Yusuf and Zulaikha

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2014) |

"Yusuf and Zulaikha" (the English transliteration of both names varies greatly) refers to a medieval Islamic version of the story of the prophet Yusuf and Potiphar's wife which has been for centuries in the Muslim world, and is found in many languages such as Arabic, Persian, Bengali, Turkish, Punjabi and Urdu. Its most famous version was written in the Persian language by Jami (1414–1492), in his Haft Awrang ('Seven Thrones').

In the Qur'an

The story of Yusuf and Zulaikha takes place in the twelfth chapter of the Qur’an, titled "Yusuf." The story plays a primary role within the chapter, and begins after Yusuf, son of Yaqub ibn Ishaq ibn Ibrahim, is abandoned and subsequently sold to an Egyptian royal guard.[1]

After reaching maturity, Yusuf becomes so beautiful that his master's wife, later called Zulaikha in the Islamic tradition, falls in love with him. Blinded by her desire, she locks him in a room with her and attempts to seduce him.[2] Through his great wisdom and power, Yusuf resists her and turns around to open the door. Upset, Zulaikha attempts to stop him, and in the process, rips the back of his shirt.[3] At this moment, Zulaikha's husband (the lord of the house and Yusuf's master) catches Zulaikha and Yusuf struggling at the door and calls for an explanation.[4] Deflecting the blame, Zulaikha tells her husband that Yusuf attempted to seduce her.[5] Yusuf contradicts this and tells the lord that Zulaikha wanted to seduce him.[6] Unsure who is guilty, a servant of the household tells the lord that the placement of the rip on Yusuf's shirt will tell the truth about what happened. According to the servant, if Yusuf's shirt was ripped at the front, he must have been going toward Zulaikha, attempting to seduce her.[7] On the other hand, if Yusuf's shirt was ripped from the back, he was trying to get away from Zulaikha; therefore, Zulaikha was guilty.[8] After examining Yusuf's shirt and seeing the rip on the back, Yusuf's master determines his wife is the guilty party, and angrily tells her to ask forgiveness for her sin.[9]

Later, Zulaikha overhears a group of women speaking about the incident, verbally shaming Zulaikha for what she did.[10] Zulaikha, angered by this, gives each woman a knife and calls for Yusuf.[11] Upon his arrival, the women cut themselves with their knives, shocked by his beauty.[12] Zulaikha, boosted by proving to the women that any woman would fall for Yusuf, proudly claims that Yusuf must accept her advances, or he will be imprisoned.[13]

Disturbed by Zulaikha's claim, Yusuf prays to Allah, begging Allah to make them imprison him, as Yusuf would rather go to jail than do the bidding of Zulaikha and the other women.[14] Allah, listening to Yusuf's request, makes the chief in power believe Yusuf should go to prison for some time, and so Yusuf does.[15]

In poetry

Jami

In 1483 AD, the renowned poet, Jami, wrote his interpretation of the allegorical romance and religious texts of Yusuf and Zulaikha. It became a classical example and the most famous version of Sufi interpretation of Qur’anic narrative material. Jami's example shows how a religious community takes a story from a sacred text and appropriate it in a religious-socio-cultural setting that is different from the original version. Therefore, it is known as a masterpiece of Sufi mystical poetry.[16]

Jami opens the poem with a prayer.[17] In the narrative, Yusuf is an incredibly handsome young man. Due to his beauty, he became a victim of his brothers' jealousy because Yusuf was so beautiful he had an influence on everyone that met him. The brothers take him to be sold to the in a slave market in Egypt.[18] Jami shows that Yusuf's brothers' greed is not how to live a Sufi life. Yusuf is put up for sale and astounds everyone with his beauty. This causes a commotion in the market and the crowd starts bidding for him. Zulaikha, the rich and beautiful wife of Potiphar, sees him and is struck by Yusuf's beauty. She outbids everyone and buys him.[19]

For years, Zulaikha suppressed her desire for Yusuf until she could not resist it any longer. She ends up attempting to seduce Yusuf. When Potiphar found out, he sent Yusuf to prison causing Zulaikha to live with extreme guilt.[20] One day while in prison, Yusuf was able to interpret the Pharaoh's dream, and thus, the Pharaoh made Yusuf chief of all his treasures.[21] Because of this, Yusuf was able to meet with Zulaikha. He saw that she still had love for him and was miserable. He took her in her arms and prayed to God. The prayer and the love Yusuf and Zulaikha had for each other attracted a blessing from God. Restoring youth and beauty to Zulaikha. They got married and lived happily.[22]

