Assassination of Ivan Stambolić

Ivan Stambolić | |

|---|---|

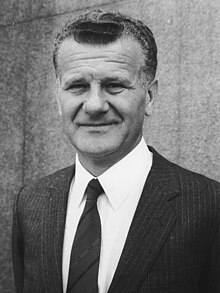

Ivan Stambolić, May 1986 | |

| 12th President of Serbia As President of the Presidency of SR Serbia | |

| In office 5 May 1986 – 14 December 1987 | |

| 56th Prime Minister of Serbia As President of the Executive Council of Serbia | |

| In office 6 May 1978 – 5 May 1982 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 November 1936 Brezova, Drina Banovina, Kingdom of Yugoslavia |

| Died | 25 August 2000 (aged 63) Fruška Gora, Serbia, Federal Republic of Yugoslavia |

| Manner of death | Assassination |

| Resting place | Topčider, Belgrade, Serbia |

| Nationality | Serbian |

| Political party | League of Communists of Yugoslavia |

| Spouse |

Katarina Zivojinovic

(m. 1962) |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives | Petar Stambolić (uncle) |

| Alma mater | University of Belgrade |

Ivan Stambolić was a Serbian politician. In his career he rose to become the president of Yugoslavia. In August 2000 he was assassinated just before a national, pivotal election,[1] the event itself and reasoning for which is extremely important in understanding some of the events that occurred before the Yugoslav Wars.

Political career

Ivan Stambolić was the 56th prime minister of Serbia from May 1978 – 1982, and at one point rose to the presidency of Serbia in 1986; he was the 12th president of Serbia during an extremely important time in the break-up of the former Yugoslavia.

One of the most important relationships prior to the Yugoslav Wars was that between himself and Slobodan Milošević. He had been called a close personal friend[2] of Milošević, the main actor thought to be responsible for the assassination and for many of the horrors that occurred during the Yugoslav Wars. He had "supported him through elections" to become the new leader of the League of Communists of Serbia. He reportedly spent several days advocating to members of the League of Communists for Milošević, securing him a victory and allowing him to become the president of the League of Communists of Serbia.[3] The two had similar ideologies which led to a mutually beneficial relationship at first.

This political and personal relationship is how his career came to an abrupt end in 1988. Milošević ousted him from the Serbian State presidency.[2] He remained quiet on the political stage, mainly working in an advisory role after the Yugoslav Wars. He disappeared on 25 August 2000 under strange circumstances, which turned out to be a politically motivated assassination.[4]

Assassination

Disappearance

It was widely reported that several members of a Special Operations Unit were involved in Stambolić's disappearance and were later tried and convicted.[5] Details from police reports suggest that “Mr Stambolić failed to return from a morning jog a month before a Yugoslavian presidential election, at which some expected him to challenge Milošević. Police blamed his former protege for the murder".[6] It is fairly clear that Milošević had a hand in his disappearance. The truth was uncovered years later. "His remains have been dug out of a pit in Mount Fruška Gora", said Mr Mihailovic. Fruška Gora is a national park south of Novi Sad. "He was executed with two shots and buried in a quicklime pit dug out in advance",[4] and under the circumstances that saw Stambolić be sidelined by his former best friend as he "gave warning of the dangers of nationalism".[6]

Prosecution

The men, several members of the Special Operations Unit, who conducted the killing of Stambolić were the first to be sentenced. There was another attempted murder of the leader of the opposition to Milošević at the time, Vuk Draskovic.[5]

Milorad Ulemek was among the first convicted in 2000: "a popular ex-communist, whilst also being convicted for the attempted assassination of Draskovic, and for an even earlier attempt on Draskovic....Ulemek is found guilty of creating a criminal enterprise on the orders of Slobodan Milošević... Ulemek's co-accused, five fellow members of the so-called Red Berets secret police unit and another senior secret police officer, were sentenced to between four and 40 years for their roles in the crime."[5]

Slobodan Milošević never officially served any time for his actions. It is noted here that in a phone interview with Ivan Stambolić’s son, Veljko Stambolić, said "I do think that a 40-year prison term is an adequate sentence for the executioners, however, those who gave orders need to be punished as well."[7] Milošević awaited justice concerning the underground violence until his trial for war crimes had finished at the Hague. Although the comments from Veljko Stambolic were made before 2006 when Milošević died awaiting justice at the Hague, Milošević was eventually convicted for his crimes by the Supreme Court, essentially accepting the ruling that had been previously put forth by the Special Court for Organised Crime in Belgrade.

