Officers' Association

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (January 2023) |

The Officers’ Association (OA) is a registered charity in the United Kingdom, supporting Former-Officers and their families providing advice and financial assistance, it was founded in February 1920 and incorporated under Royal Charter on 30 June 1921.

It is registered with the Charity Commission under the charity number 201321, as of 17 April 1964.

The OA is the only charity in the UK that represents Officers, their families, and dependents, regardless of their commissioning into the Royal Navy, the Army, or the Royal Air Force. The organisation's purpose is to provide advice and financial assistance to help beneficiaries live independently and overcome severe financial challenges.

The OA also works in conjunction with other charities on a case-by-case basis to ensure the provision of the most suitable support and advice, complementing any available state aid and allowances.

History

The Officers’ Association was formed after the First World War, principally in response to the widely publicised new social phenomenon of ‘the moneyless former-Officer’,[1] categorised as being reduced by circumstances to a state of distress and penury.

Many had given up their education, jobs and careers in order to serve in demanding roles, to which most could not have aspired in the pre-war regular army, only to find themselves demobilised, ‘de-Officered’ and out of work.

They were not eligible for unemployment benefits and training, and were often reduced to begging. The large numbers who had suffered physical wounds and were disabled, as well as those with less outwardly obvious but equally debilitating mental injuries, presented the most challenging cases.

The OA was originally an umbrella organisation, set up to support small, dedicated Officers’ help organisations that had been formed during the war. It then became an organisation that not only administered these organisations but also became a help organisation in its own right.

In February 1920, the OA began dealing with thousands of requests for assistance from former Officers and their families. It also became an official part of the government’s efforts to find employment for disabled and later, able-bodied former Officers.

In July 1921, the OA joined three other ex-services representative organisations, each sharing similar core aims, to form the British Legion, later, the Royal British Legion (RBL). The OA, which by then had been granted its royal charter, retained its identity and maintained its special focus on Officers, becoming the Officers’ Benevolent Department (OBD) of the Legion.

It operated autonomously from its own offices. On amalgamation, the OA handed over its successful fundraising department and a substantial sum of money in order to help the Legion begin operations.

It agreed not to raise funds, (it could still receive funds through donations and legacies) in exchange for a share of the Legion’s annual Poppy Appeal income. This remained its principal source of regular income for the following 100 years.

Initially conceived as being required in the short-term, for a period of around five years, the OA continues to operate today. However, it is no-longer a part of, or dependent on the RBL for funding.

The relatively small, current size of the United Kingdom’s armed services means that there are fewer potential future beneficiaries than there have been historically, especially in the periods following the two World Wars.

There is a continuing need for charitable support for veterans of all ages, and for their families and dependents.

Understanding the circumstances that led to the founding of the OA and later the RBL, the work of the OA as the OBD through the 1920s and 1930s, during and after the Second World War, and into the post-war and Cold War world shows how it was appropriate at the time to give distinct consideration to Officers.

As opposed to serving all veterans as a homogeneous community, the OA’s work from its foundation through to today forms a significant part of the work carried out by the military charity sector. It continues to play an active role in supporting veteran Officers alongside statutory support and benefits that are provided by the UK government.

Provision for Relief of Distress among Naval and Military Veterans and Families on the Eve and Outbreak of the First World War

Before the First World War, the system of state support extended to pensions and retired pay only.

The Royal Patriotic Fund and the Soldiers' and Sailors' Families Association were the largest national charities devoted to the welfare of naval and military dependents at the time.

The Admiralty and the War Office struggled to cope with the demands of managing mobilisation and casualties on an unanticipated and unprecedented scale, these two organisations became central to the administration of government pensions, allowances and grants during the first two years of World War I.

The Royal Patriotic Fund

The Royal Patriotic Fund (RPF) was established by Queen Victoria in the autumn of 1854, at the height of the Crimean War. This war was Britain’s first from which timely and detailed reports, including photographs, of the conduct, conditions and casualties were received and published in the press. This created not only public awareness and concern, but also the desire to help those afflicted by their service. This principle has been applied to all subsequent charitable appeals in support of veterans. The RPF’s purpose was to provide grants to war widows. It was reorganised in 1903 into the Royal Patriotic Fund Corporation.

The Soldiers', Sailors' & Airmen’s Families Association (SSAFA)

Founded in 1885 by Colonel (later Sir) James Gildea as the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Families’ Association. In 1919, after the establishment of the Royal Air Force in 1918, the organisation expanded support to become the Soldiers’, Sailors’ and Airmen’s Families Association SSAFA (The Armed Forces Charity)). Gildea’s first act was to write a letter to The Times to appeal for money and volunteers to help the families left behind by the dispatch to Egypt of the Nile Relief Expedition.

Applying the same principle used by the RPF and adopted by many later successful fundraising campaigns, he made his appeal in the media of the day to generate public interest in and concern for the fate of deployed troops and their dependents.

Provision for Officers’ Widows and Families

At the time of World War I, Officers were expected to have private means to support themselves and their families. War pensions were available to Officers’ widows, however many found that they were not entitled to these pensions despite not having the private means to support themselves. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, almost fifty Officers’ help societies had been established in order to address the lack of support from the government. These were all relatively small endeavours, which were eclipsed in scale by the Prince of Wales’s National Relief Fund. This, like SSAFA, provided a model for future, large-scale, national charities and funds, which aimed to provide relief to disabled veterans and military families in distress.

Officers’ Branch of SSAFA

In 1886, the Officers’ Branch of SSAFA was established. Its aims were to help in the education of Officers’ children and to give small, temporary grants to widows in need. In 1899, Gildea approached some members of the SSAFA Council to set up a home for Officers’ widows and orphan daughters. He launched another appeal in the press and, by publicly presenting a £10 note, made the first donation himself.[2] The Royal Homes for Officers’ Widows and Daughters became an offshoot of SSAFA. Now The Royal Homes, Wimbledon, still managed by SSAFA, accommodates members and former members of all ranks of HM Armed Services.

Officers’ Families Fund

The Officers’ Families Fund (OFF) was founded in 1899 by the Marchioness of Landsdowne, during the Second Boer War, to relieve distress amongst the wives, widows, children and orphans, particularly the daughters, of Officers in the Army. Relief was offered in the form of money, shelter, clothing and education subsidies for children. When she reactivated the OFF in 1914, the Marchioness and her husband lent their London home, Lansdowne House, to serve as its headquarters.[1] The OFF was one of the organisations which later, along with others, came together to form the Officers’ Association.

Lady Grover’s Fund

Lady Grover’s Hospital Fund for Officers’ Families (Lady Grover’s Fund) was established in 1911 by Helen, Lady Grover, wife of General Sir Malcolm Grover, a senior British Indian Army Officer. It was founded in order to address the lack of support for Officers of the Indian Army who were required to cover the costs of hospital and nursing expenses arising from illness and injury suffered by their dependents, who were in most cases, not eligible for military hospital treatment. Lady Grover’s Fund continues to function today as a Friendly Society with membership open to Officers from all three Services, serving anywhere in the world. It has a close working relationship with the Officers’ Association and provides financial grants to its members’ families to help cover costs relating to unexpected illness or injury.

Disabled Officers’ Fund (DOF)

In the autumn of 1915 ‘some ladies in touch with the army’ recognised the need for giving prompt and private help to disabled Officers. They launched what became known as the Disabled Officers’ Fund (DOF). It was based at 12, Dean’s Yard, Westminster and enjoyed support from establishment figures and the patronage of the Their Majesties King George V and Queen Mary, the First Lord of the Admiralty and the Secretary of State for War. The DOF was another of the Officers’ help societies which later came together to form the Officers’ Association.

