W. S. Gilbert

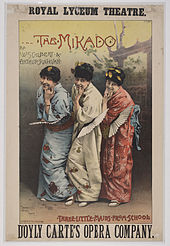

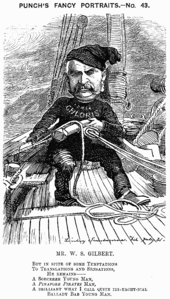

Sir William Schwenck Gilbert (18 November 1836 – 29 May 1911) was an English dramatist, librettist, poet and illustrator best known for his collaboration with composer Arthur Sullivan, which produced fourteen comic operas. The most famous of these include H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance and one of the most frequently performed works in the history of musical theatre, The Mikado.[1] The popularity of these works was supported for over a century by year-round performances of them, in Britain and abroad, by the repertory company that Gilbert, Sullivan and their producer Richard D'Oyly Carte founded, the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company. These Savoy operas are still frequently performed in the English-speaking world and beyond.[2]

Gilbert's creative output included over 75 plays and libretti, and numerous short stories, poems and lyrics, both comic and serious. After brief careers as a government clerk and a lawyer, Gilbert began to focus, in the 1860s, on writing light verse, including his Bab Ballads, short stories, theatre reviews and illustrations, often for Fun magazine. He also began to write burlesques and his first comic plays, developing a unique absurdist, inverted style that would later be known as his "topsy-turvy" style. He also developed a realistic method of stage direction and a reputation as a strict theatre director. In the 1870s, Gilbert wrote 40 plays and libretti, including his German Reed Entertainments, several blank-verse "fairy comedies", some serious plays, and his first five collaborations with Sullivan: Thespis, Trial by Jury, The Sorcerer, H.M.S. Pinafore and The Pirates of Penzance. In the 1880s, Gilbert focused on the Savoy operas, including Patience, Iolanthe, The Mikado, The Yeomen of the Guard and The Gondoliers.

In 1890, after this long and profitable creative partnership, Gilbert quarrelled with Sullivan and Carte concerning expenses at the Savoy Theatre; the dispute is referred to as the "carpet quarrel". Gilbert won the ensuing lawsuit, but the argument caused hurt feelings among the partnership. Although Gilbert and Sullivan were persuaded to collaborate on two last operas, they were not as successful as the previous ones. In later years, Gilbert wrote several plays, and a few operas with other collaborators. He retired, with his wife Lucy, and their ward, Nancy McIntosh, to a country estate, Grim's Dyke. He was knighted in 1907. Gilbert died of a heart attack while attempting to rescue a young woman to whom he was giving a swimming lesson in the lake at his home.

Gilbert's plays inspired other dramatists, including Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw,[3] and his comic operas with Sullivan inspired the later development of American musical theatre, especially influencing Broadway librettists and lyricists. According to The Cambridge History of English and American Literature, Gilbert's "lyrical facility and his mastery of metre raised the poetical quality of comic opera to a position that it had never reached before and has not reached since".[4]

Early life and career

Beginnings

| "No sooner had the learned judge pronounced this sentence than the poor soul stooped down, and taking off a heavy boot, flung it at my head, as a reward for my eloquence on her behalf; accompanying the assault with a torrent of invective against my abilities as a counsel, and my line of defence." |

| — My Maiden Brief[5]

(Gilbert claimed this incident was autobiographical.)[6] |

Gilbert was born at 17 Southampton Street, Strand, London. His father, also named William, was briefly a naval surgeon, who later became a writer of novels and short stories, some of which his son illustrated. Gilbert's mother was the former Anne Mary Bye Morris (1812–1888), the daughter of Thomas Morris, an apothecary.[7] Gilbert's parents were distant and stern, and he did not have a particularly close relationship with either of them. They quarrelled increasingly, and following the break-up of their marriage in 1876, his relationships with them, especially his mother, became even more strained.[8] Gilbert had three younger sisters, two of whom were born outside England because of the family's travels during these years: Jane Morris (b. 1838 in Milan, Italy – 1906), who married Alfred Weigall, a miniatures painter; Mary Florence (b. 1843 in Boulogne, France – 1911); and Anne Maude (1845–1932). The younger two never married.[9][10] Gilbert was nicknamed "Bab" as a baby, and then "Schwenck", after the surname of his great aunt and great uncle, who were also his father's godparents.[7]

