Let Her Fly

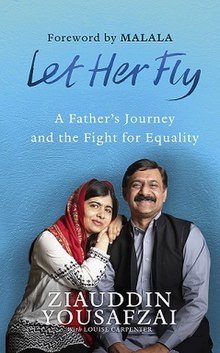

Front cover | |

| Author | Ziauddin Yousafzai |

|---|---|

| Subject | Autobiography |

| Publisher | W. H. Allen & Co. |

Publication date | 8 November 2018 |

| Publication place | United States |

Let Her Fly: A Father's Journey and the Fight for Equality is a 2018 autobiography by Ziauddin Yousafzai, the father of the Pakistani activist for female education Malala Yousafzai. It details the oppression he saw women face in Pakistan, his family life both before and after his daughter Malala was shot by the Taliban and his attitudes to being a brother, a husband and a father.

Background

Ziauddin Yousafzai is a Pakistani education activist. He has three children, a daughter—Malala Yousafzai—and two sons—Khushal and Atal. After writing an anonymous blog for BBC Urdu and being subject to a New York Times documentary Class Dismissed, Malala began gaining a public profile as an advocate for female education and for speaking about the conditions of life under the growing influence of the Taliban.[1][2][3][4] She began receiving death threats, as did her father, and on 9 October 2012, a member of the Taliban shot Malala as she was taking a bus from school to her home.[5][6] Her continuing activism led her to become the youngest Nobel Prize laureate at the age of 17 by winning the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize.[7] In 2013, Yousafzai co-wrote the memoir I Am Malala with Christina Lamb.[8]

Ziauddin Yousafzai said that I Am Malala covered "one part of [his] life, a daughter's father", and Let Her Fly was written to detail other parts such as being "the brother of five sisters who had never been to school, the husband of a wife and the father of two sons". He described it as following a "transformation" from "a member of a patriarchal society" to his present self.[9] Yousafzai said that the title "means let every girl fly, in every corner of the world".[10] It originated from his answer to the common question of what he did to raise a successful daughter: "ask what I did not do. I did not clip her wings. I let her be herself".[11][12] The book was published on 8 November 2018 by W. H. Allen & Co.[13][14]

Synopsis

As a child, Yousafzai had a stammer, was dark-skinned and not from a wealthy family; he was bullied at school. His imam father, who believed in the importance of male education, was disappointed that he did not become a doctor. Yousafzai had two particularly formative experiences with women's oppression in his childhood: a cousin of his was shot after leaving an abusive husband; and a girl in his village was murdered in an honour killing for loving a boy her family disapproved of. The book quotes a poem Yousafzai wrote aged 20, addressed to a hypothetical future daughter of his.

Yousafzai pursued a master's degree and began a relationship with his future wife, Toor Pekai. He aimed for his wife to have more freedom and equality than most wives in his community. With around ₨15,000 (£100), he founded a school which began with only three students. His focus was on girls' education. He worked in a large primary school and high schools; with his daughter, he would travel and talk about the value of female schooling. After Malala was shot, she was taken to a hospital in the United Kingdom, where the family had to remain. Yousafzai found it difficult to raise his sons in the UK, viewing them as less obedient than he was as a child, but he became gradually less controlling of them.

Reception

Daily Times's Shama Junejo recommended the book for all audiences, but particularly young girls and "those who believe that behind every great feminist woman there is always a great father, husband, brother or a son".[15] In a review jointly published by Cape Times and Pretoria News, a writer lauded that the book has a "monumental" impact and will "inspire, move and enlighten" a "broad readership". The reviewer had "tears of awe, joy and admiration" while reading.[16][17] The Hindu summarised: "Told through intimate portraits of each of Mr. Ziauddin's closest relationships ... the book looks at what it means to love, to have courage and fight for what is inherently right".[18] Caitlin Fitzsimmons of The Sydney Morning Herald praised it as "an engaging read".[12]

Translations

- French: Ce que l'amour m'a appris, lit. 'What Love Taught Me'. Translated by Fabien Thomas. Neuilly-sur-Seine: Michel Lafon. 2018. ISBN 9782749937908.

- Spanish: Libre para volar, lit. 'Free to Fly'. Translated by Julia Fernández. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. 2019. ISBN 9788491815952.

References

- ^ Rowell, Rebecca (1 September 2014). Malala Yousafzai: Education Activist. ABDO. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-61783-897-2. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ Adam B. Ellick (2009). Class Dismissed. The New York Times (documentary). Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ "Pakistani Heroine: How Malala Yousafzai Emerged from Anonymity". Time. 23 October 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ "Young Pakistani Journalist Inspires Fellow Students". Institute of War & Peace Reporting. 15 January 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ^ Peer, Basharat (10 October 2012). "The Girl Who Wanted To Go To School". The New Yorker. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ "'Radio Mullah' sent hit squad after Malala Yousafzai". The Express Tribune. 12 October 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ "Malala Yousafzai becomes youngest-ever Nobel Prize winner". The Express Tribune. 10 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Formats and Editions of I Am Malala" Archived 3 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine WorldCat. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ Clark, Alex (11 November 2018). "Malala's father, Ziauddin Yousafzai: 'I became a person who hates all injustice'". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Freyne, Patrick (17 November 2018). "Malala Yousafzai's father, Ziauddun: 'Let all girls fly'". The Irish Times. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Salmon, Lisa (15 July 2019). "'I didn't clip Malala's wings... I let my daughter be herself'". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ a b Fitzsimmons, Caitlin (23 December 2018). "Malala's message needs to be heard by men and boys". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Turner, Janice (16 November 2018). "'In the beginning, I enjoyed it'". Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Turner, Janice (27 October 2018). "Zia Yousafzai interview: how Malala's father became a feminist in Pakistan". The Times. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Junejo, Shama (23 November 2018). "'Let her fly' — Ziauddin Yousafzai's fight against patriarchy and for equality". Daily Times. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Battle to set her free from patriarchal society: Moving memoir of dad's determination to protect daughter's rights". Cape Times. 31 May 2019. p. 6.

- ^ "Battle to set her free from patriarchal society: Moving memoir of dad's determination to protect daughter's rights". Pretoria News. 6 June 2019. p. 6.

- ^ "When Malala was not impressed by Time magazine ranking". The Hindu. 23 December 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2021.