National Relief Fund

At the outbreak of the war, Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII) made an appeal to the nation to raise a National Relief Fund (NRF) in his name. One of its two principal objectives was to: ‘aid the wives, families and dependents of Soldiers, Sailors, Reservists and Territorials on active service or who had died in the service of their country.’ The Prince of Wales himself became Treasurer and he recruited members of the aristocracy and prominent Members of Parliament onto its various committees. With ‘establishment’ support assured by such patronage, within a week of the announcement, one million pounds had been subscribed to the Fund, Applications to the Fund were co-ordinated by the RPF Corporation and SSAFA.[3] While local RPF funds were not discouraged, and many were raised, the emphasis was on the creation of a single, national fund to be administered centrally. This is another example of a pioneering approach, which influenced military charity fundraising appeals in the years that followed. An early publicity poster for the NRF illustrates this principle, which the original campaigns of SSAFA and the RPF had also profited from, and which later appeals, including that made at the launch of the Officers’ Association, would also benefit from. Namely, that of private, mostly civilian patrons, especially notable people of influence, contributing generously to charitable funds set up to support troops on active service and, by inference, their families at home.

The ‘Officer Problem’ 1914-1918: Wartime Requirement for Additional Officers[4]

Regular Officer Requirements

In 1910, the Army Council had considered the demand for, and supply of, additional Officers in the event of mobilisation. In his report to the Council, the Military Secretary predicted a deficiency of up to 9,698 Regular Army Officers needed to sustain a military campaign: a deficiency of 3,201 for a continental war in Europe and 4,468 for a war in India. In identifying potential sources of these additional Officers, the study proposed, inter alia, that: a large number of Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs) under the age of 35, including those in the Territorial Force (albeit those described as being of ‘superior birth and education’) should be commissioned on mobilisation. It also outlined that lists of suitable NCOs should be kept by regimental Commanding Officers and a special scale of pensions should be provided to enable these Officers to retire at the end of the war or campaign. This was due to the fact that they were unlikely to be able to cover the cost of retaining their commissions during peacetime. The Adjutant-General, Lieutenant-General (later General) Sir Ian Hamilton, had noted that the demands on the upper middle class to continue to produce army and navy Officers, clergymen and Foreign Office staff, were already excessive and that there was a need to ‘tap a new stratum [of society]’. In the pre-war regular army, it was rare for Officers to be

The Regular Army Establishment of Officers

In August 1914, Field Marshal Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, was one of only a few in authority to predict a long war with huge casualties. This would require a greatly expanded army on a scale much greater than that which had been anticipated by the War Office. At the time, the regular army was about 250,000 strong, of which 12,738 were regular (i.e. full-time, career professional) commissioned Officers. Available to supplement the regular Officers, if necessary, were 2,557 in the Special Reserve and 3,202 in the Reserve of Officers. There were also a further 9,563 Officers in the Territorial Force. The necessary expansion Kitchener had envisaged would eventually require the authorities to look much wider than men with prior military experience and to open up to every level of society.

Warrant Officers and Senior NCOs: Impediments to Volunteering for Commissioning

In practice, the greatest impediment to implementing the scheme successfully was how best to persuade experienced, capable soldiers to transfer to a professional domain previously denied to all but a privileged and exceptional few. As Warrant Officers and Senior NCOs they were already enjoying certain privileges and status. On commissioning, they would return to a professionally junior status and level of responsibility. They could expect their presence among monied ‘gentleman Officers’ to be resented by most and, crucially for those with families, there was no obvious financial advantage.

More Favourable Conditions are Created

The eventual solution was a guaranteed pension, paid either as a lump sum on discharge or as an annuity paid over the beneficiary’s lifetime. In January 1914, the War Office announced generous pension provisions for commissioned NCOs which included the option to continue serving after hostilities had ended, and the option to retire with these benefits at any subsequent time. This policy provided an incentive to accept a commission, which was particularly appealing for unmarried senior NCOs anticipating a short War, as most did prior to August 1914. The introduction of these measures paved the way for large-scale commissioning from the ranks as soon as war broke out and as the need became manifest and urgent. The large-scale plan to commission pre-war, regular army NCOs was implemented on 9 September 1914. Army Routine Order 177 provided for ‘the award of retired pay at the rate of eighty pounds per year or a gratuity of one thousand pounds to Officers commissioned from the ranks of the regular army who had completed fifteen years or more in the ranks when commissioned.’ There was a sliding tariff of gratuities for NCOs who had served for less than fifteen years. Experienced Warrant Officers and NCOs who had been discharged to pension were also encouraged to come forward for commissioning. Part of the offer, attractive to many at the time, was the assured opportunity to serve on after the war and the award of a gratuity or a lump sum at the end of their service. They would, however, not receive a regular Officers’ retirement benefits; rather, they would retain their pre-war pensions which would take no account of their commissioned service, regardless of the rank they achieved.

Regular Army Commissions from the Ranks: ‘Ranker Officers’[4]

The First Wartime ‘Ranker Officers’

29 men from the ranks were commissioned in August 1914 and a further 98 in September. On 1 October 187 were commissioned which represented the most commissions granted on a single day than in the ten years preceding the war. Overall, 305 were commissioned in that month. December 1914 (and March 1915) saw 328 such commissions awarded; the highest monthly totals in the war. By July 1915, after just eleven months of war, the 2000 regular commissions anticipated by the War Office in the 1914 plan had been exceeded.

Thousands of Ex-Rankers Awarded Regular Commissions

Between 5 August 1914 and 1 December 1918, official statistics reveal that 6,713 men from the ranks were awarded a regular army commission (41% of the 16,713 regular army commissions awarded during the war), although the actual number was 7,015. Towards the end of the war and afterwards, these men were known colloquially as ‘Ranker Officers.’ Certain Regiments, notably the Foot Guards and Household Cavalry Regiments, took in very few commissioned former NCOs. Between them, the four Regiments of Household Cavalry took only 3 and the 4 Regiments of Foot Guards (each of which fielded several battalions) took only 13 throughout the duration of the war. Infantry regiments of the line were less exclusive, although not necessarily always wholly accommodating towards the individuals. For example, the Royal Fusiliers took 157, The Rifle Brigade 104 and the King’s Royal Rifle Corps 98 ranker Officers during the war. By far the greatest number, 2,643, were commissioned into the Royal Artillery.

Officers Temporarily Commissioned for War Service

The Officers of Kitchener’s ‘New Armies’

Kitchener’s fears were well founded. In the first four months of the war alone, one quarter of the British Expeditionary Force’s pre-war, regular Officers had become casualties. A national recruitment drive was pursued with great rapidity and vigour. Kitchener’s ‘New Army’ of volunteers, later expanded further with the introduction of conscription under the Military Service Act, 1916, which included a new type of volunteer or conscript Officer. Unlike the warrants held by regular Officers, those of New Army Officers, commissioned for the duration of the war, were endorsed with the caveat ‘Temporary’, giving rise to the term ‘Temporary Officer.’ These Officers were usually required to serve in the ranks for a time before being selected to join an Officer Training Battalion, from where they would be commissioned and posted to units. On 7 May 1918, Army Order 159 provided for the granting temporary [war], rather than regular commissions to serving soldiers in the regular army. Recipients of these temporary commissions were to be entitled to the benefits of the Pay Warrant of 1914, which allowed retired pay in lieu of pension on the same rate as those promoted to regular commissions. Anyone serving prior to 7 May 1918 and either commissioned into the Territorial Force or granted a temporary commission was first discharged to pension prior to commissioning and thus had no claim to retired pay. Those commissioned after 7 May 1918 did, in contrast, have the right to retired pay.

Temporary Officers in the Tens of Thousands

A total of 225,316 army commissions were awarded between August 1914 and December 1918. Of these, 212,772 (93%) were either Temporary, Territorial or Special Reserve Commissions. Most of these men would not have been financially secure enough to have been commissioned into the pre-war regular army; nor would most have had the resources available to maintain their positions in the post-war regular army. Colloquially, Officers commissioned for the duration of the war were referred to as ‘Temporary Gentlemen’ or ‘TGs’, an ironic term frequently used both dismissively and pejoratively.