Relationship with Slobodan Milošević

In the amended indictment of Slobodan Milošević at the international criminal tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, it is clear that Milošević was prosecuted for ordering both the killings,[8] one successful, one not. What led to this, his differences with his previous mentor and the circumstances of their relationship are essential in detailing why he was assassinated.

The bedrock of the conflict with Milošević was that Stambolić always remained a true Yugoslav. On many occasions Stambolić was seen to show negative sentiments towards the rising "nationalist" ideology, in many instances warning of the dangers.[2] As an authoritarian leader Milošević had his pathway clear cut. His personal deficiencies, were seen to be too large to mend this rift between them. Milošević now saw his former companion now the ultimate adversary in the Serbian political field.

It is said that since being ousted by former Milošević that Stambolić's political career was over, yet it is clear his journey was not complete. Stambolić was always considered more than a "sidelined" Serbian intellectual and politician.[9] Despite this the Stambolić family claimed he no longer had any enemies of any sort.[9] Slobodan Milošević first rose to power during the time frame of the Stambolić presidency, and then was ousted by him. Why and how did this happen?

Yugoslav communist revolutionary Josip Broz Tito was the president of Yugoslavia from 14 January 1953 until his death on 4 May 1980. He was an extremely strong leader who many thought responsible for holding the ethnically diverse nations of Yugoslavia together for his 27-year term as president. Kosovo, an area populated by mostly Kosovar Albanians with a minority of Serbians, was getting more and more contentious since the death of Tito.[10] The years from 1980-1986 involved Kosovo Albanian riots, the desecration of Serbian Orthodox architecture and graveyards. In reaction to this Stambolić sent Milošević to quell the ever-growing unrest in Tito's absence.[9] This was probably the first sign of a rift in their ideologies. No matter what, the Serbs were going to seek to stay in the region. In his speech at Kosovo Polje, Milošević delivered a much different message than Stambolić's desire to bring the region together. Milošević's perspective was fiercely nationalist, who ended his speech with:

"Rest assured, this is a feeling that is uplifting all of Yugoslavia. All of Yugoslavia is with you. The issue isn't that it's a problem for Yugoslavia, but Yugoslavia and Kosovo. Yugoslavia doesn't exist without Kosovo! Yugoslavia would disintegrate without Kosovo! ... Yugoslavia and Serbia will never give up Kosovo!"[11]

"Unless you fight for Serbia, your ancestors will be betrayed, your descendants will be shamed. These are your lands, your fields, your gardens, your memories."[12]

That speech alone had extreme consequences, of which his predecessors had been keenly aware. Such nationalism had been banned under the reign of Tito, for good reason.[13] It had in fact been seen as Tito's greatest strength. Managing to maintain unity and quell potentially devastating nationalist insurrections helped him to guide Yugoslavia[13] through various tipping points in the regions history such as the Croatian Spring, something Milošević clearly had no interest in. Under Tito "it was a forbidden topic at that time. No nationalism was ever permitted in Yugoslavia. And Serb nationalism was the first one to arise, to be raised, to be put on the agenda by Mr Milosevic, and that caused a sort of scandal."[9]

Stambolić publicly scolded Milošević for the speech once he returned home as a nationalist hero.[9] He had claimed after the fact that he saw that event as "the end of Yugoslavia".[14] Retaliation was quick: Milošević purged the Serbian Communist Party in 1987,[15] after which the party ousted Stambolić, making him president of the Yugoslav Bank for International Economic Cooperation, now known as JUBMES banka. This is not to say Stambolić did not antagonise his former protégé. In 1995, during his time with the bank he joined the Serbian Civil Council along with together with Miladin Životić, Miša Nikolić, Žarko Korač, Rasim Ljajić, and Nenad Čanak, which attempted to create the Social Democratic Alliance of Serbia prior to the 1996 federal election.[4]

