65,000 annually, and the amount of the debt was greater than the tax receipts of the entire history of the state.[12] The sum borrowed was equal to one-sixth of all the wealth in the state. Despite the scale of the project, the representatives from the counties on the Ohio River still largely opposed the project.[11]

For canals, the project called for the creation of a canal from Indianapolis to Ohio River at Evansville, called the Indiana Central Canal. Funding was included for another canal to connect the Wabash River in Peru to the Ohio River in Lawrenceburg known as the Whitewater Canal. Additional funding was granted to the Wabash and Erie Canal for expansion to Terre Haute. The canals received the majority of the funds from the bill, because it was believed that the canals could be constructed from local materials which would help boost the local economy.[12][13] A later investigation showed that parts of the state were entirely unsuited for the canals, and the project were doomed from the start. However, the state had not conducted surveys of the land before passing the bill to ensure their suitability.

The bill also funded, but to a much lesser degree, a railroad connecting Madison to Indianapolis, another railroad from Shelbyville to Indianapolis, the paving of the Buffalo Trace and renaming it the Vincennes Trace, and the paving of the remainder of the Michigan Road. Most of the money from the project was gathered by mortgaging nine million acres (36,000 km2) of state owned land through agents of the Bank of Indiana to creditors in London and New York.[12]

Governor Noah Noble was a major supporter of the bill and it passed by the overwhelmingly Whig controlled General Assembly, although it was opposed by several prominent legislators including Dennis Pennington, James Whitcomb, Calvin Fletcher and John Durmont. Pennington believed the canals were a waste of money and would soon be made obsolete by the railroads.[14] Whitcomb outright rejected the idea of spending such a large sum of money, saying it would be impossible to pay back. The bill's passage met with statewide celebrations. Citizens saw it as a critical modernization of the state. Governor Noble considered the act his crowning achievement. Noble was concerned however that the assembly had not passed the 50% tax increase he had told them was necessary to take care of the debt the state was expecting to take.[15]

The bill created a Board of Improvement and a Board of Funds Commissioners to oversee the projects. Two thirds of the funds were spent on the canals, with the Central Canal getting the most money.[16] Jesse L. Williams was named chief engineer.[17]

Enactment

[edit]

From the early onset it was noted that the different projects did not work together, but instead competed with each other for funds and land. By trying to construct all the project at once, there was also a labor shortage and the projects began competing with each other for workers, significantly raising the originally projected labor costs. This posed a problem for the government, because they did not provide enough funds to complete each of the projects at the rates being paid, instead expecting them to start making money on their own, and funding their own completion.[16] There was a brief by Governor David Wallace to attempt to force the commission to only build one route at a time to conserve funds and avoid what was becoming seen as an impending financial disaster, but the different factions in the General Assembly could not agree on which line should be completed first.[18]

The Wabash and Erie Canal was the most successful of the canal projects, and was profitable early on, but never to the extent expected. The Central Canal was a major failure, with only a few miles of canal dug near Indianapolis before the project was out of money. The Whitewater Canal was proceeding along well until its earthen walls and feeder dams were the victims of muskrats who burrowed through the walls, causing hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages for which there was no money to repair.[19] At the height of the operation, over ten thousand workers were employed on the canal projects.[17]

The rail line from Madison to Indianapolis was built much more cheaply than the canals; $1.3 million was appropriated. It was however, considerably over budget due to the increased costs of having to build a grade out of the low lying Ohio Valley onto the Indiana table land, so the project could not be finished. Had the project instead started in Indianapolis, it would have been able to earn income on freight and passengers along the relatively flat central Indiana portion, and been able to fund itself to construct the grade into Madison. The Vincennes Trace was paved from New Albany to Paoli at a cost of $1,150,000, with another 75 miles (121 km) still requiring pavement when the project ran out of money.

The Panic of 1837, caused primarily by western land speculation, left the state in dire straits financially. Income shrank, and in 1838 the state's taxation revenue was $45,000, but the interest on the state's growing debt was $193,350. Governor Wallace made the startling report to the General Assembly who began to wrangle over what action should be taken. Provisions were made to make debt payments with more borrowed money, in the hope that the projects could be finished before the state's credit was maxed out.[20]

The gamble proved to be a bad decision and by 1839 there was no money left for the projects and work was halted. Work only continued on the Wabash and Erie where workers were paid with stock in the canal, and not cash, and supplies were purchased using the federal funding. At that time 140 miles (230 km) of canal had been built for $8 million, and $1.5 million spent on 70 miles (110 km) of railroad and turnpike. The state was left with a $15 million debt, and only a trickle of tax revenue.[20]

In hope to increase revenues, the state reformed property tax assessment to be based on property values, as opposed to a set amount per acre. The modest reform boosted revenues by 25% in the following year, but was still nowhere near enough to cover the gap. Governor Wallace announced to the General Assembly in his last year as governor that the state would be insolvent within a year. The 1841 budget had over $500,000 in debt payments, plus regular spending, but revenues that year were only $72,000. The state was unofficially bankrupt.[21] The proponents of the system had promised their constituents that taxes would not need to be increased, and that once the projects were finished taxes could perhaps be abolished because tolls would pay all the state's needs. Because of this, no provisions had been made to pay interest on the massive debt.[17]

In 1841 Governor Samuel Bigger proposed the creation of county boards to set property values. The result of the new system led to as much as a 400% tax increase in some parts of the state. Citizens decried the draconian tax hikes, and many refused to pay. The General Assembly was forced to repeal the system the following year.[17]