Airing Grievances: Formation of Ex-Services Representative Organisations during the War

Stirrings of Discontent

The formation of the Officers’ Association (OA) in the aftermath of the war was preceded and in many ways, stimulated by the foundation during the war of several significant ex-service representative organisations. The three most significant of which were known generally as The Association, The Federation and The Comrades. Understanding their respective foundations’ motivation, support and significance gives valuable insight into the differences between these organisations and the OA. It also provides an insight to why, after the war, the OA continued and the other organisations gave up their individual identities. SSFA, the RPF Corporation and the Prince of Wales’s NRF existed principally to relieve distress among families and dependents. They were, however, apolitical charities and not openly critical of the government’s failure to provide proper and adequate support. Nor did they actively bring the concerns and grievances of serving, discharged and retired service personnel to the government’s attention. Serving and ex-service personnel were represented, albeit indirectly, only by retired senior Officers on the executive committees of these organisations. From late 1916 onwards, given impetus by the introduction of conscription under the Military Service Act, 1916 and the enormity of the casualties resulting from the Somme campaign, informal and disparate groups of former servicemen began to coalesce into vocal and politically active national representative bodies.

The Association.[5] (National Association of Discharged Sailors and Soldiers (NADSS)

The Trades Council movement had voiced its opposition to the war from its outbreak. In September 1916, the Blackburn and District Trades and Labour Council (Blackburn Trades Council) arranged a meeting with the intention of ‘forming an association of discharged soldiers and sailors who had been wounded or otherwise incapacitated during the war’, for mutual support and to press on government their case for adequate, statutory support. The Blackburn Association’s aim was to: ‘be of material service to men who have been wounded or otherwise incapacitated during the War, by giving them assistance in obtaining employment, pensions, sickness benefit, etc.’ The Blackburn association held its inaugural meeting on 13 September and from then on began to write to other Trades Councils (TCs), urging them to form similar associations. Blackburn TC hosted a meeting of these associations on 31 March 1917, which is acknowledged as the founding of the National Association of Discharged Sailors and Soldiers (NADSS, usually referred to simply as ‘the Association’). Most of the Association’s membership was drawn from the industrial areas of the English north and midlands, central Scotland and South Wales, although branches were established as far apart as Plymouth, Pembroke and Dundee.

The Federation.

On 15 January 1917James Hogge MP, a Scottish radical Liberal Member of Parliament launched the Naval and Military War Pensions and Welfare League (usually referred to simply as ‘the League’). Hogge had been a tireless opponent of the war since 1914 and campaigned on behalf of Naval and Military veterans and families. In his circular to the local and national press Hogge, both informed and prescient, said that his experience had ‘convinced him that it is necessary to organise a new association to deal with the present circumstances and those which will arise more acutely on demobilisation.’[5] The Military Service (Review of Exceptions) Act, 1917, made it possible for men who, under the 1916 Act, had previously been rejected, declared unsuitable for overseas service, or had been discharged from Naval or Military Service, including on account of wounds, to be conscripted or re-conscripted. Reaction to the Review Act was swift and public, including demonstrations by ex-servicemen in London. Hogge, William Pringle, a fellow Scottish Liberal MP, and Mr F.A. Rumsey of the Poplar Discharged Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Club met in April to found what became the National Federation of Discharged and Demobilised Sailors and Soldiers (NFDDSS, usually referred to simply as ‘the Federation’). The London Headquarters of Hogge’s League became the Federation’s Headquarters. Although branches were raised nationwide, the Federation was always principally a London organisation. It espoused the belief that ex-servicemen should not be left to the vagaries of charity, but should be provided with statutory support from the government and should have a say in what that provision would be. Officers, other than those who had risen through the ranks to be commissioned, were barred from membership.

The Comrades.[5]

The idea of a third organisation, less radical and left-leaning than the Association and the Federation, was first mooted in public in a short paragraph in the Daily Mirror of 19 July 1917. In it, Lt Col Sir John Norton Griffiths MP declared that he had ‘formulated a scheme by which those who have fought in the war shall join together for mutual advantage and protection during and after demobilisation.’ Lord Derby, by then the Secretary of State for War, had direct professional and personal interests in countering the increasing political influence now being exerted on government performance and policy by the Association and especially by the Federation. On 1 August, he presided over a conference of interested people at Derby House, his London home, at which a constitution was discussed. A meeting was held in the War Office on 15 August, which became the inaugural committee meeting of the Comrades of the Great War, (usually referred to simply as ‘the Comrades’). Its formation was announced to The Times and other national newspapers on 23 August, in which the signatories, ironically all ‘service’ MPs, albeit from across the political spectrum, stated that it would be ‘wholly non-political and democratic in character.’ The Comrades, which found its support mainly in rural areas and in provincial towns, especially in the southeast and southwest of England, enjoyed support from newspaper proprietors, wealthy benefactors, and senior military Officers. It was also able to operate freely among the troops on the Western Front: service precluded full membership but those serving could be recruited as ‘honorary members’. In contrast to the stance of both the Association and the Federation, the Comrades were not opposed to traditional forms of charitable activity. And, unlike the Federation, it did not exclude or discourage Officers from becoming members. At first, it could not be called a-political or democratic, and its relations with the Association and the Federation were not warm. Despite its first appeal failing to raise funds close to its anticipated target, by late-1918 the Comrades had, nonetheless, become established as the third major, national ex-service representative membership organisation.

Post-War Problems with Retirement Pay and Pensions, Gratuities and Grants

Maladministration Follows Armistice

Following the Armistice in November 1918, the scale and pace of demobilisation were, like those of the mobilisation in the early phases of the war, unprecedented in British history. The effort required, placed demands on the Pensions Ministry, the War Office, the Admiralty and the new Air Ministry. These circumstances conspired to create the impression of maladministration. The consequences of delayed payments led to widespread distress and impoverishment.

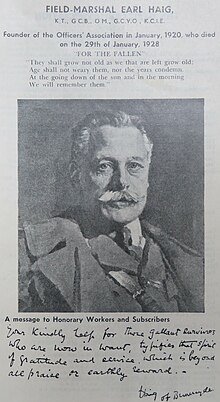

Field Marshal Haig’s Concern

Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig (later Field Marshal Earl Haig), former Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force, had long been interested in the welfare and prospects of ex-servicemen and, in particular, of former-Officers. In this matter, he was well-informed by his wife, Dorothy, who was one of the ‘group of ladies’ who had set up the Disabled Officers’ Fund in 1915. Her own war work had included working at the Blinded Soldiers and Sailors Hostel (known as St Dunstan’s, now the charity Blind Veterans UK). As well as, in the evenings, helping with the cooking at a hut in Victoria Station which served Officers returning from the front. In February 1917, Haig wrote to the Army Council about ‘the state of poverty … to which many of our invalided, wounded Officers are reduced ... which, if allowed to continue, will constitute a scandal of the greatest magnitude’.[5]

Ranker Officers Encouraged to Resign

One consequence of the demobilisation of the Territorial and New Army formations was that ranker and other regular Officers promoted to acting senior command and staff appointments reverted to their substantive rank and were posted back to their parent, regular army regiments. In some cases, Officers who had commanded battalions of 1000 men as Lieutenant Colonels faced the prospect of being reduced to their substantive rank of Lieutenant, a rank at which they would be expected to command a platoon of 30. Not only would this necessarily result in loss of professional status, it would also oblige those affected to serve as subordinates in peacetime to Officers whom they had commanded in war. More significantly for most, it would result in significant reductions in income. In some cases, War Office correspondence used pre-war NCO ranks when referring to ranker officers. For example, a case file note for Lieutenant Colonel J P Hunt CMG, DSO (and Bar), DCM, who had been a pre-war Colour Sergeant and re-enlisted in 1914 at age 41, was commissioned into the Royal Dublin Fusiliers in 1915 and by 1917 was commanding 9th Battalion in France. He was awarded a Bar to his DSO for his actions in command of ‘Hunt’s Force’ in March 1918 and was created CMG in the King’s Birthday Honours List, 1919. The announcement of this award in The London Gazette listed him as ‘Temporary Major (Acting Lieutenant Colonel)’[6] Despite his rank and record, his War Office case file refers to him as ‘Colour Sergeant (Lieutenant Colonel) J P Hunt’ (and shows no decorations).[7]

For many like Hunt, continuing to serve as Officers in a much-reduced peacetime regular army would be unaffordable and their only option was to retire promptly into circumstances, which for too many, were far from favourable.

