Treaty on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea

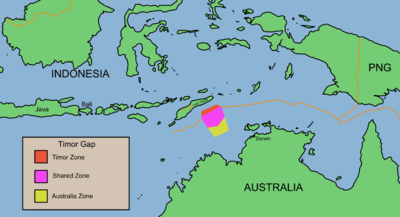

Officially called the Treaty between Australia and the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS),[1] the treaty provides for the equal distribution of revenue derived from the disputed Greater Sunrise oil and gas field between Australia and East Timor. The field is located in the Timor Gap where Australia and East Timor have overlapping claims over the continental shelf or seabed. Prior to the treaty, East Timor would only have received about 18% of the revenue from the field.

CMATS also puts on hold the right by both countries to claim sovereign rights, discuss maritime boundaries or engage in any legal process in relation to maritime boundaries or territorial jurisdiction for 50 years which is the duration the treaty is in effect. CMATS is one of three treaties concerning the exploitation of gas and petroleum in the Timor Gap and is to be "read together" with the other two treaties, namely the Timor Sea Treaty of 2002 and the Sunrise International Unitization Agreement (Sunrise UIA) of 2003.

CMATS was signed in Sydney on January 12, 2006, by Australian Foreign Affairs Minister Alexander Downer and his East Timorese counterpart José Ramos-Horta. It came into force on February 23, 2007, with the exchange of notes in Dili, East Timor. The East Timor parliament had ratified the treaty while Alexander Downer invoked the national interest exemption to fast-track ratification at the Australian Parliament.

The Treaty became the subject of an action by East Timor before the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague as a result of the Australia-East Timor spying scandal. Hearings commenced on 29 August 2016.[2]

In 2017, East Timor terminated CMATS, claiming it was invalid, due to Australian intelligence operations in 2004.[3] Following a resolution at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, CMATS was succeeded in 2018 by the Treaty Between Australia and the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste Establishing Their Maritime Boundaries in the Timor Sea.[4]

Treaty provisions

[edit]

Without prejudice to the final settlement of borders

[edit]CMATS will not prejudice or affect Timor-Leste's or Australia's legal position or legal rights to the delimitation of their respective maritime boundaries. It will also not amount to a renunciation of any right or claims.[5]

Treaty duration

[edit]The treaty replaces Article 22 of the Timor Sea Treaty, making its validity period the same as CMATS's, which is until 2057. The Timor Sea Treaty can however be renewed by the agreement of both parties.[6]

Moratorium

[edit]Both parties will not "assert, pursue or further by any means in relation to the other party" its claims to sovereign rights, jurisdiction and maritime boundaries for the period CMATS is in force.[7] Both countries will also not start any proceedings against the other before any court on issues related to maritime boundaries or delimitation in the Timor Sea.[8] Furthermore, no court proceedings involving the countries shall decide or comment on anything related to maritime boundaries or delimitation and any such comment or finding shall be of no effect and shall not be relied upon at any time.[9] Neither country shall also pursue in any international organization matters related to maritime boundaries or delimitation.[10]

This "postponement" on settling the question of sovereignty over the seabed is aimed at providing stability for the legal regime governing the exploitation of the Greater Sunrise field[11] and removing the "petroleum factor" once the two countries get down to settling their maritime boundaries.[12]

Existing petroleum exploitation to continue

[edit]Under CMATS, both countries can continue with petroleum exploitation activities in areas in which had been authorised by its domestic legislation on 19 May 2002.[13] This is taken to allow Australia to continue with petroleum exploration and exploitation activities in the Laminaria-Coralina and other fields it claims to be located in its territorial waters as a result of the Agreement between the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia and the Government of the Republic of Indonesia Establishing Certain Seabed Boundaries in the Area of the Timor and Arafura Seas, Supplementary to the Agreement of 18 May 1971 (See Australia-Indonesia border page). East Timor had not granted any such activity as it had not attained independence at the said date. The state of domestic legislation on the said date was confirmed by two side letters, one from José Ramos-Horta confirming East Timor's position, and the other from Alexander Downer confirming Australia's position. This has been argued to be unfair to East Timor as it legitimises Australia's exploitation of petroleum in the disputed areas outside the Joint Petroleum Development Area established under the Timor Sea Treaty.[12]

