Grand Western Canal

Grand Western Canal Plan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Grand Western Canal ran between Taunton in Somerset and Tiverton in Devon in the United Kingdom. The canal had its origins in various plans, going back to 1796, to link the Bristol Channel and the English Channel by a canal, bypassing Lands End. An additional purpose of the canal was the supply of limestone and coal to lime kilns along with the removal of the resulting quicklime, which was used as a fertiliser and for building houses. This intended canal-link was never completed as planned, as the coming of the railways removed the need for its existence.[1]

Construction was in two phases. A level section, from Tiverton to Lowdwells on the Devon/Somerset border, opened in 1814, and was capable of carrying broad-beam barges, carrying up to 40 tons. The Somerset section, suitable for tub boats (which were about 20 feet (6 m) long and capable of carrying eight tons) opened in 1839. It included an inclined plane and seven boat lifts, the earliest lifts to see commercial service in the UK. The lifts predated the Anderton Boat Lift by nearly 40 years.

The 11 miles of Devon section remains open, despite various threats to its future, and is now a designated country park and local nature reserve, and allows navigation. The Somerset section was closed in 1867, and is gradually disappearing from the landscape, although sections are now used as a footpath. It maintains a historical interest and has been subject to some archaeological excavations.

History

The Grand Western Canal was conceived as one of several competing schemes to alleviate the hazards and delays of coastal sailing ships making a passage around Land's End to get between the Bristol Channel and the English Channel.[2] A canal from the mouth of the River Exe to Exeter had been opened in 1566; and eight miles of the River Tone had been made navigable in 1638. Navigation of the River Tone had been extended to Taunton in 1717, by the construction of locks on the upper section.[3]

Against this background, in 1768 a committee commissioned James Brindley to survey a route, in the form of a canal, between Taunton and Exeter; and the survey was duly carried out by Robert Whitworth in 1769. This was to have been called the Exeter to Uphill Canal, as it involved a route from Topsham or Exeter to Taunton, then the use of the River Tone and a second canal from Burrow Bridge, via Bridgwater, Glastonbury, Wells and Axbridge, to Uphill, near Weston-super-Mare.[2] Nothing further came of the plan until the 1790s, when various canal engineers were consulted, and in 1794 John Rennie was asked by a different committee, the Grand Western Canal Committee, to make another survey, which was adopted, and formed the basis for a planned Act of Parliament. Opposition from the City of Exeter, who feared it would compete with the Exeter Canal for transportation of coal, was eventually softened; and the Act was passed on 24 March 1796.[4][5]

The Act authorised a canal from Taunton to Topsham with branches to Tiverton and Cullompton. Water supply would be derived from proposed reservoirs, one on the River Tone and two on the River Culm, and from any other available sources within 2,000 yards (1.8 km) of the line of the canal.[6] The canal company was also authorised to improve the River Tone near Taunton, and to raise £220,000, plus an additional £110,000 if required. Navigation onwards from Taunton was via the River Tone and the River Parrett.[7] Construction did not start immediately.[8]

Construction

Grand Western Canal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Finally in 1810, work started under the direction of John Thomas. Surprisingly, the decision was taken to start in the middle, with a 2+1⁄2-mile (4 km) section of the main line and the 9-mile (14 km) branch to Tiverton. The logic for this was that there was a large potential trade in limestone between quarries at Canonsleigh and Tiverton, and this would generate income.[9] The summit level was cut 16 feet (5 m) lower than the original plans, so that no locks would be required, but this greatly increased the amount of earthworks required.[10] A further Act was obtained in 1811 to sanction this, and to re-route the canal near Halberton,[11] where Rock Bridge was constructed to carry the road over the canal.[12] The same engineers that built the canal also built a substantial country house,[13] turnpike house[14] and cottages[15] at the site. Several other bridges, including Batten's Bridge,[16] Crownhills Bridge,[17] Greenway Bridge[18] and Sellick Bridge[19] were also constructed at Halberton to carry minor roads over the canal.