Select Committee on War Pensions 1919

The issue of the maladministration of pensions and allowances was brought starkly to public notice in July 1919 when Haig gave damning evidence against the government’s efforts to the Select Committee on War Pensions and Allowances chaired by Sir Anderson Barlow (a founder member of The Comrades). In his evidence, Haig claimed that ‘nothing … has been done and the result is that, on discharge, Officers are in many cases left penniless’. His full account of the treatment of disabled former-Officers drew on case studies provided to him by the Disabled Officers’ Fund. It was both detailed and trenchant. In one poignant example, he described the situation of Second-Lieutenant A. Olley, who was in a sanitorium suffering from terminal Tuberculosis. His pension of £145 per year had been abated to £93; his situation summarised as ‘Typical inadequacy of pension in total disability and neglect of Government Departments to inform people of what they are entitled to. ... He also appears to be entitled to children allowance from Special Grants Office, but, of course, was not notified – however, his little boy has just died, probably of starvation so it will save the Government £24 a year.’[8] Haig’s evidence and the committee’s response was reported extensively in the press across the country throughout July 1919, while the Committee was still sitting.

former-Officers Disfavoured by the Select Committee

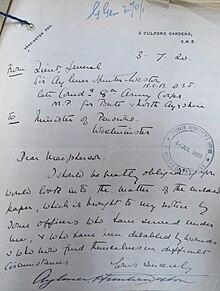

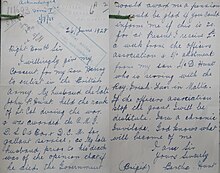

The Committee’s Report made a number of recommendations to the Government. The measures taken had a positive impact on some veterans but a negative impact on others. The issue of Officers’ treatment, especially the iniquities faced by ranker Officers, continued to generate correspondence from aggrieved former-Officers, retired senior Officers and politicians for many years. On 3 July 1920, for example, Lieutenant General Sir Aylmer Hunter-Weston (late Commander 8th Army Corps and MP for Bute and North Ayrshire) wrote to the Pensions Minister,[9] Ian Macpherson, forwarding papers brought to his attention by Officers who had been ‘disabled by wounds and now find themselves in difficulties.’ On 16 July 1920, the Minister for War and Minister for Air, Winston Churchill, also wrote to Macpherson[9] around the matter of retired pay for Officers with wound pensions. He acknowledges that the decision rests entirely with Macpherson but opines that it is also one in which ‘...the War Office can not entirely disinterest itself.’ He goes on to state that ‘... we cannot fail to concern ourselves with the fate of wounded Officers...’ On 8 September 1920, Capt (Brevet Major) C.L. Brereton, Royal Artillery, wrote to the Secretary of State for Pensions,[9] outlining his own situation. He claims that under the new Warrant, he would receive only £50 a year more than were he retiring on grounds of ill-health, despite having lost two limbs, yet while on full pay he was allowed £100 a year compensation for each limb lost. Further, were he not in receipt of a wound pension, he would be allowed an extra allowance for his brevet rank, to which he was not be entitled.

The Geddes Axe Cuts Out More Regular Officers

The proposals put forward in February 1922 by The Geddes Committee on National Expenditure, which aimed at achieving significant reductions in public spending, included the reorganisation and reduction in the size of the regular army. Collectively, the measures were known as ‘The Geddes Axe.’ The proposal saw cuts to the regular army of 50,000 Officers and men, including the disbandment of six Irish infantry regiments brought about by the process that led to the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922. The Royal Warrant of 11 May 1922, insensitively entitled ‘Disposal of Officers on Reduction of Establishment’, was a measure that gave the army powers to institute compulsory retirement (i.e. redundancies) in order to reduce the number of serving regular Officers. A letter of notification gave selected Officers just ten days’ notice of being removed and gazetted. The criteria for selection were vague and included in-house, regimental committees deciding whether someone had ‘no prospect of a military career’. The process of decision-making concerning who should stay and who should go was shaped by the return of pre-war assumptions about the connections between upbringing, education and social class in addition to military competence and prospects as an Officer. The subjectivity and inherent bias in the process clearly disfavoured ranker Officers. It also put out of work regular Officers, not necessarily Great War veterans, who had intended to make the armed services their career. 12,738 regular Officers had been serving when the war began in 1914; there were 12,974 serving by 1924 who, as before the war, were expected to have private means, thus reinforcing the assumption that Officers and their families and dependents needed little or no financial support in the event of death or injury in service and on retirement.

The Persistent Problems faced by Ranker Officers

In 1918, the average pension drawn by the army pensioner ranker Officer (i.e. a pre-war, retired NCO commissioned having volunteered to return to service as an Officer) was £75 a year. This compared with a minimum of £150 a year retired pay granted in the case of a serving regular NCO who had been given a regular commission. The continuous public debate regarding ranker Officer pension arrangements prompted a review by a committee set up by the House of Commons in 1924. The restoration of full Officers’ pensions to those Royal Marines who had taken regular army commissions, having been granted full pension rights in retrospect by the Royal Navy, worsened the feelings of inequity. The Committee finally recommended no change. In July 1929, the Secretary of State for War advised the House that he saw no grounds for re-opening the situation of army pensioned ranker Officers so long after the war. The lobbying by ex-rankers and their widows, continued throughout the interwar period and the matter was still being discussed in parliament in the 1930s, by which time many of the men concerned were in their early sixties.[10][11][12]

Officers Out of Work

Numerous contemporary accounts bear witness to the impoverished state to which many former-Officers were reduced after demobilisation. While entitled to more generous gratuities than other ranks, former Officers did not get the ‘Out of Work Donation’ which provided, albeit for a limited period, financial support to those discharged from the ranks. The penalties for fraudulent claims were severe, as can be seen in a publicity poster from the time. Many of these ineligible former Officers would not have been commissioned but for the exigencies of generating very large numbers of temporary Officers and would, had they served under other circumstances, been in the ranks and therefore eligible for the Donation. An illustration of this class consciousness among ranker Officers can be seen through a letter to the Secretary of State for War[13] on 14 August 1919, in which Captain Thomas Wadner, King’s Royal Rifle Corps, was enquiring as to the progress of his delayed application to resign his commission. Wadner was a ranker Officer who had enlisted in 1904 and been commissioned in August 1914 (incidentally, on the same day as his brother), he has been wounded while leading his Platoon in action near Ypres in November 1914 and captured and held a Prisoner of War in Germany until January 1919. He describes the reason for his resignation as him having family problems and wanting to start in business ‘ ... in my own class of life...’ The ranks such men as Wadner achieved, and the roles and responsibilities incumbent upon them in the positions to which they rose, may have given some of them over-inflated expectations in terms of post-war, civilian status, employment and salary. Many found in practice that their military service did not necessarily make them competent to set up and run successful civilian businesses, nor did it help many of them find civilian employment, or even to return to their old jobs.[14] One ex-service journal which gave special attention to ‘the ex-Officer problem’ in the period 1918-20 referred, in its final issue[15] to: ‘former-Officers who ... are turning their hands to many things. Brigadier-Generals are acting as company cooks in the Royal Irish Constabulary. Colonels are hawking vegetables. Majors are trading in proprietary goods. Captains are renovating derelict prams. And subalterns are seeking anything which will keep them from having to fall back on charity or beg in the streets.’