Timor Sea Treaty terms stay

[edit]The terms of the Joint Petroleum Development Area established under the Timor Sea Treaty will continue to be applied over the said area.[14]

Negotiations for permanent boundaries

[edit]Both parties are not obliged to negotiate permanent maritime boundaries for the period of the treaty.[15]

Division of Greater Sunrise' revenues

[edit]Both countries will share the upstream (valued as at oil well) revenue from the Greater Sunrise field on a 50:50 basis.[16] The upstream value of the petroleum shall be determined at "arm's length" basis.[17] The increase in East Timor's share on the proceeds from Greater Sunrise from 18.1% to 50% could be said [citation needed] to be the result of pressure based on East Timor's argument that the field was located closer to it than Australia and should therefore belong to it, a position claimed in submissions to the Australian Joint Standing Committee on Treaties in 2007, by which a 50% share is still not adequate for East Timor.[18][19] According to this position, if a maritime boundary were established along the median line between the coasts of the two countries, the current prevailing practice, all of Greater Sunrise would be in Timor-Leste's territory. However, another source indicates that the part of Greater Sunrise that lies outside of East Timor's current jurisdiction, while indeed closer to East Timor than to Australia, is also closer to Indonesia than to East Timor [20] and thus would not be in East Timor's territory.

As for the method of payment, Australia is to pay East Timor half the total revenue earned by itself and East Timor less the amount of revenue earned by East Timor. On the event East Timor's revenue exceeds that of Australia, no payment will be made by East Timor but subsequent payments by Australia to East Timor shall be adjusted accordingly.[21]

Each party can request the appointment of an assessor to determine the amount of revenue earned by either country.[22]

Treaties governing petroleum resources exploitation

[edit]All obligations related to exploring and exploiting for petroleum by Australia and East Timor for the duration of CMATS shall be governed by CMATS, Timor Sea Treaty, Sunrise International Unitization Agreement and any future agreement drawn up pursuant to the Timor Sea Treaty. CMATS however does not revoke the Timor Sea Treaty or the Sunrise IUA.[23]

Water column jurisdiction

[edit]East Timor shall have "sovereign rights" over the water column north of the southern border of the Joint Petroleum Development Area established under the Timor Sea Treaty while Australia gains "sovereign rights" over the water column south of the line. The coordinates of the line is determined in Annex II of the treaty.[24]

| Point | Longitude (E) | Latitude (S) |

|---|---|---|

| Water column jurisdiction line in Annex II | ||

| 1 | 126° 31' 58.4" | 11° 20' 02.9" |

| 2 | 126° 47' 08.4" | 11° 19' 40.9" |

| 3 | 126° 57' 11.4" | 11° 17' 30.9" |

| 4 | 126° 58' 17.4" | 11° 17' 24.9" |

| 5 | 127° 31' 37.4" | 11° 14' 18.9" |

| 6 | 127° 47' 08.4" | 10° 55' 20.8" |

| 7 | 127° 48' 49.4" | 10° 53' 36.8" |

| 8 | 127° 59' 20.4" | 10° 43' 37.8" |

| 9 | 128° 12' 28.4" | 10° 29' 11.8" |

Timor-Leste/Australia Maritime Commission

[edit]A Maritime Commission comprising one minister each appointed by the two countries. The commission should meet at least once a year.[25]

No further re-apportionment of Greater Sunrise revenue

[edit]The parties agree not to re-determine the apportionment ratio of the Greater Sunrise field for the period the treaty is in force.[26]

Duration of CMATS

[edit]CMATS shall remain in force for 50 years after its entry into force, which was on February 22, 2057, or five years after the exploitation of the Greater Sunrise field ceases, whichever earlier. Either East Timor or Australia can terminate most of CMATS if a development plan for the Greater Sunrise field is not approved within six years after its entry into force, or if production of petroleum from the field does not commence within 10 years after the date of entry into force of this Treaty. Should petroleum production take place in the Greater Sunrise field after the termination of CMATS, all the terms of this treaty shall come back into force and operate from the date of commencement of production.[27] No development plan had been approved by 23 February 2013, six years after CMATS came into force, and Timor-Leste was weighing whether to give notice of termination.[28]

Entry into force

[edit]CMATS will enter into force after an exchange of notes by both parties that their respective parliaments have ratified the treaty. The exchange of notes occurred on February 23, 2007.

