Shasu

The Shasu (from Egyptian šꜣsw, probably pronounced Shaswe[1]) were Semitic-speaking pastoral nomads in the Southern Levant from the late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age or the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt. They were tent dwellers, organized in clans ruled by a tribal chieftain and were described as brigands active from the Jezreel Valley to Ashkelon and the Sinai.[2] Some of them also worked as mercenaries for Asiatic and Egyptian armies.[3]

Some scholars link the Israelites and YHWH with the Shasu.

Etymology

The name's etymon may be Egyptian šꜣsw, which originally meant "those who move on foot". Levy, Adams, and Muniz report similar possibilities: an Egyptian word that means "to wander", and an alternative Semitic one with the meaning "to plunder".[4]

Land

Though their homeland seems to be in the Transjordan, the Shasu also appear in northern and southern Palestine, Syria and even Egypt.[5]

History

The earliest known reference to the Shasu occurs in a 15th-century BCE list of peoples in the Transjordan region. The name appears in a list of Egypt's enemies inscribed on column bases at the temple of Soleb built by Amenhotep III. Among the details uncovered at the temple was a reference to a place called "Seir, in the land of Shasu" (ta-Shasu se`er, t3-sh3sw s`r), a name thought to be related to or near to Petra, Jordan.[6][7]

In 13th century BCE copies of the column inscriptions ordered by Seti I or by Ramesses II at Amarah-West, six groups of Shasu are mentioned: the Shasu of S'rr, the Shasu of Rbn, the Shasu of Sm't, the Shasu of Wrbr, the Shasu of Yhw, and the Shasu of Pysps.[8][9]

The Shasu continued to dominate the hill country of Cis- and Transjordan between the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron age. The Shasu had become so powerful during this period that they were able to even cut off Egypt's northern routes through Palestine and Transjordan for a while. This in turn prompted vigorous punitive campaigns by Ramesses II and his son Merneptah. After Egyptian abandonment, Canaanite city-states came under the mercy of the Shasu and the Hab/Piru, who were seen as 'mighty enemies'.[3]

The Shasu would eventually be eclipsed by the arrival of the Sea Peoples.[3]

Shasu of Yhw

Two Egyptian texts, one dated to the period of Amenhotep III (14th century BCE), the other to the age of Ramesses II (13th century BCE), refer to tꜣ šꜣśw yhwꜣ, i.e. "The Land of the Shasu yhwꜣ", in which yhwꜣ (also rendered as yhwꜣ or yhw) or Yahu, is a toponym.[10]

| |

| Hieroglyph | Name | Pronunciation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

N16 | tꜣ | |||

|

M8 | šꜣ | |||

|

M23 | sw | |||

|

w | w | |||

|

y | y | |||

|

h | h | |||

|

V4 | wꜣ | |||

|

G1 | ꜣ |

Regarding the name yhwꜣ, Michael Astour observed that the "hieroglyphic rendering corresponds very precisely to the Hebrew tetragrammaton YHWH, or Yahweh, and antedates the hitherto oldest occurrence of that divine name – on the Moabite Stone – by over five hundred years."[11] K. Van Der Toorn concludes: "By the 14th century BC, before the cult of Yahweh had reached Israel, groups of Edomites and Midianites worshipped Yahweh as their god."[12]

Donald B. Redford has argued that the earliest Israelites, semi-nomadic highlanders in central Canaan mentioned on the Merneptah Stele at the end of the 13th century BCE, are to be identified as a Shasu enclave. Since later Biblical tradition portrays Yahweh "coming forth from Seʿir",[13] the Shasu, originally from Moab and northern Edom/Seʿir, went on to form one major element in the amalgam that would constitute the "Israel" which later established the Kingdom of Israel.[14] Per his own analysis of the el-Amarna letters, Anson Rainey concluded that the description of the Shasu best fits that of the early Israelites.[15] If this identification is correct, these Israelites/Shasu would have settled in the uplands in small villages with buildings similar to contemporary Canaanite structures towards the end of the 13th century BCE.[16]