The Founding of the Officers’ Association

An Umbrella Organisation for Existing Officers’ Help Charities

On 26 August 1919, Haig chaired a meeting of organisations dedicated to helping former-Officers in distress with the intention of reporting on their combined efforts and making recommendations. The committee’s report recognised that their work had saved ‘many hundreds of Officers and their dependents … from suffering and hardship’, but also that better co-ordination was needed to reduce overlapping, to save expense and to promote efficiency, as ‘great hardship is now inflicted upon many claimants for help, by the uncertainty as to which particular organisation they should apply’. It recommended that they divide themselves into four groups, covering Housing, Employment, Families, and Unfit Officers, each supervised by a ‘Group Committee’, under one overall ‘Central Committee of Control’. It recommended that: ‘each Society should continue to manage its own affairs as at present … under its present name,’ but suggested that it was ‘desirable to have a brief title for the whole organisation’. In October, Haig was able to declare that if the recommendations met with general approval, he would take steps at once to form an Association.[16]

Coalescence of the Officers’ Help Community

On 25 November 1919, Haig chaired another meeting of these organisations at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), London. Those represented were:[17] Kitchener House Club for Wounded Officers; Disabled Officers’ Fund; Tanks Association; Queen Alexandra’s Relief Fund; Housing Association for Officers’ Families; The Imperial Association; SSAFA; Disabled Officers’ Home and Club; Disabled Officers’ Home; Ex-Services Association; King’s Fund; former-Officers’ Club; RAF Memorial Fund; Officers’ Families Fund; Sam Browne Circle; United Services Co-Operative Poultry Farm; Ex-Services Welfare Society; Royal Military Benevolent Fund; Women’s Auxiliary Force; Imperial Ex-Services Association; Air Force Memorial Fund; Officers’ Families Industries; Disabled Officers’ Society; Lloyds Patriotic Fund; Nation’s Fund for Nurses; Disabled Officers’ Residential Club; The Village Centres Council; British Emergency Relief of Pennsylvania (sic); former-Officers’ Employment Bureau; Housing Association; former-Officers’ Farming Association and, from interested Government Departments, the ‘Officers’ Friend’ Department, Ministry of Pensions and the Ministry of Labour (Appointments Branch). The status of those in attendance is indicative of the level of engagement in these associations and the interest in co-operation. In addition to Haig, among the 45 people present were two Generals, two Lieutenant-Generals, three Major-Generals, one Brigadier-General, and among the civilians one Knight and one Dame. It is important to note that there were no representatives of Naval organisations present.

An Ambitious Association

The record of proceedings is informative, particularly with respect to the anticipated patronage to which the proposed Association aspired. The representative of the Officers’ Families Fund, which had received considerable support from the associations principally concerned with Naval Officers, stated that his organisation could not join the Officers’ Association until assured that the Association would also deal with naval Officers and dependents. Haig stated that he was ‘only too anxious’ to include the Navy. When questioned on the composition of the Central Committee, again with reference to Naval representation, Haig stated that it should include ‘as many influential gentlemen as possible.’ On the matter of the funds held by individual organisations, he made it clear that it was not desired to take away the funds from any particular organisation; all that was wanted was unity among all the organisations. Haig went on to describe the individuals whose services he had been able to secure for the roles of Chairman of the Central Committee; Secretary and Financial Advisor and chairmen of groups dealing with Employment, Housing; Families and Disabled Officers. After some discussion, the size and composition of the Central Committee was amended in order to assure permanent Naval and Air Force representation. Following a somewhat parochial discussion of single service representation, Mr H.G. Tetley (Disabled Officers’ Residential Club) stated that what was wanted was ‘to get as many monied and influential gentlemen as possible to help’, regardless of their own Service background (if any). This was reinforced in his overview by Sir Arthur Lawley, the nominated Chairman of the Central Committee, in which he stated that: ‘the Committee should include men of influence of all sorts and conditions, representatives of the Army, Navy and prominent men of the City of London.’ And, later, that: ‘We are hoping to have at our disposal substantial funds.’ [17]

Haig Confirms Formation of The Officers’ Association

Haig forwarded the record of proceedings to the Secretary of State for War under his own signature, signed, as a Service Chief, in green ink, according to military custom.[17] He stated that all the organisations represented had, ‘... agreed to join the “Officers Association”’. He described the chief objects of this Association as: ‘to coordinate the work of the various Societies, to prevent overlapping and thus avoid any waste of money, and to co-operate with the Government departments whose efforts are directed towards the assistance of those Officers who have suffered as a result of the Great War.’ In January 1920, Haig wrote to thirty-four senior figures inviting them to join what was now called ‘the Central Council of the Officers’ Association’ and to attend its public launch at the end of the month. That was also the last month of his tenure as Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces, a post that was to be abolished on his retirement. The end of his career in the British Army allowed him to devote his remaining years to the welfare of ex-soldiers. Indeed, Haig had refused a peerage at the end of the war as a means of applying pressure on the government to address the issue of the welfare of demobilised servicemen and women and was only created 1st Earl Haig (also 1st Viscount Dawick and 1st Baron Haig of Bemersyde) on 29 September 1919, almost one year after the Armistice and well after his retirement.

Haig’s Aim

Haig’s ultimate aim was, however, not simply to create a unified organisation to provide benevolence to former-Officers and their families. His vision was a single, unified ‘Great Association’ that would support all who had served, regardless of former military rank and current position. He expressed the hope that the meeting may have been the beginning of the ‘former-Officers’ branch’ of this Association. From the evidence assessed, it was estimated that the sum required to relieve distress amongst former-Officers and their dependents might require up to half a million pounds in the first year alone, and that a fund of three to four million pounds would be required to meet the Association’s objects.[18]

Official Public Announcement of the OA

On 30 January 1920, Sir Edward Cooper, Lord Mayor of London, held a dinner in the Mansion House at the request of Earl Haig, Admiral of the Fleet Earl Beattie and Air Marshal Sir Hugh Trenchard (Later Marshal of the Royal Air Force, Viscount Trenchard). At this event, Haig launched an appeal for what formally became The Officers’ Association.[18] His speech highlighted ‘20,000 former-Officers [who] were out of employment through no fault of their own’ and ‘33,000 … incapacitated who were trying to eke out an existence in many cases with a wife and children on an average pension of £70 a year’. He added that while they were presently only assisting former-Officers, they intended ‘to lend a helping hand to the men as well’. The OA’s first Secretary was Major-General Sir Harold Ruggles-Brise, who had been Haig’s Military Secretary in France, and who had represented the Disabled Officers’ Fund at the meetings in November 1919. The Association’s first task was a major public appeal for funds to provide Lawley’s anticipated ‘substantial funds.’

The Officers’ Association: Launch, Influence and Impact

Haig Personifies the OA

Following the launch of the OA in January 1920, The Daily Graphic, a popular tabloid of the time, featured a full-page portrait of Haig on its cover and on the next page, carried ‘Earl Haig’s Message to the Nation’.[19] This overt, striking public appeal was substantially different from any previous newspaper coverage of the Association, Federation or Comrades, none of which were charities and all of which had eschewed public fundraising. Positive coverage, featuring Haig’s leading role, typified the way the launch of the Officers’ Association was reported in almost every national, regional and local newspaper in the UK. It was also supported throughout the year in the press, in music halls and in cinemas. The launch and subsequent publicity included moving examples of the poor conditions that some former-Officers were in, citing Haig’s figures of tens of thousands incapable of work or unemployed and ineligible to claim the ‘Out of Work Donation’ available to ex-rankers. Items such as that urging the public to ‘Honour Your Bond’[20] challenged openly and starkly the long-held public mis-perception that former-Officers had no need of financial support. Haig was keen to dispel any lingering belief that they had private wealth, noting that ‘the majority of the former-Officers now in need of assistance obtained their commissions from the ranks, making it clear that they were not from the monied middle classes and implying that in so doing, they had lost any entitlement to ex-rankers’ benefits.