East Timor's parliament ratified the treaty on February 20, 2007. CMATS was tabled in the Australian parliament on the first sitting day of 2007 on February 6, 2007, and on February 22, 2007, just before the exchange of notes with East Timor, Minister for Foreign Affairs Alexander Downer wrote to inform the parliament's Joint Standing Committee on Treaties of his decision to invoke the national interest exemption, to speed up ratification of the treaty by not first referring it to the Joint Committee.[29]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Full text of treaty available at the Australasian Legal Information Institute's Australian Treaty Series database [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ "'Matter of death and life': Espionage in East Timor and Australia's diplomatic bungle". ABC News. 25 November 2015.

- ^ "East Timor tears up oil and gas treaty with Australia". ABC News. 9 January 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ "Australia and East Timor agree on border, revenue from offshore gas fields". ABC News. 26 February 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ CMATS Article 2

- ^ Article 3

- ^ Article 4(1)

- ^ Article 4(4)

- ^ Article 4(5)

- ^ Article 4(6)

- ^ "Australia-East Timor Certain Maritime Arrangements Treaty", Joint Standing Committee on Treaties Report, 85, 21 June 2007

- ^ a b "The CMATS Treaty", The La'o Hamutuk Bulletin, 7 (1), April 2006

- ^ Article 4(2)

- ^ Article 4(3)

- ^ Article 4(7)

- ^ Article 5(1)

- ^ Article 5(2)

- ^ Submissions to the Australian Joint Standing Committee on Treaties, 2007 from: Dr Clinton Fernandes and Dr Scott Burchill, Submission 2; ETAN, Submission 3; Timor Sea Justice Campaign, Submission 5; Mr Rob Wesley-Smith, Submission 7; La'o Hamutuk, Submission 8. Timor Sea Justice Campaign, Submission 5, p. 1. Timor Sea Justice Campaign, Submission 5, p. 2.

- ^ "JSCOT Report 85, Chapter 6 - Australia-East Timor Certain Maritime Arrangements Treaty".

- ^ "Maritime Boundaries in the Timor Sea". Hydrographer.org. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Articles 5(9) and 5(10)

- ^ Article 6

- ^ Article 7

- ^ Article 8

- ^ Article 9

- ^ Article 10

- ^ Article 12.3

- ^ "2012-2016: Protesting the CMATS Treaty to compel boundary negotiations".

- ^ Robert J. King, “The Timor Gap, 1972-2017”, March 2017. Submission No.27 to the inquiry by the Australian Parliament Joint Standing Committee on Treaties into Certain Maritime Arrangements - Timor-Leste. p.67. [2]

Further reading

[edit]- Leach, Michael (6 December 2013). "Turbulence in the Timor Sea". Inside Story. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ——————— (4 September 2017). "Bridging the Timor Gap". Inside Story. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ——————— (8 March 2018). "Timor-Leste: architect of its own Sunrise". Inside Story. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- McGrath, Kim (2017). Crossing the Line: Australia's Secret History in the Timor Sea. Carlton, Vic: Black Inc. ISBN 9781863959360.

- Schofield, Clive; Strating, Bec (30 March 2018). "Sun setting on Timor-Leste's Greater Sunrise plan". East Asia Forum. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- Strating, Bec (4 June 2016). "Unravelling Timor-Leste's Greater Sunrise strategy". East Asia Forum. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- —————— (28 January 2017). "Timor-Leste's maritime ambitions risk all". East Asia Forum. Retrieved 20 January 2022.