As a child, Gilbert travelled to Italy in 1838 and then France for two years with his parents, who finally returned to settle in London in 1847. He was educated at Boulogne, France, from the age of seven (he later kept his diary in French so that the servants could not read it),[11] then at Western Grammar School, Brompton, London, and then at the Great Ealing School, where he became head boy and wrote plays for school performances and painted scenery. He then attended King's College London, graduating in 1856. He intended to take the examinations for a commission in the Royal Artillery, but with the end of the Crimean War, fewer recruits were needed, and the only commission available to Gilbert would have been in a line regiment. Instead he joined the Civil Service: he was an assistant clerk in the Privy Council Office for four years and hated it. In 1859, he joined the Militia, a part-time volunteer force formed for the defence of Britain, which he served in until 1878 (in between writing and other work), reaching the rank of captain.[12][n 1] In 1863, he received a bequest of £300 that he used to leave the civil service and take up a brief career as a barrister (he had already entered the Inner Temple as a student). His legal practice was not successful, averaging just five clients a year.[14]

To supplement his income from 1861 on, Gilbert wrote a variety of stories, comic rants, grotesque illustrations, theatre reviews (many in the form of a parody of the play being reviewed),[15] and, under the pseudonym "Bab" (his childhood nickname), illustrated poems for several comic magazines, primarily Fun, started in 1861 by H. J. Byron. He published stories, articles, and reviews in papers such as The Cornhill Magazine, London Society, Tinsley's Magazine and Temple Bar. In addition, Gilbert was the London correspondent for L'Invalide Russe and a drama critic for the Illustrated London Times. In the 1860s he also contributed to Tom Hood's Christmas annuals, to Saturday Night, the Comic News and the Savage Club Papers. The Observer newspaper in 1870 sent him to France as a war correspondent reporting on the Franco-Prussian War.[7]

The poems, illustrated humorously by Gilbert, proved immensely popular and were reprinted in book form as the Bab Ballads.[16][n 2] He would later return to many of these as source material for his plays and comic operas. Gilbert and his colleagues from Fun, including Tom Robertson, Tom Hood, Clement Scott and F. C. Burnand (who defected to Punch in 1862) frequented the Arundel Club, the Savage Club, and especially Evans's café, where they had a table in competition with the Punch 'Round table'.[17][n 3]

After a relationship in the mid-1860s with the novelist Annie Thomas,[19] Gilbert married Lucy Agnes Turner (1847–1936), whom he called "Kitty", in 1867; she was 11 years his junior. He wrote many affectionate letters to her over the years. Gilbert and Lucy were socially active both in London and later at Grim's Dyke, often holding dinner parties and being invited to others' homes for dinner, in contrast to the picture painted by fictionalisations such as the film Topsy-Turvy. The Gilberts had no children, but they had many pets, including some exotic ones.[20]

First plays

Gilbert wrote and directed several plays at school, but his first professionally produced play was Uncle Baby, which ran for seven weeks in the autumn of 1863.[n 4]

In 1865–66, Gilbert collaborated with Charles Millward on several pantomimes, including one called Hush-a-Bye, Baby, On the Tree Top, or, Harlequin Fortunia, King Frog of Frog Island, and the Magic Toys of Lowther Arcade (1866).[22] Gilbert's first solo success came a few days after Hush-a-Bye Baby premiered. His friend and mentor, Tom Robertson, was asked to write a pantomime but did not think he could do it in the two weeks available, and so he recommended Gilbert instead. Written and rushed to the stage in 10 days, Dulcamara, or the Little Duck and the Great Quack, a burlesque of Gaetano Donizetti's L'elisir d'amore, proved extremely popular. This led to a long series of further Gilbert opera burlesques, pantomimes and farces, full of awful puns (traditional in burlesques of the period),[23] though showing, at times, signs of the satire that would later be a defining part of Gilbert's work.[4][n 5] For instance:

That men were monkeys once – to that I bow;

(looking at Lord Margate) I know one who's less man than monkey, now;

That monkeys once were men, peers, statesmen, flunkies –

That's rather hard on unoffending monkeys![23]

This was followed by Gilbert's penultimate operatic parody, Robert the Devil, a burlesque of Giacomo Meyerbeer's opera, Robert le diable, which was part of a triple bill that opened the Gaiety Theatre, London, in 1868. The piece was Gilbert's biggest success to date, running for over 100 nights and being frequently revived and played continuously in the provinces for three years thereafter.[24]