With costs much higher than anticipated, work ceased in June 1811. After much deliberation, it was decided to continue construction, and to obtain a third Act of Parliament to authorise increased charges for carriage of goods. By 1812, progress was being made, but was hampered by the need for rock cuttings at Holcombe Rogus. Leakage also meant that some sections needed to be lined with puddle clay. Lime kilns were constructed to provide the materials. These kilns can still be seen beside the canal,[20] close to the Waytown Tunnel.[21] Fenacre Bridge[22] and Fossend Bridge[23] were constructed at Burlescombe, where culverts were also needed to manage the streams.[24] At a total cost of £244,505, the canal was opened on 25 August 1814, when the first boat travelled from Lowdwells to Tiverton, laden with coal.[25]

At Sampford Peverell two rectories were built in 1836, at the expense of the Grand Western Canal Company, in compensation for cutting through the grounds and demolishing the south wing of the Old Rectory.[26][27] Two road bridges were also needed in the village.[28][29]

Second phase

Traffic on the opened section was much lower than anticipated, and the prospects of building the rest of the canal dwindled, as profits were minimal.[30] However, in 1829 James Green turned his attention to the link to Taunton. He had been the architect of the Bude Canal, which was built for tub-boats and used inclined planes to change levels, and proposed a similar solution here.[31] The Bridgwater and Taunton Canal had opened in 1827, making navigation from Taunton to Bridgwater easier than on the River Tone.[32] In a report of 1830, Green proposed using vertical lifts instead of inclined planes, and estimated the cost of the canal at £65,000.[33]

Work started in 1831, and progressed quickly, including the construction of a bridge at Bradford on Tone[34] and Harpford Bridge at Langford Budville,[35] where a new warehouse was also built.[36] In addition to the boat lift in Nynehead[37][38] two aqueducts were required within the village.[39][40]

The original Act of 1796 had envisaged the canal joining the River Tone at Taunton, and made provision for the improvement of some 500 yards (460 m) of the river, which would then be granted to the canal company and effectively become part of the canal. They could build warehouses and wharves on this section.[41] By late 1830, there was considerable hostility between the Conservators of the River Tone and the new Bridgwater and Taunton Canal company, who had constructed a connection into the river at Firepool, so that barges could reach Taunton Bridge. The Conservators had retaliated by reducing the water supply to the canal. Litigation followed, and the Grand Western Canal company, having decided that a direct connection to the Bridgwater and Taunton Canal was a better option, had succeeded in purchasing the land required by agreement with landowners.[42]

Meanwhile, as a result of the litigation, an Act of Parliament was obtained in 1832 which required the Bridgwater and Taunton Canal to build a link between the Tone and the Grand Western Canal. This was built in 1834, leaving the Tone below French Weir, and heading north-west to Frieze Hill, where there was a right-angled connection to the line of the canal. Although there is little evidence that it was ever used, it appeared on the 1840 tithe map, on John Wood's town plan of the same year,[43] and on the 1890 Ordnance Survey map.[44] Plans for the main line of the canal included seven lifts and one inclined plane, and it was these features that caused the subsequent delay in the completion of the canal. Teething problems with the design of the lifts gradually came to light, and although the cost of rectifying these was borne by Green, the canal could not be opened. There were also problems with the inclined plane. The canal was partially opened to Wellington, in 1835, but in January 1836, Green was dismissed.[45]

Completion

The engineer W A Provis was asked to survey the works, and to report on the lifts and the causes of the failure of the plane. His clear report is an important source of information on the canal at the time of its construction.[46] Some remedial work was instigated, following the report, including the provision of a steam engine to power the Wellisford incline. The 14-mile (23 km) extension was fully opened on 28 June 1838, at a cost of about £80,000.[47]

Boat lifts

Green's use of boat lifts was innovative. The idea was not new, as he acknowledged in an article describing the lifts which he published in Transactions[48] in 1838, having been suggested in principle by James Anderson of Edinburgh in 1796. Robert Weldon had tried to build one at Combe Hay on the Somersetshire Coal Canal in 1798, which was replaced by a lock flight after persistent failures. One was built at Ruabon on the Ellesmere Canal in 1796, but was replaced as it was not robust enough for regular use. James Fussell built one on the abortive Dorset and Somerset Canal, but the works were abandoned before it was ever used regularly. The lift at Tardebigge on the Worcester and Birmingham Canal was replaced by locks in 1815 as it was "too complex and delicate", according to Rennie. Finally, another lift at Camden Town on the Regent's Canal was replaced by locks in 1815 because it could not be made to work.[49]