James Lanier, president of the Bank of Indiana, was sent by Governor Bigger to negotiate with the state's London creditors in a hope to avoid total bankruptcy in 1841. He negotiated the transfer of all of the projects, except the Wabash and Erie, to the creditors in exchange for a 50% reduction in the debt they held, lowering the total state debt to $9 million.[17]

Although the debt decrease lessened the strain on the state, the debt payment was still far more than the state could afford. On January 13, 1845, the General Assembly passed a resolution issuing an official apology to the state's creditors and the state and federal governments of the United States for the repudiation of large parts of their debt. The resolution stated "We regard the slightest breach of plighted faith, public or private, as an evidence of a want of that moral principle upon which all obligations depend: That when any state in this Union refuses to recognize her great seal as the sufficient evidence of her obligation she will have forfeit her station in the sisterhood of States, and will no longer be worthy of their respect and confidence." The governor was directed to forward copies of the apology to each of the states. The result of the repudiation ruined Indiana's credit for nearly twenty years.[22]

The Whigs suffered from the failure of the project and Democrat James Whitcomb, an opponent of the projects from the beginning, was elected governor. A Democratic majority had already came to power in the statehouse the year before. With their support he began negotiations to end the crisis. Charles Butler arrived from New York to negotiate on behalf of the state's creditors in 1846. The proposed deal was for the state to trade majority ownership of the Wabash and Erie for another 50% reduction in the debt, leaving the state owing $4.5 million and ending the financial crisis. Although the debt was significantly reduced, payment on it was still over half of the state budget, but the growing population of the state was quickly raising tax revenues.[23][24]

Aftermath

[edit]

The creditors had taken the public works expecting that they could be quickly completed and become profitable, but were disappointed to discover that not to be the case for all the projects. The Vincennes Trace was renamed the Paoli Pike, and operated for several years as a private toll road until repurchased by the state thirty years later. Its tolls covered its operating costs, but it was never profitable. The Central Canal was abandoned as a total loss, the expense to finish it was considered to be too great for any possible profitability, and the area was found to be unsuited for canals.[25]

The Whitewater Canal had about one fifth of the line completed, and although it was not finished, the existing portion remained in use until 1847 when a portion of the canal collapsed and rendered the northern section unusable. The southern section continued in use until 1865 when it was closed after losing traffic to a railroad built adjacent to the canal. The Wabash and Erie was finally completed in 1848 and continued to operate for thirty-two years, but the high-rise portions of the canal in the central part of the state were found to be high maintenance and the frequent victim of muskrats.[25]

The cost of upkeep, and competition from the railroad eventually led to the collapse of the canal and its company in the 1870.[25] The rail line from Madison to Indianapolis was also abandoned by the creditors and sold to a group entrepreneurs, who were able to raise funds to complete the line. The Madison & Indianapolis Railroad was instantly profitable and went on to expand and connect to several other cities.

In 2008, all that remains of the Wabash and Erie is a restored fifteen-mile (24 km) stretch and a few ponds. Much of the canal lands were sold to railroad companies and were excellent land for constructing rail lines. The turnpikes and railroads turned out to be the most successful projects, and some parts of them have remained in use until modern times.

Although the government lost millions, there were significant benefits for the areas of the state where the projects succeeded. On average, land value in the state rose 400%, and the cost of shipping goods for farmers was drastically decreased, and increasing the profit on their goods. The investors in the Bank of Indiana also made substantial profits, and the investments served as the start of a modern economy for the state.[26] The act is often considered the greatest legislative debacle in the history of the state.

See also

[edit]- Wabash and Erie Canal

- Whitewater Canal

- Indiana Central Canal

- Michigan Road

- National Road

- Vincennes Trace

General:

Notes

[edit]- ^ Dunn, p. 382–383, 386

- ^ Kleber, p. 203

- ^ ISL, pp. 144–158

- ^ Eseray p. 353

- ^ Eseray, 354

- ^ Dunn, p. 388

- ^ a b Eseray, p. 357

- ^ Eseray, p. 358

- ^ Shaw, p. 135

- ^ Dunn, pp. 390–392

- ^ a b c Eseray, p. 361–364

- ^ a b c Dunn, pp. 398–404

- ^ Shaw, p. 137

- ^ Dunn, p. 408

- ^ Woollen, p. 82

- ^ a b Shaw, p. 138

- ^ a b c d e Shaw, p. 139

- ^ Eseray, p. 367

- ^ Dunn, p. 399

- ^ a b Dunn, p. 426

- ^ Esarey, p. 359

- ^ Eseray, p. 379

- ^ Dunn, p. 415

- ^ Dunn, p. 427–428

- ^ a b c Dunn, p. 410

- ^ Dunn, p. 418

Sources

[edit]- Dunn, Jacob Piatt (1919). Indiana and Indianans. Vol. V.I. Chicago & New York: The American Historical Society.

- Eseray, Logan (1915). A History of Indiana. W.K. Stewart co.

- Indiana State Library, Indiana Historical Society (1909). Indiana Magazine of History. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- Kleber, John E (2001). Encyclopedia of Louisville. University Press of Kentucky.

- Shaw, Ronald E. (1993). Canals for the Nation. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-0815-2.

- Woollen, William Wesley (1975). Biographical and Historical Sketches of Early Indiana. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 0-405-06896-4.