In Victorian theatre, "[to degrade] high and beautiful themes ... had been the regular proceeding in burlesque, and the age almost expected it"[4] However, Gilbert's burlesques were considered unusually tasteful compared to the others on the London stage. Isaac Goldberg wrote that these pieces "reveal how a playwright may begin by making burlesque of opera and end by making opera of burlesque."[25] Gilbert would depart even further from the burlesque style from about 1869 with plays containing original plots and fewer puns. His first full-length prose comedy was An Old Score (1869).[26]

German Reed entertainments and other plays of the early 1870s

Theatre, at the time Gilbert began writing, had fallen into disrepute. Badly translated and adapted French operettas and poorly written, prurient Victorian burlesques dominated the London stage. As Jessie Bond vividly described it, "stilted tragedy and vulgar farce were all the would-be playgoer had to choose from, and the theatre had become a place of evil repute to the righteous British householder."[27] Bond created the mezzo-soprano roles in most of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas, and is here leading into a description of Gilbert's role reforming the Victorian theatre.[27]

From 1869 to 1875, Gilbert joined with one of the leading figures in theatrical reform, Thomas German Reed (and his wife Priscilla), whose Gallery of Illustration sought to regain some of theatre's lost respectability by offering family entertainments in London.[27] So successful were they that by 1885 Gilbert stated that original British plays were appropriate for an innocent 15-year-old girl in the audience.[n 6] Three months before the opening of Gilbert's last burlesque (The Pretty Druidess), the first of his pieces for the Gallery of Illustration, No Cards, was produced. Gilbert created six musical entertainments for the German Reeds, some with music composed by Thomas German Reed.[28]

The environment of the German Reeds' intimate theatre allowed Gilbert quickly to develop a personal style and freedom to control all aspects of production, including set, costumes, direction and stage management.[29] These works were a success,[30] with Gilbert's first big hit at the Gallery of Illustration, Ages Ago, opening in 1869. Ages Ago was also the beginning of a collaboration with the composer Frederic Clay that would last seven years and produce four works.[31] It was at a rehearsal for Ages Ago that Clay formally introduced Gilbert to his friend, Arthur Sullivan.[31][n 7][32] The Bab Ballads and Gilbert's many early musical works gave him much practice as a lyricist even before his collaboration with Sullivan.

Many of the plot elements of the German Reed Entertainments (as well as some from his earlier plays and Bab Ballads) would be reused by Gilbert later in the Gilbert and Sullivan operas. These elements include paintings coming to life (Ages Ago, used again in Ruddigore), a deaf nursemaid binding a respectable man's son to a "pirate" instead of to a "pilot" by mistake (Our Island Home, 1870, reused in The Pirates of Penzance), and the forceful mature lady who is "an acquired taste" (Eyes and No Eyes, 1875, reused in The Mikado).[33] During this time, Gilbert perfected the 'topsy-turvy' style that he had been developing in his Bab Ballads, where the humour was derived by setting up a ridiculous premise and working out its logical consequences, however absurd.[34] Mike Leigh describes the "Gilbertian" style as follows: "With great fluidity and freedom, [Gilbert] continually challenges our natural expectations. First, within the framework of the story, he makes bizarre things happen, and turns the world on its head. Thus the Learned Judge marries the Plaintiff, the soldiers metamorphose into aesthetes, and so on, and nearly every opera is resolved by a deft moving of the goalposts ... His genius is to fuse opposites with an imperceptible sleight of hand, to blend the surreal with the real, and the caricature with the natural. In other words, to tell a perfectly outrageous story in a completely deadpan way."[35]

At the same time, Gilbert created several "fairy comedies" at the Haymarket Theatre. This series of plays was founded upon the idea of self-revelation by characters under the influence of some magic or some supernatural interference.[36] The first was The Palace of Truth (1870), based partly on a story by Madame de Genlis. In 1871, with Pygmalion and Galatea, one of seven plays that he produced that year, Gilbert scored his greatest hit to date. Together, these plays and their successors such as The Wicked World (1873), Sweethearts (1874), and Broken Hearts (1875), did for Gilbert on the dramatic stage what the German Reed entertainments had done for him on the musical stage: they established that his capabilities extended far beyond burlesque, won him artistic credentials, and demonstrated that he was a writer of wide range, as comfortable with human drama as with farcical humour. The success of these plays, especially Pygmalion and Galatea, gave Gilbert a prestige that would be crucial to his later collaboration with as respected a musician as Sullivan.[37]