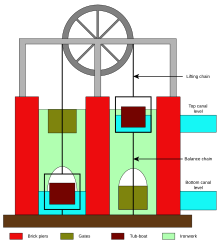

Principles

With no working prototypes, Green set about building seven lifts. The principle was simple. Two caissons were suspended from three carrying wheels of 16 feet (5 m) diameter, by wrought iron chains. The caisson at the bottom was jacked against the front wall of the lift to seal it, and a door or gate was opened to allow the boat to float in. The caisson at the top was jacked against the back wall in a similar manner. When both boats were in, the doors on the caissons and lift were closed, and the jacks released. Because a boat displaces its own weight in water, the system should be balanced, and a small amount of energy is required to start the boats moving. When the top caisson reaches the bottom, the jacks are applied, the doors are opened, and the boats can continue.[50]

In order to maintain the balance, a second chain was fixed to the bottom of the caisson, so that the total length of chain on each side of the lift remained the same. As a caisson descended, the chain coiled up at the bottom of the lift. The small amount of energy was created by ensuring that the ascending caisson was a little too low by the time the descending one reached the bottom. Thus it would hold a greater depth of water by the time it was ready to descend again. In practice, about 2 inches (5 cm) of water, weighing about a ton, was found to be sufficient.[51]

Problems

The difficulty was that Anderson had suggested that the water in the caisson chambers should be at a lower level than that in the canal. This had not been implemented, and so the lower caisson would not sink deep enough for either boat to be floated out. Attempts to fit gates and to let the water in the chamber drain to waste had proved ineffective. Ultimately, lock chambers were built at the foot of each lift. These were filled with water from the upper level, so that the boat could float out, and it then descended the final 3 feet (0.9 m) as it would in a conventional lock. Only the lift at Greenham used Anderson's principle, and included a proper drain to lower the level in the chambers.[52]

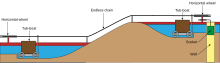

With the inclined plane, the problems stemmed from a miscalculation. Power was provided by a large tank, filled with water, which descended in a shaft, raising one boat on a trolley and allowing another to descend as it did so. When the tank reached the bottom of the shaft, the water discharged, and the second tank was used to reverse the process. Green had been the engineer on the Bude Canal, where this design had been used successfully, but the size of the tanks at Wellisford were much too small. On the Bude Canal, a tank holding 15 tons of water was required to raise a boat weighing six tons. The Grand Western Canal used boats holding eight tons, but the tanks only held ten tons of water, whereas tests indicated that about 25 tons was needed.[53] It was for this reason that the steam engine was obtained to supply the power.[54]

Operation

The Somerset section of the canal was suitable for tub-boats, which were about 20 feet (6.1 m) long and capable of carrying eight tons. The Devon section was suitable for larger broad-beam barges, carrying up to 40 tons.[55] Income from tolls increased steadily from £971 in 1835, rising to £2,754 in 1838 and £4,926 in 1844.[56] At this point, competition from the railways started. The Bristol and Exeter Railway reached Taunton in 1842 and Exeter in 1844. A branch to Tiverton was opened in 1848, and although the canal company received £1,200 for loss of trade while an aqueduct was constructed over the line of the railway, deficits started to mount up almost immediately.[57]

In 1853, with income no longer meeting operational costs, the canal was leased to the Bristol and Exeter Railway.[58] From 1854, the company started to pay a dividend to its shareholders of 0.2%.[59] Just ten years later, an Act of Parliament was obtained to sell the canal to the railway company and to abandon the Somerset section of the canal. The transfer took place on 13 April 1865,[60] and the tub-boat canal was closed in 1867. The lifts were dismantled, and most of the route sold back to the original landowners.[61]

Decline

Limestone traffic continued on the Tiverton section.[61] Only two boats were working the canal by 1904, and the last commercial traffic was roadstone from Whipcott quarry to Tiverton, where there were lime kilns and a crushing plant. Around 7,000 tons per year were transported up to 1925.[62] After this the only income was from the washing of sheep, for which a charge was made for every 20 sheep, and the sale of water lilies which grew in the canal.[63] In the 1930s, dams were built at both ends of a section near Halberton, where persistent leakage could not be cured.[64]

Having passed into the ownership of the Great Western Railway in 1888, the canal became the responsibility of the British Transport Commission when the railways were nationalised in 1948, and was formally closed in 1962. The responsibility for it passed to the British Waterways Board in 1964.[65]

