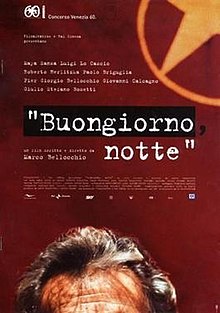

Good Morning, Night

| Good Morning, Night | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Marco Bellocchio |

| Written by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Pasquale Mari |

| Edited by | Francesca Calvelli |

| Music by | Riccardo Giagni |

Release date | 5 September 2003 |

Running time | 106 min |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

Buongiorno, notte (Good Morning, Night) is an Italian film released in 2003 and directed by Marco Bellocchio. The title of the feature film, Good Morning, Night, is taken from a poem by Emily Dickinson.

The plot is freely adapted from the 1988 book The Prisoner by the former Red Brigades member Anna Laura Braghetti, which tells of the 1978 kidnapping of Aldo Moro by the Red Brigades.[1]

Plot

A small group of terrorists of the Red Brigades rent an apartment. They kidnap Aldo Moro, former prime minister of Italy and leader of the Democrazia Cristiana (Christian Democracy) party. Moro writes many letters to politicians, Pope Paul VI, and his family, but the Italian government refuses to negotiate. A female member of the group, played by Maya Sansa, suffers doubts about the plan.

Cast

- Maya Sansa - Chiara

- Luigi Lo Cascio - Mariano

- Roberto Herlitzka - Aldo Moro

- Paolo Briguglia - Enzo

- Pier Giorgio Bellocchio - Ernesto

- Giovanni Calcagno - Primo

- Giulio Bosetti - Pope Paul VI

Production

Bellocchio had already directed a documentary, in 1995, about the Red Brigades and the kidnapping of Aldo Moro. It was entitled Sogni infranti (Broken Dreams).

The title of the film comes from the poem Good morning, midnight by Emily Dickinson,[2] in the 2001 Italian translation by the poet and novelist Nicola Gardini, who first used the form «Buongiorno, notte».[3]

The film was produced by Filmalbatros and Rai Cinema in collaboration with Sky Italia, and distributed in theaters by 01 Distribution. It was recognized as being of national cultural interest by the Directorate General for Cinema of the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities, based on the ministerial resolution of 17 June 2002.

Soundtrack

The original music of the film was composed by Riccardo Giagni. The film's soundtrack also includes compositions by Franz Schubert, Giuseppe Verdi and Jacques Offenbach, as well as two of the most famous songs by Pink Floyd, The Great Gig in the Sky and Shine On You Crazy Diamond - for example, while Chiara sees on television the images of the partisans shot by the Nazis, while reading the Letters of condemned to death of the Italian Resistance (September 8, 1943 - April 25, 1945) - the latter also used in the trailer; The song that the former partisans sing is, instead, Fischia il vento.

Reality and fiction

In addition to the book by Anna Laura Braghetti, the director took inspiration from other sources; for example, the sentence pronounced by the leader of the brigadists, Mariano, to motivate his followers, namely that the imminent killing of Moro "is the highest act of humanity possible in a society divided into classes", is taken directly from a press release on May 10 in the courtroom at the La Marmora barracks in Turin, by the imprisoned founders of the BR, Renato Curcio and Alberto Franceschini: «...This is why we claim that the revolutionary act of justice exercised by the Red Brigades against the criminal Politician Aldo Moro, (...), is the highest act of humanity possible for the communist and revolutionary proletarians, in this class-divided society».[4]

Reception

The film was selected for competition in September 2003 at the 60th Venice International Film Festival, receiving significant critical acclaim, and was also appreciated by the relatives of Aldo Moro.[5] At the same time, the film was released in cinemas, becoming the highest grossing film ever made by Marco Bellocchio at the cinema, with around 4,000,000 euros in Cinetel revenue.

Some former Red Brigades, such as Morucci and Gallinari, said they had seen the film; the former also expressed a moderate appreciation: "His friends denied the authenticity of his letters while some of us, in reading them, we were associating them with those of the condemned to death of the Resistance. This is underlined by the film, and it is really true. It was a shocking thing."[6][7]

Controversy

Although the film was seen as a favorite to win the Golden Lion at the Venice International Film Festival, its only significant award was for the screenplay, arousing much controversy among experts; the director Marco Bellocchio, disappointed, abandoned the event, delegating to the actor Luigi Lo Cascio the task of collecting the prize.[8][9] Following the statements of the jury president Mario Monicelli, which corroborated the motivations that had not convinced the jurors to assign the maximum recognition to the film ("it was impossible to convince foreigners ... this film was not up to its precedent, My Mother's Smile"), Rai Cinema announced in protest that it no longer wanted to participate in the Show:[10] a declaration right after following a meeting between the then president of the Venice Biennale, Franco Bernabè, and the CEO of Rai Cinema Giancarlo Leone.

Awards

- European Film Awards Fripesci Award

- David di Donatello Best Supporting Actor (Roberto Herlitzka)

- Nastro d'Argento Best Actor (Roberto Herlitzka)

- Venice Film Festival Award for "outstanding individual contribution" (Marco Bellocchio)[11]

References

- ^ "RaiLibro - Il sequestro Moro: scavo psicologico e risvolti "affettivi"". 2008-01-11. Archived from the original on 2008-01-11. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- ^ "Corriere della Sera". cinema-tv.corriere.it. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- ^ Ierolli, Giuseppe. "The Complete Poems of (Tutte le poesie di) Emily Dickinson - J401-450". www.emilydickinson.it. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- ^ Aglietta, Adelaide (1979). Diario di una giurata popolare al processo delle Brigate rosse (in Italian) (1st ed.). Milano : Milano libri. pp. 110–111.

- ^ "Repubblica.it/spettacoli_e_cultura: Bellocchio: "Non è un film storico ho raccontato Moro e i terroristi"". www.repubblica.it. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- ^ "Valerio Morucci turbato dieci minuti senza parole - la Repubblica.it". Archivio - la Repubblica.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- ^ SemiColonWeb. "Morucci e Gallinari su "Buongiorno, notte"". news.cinecitta.com. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- ^ "Repubblica.it/spettacoli_e_cultura: Venezia, al russo il Leone d'oro Bellocchio deluso resta a Roma". www.repubblica.it. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- ^ "Il Leone al russo "Il ritorno". Polemiche anche sul palco per il "no" a Bellocchio - Notizie Flash - l'Unità - notizie online lavoro, recensioni, cinema, musica". 2014-12-04. Archived from the original on 2014-12-04. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- ^ "HANNO DETTO". 2014-12-04. Archived from the original on 2014-12-04. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- ^ "Venezia, al russo il Leone d'oro – Bellocchio deluso resta a Roma". La Repubblica (in Italian). 6 September 2003. Retrieved 5 October 2023.