| "It is absolutely essential to the success of this piece that it should be played with the most perfect earnestness and gravity throughout. There should be no exaggeration in costume, makeup or demeanour; and the characters, one and all, should appear to believe, throughout, in the perfect sincerity of their words and actions. Directly the actors show that they are conscious of the absurdity of their utterances the piece begins to drag." |

| — Preface to Engaged |

During this period, Gilbert also pushed the boundaries of how far satire could go in the theatre. He collaborated with Gilbert Arthur à Beckett on The Happy Land (1873), a political satire (in part, a parody of his own The Wicked World), which was briefly banned because of its unflattering caricatures of Gladstone and his ministers.[38] Similarly, The Realm of Joy (1873) was set in the lobby of a theatre performing a scandalous play (implied to be the Happy Land), with many jokes at the expense of the Lord Chamberlain (the "Lord High Disinfectant", as he is referred to in the play).[39] In Charity (1874), however, Gilbert uses the freedom of the stage in a different way: to provide a tightly written critique of the contrasting ways that Victorian society treated men and women who had sex outside of marriage. These works anticipated the 'problem plays' of Shaw and Ibsen.[40]

As director

Once he became established, Gilbert was the stage director for his plays and operas and had strong opinions on how they should best be performed.[41] He was strongly influenced by the innovations in "stagecraft", now called stage direction, by the playwrights James Planché and especially Tom Robertson.[27] Gilbert attended rehearsals directed by Robertson to learn this art first-hand from the older director, and he began to apply it in some of his earliest plays.[42] He sought realism in acting, settings, costumes, and movement, if not in content of his plays (although he did write a romantic comedy in the "naturalist" style, as a tribute to Robertson, Sweethearts). He shunned self-conscious interaction with the audience, and insisted on a style of portrayal in which characters were never aware of their own absurdity, but were coherent internal wholes.[43]

In Gilbert's 1874 burlesque, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, the character Hamlet, in his speech to the players, sums up Gilbert's theory of comic acting: "I hold that there is no such antick fellow as your bombastical hero who doth so earnestly spout forth his folly as to make his hearers believe that he is unconscious of all incongruity".[44] Robertson "introduced Gilbert both to the revolutionary notion of disciplined rehearsals and to mise-en-scène or unity of style in the whole presentation – direction, design, music, acting."[35] Like Robertson, Gilbert demanded discipline in his actors. He required that his actors know their words perfectly, enunciate them clearly and obey his stage directions, ideas new to many actors of the day.[45] A major innovation was the replacement of the star actor with the disciplined ensemble, "raising the director to a new position of dominance" in the theatre.[46] "That Gilbert was a good director is not in doubt. He was able to extract from his actors natural, clear performances, which served the Gilbertian requirements of outrageousness delivered straight."[35]

Gilbert prepared meticulously for each new work, making models of the stage, actors and set pieces, and designing every action and bit of business in advance.[47] He would not work with actors who challenged his authority.[48] George Grossmith wrote that, at least sometime, "Mr. Gilbert is a perfect autocrat, insisting that his words should be delivered, even to an inflection of the voice, as he dictates. He will stand on the stage beside the actor or actress, and repeat the words with appropriate action over and over again, until they are delivered as he desires them to be."[49] Even during long runs and revivals, Gilbert closely supervised the performances of his plays, making sure that the actors did not make unauthorised additions, deletions or paraphrases.[50][51][52] Gilbert was famous for demonstrating the action himself, even as he grew older.[n 8] Gilbert himself went on stage occasionally, including several performances as the Associate in Trial by Jury, as substitute for the injured Kyrle Bellew in a charity matinee of Broken Hearts, and in charity matinees of his one-act plays, such as King Claudius in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.[54][55]

Collaboration with Sullivan

First collaborations amidst other works

In 1871, John Hollingshead commissioned Gilbert to work with Sullivan on a holiday piece for Christmas, Thespis, or The Gods Grown Old, at the Gaiety Theatre. Thespis outran five of its nine competitors for the 1871 holiday season, and its run was extended beyond the length of a normal run at the Gaiety,[56] However, nothing more came of it at that point, and Gilbert and Sullivan went their separate ways. Gilbert worked again with Clay on Happy Arcadia (1872), and with Alfred Cellier on Topsyturveydom (1874), as well as writing several farces, operetta libretti, extravaganzas, fairy comedies, adaptations from novels, translations from the French, and the dramas described above. Also in 1874, he published his last contribution for Fun magazine ("Rosencrantz and Guildenstern"), after a gap of three years, then resigned due to disapproval of the new owner's other publishing interests.[57]