Restoration

With various plans for using the route of the canal for landfill and for a bypass, some local interest was aroused regarding its future. The Tiverton Canal Preservation Committee was formed in 1962. This committee was stirred to action by plans in 1966 to infill parts of the canal so that housing could be built over it. Tiverton Borough Council gave the committee the power to negotiate with the British Waterways Board in March 1967, but the Board were unwilling to offer financial assistance.[66]

Changes in legislation aided the cause. From 1968, county councils could set up country parks, under the Countryside Act 1968, and the Transport Act 1968 enabled the British Waterways Board to allow local authorities to maintain or purchase inland waterways. By 1969, BWB had stated that they were prepared to hand over the canal to Devon County Council, together with some money for maintenance.[67] With some representatives within the council wavering, the preservation committee organised a walk along the entire canal on 18 October 1969. Around 400 walkers set off, with the local member of Parliament firing a starting gun, and by the time Tiverton was reached, the party totalled about 1200 people.[68]

Handover

By April 1970, the British Waterways Board had agreed to give the canal to Devon County Council, with £30,000 for maintenance.[69] The actual contract was signed on 5 May 1971 at Tiverton Town Hall, when General Sir Hugh Stockwell of the BWB also handed over a cheque for £38,750 to Colonel Eric Palmer, chairman of Devon County Council. The transfer of the canal was effective from 24 June 1971.[70]

The new owners set to work immediately. The dry section was excavated and lined with a butyl liner to prevent leakage. The canal was reopened in 1971.[71] Navigation was restricted to unpowered boats, with the exception of a maintenance boat that was used for cutting weed, while the final section from Fossend to Lowdwells, which would have been part of the original main line to Exeter, is designated as a nature reserve, and so all navigation and angling is discouraged.[72] The canal is now a designated country park, and a horse-drawn tourist narrowboat runs from Tiverton. Since 2003 powered boats have been allowed on the Canal, subject to Licence from Devon County Council. The Canal is also a very popular Coarse Fishing spot and angling rights on the Canal are leased to the Tiverton and District Angling Club. In addition to holding a valid Environment Agency Rod Licence, a permit must be purchased in advance.

The Somerset section is largely dry and is gradually disappearing into the landscape, as a result of roads improvements and ploughing, but a footpath has been established along much of its route, and archaeological excavations of the lift at Nynehead, the only one where there are still substantial remains,[37][38] were carried out between 1998 and 2003 by the Somerset Industrial Archaeological Society.[73]

Extension

In Summer 2017, the Friends of the Grand Western Canal announced a scheme to rebuild around 2 miles (3 km) of canal on the western approaches of Taunton. This would see a replica of one of Green's boat lifts constructed near the Silk Mills park and ride car park, and a new canal built across empty public land to join the Tone below French Weir, roughly following the link constructed by the Bridgwater and Taunton Canal in 1834. Above the working lift, 1⁄2 mile (0.80 km) of the canal would be restored to provide moorings for boats using the lift. The scheme is supported by local MPs and by Taunton Council. The Friends are hoping to carry out a feasibility study in 2018, at a cost of £35,000.[74] A competition to design the boat lift using modern materials and energy efficient mechanisms, but remaining faithful to Green's basic design, has been launched, and is supported by the engineers Clarke Bond, the Institution of Civil Engineers and the University of Exeter.[75]

2012 breach and repair

Exceptionally heavy rainfall in November 2012 caused a major break in the Grand Western Canal's banks, near Halberton, necessitating nearby homes to be evacuated.[76] Two temporary dams were installed which allowed the rest of the canal to remain open[77] and meant the horse drawn barge at Tiverton was able to run throughout the summer of 2013.[78] Around 400 fish were returned to the canal from a flooded field but many fish including pike, eels, perch, bream, tench and roach were lost. About 25 people from the Environment Agency and Tiverton Angling Club assisted with saving the fish.[79] The Environment Agency restocked the canal with 3,000 fish in January 2013 and by May the Environment Agency said they were flourishing.[80]

Devon County Council agreed to pay for repairs to the canal, in time for its 200th anniversary and on 7 July 2013, a £3 million project to repair the breach, began with an official turf cutting. The repairs included rebuilding the failed embankment and raising the level to reduce the risk of overtopping in the future, and further improvements to water management. The canal was lined with an impermeable material along the length of the embankment.[81] In addition a water level monitoring and alarm system has been installed. This system has sensors in Tiverton and Burlescombe and alerts the canal rangers and Devon County Council if the levels become exceptionally high.[82] Refilling of the breached section began on 4 March 2014 using a sluice gate at Rock Bridge which gradually filled the empty section[83] and the canal was officially re-opened on 19 March 2014 by chairman of Devon County Council Councillor Bernard Hughes. Six narrow boats, led by Chairman of Halberton Parish Council, Councillor Ken Browse, were the first to travel on the new section.[84]

See also

References

- ^ Hadfield 1967, p. 37.

