Great Witcombe Roman Villa

| Great Witcombe Roman Villa | |

|---|---|

The remains of the villa (March 2007) | |

| General information | |

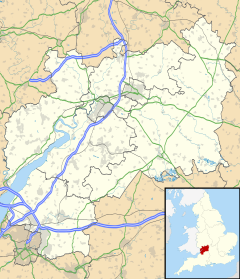

| Location | Gloucestershire grid reference SO899142 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°49′36″N 2°08′51″W / 51.8267°N 2.1474°W |

| Construction started | 1st century |

| Demolished | 5th century |

Great Witcombe Roman Villa was a villa built during the Roman occupation of Britain. It is located on a hillside at Great Witcombe, near Gloucester in the English county of Gloucestershire.[1] It has been scheduled as an ancient monument.[2][3]

Background

[edit]Although a first-century CE date for the Roman villa at Great Witcombe has been suggested,[4] twenty-first century work has suggested that it was first developed between 150 and 200; the villa was enlarged in the late third century or the fourth; additions and alterations were still taking place in the late fourth century; and the villa was probably occupied into the early fifth century.[5]

The villa itself is sited in an unusual location – the unevenness of the terrain, which was riddled with small streams and natural springs, would seem to render it unsuitable for such a large dwelling. It is thought, however, that these springs would have been harnessed into water features in stylised gardens, and that a cult of water nymphs may have been cultivated around this, although this is supposition.[6]

To cope with the difficult terrain, the building itself was constructed on four terraces, cut into the hillside and heavily buttressed, which are still evident on the gallery connecting the two main wings of the house. The architectural design of the villa differs greatly from similar dwellings from the same period, given that the main living quarters were in the large eastern wing, and a long gallery of little function connected this wing with the ‘leisure wing’ where the bath house and temple were located. This layout reflects the evolution of the house over time—the bath house wing was a later expansion—and a consideration of the spatial restrictions of the site.

Remains

[edit]

When the site was first excavated in the 19th century it was reported that parts of the villa were very well preserved. Walls of 6 ft high were documented, some still plastered. The bath house was one of the most complete examples known at the time and several mosaic floors were recorded. Poor conservation techniques and heavy rain have destroyed most of these features.[7]

The site currently consists of the remains of low walls which give a good idea of the general shape of the building. Two parts of the bath house are protected by small sheds, not accessible to the public. Besides its unusual shape, the villa has a few features worth noting, including a bath house and latrine, household shrine and an octagonal room of unknown use.

Latrine

[edit]

The latrine is located near the dressing room of the baths. The main drain on the north side was formed of stone and is still evident today. The fittings were removed in the late 4th century, but debris nearby suggests they were originally made of sandstone. The walls were plastered and coloured white with red stripes and patches of pink. The latrine was accessible via a passageway which contained a mosaic floor. Parts of the plaster fragments of one of the walls still remain.

Bath house area

[edit]

The villa contained at least one substantial bath house, in the north-western wing. This included the latrine, which formed an L-shape around a dressing room (apodyterium). The dressing room led to the cold room (frigidarium) which contained a cold plunge bath and whose mosaic floor, decorated with a design of fish and sea creatures, is still well preserved under a modern protective building. This mosaic suggests an individual treatment of the standard sea animal and fish designs that circulated in copy books. The frigidarium had at least one, possibly two, plunge pools – one of these is now detached from the building owing to landslides.

The apodyterium was also connected via a slype—a small narrow passageway—to the warm room or tepidarium. The remains of under-floor hypocausts, which were filled in during the fourth-century, are still evident today. After the period of Roman Britain various changes occurred which may have included the narrowing of the furnace opening.[8]

Temple/shrine room

[edit]

The shrine room was situated in the north-west wing of the villa. Its only access point seems to have been the staircase leading from rooms on a higher terrace. During the early excavations, the walls of this room were found covered with a coat of stucco painted in panels of different colours. Niches in the north wall that probably accommodated statues and a possible altar base have led the archaeologists, led by Neil Holbrook to suggest that the room had a religious function.[9]

In the middle of the room a small cistern can be found, a common addition to Roman temples. The water in the reservoir was supplied via a drainage system. A small statue and several animal bones were found in the drain, suggesting these were used for offerings.

Octagonal room

[edit]The long gallery connects to a large octagonal room in the middle which was constructed in the 4th century. It is not clear what the exact function of this unusual shaped room was, although it is generally considered to be a reception room.[10] A religious function has also been suggested, but it is more likely that the room simply formed part of an imposing entrance for the building.[11]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Esmonde Cleary, A.; Talbert, R.; Åhlfeldt, J.; Warner, R.; Becker, J.; Gillies, S.; Elliott, T. (19 October 2020). "Places: 79492 (Great Witcombe)". Pleiades. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ "Great Witcombe Romano-British villa". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ "Great Witcombe Roman Villa". Pastscape. Historic England. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ Clifford 1954, p. 25

- ^ Neil Holbrook, 'Great Witcombe Roman Villa, Gloucestershire: Field Surveys of its Fabric and Environs, 1999–2000', Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 121 (2003), 179–200 (p. 183).

- ^ de la Bedoyere 2002, p. 57

- ^ Clifford 1954, p. 9

- ^ "Withington, Gloucestershire Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of the Results" (PDF). Wessex Archaeology. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ Holbrook, Neil (2003). "Great Witcombe Roman Villa, Gloucestershire: field surveys of its fabric and environs, 1999-2000" (PDF). Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. 121: 179–200.

- ^ Ellis, 1995, p. 176

- ^ Todd, 2005, p. 308

References

[edit]- Clifford, E.M. (1954). "The Roman Villa, Witcombe, Gloucestershire", Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 73: 5-69.

- De la Bedoyere, G. (2002). Architecture in Roman Britain, Shire Publications.

- Ellis, SP (1995). "Classical Reception Rooms in Romano-British Houses", Britannia, 26: 163–178.

- Todd, M (2005). "Baths or Baptistries? Holcombe, Lufton and their Analogues", Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 24(3): 307–311.

External links

[edit]- Great Witcombe Roman Villa, English Heritage

- Further images of the site