It would be nearly four years after Thespis was produced before the two men worked together again. In 1868, Gilbert had published a short comic sketch in Fun magazine titled "Trial by Jury: An Operetta". In 1873, Gilbert was asked by the theatrical manager, Carl Rosa, to write a work for his planned 1874 season. Gilbert expanded Trial into a one-act libretto. However, Rosa's wife Euphrosyne Parepa-Rosa, a childhood friend of Gilbert's, died after an illness in 1874 and Rosa dropped the project.[58] Later in 1874 Gilbert offered the libretto to Richard D'Oyly Carte, but Carte could not use the piece at that time. By early 1875, Carte was managing the Royalty Theatre, and he needed a short opera to play as an afterpiece to Offenbach's La Périchole. He contacted Gilbert, asked about the piece, and suggested Sullivan to set the work. Sullivan was enthusiastic, and Trial by Jury was composed in a matter of weeks. The little piece was a runaway hit, outlasting the run of La Périchole and being revived at another theatre.[59][n 9]

Gilbert continued his quest to gain respect in and respectability for his profession. One thing that may have been holding dramatists back from respectability was that plays were not published in a form suitable for a "gentleman's library", as, at the time, they were generally cheaply and unattractively published for the use of actors rather than the home reader. To help rectify this, at least for himself, Gilbert arranged in late 1875 for publishers Chatto and Windus to print a volume of his plays in a format designed to appeal to the general reader, with an attractive binding and clear type, containing Gilbert's most respectable plays, including his most serious works, but mischievously capped off with Trial by Jury.[61]

After the success of Trial by Jury, there were discussions towards reviving Thespis, but Gilbert and Sullivan were not able to agree on terms with Carte and his backers. The score to Thespis was never published, and most of the music is now lost. It took some time for Carte to gather funds for another Gilbert and Sullivan opera, and in this gap Gilbert produced several works including Tom Cobb (1875), Eyes and No Eyes (1875, his last German Reed Entertainment), and Princess Toto (1876), his last and most ambitious work with Clay, a three-act comic opera with full orchestra, as opposed to the shorter works for much reduced accompaniment that came before. Gilbert also wrote two serious works during this time, Broken Hearts (1875) and Dan'l Druce, Blacksmith (1876).[28]

Also during this period, Gilbert wrote, Engaged (1877), which inspired Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest. Engaged is a parody of romantic drama written in the "topsy-turvy" satiric style of many of Gilbert's Bab Ballads and the Savoy Operas—with one character pledging his love, in the most poetic and romantic language, to every single woman in the play. The story portrays some "innocent" Scottish rustics making a living by throwing trains off the lines and then charging the passengers for services and, in parallel, romance being gladly thrown over in favour of monetary gain. A New York Times reviewer wrote in 1879, "Mr Gilbert, in his best work, has always shown a tendency to present improbabilities from a probable point of view, and in one sense, therefore, he can lay claim to originality; fortunately this merit in his case is supported by a really poetic imagination. In [Engaged] the author gives full swing to his humor, and the result, although exceedingly ephemeral, is a very amusing combination of characters – or caricatures – and mock-heroic incidents."[62] Engaged is still performed today, by both professional and amateur companies.[63][64][65][66][n 10]

Peak collaborative years

Carte finally assembled a syndicate in 1877 and formed the Comedy Opera Company to launch a series of original English comic operas, beginning with a third collaboration between Gilbert and Sullivan, The Sorcerer, in November 1877. This work was a modest success,[67] and H.M.S. Pinafore followed in May 1878. Despite a slow start, mainly due to a scorching summer, Pinafore became a red-hot favourite by autumn. After a dispute with Carte over the division of profits, the other Comedy Opera Company partners hired thugs to storm the theatre one night to steal the sets and costumes, intending to mount a rival production. The attempt was repelled by stagehands and others at the theatre loyal to Carte, and Carte continued as sole impresario of the newly renamed D'Oyly Carte Opera Company.[68] Indeed, Pinafore was so successful that over a hundred unauthorised productions sprang up in America alone. Gilbert, Sullivan and Carte tried for many years to control the American performance copyrights over their operas, without success.[69]