Patronage, Profile and Influence

Throughout 1920, the OA maintained a high profile through fundraising events, often with royal patronage (the example most often quoted is a garden party in the Botanic Gardens, attended by the King and Queen), and through sympathetic newspaper editorials. The result of all the sustained appeals to the public was that in 1920, the OA raised over one million pounds from bodies such as Lloyds, the Prince of Wales’s National Relief Fund and the Red Cross. £637,000 came from the public, of which £288,000 was subscribed by four large companies.[21] This was in contrast to the dwindling fortunes of the other three main ex-service organisations. The Association and the Federation had from the start vigorously opposed ‘the cold hand of charity’, believing that ex-service men, women and dependents were owed full state support and that charities should not provide where there was a clear failure of government to fulfil its obligations. The Comrades had adopted a different stance, but their initial appeal in 1917 had failed to generate meaningful funds. They were about to repeat that appeal in early 1920 but, as the Comrades conceded, the OA launch and attendant widespread publicity ‘cut the ground from under their feet’.

Differences Between the OA and the Association, the Federation and the Comrades

An important feature of the OA, not necessarily made clear in most historical accounts, is that it was substantially different from the Association, the Federation and the Comrades, which were membership organisations run by those who benefited from their work. The OA was not primarily a membership organisation; rather, it was conceived initially as an umbrella group for numerous small Officers’ help societies. It quickly became more like a traditional charity run by prominent socialites and persons of prominence who raised money from the public and institutions, and dispensed support to needy individuals through its constituent societies. It did have individual members, but these included ‘all who are interested or concerned in the ex-Officer problem’. They were not members in the sense of the other three groups, which were primarily collectives of men and women who had served in the British armed forces, or their widows.

February 1920: The OA Starts Work

The OA began its work in February 1920 from a rented office in Grosvenor Place, Victoria, with a small staff of around six people. Shortly after, the Duke of Westminster (who was himself a decorated veteran of the war) offered accommodation at 48, Grosvenor Square at a peppercorn rent. In order to receive support, membership of the OA was not necessary but it was encouraged. In the first few months, 10,000 joined; membership continued to rise and eventually reached 26,000. Significant as this number was, it represented only around 10% of Officers who had held a commission during the war. Although membership of the Association did not necessitate membership of a branch, within a year there were one hundred branches, including two in Scotland, one in Wales and twenty-five overseas. In 1925, again courtesy of the continued generosity of the Duke of Westminster, the OA moved to offices at 8 Eaton Square.

The OA’s Success and its Influence on the Other Organisations

The public profile of the OA and its successful fund-raising did not only benefit former-Officers, it also prompted the other organisations, the Federation in particular, to reassess their aversion to charity. Previously, the Federation had set much store in building the strongest possible case for better pensions, more training, improved allowances, proper housing, and more. After many delays, the Federation’s leaders were finally able to present their members’ case in detail to the Prime Minister and senior Ministers in February 1920. Prime Minister David Lloyd George, in responding to the matter of the government being unwilling to raise the rate of pre-war pensions stated: ‘I am not going to tell you it is not fair; I am not going to tell you it is not just, and I am certainly not going to tell you that if we could afford it we would not do it. We certainly should, but we cannot.’[21] The response was the same to all the matters the Federation raised that required substantial public expenditure. This rejection of the issues fundamental to the Federation’s raison d’être came barely a week after the high-profile launch of the Officers’ Association and its well-publicised appeal. The success of the OA’s appeal had demonstrated that charitable funds might become part of future support for its members, alongside government allowances. From this point on, the Federation began to give serious consideration to amalgamation with the other ex-service organisations.

Royal Charter

Given the support it had garnered, the OA understood that a royal charter would not only assure prestigious royal patronage but would also safeguard the funds subscribed specifically for Officers as well as the future identity and integrity of the Association itself. On 10 November 1920, the Association’s Grand Council met to agree a draft petition and the proposed charter. The ‘humble petition of the Officers’ Association’ was submitted to ‘the King’s Most Excellent Majesty in Council’ on 16 February 1921, in which the petitioner showed that: ‘Your Majesty has graciously consented to be patron of the Association.’ Its objects were five-fold: ‘(a) Generally to promote the welfare of all those who have at any time held a Commission in Your Majesty’s Naval Military or Air Forces; (b) To aid the wives and aid in assisting and maintaining and educating the children of Officers who were killed in the late war; (c) To assist Officers who are totally or partially disabled and their families and dependents; (d) To assist and where possible to find employment for other Officers in distress and (e) To co-operate with and co-ordinate the activities of other societies who have like objects. The petition concludes with the statement that: ‘Your petitioner believes that the granting of the proposed charter will enable the objects with which your Petitioner was founded to be more effectually realised, by giving to the corporate body thus created a higher form of constitution and conferring upon it additional dignity and influence.’ In the draft charter enclosed with the petition, Article V states: ‘We reserve unto Ourself Our Heirs and Successors the right to be Patron of the Association and to nominate and appoint the Vice Patrons the Presidents and (subject to the preceding Article) the Vice Presidents thereof in such a manner that our Naval Military and Air Forces respectively shall be represented in such offices.’[22] Crucially, it contained no provision for voluntary surrender of the charter by the Association which would, perforce, require an Act of Parliament. The royal charter was granted to the OA on 30 June 1921. The granting of the charter is, arguably, the principal reason for the continued existence of the Officers’ Association in its own right over a century after it was founded.

Towards Amalgamation and Unity: The British Legion [23]

Unity Proposals

Although the founding principles of the Association, the Federation and the Comrades were based on strength through unity, the desirability of actually uniting the organisations themselves was first espoused publicly, by James Hogge, only in 1918. In May, he wrote to the Manchester Guardian, saying: ‘It is vital that discharged men should concentrate their energy’. In June, he announced his intention to form an ‘amalgamated union of discharged and demobilised men.’ On 28 and 29 July 1918, a conference of 200 Association, Federation and Comrades delegates met at the London Palladium. On 30 July, a meeting of members of the three separate Executive Committees was held in the Central Hall, Westminster, under the chairmanship of General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien (who had been removed from command of the 2nd Army in April 1915 for baulking at orders which, in his view, would have led to unacceptable and avoidable casualties). Speeches favourable to amalgamation were made and the discussion relating to the contentious issue of Officer membership was set aside for later resolution.

The United Services Fund – a Unifying Influence

A government consultative committee, where the three services were represented, was convened at Whitehall in October 1918, chaired by General Sir Julian Byng (later Field Marshal Viscount Byng). It was to consider the formation of a league of ex-servicemen and to decide on the administration of the accumulated £8 million in Army and Air Force canteen profits which, it was decided, should be returned in some way to the men who had spent their money in those canteens. Haig was represented on this committee by his Military Secretary (General Sir Harold Ruggles-Brise, later the first Secretary of the OA). Winston Churchill, as War Secretary, answering questions from MPs about the new fund, stressed that the ex-soldiers had strongly expressed their desire to be ‘free from War Office control altogether’, and accordingly the United Services Fund (USF) was to become ‘a body administered under Royal Charter.’[24][25]

Formation of the OA adds Impetus

At the end of 1918, both the Association and the Federation severed their party-political links and became more conservative in outlook, and thereby more closely aligned with the Comrades. In May 1919, the Federation decided to permit Officers to join and, in the face of widespread and increasing hardship across the country, abandoned its stance against voluntary and charitable support. The most significant failed attempt at unity was the Empire Services League, first proposed in 1918 by General Sir Ian Hamilton (the pre-war Adjutant General who had been a proponent of commissioning from the ranks and had supported the proposal to grant appropriate pension rights to ‘ranker Officers’). The initiative appears to have been scuppered by politically motivated interference and indifference. The formation in 1919 of the Officers’ Association as the fourth major, national ex-services organisation contributed, along with other factors, in driving all four organisations to eventual amalgamation, which had long been Haig’s aspiration.