What the audience learns from this story is that God's beauty appears in many forms and that Zulaikha's pursuit of love from Yusuf is, in fact, the love and pursuit of God.[23] In Jami's version, Zulaikha is the main character and even more important thematically and narratively than Yusuf. Yusuf, on the other hand, is a two-dimensional character. Another difference in Jami's version is that the overwhelming majority of the story is unrelated to the Qur’an. Finally, Jami claims that his inspiration to write this version of the story comes from love.[24]

Shah Muhammad Saghir

As Islam continued to spread, authors across Asia resonated with the story of Yusuf and Zulaikha. Jami's adaptation of the famous tale served as the model for many writers. Bengali author Shah Muhammad Saghir also published his own reinterpretation. Though little information is available about his life and the sources from which he drew, it is assumed to have been written between 1389 and 1409.[25] Through this work, he set the precedent for romance in Bengali literature. One of the unique attributes of Sagir's version is the change of setting, as his poem takes place in Bengal. A prime example of syncretism, it blends elements of Hindu culture with the classic Islamic tale, which in turn encourages readers to coexist with other faiths. It is also testament to Islamic influence on the Indian subcontinent. It is known for its detailed descriptions of Yusuf and Zulaikha's physical beauty, and begins with the two protagonists' childhoods, which then unravels into a tale full of passion and pursuit.[26] Sagir's Yusuf-Zulekha also keeps in touch with the Islamic values found in the original story and echoes the Sufi belief that to love on earth is to love Allah. Although Sagir intended his poem not to be read as a translation of the Quranic version nor as sourced from the Persians before him, he did borrow Persian linguistic traditions in order to write it.[27] Following the introduction of Sagir's poem, other Bengali writers throughout the centuries took inspiration and created their own versions of Yusuf and Zulaikha, including Abdul Hakim and Shah Garibullah. Hakim took his inspiration directly from Jami, while Garibullah chose to write something more unique.[28]

Other versions

There also exists a Punjabi Qisse version of Yusuf and Zulaikha, composed by Hafiz Barkhurdar, that contains around 1200 pairs of rhyming verses.[29] He, too, was inspired by Jami, while incorporating his own stylistic choices. In Barkhurdar's version, Yusuf is reunited with his father, Yaqub at the end.[30] This is an example of a written qissa, or a Punjabi style of storytelling that emphasizes folkloric tradition. Barkhurdar's rendition was not published until the nineteenth century, and by then it was considered too antiquated for mainstream reading.[31] In fact, many versions of Yusuf and Zulaikha have been lost to time. However, the popularity of the story can be used to measure the impact of Persianization on South Asia]]. This is evident in Maulvi Abd al-Hakim's interpretation of Yusuf and Zulaikha, which directly imitates Jami as well as other features of the Persian language. Nevertheless, these stories contributed to the development of the 'qissa' as a genre.

Based on Jami's Persian version, Munshi Sadeq Ali also wrote this story as a poetic-style puthi in the Sylheti Nagari script, which he titled Mahabbatnama.[32]

A version by Mahmud Qırımlı from 13th century is regarded as the first literary work written in the Crimean Tatar language.[33] Another writer who retold the story is Mahmud Gami in Kashmiri.

In art

The international recognition of the tale of Yusuf and Zulaikha resulted in many artistic renditions of the poem. Substantial periods of conquest and dissolution of Islam throughout

Asia and North Africa led to a flurry of diverse artistic interpretations of Yusuf and Zulaikha.

Central Asia

Within one of the wealthiest trading centers along the Silk Road in Bukhara, Uzbekistan, the manuscript of Bustan of Sa’di would be found.[34] The status of Bukhara as a wealthy Islamic trading hub led to a flourishing of art and culture in the city. From such an economic boom the Bustan of Sa’di created in 1257 C.E portrays many scenes from the poems of Yusuf and Zulaikha. In a frequently reproduced scene, Yusuf leaves the home of Zulaikha after refusing her romantic advances. The scene demonstrated visually a prominent theme from the poem in which we see Yusuf's powerful faith in God overcome his own physical desires. As depicted in the artwork, the locked doors unexpectedly spring open, offering Yusuf a path from Zulaikha's home. In crafting this piece the materials used fall in line with the conventional methods used at the time and were a mixture of oil paints, gold and watercolors.