For the next decade, the Savoy Operas (as the series came to be known, after the theatre Carte later built to house them) were Gilbert's principal activity. The successful comic operas with Sullivan continued to appear every year or two, several of them being among the longest-running productions up to that point in the history of the musical stage.[70][n 11] After Pinafore came The Pirates of Penzance (1879), Patience (1881), Iolanthe (1882), Princess Ida (1884, based on Gilbert's earlier farce, The Princess), The Mikado (1885), Ruddigore (1887), The Yeomen of the Guard (1888) and The Gondoliers (1889). Gilbert not only directed and oversaw all aspects of production for these works, but he actually designed the costumes himself for Patience, Iolanthe, Princess Ida, and Ruddigore.[71] He insisted on precise and authentic sets and costumes, which provided a foundation to ground and focus his absurd characters and situations.[72]

During this time, Gilbert and Sullivan also collaborated on one other major work, the oratorio The Martyr of Antioch, premiered at the Leeds music festival in October 1880. Gilbert arranged the original epic poem by Henry Hart Milman into a libretto suitable for the music, and it contains some original work. During this period, also, Gilbert occasionally wrote plays to be performed elsewhere–both serious dramas (for example The Ne'er-Do-Weel, 1878; and Gretchen, 1879) and humorous works (for example Foggerty's Fairy, 1881). However, he no longer needed to turn out multiple plays each year, as he had done before. Indeed, during the more than nine years that separated The Pirates of Penzance and The Gondoliers, he wrote just three plays outside of the partnership with Sullivan.[28] Only one of these works, Comedy and Tragedy, proved successful.[73][74] Although Comedy and Tragedy had a short run due to the lead actress refusing to act during Holy Week, the play was revived regularly. With respect to Brantinghame Hall, Stedman writes, "It was a failure, the worst failure of Gilbert's career."[75]

In 1878, Gilbert realised a lifelong dream to play Harlequin, which he did at the Gaiety Theatre as part of an amateur charity production of The Forty Thieves, partly written by himself. Gilbert trained for Harlequin's stylised dancing with his friend John D'Auban, who had arranged the dances for some of his plays and would choreograph most of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas.[76][77] Producer John Hollingshead later remembered, "the gem of the performance was the grimly earnest and determined Harlequin of W. S. Gilbert. It gave me an idea of what Oliver Cromwell would have made of the character."[78] Another member of the cast recalled that Gilbert was tirelessly enthusiastic about the piece and often invited the cast to his home for dinner extra rehearsals. "A pleasanter, more genial, or agreeable companion than he was it would have been difficult, if not impossible, to find."[79] In 1882, Gilbert had a telephone installed in his home and at the prompt desk at the Savoy Theatre, so that he could monitor performances and rehearsals from his home study. Gilbert had referred to the new technology in Pinafore in 1878, only two years after the device was invented and before London even had telephone service.[80]

Carpet quarrel and end of the collaboration

Gilbert's working relationship with Sullivan sometimes became strained, especially during their later operas, partly because each man saw himself as subjugating his work to the other's, and partly due to their opposing personalities. Gilbert was often confrontational and notoriously thin-skinned, though given to acts of extraordinary kindness, while Sullivan eschewed conflict.[81] Gilbert imbued his libretti with "topsy-turvy" situations in which the social order was turned upside down. After a time, these subjects were often at odds with Sullivan's desire for realism and emotional content.[82] In addition, Gilbert's political satire often poked fun at those in the circles of privilege, while Sullivan was eager to socialise among the wealthy and titled people who would become his friends and patrons.[83][n 12]

Throughout their collaboration, Gilbert and Sullivan disagreed several times over the choice of a subject. After both Princess Ida and Ruddigore, which were less successful than the seven other operas from H.M.S. Pinafore to The Gondoliers, Sullivan asked to leave the partnership, saying that he found Gilbert's plots repetitive and that the operas were not artistically satisfying to him. While the two artists worked out their differences, Carte kept the Savoy open with revivals of their earlier works. On each occasion, after a few months' pause, Gilbert responded with a libretto that met Sullivan's objections, and the partnership continued successfully.[81]

In April 1890, during the run of The Gondoliers, however, Gilbert challenged Carte over the expenses of the production. Among other items to which Gilbert objected, Carte had charged the cost of a new carpet for the Savoy Theatre lobby to the partnership.[85] Gilbert believed that this was a maintenance expense that should be charged to Carte alone. Gilbert confronted Carte, who refused to reconsider the accounts. Gilbert stormed out and wrote to Sullivan that "I left him with the remark that it was a mistake to kick down the ladder by which he had risen".[81] Helen Carte wrote that Gilbert had addressed Carte "in a way that I should not have thought you would have used to an offending menial."[86] The scholar Andrew Crowther has commented:

After all, the carpet was only one of a number of disputed items, and the real issue lay not in the mere money value of these things, but in whether Carte could be trusted with the financial affairs of Gilbert and Sullivan. Gilbert contended that Carte had at best made a series of serious blunders in the accounts, and at worst deliberately attempted to swindle the others. It is not easy to settle the rights and wrongs of the issue at this distance, but it does seem fairly clear that there was something very wrong with the accounts at this time. Gilbert wrote to Sullivan on 28 May 1891, a year after the end of the "Quarrel", that Carte had admitted "an unintentional overcharge of nearly £1,000 in the electric lighting accounts alone."[81]

Gilbert brought suit, and after The Gondoliers closed in 1891, he withdrew the performance rights to his libretti, vowing to write no more operas for the Savoy.[87] Gilbert next wrote The Mountebanks with Alfred Cellier and the flop Haste to the Wedding with George Grossmith,[28] and Sullivan wrote Haddon Hall with Sydney Grundy. Gilbert eventually won the lawsuit and felt vindicated, but his actions and statements had been hurtful to his partners. Nevertheless, the partnership had been so profitable that, after the financial failure of the Royal English Opera House, Carte and his wife sought to reunite the author and composer.[87]

In 1891, after many failed attempts at reconciliation by the pair, Tom Chappell, the music publisher responsible for printing the Gilbert and Sullivan operas, stepped in to mediate between two of his most profitable artists, and within two weeks had succeeded.[88] Two more operas resulted: Utopia, Limited (1893) and The Grand Duke (1896). Gilbert also offered a third libretto to Sullivan (His Excellency, 1894), but Gilbert's insistence on casting Nancy McIntosh, his protégée from Utopia, led to Sullivan's refusal.[89] Utopia, concerning an attempt to "anglicise" a south Pacific island kingdom, was only a modest success, and The Grand Duke, in which a theatrical troupe, by means of a "statutory duel" and a conspiracy, takes political control of a grand duchy, was an outright failure. After that, the partnership ended for good.[90] Sullivan continued to compose comic opera with other librettists but died four years later. In 1904, Gilbert would write, "... Savoy opera was snuffed out by the deplorable death of my distinguished collaborator, Sir Arthur Sullivan. When that event occurred, I saw no one with whom I felt that I could work with satisfaction and success, and so I discontinued to write libretti."[91]

Later years

Gilbert built the Garrick Theatre in 1889.[92] The Gilberts moved to Grim's Dyke in Harrow in 1890, which he purchased from Robert Heriot, to whom the artist Frederick Goodall had sold the property in 1880.[93] In 1891, Gilbert was appointed Justice of the Peace for Middlesex.[94] After casting Nancy McIntosh in Utopia, Limited, he and his wife developed an affection for her, and she eventually gained the status of an unofficially adopted daughter, moving to Grim's Dyke to live with them. She continued living there, even after Gilbert died, until Lady Gilbert's death in 1936.[95] A statue of Charles II, carved by Danish sculptor Caius Gabriel Cibber in 1681, was moved in 1875 from Soho Square to an island in the lake at Grim's Dyke, where it remained when Gilbert purchased the property.[96] On Lady Gilbert's direction, it was restored to Soho Square in 1938.[97]

Although Gilbert announced a retirement from the theatre after the short run of his last work with Sullivan, The Grand Duke (1896) and the poor reception of his 1897 play The Fortune Hunter, he produced at least three more plays over the last dozen years of his life, including an unsuccessful opera, Fallen Fairies (1909), with Edward German.[98] Gilbert also continued to supervise the various revivals of his works by the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, including its London Repertory seasons in 1906–09.[99] His last play, The Hooligan, produced just four months before his death, is a study of a young condemned thug in a prison cell. Gilbert shows sympathy for his protagonist, the son of a thief who, brought up among thieves, kills his girlfriend. As in some earlier work, the playwright displays "his conviction that nurture rather than nature often accounted for criminal behaviour".[100] The grim and powerful piece became one of Gilbert's most successful serious dramas, and experts conclude that, in those last months of Gilbert's life, he was developing a new style, a "mixture of irony, of social theme, and of grubby realism,"[101] to replace the old "Gilbertianism" of which he had grown weary.[102] In these last years, Gilbert also wrote children's book versions of H.M.S. Pinafore and The Mikado giving, in some cases, backstory that is not found in the librettos.[103][104][105]