The Welsh Legion

By February 1920, the Comrades’ Grand Council had decided to support the amalgamation initiative which was endorsed by the organisation’s annual conference in May. One of the most important, albeit largely unacknowledged, events in the unification process was when Welsh branches of the Federation and the Comrades set a precedent by amalgamating first as ‘The Welsh National Federation of Comrades’ at the end of 1919, and then re-forming as ‘The Welsh Legion of Ex-Service Men’ in May 1920. In August, Haig accepted the invitation to become its President. This amalgamation was significant not only because the national bodies were beginning to accept amalgamation as an inevitability, but also for the use of the name ‘Legion’ before the later agreement of that name at the founding of the British Legion. Haig’s acceptance of the ‘Welsh Legion’ presidency was equally significant, as he had had previously refused offers of senior posts in any of the three separate organisations until they had agreed to unite to create his single ‘great organisation.’[26]

Unity is Discussed and Agreed

In July 1920, facing dwindling membership and reserves, The Federation executive invited representatives of the Association, the Comrades and the OA to a joint conference. Not only were all four facing problems, but they were all now publicly committed to the process; factors which meant that formation of the unified organisation progressed quickly thereafter. A Provisional Unity Committee was formed and the first ‘Unity Conference’ was held at RUSI on 7 August 1920. A sub-committee met on 21 August to establish the principles of a constitution. It required only two further meetings to produce the first draft. The second unity conference on 18 September hammered out what was essentially the draft to be presented for approval and acceptance. The Federation held a ‘Special Conference’ in Leicester on 13 and 14 November, which began with a procession through the city, led by the Mayor and Deputy Mayor, who were joined by Earl Haig, and the band of the Federation’s Leicester branch. In the evening, there was a ‘Grand Dinner’ with Haig as ‘honoured guest’.

Hard Times

The Officers’ Association had the issue of damaging publicity to address around this time. There was a spate of newspaper articles claiming that impoverished former-Officers playing the barrel-organ for money, perhaps among the most iconic images of Officers in impoverished circumstances, were actually making much more than if they had taken the jobs that had been offered to them. It started in November 1920, with the Daily Mail reporting a case in Manchester where two former-Officers were charged with ‘obstructing traffic … by playing a barrel organ’ while wearing black masks. People ‘sympathised so much that £5 was given in two hours’. Such cases prompted the Officers’ Association to investigate, at first to offer assistance, but when job offers were refused because they could not ‘offer them a job at which they can earn as much money’, they reported their suspicions to Scotland Yard.[27]

Suspicions Fail to Prevent Amalgamation

Their collective problems simply added to the pressure on the four organisations to complete the amalgamation. Further impetus came from the deteriorating economy. Unemployment exceeded 500,000 in November 1920, and almost doubled over the next two months (figures which are judged to be under-estimates). Ex-servicemen accounted for half or more of this number. This increased the pressure on the groups’ relief funds, and their employment and other support services. In November 1920, the Daily Herald acquired a cache of confidential OA documents which, it claimed, showed how the OA intended to ‘run’ any amalgamated organisation and how the OA gained unfair advantage from its favoured ‘establishment’ status. It seems that while these stories may have confirmed some people’s prejudices and others’ suspicions about the Officers’ intentions, prejudices which persisted for decades, they were not damaging enough to prevent unification.

The British Legion

By the time of the unity conference held at Queen’s Hall in London on 14 and 15 May 1921, the most contentious issues had been resolved. The conference considered and amended the constitution and unanimously adopted the name ‘British Legion.’ The Prince of Wales became Patron and Haig was elected President. On the morning of Sunday 15 May 1921, the conference delegates trooped from Queen’s Hall to the Cenotaph, where four men laid a laurel wreath which contained the emblems of the four separate organisations in a symbolic gesture confirming the amalgamation, before marching on to the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey. The British Legion was formally established on 1 July 1921. Former-Officers who had been subscribers to the OA were now encouraged to join the Legion on the same basis as other ranks. From 1925, when it was granted its royal charter, the organisation became the Royal British Legion. The amalgamation, and the four amalgamating organisations, were acknowledged publicly on the occasion of the Legion’s 60th anniversary in 1981 on one of the commemorative stamp envelope designs, the proceeds of which went towards that year’s Poppy Appeal.

The OA Becomes the Officers’ Benevolent Department of the British Legion [28]

The OA Retains its Identity within the Legion

The OA surrendered its highly successful appeals department to the Legion and was able to give the fledgling organisation £10,000 in cash, a quarter of which had been collected from subscription fees, the remainder was a gift. The OA’s public appeals funds were restricted by law to the provision of benevolence to former-Officers. No figures have been found for the finances of the Association and the Federation, however they were unable to contribute any substantial sums upon amalgamation. Rather than being absorbed into the Legion, as the Association, Federation and Comrades had been, the OA retained a distinct identity and became known as the Officers’ Benevolent Department (OBD) of the British Legion. It used the title Officers’ Association principally in legal and financial documents and written correspondence, where the Legion link was also made clear. The style of the earliest official correspondence gave the British Legion’s name precedence by placing it in superposition above that of the Officers’ Association.

Financial Accommodation

The OA had been preparing to petition for its royal charter while concurrently engaged in amalgamation negotiations with many Legion members. Consequently, relations were not always cordial. It was felt that a separate department for Officers perpetuated the old, pre-war class and rank distinctions and maintained assumptions about the social position and presumed ‘better’ entitlements due to former-Officers.

Structure and Activities of the OBD

The OA used a centralised structure of paid officials based in London, unlike the decentralised voluntary system adopted by the Legion. The first OA staff branch dealt with all applications for business grants, loans, and training; the second operated as an employment bureau and processed applications from Officers for relief. The ‘Families Branch’ was concerned with distress arising out of family circumstances for wives, widows, orphans, and dependents. A disabled Officer or an Officer’s widow could obtain assistance to buy or maintain a home. Advice was given on pensions and gratuities as well as free legal and financial advice. At the inception of the Legion, the OA had been by far the wealthier of the partners and, significantly, the OA had handed over its appeals branch when it merged with the Legion. The reciprocal part of this arrangement was the OA (OBD) received five percent of the net proceeds of the Legion’s public appeals and one third of all general donations and legacies. The funding of the OA by the [Royal] British Legion continued until its cessation in 2023.

The Officers’ Association at Work in the 1920s

Officers in Distress

During the 1920s, many former-Officers were not in a position to provide any forms of assistance to less fortunate former-servicemen, as might have been expected of them according to pre-war stereotypes. This was because they themselves were in similarly straitened circumstances. In 1921, the OA (as the OBD of the British Legion) assisted 24,221 cases of Officers and their families in distress (twice the number helped in 1920), having actually received 50,500 requests for help. Thus, in its first year of proper operations, the OA provided some form of assistance to the equivalent number of Officers as had been on the strength in the pre-war regular army. The Disablement Branch handled the most cases, closely followed by the Families Branch. Assistance was rendered not only in terms of grants for medical bills and to cover rent arrears but also the distribution of donated clothing.