- ^ a b Hadfield 1967, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 11.

- ^ Hadfield 1967, pp. 95–97.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 20–25.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 26.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 30.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 34.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 37.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Historic England. "Rock Bridge at Halberton (1106646)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Rock House and adjacent range of outbuildings (1306712)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Turnpike Cottage (1106648)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Cottage 100 metres east of Rock - House (1106647)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Batten's Bridge (1105877)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Crownhills Bridge (1105883)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Greenway Bridge (1106641)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Sellick Bridge (1105890)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Waytown Limekilns (1140142)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Waytown Tunnel (1325913)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Fenacre Bridge at Burlescombe (1236822)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Fossend Canal Bridge at Burlescombe (1325865)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Twin Culverts at Burlescombe (1140104)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Harris (1996), p. 55.

- ^ Historic England. "Sampford Peverell The Old Rectory (1106393)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Sampford Peverell The Rectory (1106393)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Sampford Peverell Bridge (1106398)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Buckland Bridge (1307072)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 56.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 65–67.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 62.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 70, 74.

- ^ Historic England. "Bridge over Grand Western Canal at Trefusis Farm, Bradford on Tone (1344546)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Harpford Bridge over remains of Grand Western Canal, Langford Budville (1060349)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Warehouse about 25 m west of Harpford Bridge, Langford Budville (1176927)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Remains of vertical lift on former Grand Western Canal. (1177043)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ a b "The Boat Lift on The Grand Western at Nynehead". Nynehead Village Web Site. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

- ^ Historic England. "Aqueduct, formerly carrying Grand Western Canal over driveway to Nynehead Court (1307612)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Aqueduct formerly carrying the Grand Western Canal over the River Tone, now disused (1060354)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 25, 27.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 77.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Ordnance Survey, 1:2500 map, Taunton

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 99.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 100.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Transactions of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Volume 2, 1838

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 84–87.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 87–91.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 92.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 111.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 112.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 112, 114.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 120.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 122.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b Harris 1996, p. 132.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 134.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 139.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 140-141.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 142–146.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 158.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 161.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 163.

- ^ Harris 1996, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Harris 1996, p. 164.

- ^ "The Boat Lifts of the Grand Western Canal, Denis Dodd, Railway and Canal Historical Society" (PDF). pp. 291–292. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- ^ Denny 2017, p. 74.

- ^ "Grand Western Canal Boat Lift Competition". Clarke Bond. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ "Grand Western Canal breach captured at Halberton, Devon". BBC News. 22 November 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ "Grand Western Canal repairs costing £3m begin". BBC News. 8 July 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ "Impact of flooding on key business sectors in Devon and Somerset 2012-13" (PDF). SQW. 16 July 2013. p. 35. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^ "Breached Grand Western Canal to be restocked with fish". BBC News. 16 December 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ "Fish stock in breached Grand Western Canal now 'flourishing'". BBC News. 11 May 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ "Turf cutting marks start of Grand Western Canal repairs". Tivertonian. 9 July 2013. Archived from the original on 15 July 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ Wevill; Richard (7 January 2014). "Water levels managed 'better than ever before'". Culm Valley Gazette. p. 14.

- ^ "Water pours back into repaired section of Tiverton canal". Mid Devon Gazette. 4 March 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ "Narrow boats return for first journey on fixed canal". Mid Devon Gazette. 19 March 2014. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

Bibliography

- Denny, Andrew (November 2017). Grand Western Canal. Waterways World. ISSN 0309-1422.

- Hadfield, Charles (1967). The Canals of South West England. David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-4176-6.

- Harris, Helen (1996). The Grand Western Canal. Devon Books. ISBN 978-0-86114-901-8.

External links

- Grand Western Canal home page (on Devon County Council website)

- GWC Information

- images & map of mile markers seen along the Grand Western canal