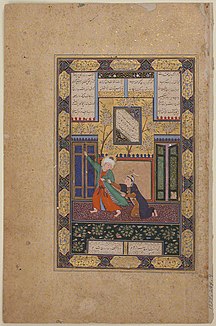

Persia

From Persia we see what is considered to be, by some experts, the most recognized Illustration of Jami's poem Yusuf and Zulaikha. The artist Kamāl al-Dīn Behzād under the direction of Sultan Husayn Bayqara of the Timurid Empire) constructed a manuscript illustrating the tale of Yusuf and Zulaikha. Behzād has often been credited with initiating a high point of Islamic miniature painting. His artistic style of blending the traditional geometric shape with open spaces to create a central view of his characters was a new idea evident in many of his works.[35] One of Behzhad's most notable works had been his interpretation of the Seduction of Yusuf, where his distinctive style of painting is on display.[36] The painting depicts dynamic movement, with Yusuf and Zulaikha both painted while in motion amidst a backdrop of a stretched out flat background to bring attention to the characters central to the painting.

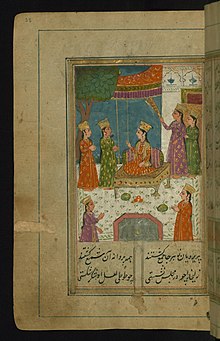

Kashmir

In a work originating from the Kashmir region of India, we see how under the Islamic Mughal Empire the renowned poem of Yusuf and Zulaikha continued to flourish in art.[37] The continued interest in illustrating the renowned tale of Yusuf and Zulaikha can be found in a manuscript from Muhhamid Murak dating back to the year 1776. The manuscript offers over 30 paintings styling different scenes from Jami's poem of Yusuf and Zulaikha.[38] Within the manuscript, the unique style of the Mughal painting that had combined Indian and Persian artistic style is demonstrated.[39] There is more emphasis upon realism in Mughal painting and this focus may be seen within Murak's manuscript. The illustration of Zulaikha and her maids offers the viewer a detail oriented scope into the author's imagining of the tale. The historically accurate dress and photorealistic design differ from prior interpretations of the tale which had been more fantastical in nature.

References

- ^ The Holy Qur’an 12:22 (Translated by Malik Ghulan Farid)

- ^ The Holy Qur’an 12:24-25

- ^ The Holy Qur’an 12:26

- ^ The Holy Qur’an 12;26

- ^ The Holy Qur’an 12:26

- ^ The Holy Qur’an 12:27

- ^ The Holy Qur’an 12:27

- ^ The Holy Qur’an 12:28

- ^ The Holy Qur’an 12:30

- ^ The Holy Qur’an 12:31

- ^ The Holy Qur’an 12:32

- ^ The Holy Qur’an 12:32

- ^ The Holy Qur’an 12:33

- ^ The Holy Qur’an 12: 34

- ^ The Holy Qur’an 12:36

- ^ Beutel, David. "Jami's Yusuf and Zulaikha: A Study in the Method of Appropriation of Sacred Text." Beutel. Accessed November 18, 2022. http://beutel.narod.ru/write/yusuf.htm .

- ^ Griffith, Ralph T.H., Yúsuf And Zulaikha: A Poem by Jámi, London: Routledge, 2000,13-15.

- ^ Griffith, Yúsuf And Zulaikha: A Poem by Jámi, 36-38

- ^ Griffith, Yúsuf And Zulaikha: A Poem by Jámi, 46-49.

- ^ Griffith, Yúsuf And Zulaikha: A Poem by Jámi, 49-52.

- ^ Griffith, Yúsuf And Zulaikha: A Poem by Jámi, 264-269.

- ^ Griffith, Yúsuf And Zulaikha: A Poem by Jámi, 292-296.

- ^ Beutel, "Jami's Yusuf and Zulaikha: A Study in the Method of Appropriation of Sacred Text."

- ^ Beute, "Jami's Yusuf and Zulaikha: A Study in the Method of Appropriation of Sacred Text."