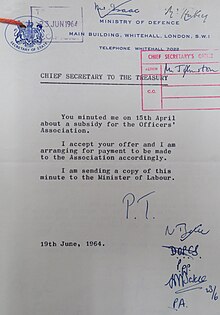

Finding Employment

The Employment and Relief Branch of the British Legion originally ran an employment bureau. Its work was taken over by the Appointments Branch of the Ministry of Labour in 1921 and the OA retained the task of finding work for disabled former-Officers. In the Legion’s 1921 annual report it was stated that: ‘there can be little doubt but that if employment could be found in an adequate degree, the calls upon the Department would be more than halved.’ In 1925, at the request of the Ministry of Labour, and accompanied by a grant of £10,000, the OA took on the placing of able-bodied former-Officers.[29]

The branch was staffed mostly by volunteer former Officers and operated from offices at 4, Clement’s Inn, Strand. This office remained open until 1932, when its work was transferred to the OA Headquarters offices. The OA’s philosophy was to get unemployed former-Officers into work in order to enable them, by their own endeavours, to thrive without recourse to seeking further relief.

‘Work, not Charity.’

It had long been clear, recognised years earlier by Gildea in SSFA’s founding principles, that what unemployed and distressed former-Officers wanted was work. This would allow them to support themselves and their families and to not rely on charity or other forms of welfare. This is illustrated clearly in the correspondence of ex-Captain William Aldworth DSO, a Ranker Officer who had enlisted in 1896, served in South Africa and was commissioned from the ranks in November 1914, before retiring in 1920 with a gratuity (but no pension). In 1921, he submitted an application for a reward for both distinguished and meritorious service under Article 655b of the Royal Warrant for Pay. He describes being wounded in May 1915 and on recovery being sent to Gallipoli and being returned from Alexandria to England for surgery for a debilitating stomach complaint later attributed to exposure. Advised that he would eventually ‘be himself again’, he volunteered to return to action and was sent to France in May 1917. He was ‘brought in from the front line to Battalion HQ absolutely done up’ but ‘struggled on until the end.’ He returned to England as an acting Major, commanding a cadre battalion of his Regiment. After the war, on the eve of being deployed to Malta, he was put before a medical board which declared him unfit. He was ‘forced onto half-pay,’ which he describes as his ‘downfall.’ Like many Ranker Officers in the immediate post-war years, he felt compelled by adverse financial circumstances, compounded by service-related ill health, to retire. In his case, in order to get the gratuity which would enable him to purchase a house to make a home for his wife and family. He was ‘fortunate in securing a sedentary situation, being by now perfectly useless for anything else.’ He had been in contact with the Ministry of Pensions which had decided to award him £20. The grievances felt by many ex-servicemen, especially Ranker Officers, can be understood in light of the cold, perfunctory reply to his reward application from the Military Secretary’s office. It states simply: ‘I am to inform you that as there are such a large number of senior Officers with stronger claims who have not yet been awarded, no good purpose would be served by registering your name as a candidate for the award you refer to.’ Some years later, on 7 September 1927, Aldworth made a personal appeal for assistance to the Military Secretary. He started by saying that his ‘wife and five young children are not having sufficient food’, that they have been and are being ‘supported by friends and relatives’. He described having taken his gratuity, by now gone having been ‘let down by foolishness and inexperience’, and having no pension. Tellingly, he does not play on his poor health, clearly attributable to wounds and the physical rigours of active service, nor on his status as a decorated veteran former-Officer. Rather, he states explicitly: ‘I do not want charity if it can be avoided. All I want is a job of work so that I can support my family.’ He wrote again on 28 August, this time to the Secretary of State for War, stating ‘I do not want charity. I am not eligible for any dole, nor do I want it. What I want is work.’[30]

The OA’s Employment Branch

A Business Branch was set up by the OA to provide loans to help start commercial enterprises. These were made interest-free and with easy repayment terms. It seemed to be a matter of honour that beneficiaries repaid these loans which, in many cases, proved to be life-changing. In gratitude, one beneficiary wrote, offering: ‘You were courageous enough to advance me the cash to start my business when you could scarcely have known whether it would be a success or not,’; another ‘a new lease of life when I was down and out’ and another ‘the day I walked into 48 Grosvenor Square I was in rags and hungry. Now I am faced with much better fortune’. Assistance in the form of business grants, as well as clothing to enable candidates to present themselves favourably at interview; travel to interviews and training was paid for; hostel accommodation was provided for those undergoing training and, for emigrants, the cost of passage overseas was met.

Valuable and Valued Advice

Of those interviewed, only around 10% joined the register. 27,000 called at Clement’s Inn in the first year; of these, 8,000 were interviewed and 1,000 were placed. The strong inference was that the OA’s Employment Branch provided not only a job placement service but somewhere for disabled and distressed former-Officers to meet people who had shared experiences, who were like-minded and who might understand and be sympathetic to their situation and plight. At a time when mental health and combat trauma were not well recognised or understood and for which limited provision or treatment was available, and when so many people were afflicted and sympathy was in short supply, the Branch fulfilled its intended purpose as well as providing a vital, if unintended and largely unrecognised social service.

Rotherfield Court Neurasthenic (‘Shell Shock’) Hospital

Of those former-Officers known to the OA, one third were suffering from neurological conditions, including ‘shell shock,’ described at the time under the umbrella term neurasthenia. In 1920, Mr Henry Tetley, the Chairman of Courtaulds, gave the OA the freehold of Rotherfield Court, near Henley-on-Thames (now the Rotherfield site of The Henley College), which he had established as the Disabled Officers’ Residential Club (he had attended Haig’s unity conference on 25 November 1919). The OA offered the house rent-free to the Ministry of Pensions in order to provide a neurasthenic hospital for Officers. A Ministry survey and cost estimate dated November 1920, describes Rotherfield Court as comprising a mansion house, two gate lodges, stables and outbuildings set in 8 acres of grounds. Having already been fitted out and equipped to a high standard, it could accommodate 51 residents in thirteen single, sixteen double and two triple bedrooms, and included on-site accommodation for staff. Public facilities included a 60-seat dining room, a lounge in the entrance hall (complete with a pipe organ), a billiard room, a writing or smoking room and a sitting room. In March 1921, the Treasury accepted the Pensions Ministry’s recommendations and approved the acquisition under the terms offered by the OA. Rotherfield Court took in around one hundred in-patients each year for an average 6-month stay, during which they received physical and psychological therapy. The hospital operated until 1926, after which the Ministry made other arrangements. With the consent of Mr Tetley’s widow, the OA then sold the house and grounds, the proceeds of which were put towards providing educational scholarships.

Ten Years on from the end of World War I

In 1928, not long before his death, Haig had set up a committee to determine the OA’s future financial needs. Faced with continuing economic recession, demand for support had remained high. Although by then the war had been over for ten years, the OA was still dealing with 1,000 cases each week. The employment offices at Clement’s Inn were still receiving 20,000 callers a year, of whom 4,000 were interviewed and half given letters of introduction. The bureau itself found work for around 600 former-Officers each year. The committee estimated that at then-current rates, the organisation’s capital would be exhausted within five years unless boosted by grants. This was presented a challenge because, amongst other things, commitments had been given to providing educational grants up to 1938, with the peak commitment in the years 1931-32. By which time, underwriting this issue alone would require around £30,000 per year. It was, nonetheless, considered that this activity was ‘the finest of all war memorials,’ and Haig insisted that every effort be made to ensure that the commitments made would be honoured.

Disabled Officers’ Home and Club

The Disabled Officers’ Home and Club at 46, Westbourne Terrace, Hyde Park, had been opened in 1916 by Miss Phyllis Holman as a family memorial to those Officers killed in the war. Miss Holman had been present at Haig’s unity meeting on 25 November 1919 and the establishment was one of the smaller organisations that had come together to form the OA. It accommodated 25 seriously disabled men, whose conditions were so bad that a full-time nursing staff of ten was required. In 1930, the OA was compelled to shut the home when the lease expired. On closure, a trust fund was established which cared for the former residents in alternative facilities for the remainder of their lives.

The OA at Work in the 1930s[18]

The Howitt Agreement: 7.5% of the Poppy Appeal