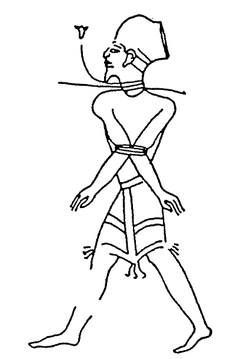

Objections exist to this proposed link between the Israelites and the Shasu, given that the group in the Merneptah reliefs identified with the Israelites are not described or depicted as Shasu (see Merneptah Stele § Karnak reliefs). The Shasu are usually depicted hieroglyphically with a determinative indicating a land, not a people;[17] the most frequent designation for the "foes of Shasu" is the hill-country determinative.[18] Thus they are differentiated from the Canaanites, who are defending the fortified cities of Ashkelon, Gezer, and Yenoam; and from Israel, which is determined as a people, though not necessarily as a socio-ethnic group.[19][a] Scholars point out that Egyptian scribes tended to bundle up "rather disparate groups of people within a single artificially unifying rubric."[21][22]

Frank J. Yurco and Michael G. Hasel would distinguish the Shasu in Merneptah's Karnak reliefs from the people of Israel since they wear different clothing and hairstyles, and are determined differently by Egyptian scribes.[23][24] Lawrence Stager also objected to identifying Merneptah's Shasu with Israelites, since the Shasu are shown dressed differently from the Israelites, who are dressed and hairstyled like the Canaanites.[19][25]

The usefulness of the determinatives has been called into question, though, as in Egyptian writings, including the Merneptah Stele, determinatives are used arbitrarily.[26] Gösta Werner Ahlström countered Stager's objection by arguing that the contrasting depictions are because the Shasu were the nomads, while the Israelites were sedentary, and added: "The Shasu that later settled in the hills became known as Israelites because they settled in the territory of Israel".[25]

Moreover, the hill-country determinative is not always used for Shasu, with the Egyptologist Thomas Schneider connecting references to "Yah", believed to be an abbreviated form of the Tetragrammaton, with the writings in the Shasu-sequence at Soleb and Amarah-West.[27] In an Egyptian Book of the Dead papyrus from the late 18th or 19th dynasty, Schneider identifies a Northwest Semitic theophoric name ‘adōnī-rō‘ē-yāh, meaning "My lord is the shepherd of Yah", which would be the first documented occurrence of the god Yahweh in his function as a shepherd of Yah.[28]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ If the Egyptian scribe was not clear on the nature of the entity he called "Israel," knowing only that it was "different" from the surrounding modalities, then we can imagine something other than a sociocultural Israel. It is possible that Israel represented a confederation of united, but sociologically distinct, modalities that were joined either culturally or politically via treaties and the like. This interpretation of the evidence would allow for the unity implied by the endonymic evidence and also give our scribe some latitude in his use of the determinative.[20]

Citations

- ^ Redford 1992, p. 271.

- ^ Miller 2005, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Younker 1999, p. 203.

- ^ Levy, Adams & Muniz 2004, p. 66.

- ^ Younker 1999, p. 198.

- ^ Grosby 2007, p. 109.

- ^ Gibson, Daniel; Harremoës, Peter. "Names for the city of Petra" (PDF).

- ^ Sivertsen 2009, p. 118.

- ^ Hasel 1998, p. 219.

- ^ Hen 2022.

- ^ Astour 1979, p. 18.

- ^ Van der Toorn 1996, p. 282–283.

- ^ Book of Judges, 5:4 and Deuteronomy, 33:2

- ^ Redford 1992, p. 272–3,275.

- ^ Rainey 2008.

- ^ Shaw & Jameson 2008, p. 313.

- ^ Nestor 2010, p. 185.

- ^ Hasel 2003, p. 32–33.

- ^ a b Stager 2001, p. 92.

- ^ Sparks 1998, p. 108.

- ^ Nestor 2010, p. 186.

- ^ Sparks 1998, p. 105–106.

- ^ Yurco 1986, p. 195, 207.

- ^ Hasel 2003, p. 27–36.

- ^ a b Ahlström 1993, p. 277–278.

- ^ Miller 2005, p. 94.

- ^ Adrom & Müller 2017.

- ^ Schneider 2007.

Sources

- Ahlström, Gösta Werner (1993). The History of Ancient Palestine. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-2770-6.

- Astour, Michael C. (1979). "Yahweh in Egyptian Topographic Lists". In Gorg, M.; Pusch, E. (eds.). Festschrift Elmar Edel. Bamberg. OCLC 464504316.

- William G., Dever (1997). Bartlett, John R. (ed.). "Archaeology and the Emergence of Early Israel". Archaeology and Biblical Interpretation. Routledge: 20–50. doi:10.4324/9780203135877-7. ISBN 9780203135877.

- Hasel, Michael G. (1994). "Israel in the Merneptah Stela". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 296 (296): 45–61. doi:10.2307/1357179. JSTOR 1357179. S2CID 164052192.