JUBMES was swallowed up by the federal government in 1997 and Miodrag Zecevic, a Serbian Statesmen, became the new director. The bank published harsh criticisms of former adversaries. On 8 April 2000 he released a statement detailing the fall of Slobodan Milošević. A translation of a quote is detailed here: "his fall will be difficult and dramatic, because the Yugoslav president," big and powerful "only thanks to the available forces of repression."[4] During his time with the bank he continued to speak on this former protégé, further antagonising him by travelling to Montenegro on multiple occasions to meet with political rivals of Milošević.[4]

Ljubica Markovic, director at beta news agency with ties to Stambolić, claimed that despite Stambolić's previous stances concerning the free press during his time as president, his name had appeared in opinion polls leading up to the pivotal 2000 election.[9] The reality of this threat was low. The Stambolić family lawyer has made the argument that the "well-connected Mr Stambolić remained at least a potential threat to Mr Milošević – particularly in the wake of the Kosovo conflict of 1999 when Serbia under its authoritarian leader seemed destined to linger in continuing international isolation”.[16]

External links

- International criminal tribunal for the former Yugoslavia: amended indictment

- Milošević speech at Kosovo Polje

- https://www.rferl.org/a/1066641.html

- http://www.b92.net/specijal/stambolic/&prev=search

- http://www.icty.org/x/cases/slobodan_milosevic/ind/en/mil-ai010629e.htm

- http://www.wou.edu/history/files/2015/08/Daniel-Van-Winkle.pdf

Further reading

- Doder, Dusko; Branson, Louise, Milosevic : portrait of a tyrant / Dusko Doder and Louise Branson, Free Press

- Brown, Gary, 1950-; Australia. Department of the Parliamentary Library. Information and Research Services (1999), The Yugoslav war: where to now? / Gary Brown, Dept. of the Parliamentary Library

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Ianziti, Gary; Cicic, Muris (1997), Bosnia-Herzegovina in the Yugoslav aftermath : essays on the causes and consequences of the Balkan conflicts, 1992-1994 / edited by Gary Ianziti and Muris Cicic, Queensland University of Technology

References

- ^ Tordovic, Alex (1 September 2000). "Disappearance Raises Fears in Serbia / Milosevic suspected in case of ex-leader". SFGate. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Partos, Garbriel (19 March 2003). "Ivan Stambolic: Mentor of Milosevic stabbed in the back by his protege". The Independent. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ "Timeline: The Political Career Of Slobodan Milosevic". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 13 March 2006. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Press release of the Serbian Ministry of Interior". B92. 28 March 2003. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ a b c "40 years for Stambolic murder". SBS News. 22 August 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ a b Torodovic, Alex (29 March 2003). "Ex-Serbian president's body found in forest". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ Wood, Nicholas (19 July 2005). "Milosevic Aides Found Guilty of Yugoslav Political Assassination". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ del Ponte, Carla (29 June 2001). "The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia: Amended Indictment". The International Criminal Tribune for the Former Yugoslavia. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Hill, Don (8 August 2000). "Yugoslavia: Missing Serb Leader Was 'Man Who Invented Milosevic'". Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Morgan, Dan (16 June 1999). "One Nation Under Tito". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ Skorick, Tim (1987). "Speech of Slobodan Milosevic at Kosovo Polje". www.Slobodan-Milosevic.org. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ Hill, Don (9 June 1999). "Yugoslavia: Psychiatrist Says Milosevic Programmed For Martyred Defeat". Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ a b Ryan Van Winkle, Daniel (2005). The Rise of Ethnic Nationalism in the Former Socialist Federation of Yugoslavia: An Examination of the Use of History. Western Oregon: Western Oregon University. pp. 13–17 29–33.

- ^ Ward, Victoria (26 May 2011). "Serbian war criminals: Slobodan Milosevic profile". The Telegraph. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ "The rise and fall of Milosevic". The Sydney Morning Herald. 12 March 2006. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Partos, Gabriel (23 February 2003). "Analysis: Stambolic murder trial". BBC News. Retrieved 5 May 2019.