- ^ Abu Musa Mohammad Arif Billah, Influence of Persian Literature on Shah Muhammad Sagir's Yusuf Zulaikha and Alaol's Padmavati, 2014: 101

- ^ Billah, Influence of Persian Literature, 97

- ^ Billah, Influence of Persian Literature, 100-101

- ^ Billah, Influence of Persian Literature, 119

- ^ Christopher Shackle, "Between Scripture and Romance: The Yusuf-Zulaikha Story in Panjabi", South Asia Research 15, no. 2 (1995): 164

- ^ Shackle, "Between Scripture and Romance", 166

- ^ Shackle, "Between Scripture and Romance",166

- ^ Saleem, Mustafa (30 Nov 2018). "মহব্বত নামা : ফার্সি থেকে বাংলা আখ্যান". Bhorer Kagoj.

- ^ Кримськотатарська література — ЕСУ

- ^ "Yusuf and Zulaikha’, Folio 51r from a Bustan of Sa`Di." Metmuseum.org. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/452672 .

- ^ Roxburgh, David J, "Kamal Al-Din Bihzad and Authorship in Persianate Painting," Muqarnas 17 (2000): 119–46. doi:10.2307/1523294.

- ^ Roxburgh, David J., "Kamal al-Din Bihzad and Authorship in Persianate Painting," Muqarnas, Vol. XVII, 2000.

- ^ "Zulaykha in the Company of Her Maids," The Walters Art Museum, Online Collection of the Walters Art Museum, August 1, 2022. https://art.thewalters.org/detail/83831/zulaykha-in-the-company-of-her-maids/ .

- ^ "Zulaykha in the Company of Her Maids," The Walters Art Museum.

- ^ Titley, Norah M., Persian Miniature Painting, and its Influence on the Art of Turkey and India (Austin : University of Texas Press, 1984).

Bibliography

- Abu Musa Mohammad Arif Billah. Influence of Persian Literature on Shah Muhammad Sagir's Yusuf Zulaikha and Alaol's Padmavati. 2014.

- Beutel, David. "Jami's Yusuf and Zulaikha: A Study in the Method of Appropriation of Sacred Text." Beutel. Accessed November 18, 2022. http://beutel.narod.ru/write/yusuf.htm.

- Christopher Shackle. "Between Scripture and Romance: The Yusuf-Zulaikha Story in Panjabi." South Asia Research 15, no. 2 (1995).

- Griffith, Ralph T.H., Yúsuf And Zulaikha: A Poem by Jámi, London: Routledge, 2000.

- Titley, Norah M.. Persian Miniature Painting, and its Influence on the Art of Turkey and India. Austin : University of Texas Press, 1984.

- Roxburgh, David J. "Kamal Al-Din Bihzad and Authorship in Persianate Painting." Muqarnas 17 (2000). https://doi.org/10.2307/1523294.

- "Yusuf and Zulaikha’, Folio 51r from a Bustan of Sa`Di." Metmuseum.org. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/452672.

- "Zulaykha in the Company of Her Maids: The Walters Art Museum." Online Collection of the Walters Art Museum, August 1, 2022. https://art.thewalters.org/detail/83831/zulaykha-in-the-company-of-her-maids/.

More Information

- "English translation of Jami's Joseph and Zuleika (edited by Charles Horne, 1917)" (PDF). (138 KiB)

- Women Writers, Islam, and the Ghost of Zulaikha, by Elif Shafak

- Manuscript text Yusuf und Zalikha[permanent dead link] in the collection of Museums für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (MKG 1916.35)

- Jāmī in Regional Contexts: The Reception of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Jāmī's Works in the Islamicate World, ca. 9th/15th-14th/20th Century Series: Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 1 The Near and Middle East, Volume: 128 Editors: Thibaut d'Hubert and Alexandre Papas, with five chapters on the Yusuf and Zuleykha story:

- Foundational Maḥabbat-nāmas: Jāmī's Yūsuf u Zulaykhā in Bengal (ca. 16th–19th AD) By: Thibaut d’Hubert Pages: 649–691

- Love's New Pavilions: Śāhā Mohāmmad Chagīr's Retelling of Yūsuf va Zulaykhā in Early Modern Bengal By: Ayesha A. Irani Pages: 692–751

- Śrīvara's Kathākautuka: Cosmology, Translation, and the Life of a Text in Sultanate Kashmir By: Luther Obrock Pages: 752–776

- A Bounty of Gems: Yūsuf u Zulaykhā in Pashto By: C. Ryan Perkins Pages: 777–797

- Sweetening the Heavy Georgian Tongue Jāmī in the Georgian-Persianate World By: Rebecca Ruth Gould Pages: 798–828