- Hasel, Michael G. (1998). "Domination and Resistance: Egyptian Military Activity in the Southern Levant, 1300–1185 BC". Probleme der Ägyptologie. 11. Brill: 217–239. ISBN 9004109846.

- Hasel, Michael G. (2003). Nakhai, Beth Alpert (ed.). "Merenptah's Inscription and Reliefs and the Origin of Israel (The Near East in the Southwest: Essays in Honor of William G. Dever)". Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 58. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research: 19–44. ISBN 0897570650. JSTOR 3768554.

- Hen, Racheli S. (2022). "Signs of YHWH, God of the Hebrews, in New Kingdom Egypt?". Entangled Religions. 12 (2). doi:10.46586/er.12.2021.9463. ISSN 2363-6696. S2CID 246697144.

- Hoffmeier, James K. (2005). "Ancient Israel in Sinai". Buried History, 41, 2005, 69-70. Oxford University Press: 240–45.

- Levy, Thomas E.; Adams, Russell B.; Muniz, Adolfo (January 2004). "Archaeology and the Shasu Nomads". In Richard Elliott Friedman; William Henry Propp (eds.). Le-David Maskil: A Birthday Tribute for David Noel Freedman. Eisenbrauns. pp. 66–. ISBN 978-1-57506-084-2.

- Grosby, Steven (2007). Leoussi, Athena (ed.). Nationalism and Ethnosymbolism: History, Culture and Ethnicity in the Formation of Nations. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748629350.

- MacDonald, Burton (1994). "Early Edom: The Relation between the Literary and Archaeological Evidence". In Coogan, Michael D.; Cheryl, J.; Stager, Lawrence (eds.). Scripture and Other Artifacts: Essays on the Bible and Archaeology in Honor of Philip J. King. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 230–246. ISBN 0664223648.

- Miller, Robert D. (2005). "Chieftains of the Highland Clans: A History of Israel in the 12th and 11th Centuries B.C." Near Eastern Archaeology. 69 (2). Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing: 99. doi:10.1086/NEA25067653.

- Nestor, Dermot Anthony (2010). "Cognitive Perspectives on Israelite Identity". Reviews in Religion & Theology. 19 (1). Continuum International Publishing Group: 141–143. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9418.2011.00993.x.

- Rainey, Anson (2008). "Shasu or Habiru. Who Were the Early Israelites?". Biblical Archaeology Review. 34 (6). S2CID 163463129.

- Redford, Donald B. (1992). Egypt, Canaan and Israel In Ancient Times. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00086-7.

- Schneider, Thomas (2007). "The First Documented Occurence [sic] of the God Yahweh? (Book of the Dead Princeton "Roll 5")". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. 7 (2): 113–120. doi:10.1163/156921207783876422.

- Shaw, Ian; Jameson, Robert, eds. (2008). "Shasu". Dictionary of Archaeology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470751961.

- Sivertsen, Barbara J. (2009). The Parting of the Sea: How Volcanoes, Earthquakes, and Plagues Shaped the Story of Exodus. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691137704.

- Sparks, Kenton L. (1998). Ethnicity and Identity in Ancient Israel: Prolegomena to the Study of Ethnic Sentiments and Their Expression in the Hebrew Bible. Eisenbrauns. doi:10.5325/j.ctv1w36q0h. ISBN 9781575065168. JSTOR 10.5325/j.ctv1w36q0h.

- Stager, Lawrence E. (2001). "Forging an Identity: The Emergence of Ancient Israel". In Coogan, Michael (ed.). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. pp. 90–129. ISBN 0195087070.

- Van der Toorn, K. (1996). Family Religion in Babylonia, Ugarit and Israel: Continuity and Changes in the Forms of Religious Life. Brill. ISBN 9004104100.

- Adrom, Faried; Müller, Matthias (2017). "The Tetragrammaton in Egyptian Sources – Facts and Fiction". In Van Oorschot, Jürgen; Witte, Markus (eds.). The Origins of Yahwism. De Gruyter. pp. 93–. doi:10.1515/9783110448221. ISBN 9783110448221.

- Younker, Randall W. (1999). "The Emergence of the Ammonites". In MacDonald, Burton; Younker, Randall W. (eds.). Ancient Ammon. BRILL. p. 203. ISBN 978-90-04-10762-5.

- Yurco, Frank J. (1986). "Merenptah's Canaanite Campaign". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 23: 189–215. doi:10.2307/40001099. JSTOR 40001099.