Gilbert was knighted on 15 July 1907 in recognition of his contributions to drama.[106] Sullivan had been knighted for his contributions to music almost a quarter of a century earlier, in 1883. Gilbert was, however, the first British writer ever to receive a knighthood for his plays alone – earlier dramatist knights, such as Sir William Davenant and Sir John Vanbrugh, were knighted for political and other services.[107]

On 29 May 1911, Gilbert was about to give a swimming lesson to two young women, Winifred Isabel Emery (1890–1972),[108][109] and 17-year-old Ruby Preece[110][111] in the lake of his home, Grim's Dyke, when Preece got into difficulties and called for help.[85] Gilbert dived in to save her but suffered a heart attack in the middle of the lake and died at the age of 74.[112][113] He was cremated at Golders Green and his ashes buried at the churchyard of St. John's Church, Stanmore.[7] The inscription on Gilbert's memorial on the south wall of the Thames Embankment in London reads: "His Foe was Folly, and his Weapon Wit".[35] There is also a memorial plaque at All Saints' Church, Harrow Weald.

Personality

Gilbert was known for being sometimes prickly. Aware of this general impression, he claimed that "If you give me your attention",[114] the misanthrope's song from Princess Ida, was a satiric self-reference, saying: "I thought it my duty to live up to my reputation."[115] However, many people have defended him, often citing his generosity. Actress May Fortescue recalled,

His kindness was extraordinary. On wet nights and when rehearsals were late and the last buses were gone, he would pay the cab-fares of the girls whether they were pretty or not, instead of letting them trudge home on foot ... He was just as large-hearted when he was poor as when he was rich and successful. For money as money he cared less than nothing. Gilbert was no plaster saint, but he was an ideal friend.[116]

The journalist Frank M. Boyd wrote:

I fancy that seldom was a man more generally given credit for a personality quite other than his own, than was the case with Sir W. S. Gilbert ... Till one actually came to know the man, one shared the opinion held by so many, that he was a gruff, disagreeable person; but nothing could be less true of the really great humorist. He had rather a severe appearance ... and like many other clever people, he had precious little use for fools of either sex, but he was at heart as kindly and lovable a man as you could wish to meet.[117]

Jessie Bond wrote that Gilbert "was quick-tempered, often unreasonable, and he could not bear to be thwarted, but how anyone could call him unamiable I cannot understand."[118] George Grossmith wrote to The Daily Telegraph that, although Gilbert had been described as an autocrat at rehearsals, "That was really only his manner when he was playing the part of stage director at rehearsals. As a matter of fact, he was a generous, kind true gentleman, and I use the word in the purest and original sense."[119]

Aside from his occasional creative disagreements with, and eventual rift from, Sullivan, Gilbert's temper sometimes led to the loss of friendships. For instance, he quarrelled with his old associate C. H. Workman, over the firing of Nancy McIntosh from the production of Fallen Fairies, and with actress Henrietta Hodson. He also saw his friendship with theatre critic Clement Scott turn bitter. However, Gilbert could be extraordinarily kind. During Scott's final illness in 1904, for instance, Gilbert donated to a fund for him, visited nearly every day, and assisted Scott's wife,[120] despite having not been on friendly terms with him for the previous sixteen years.[121] Similarly, Gilbert had written several plays at the behest of comic actor Ned Sothern. However, Sothern died before he could perform the last of these, Foggerty's Fairy. Gilbert purchased the play back from his grateful widow.[122] According to one London society lady:

[Gilbert]'s wit was innate, and his rapier-like retorts slipped out with instantaneous ease. His mind was naturally fastidious and clean; he never asserted himself, never tried to make an effect. He was great-hearted and most understanding, with an underlying poetry of fancy that made him the most delicious companion. They spoke of his quick temper, but that was entirely free from malice or guile. He was soft-hearted as a babe, but there was nothing of the hypocrite about him. What he thought he said on the instant, and though by people of sensitive vanity this might on occasion be resented, to a sensitiveness of a finer kind it was an added link, binding one to a faithful, valued friend.[123]

As the writings about Gilbert by husband and wife Seymour Hicks and Ellaline Terriss (frequent guests at his home) vividly illustrate, Gilbert's relationships with women were generally more successful than his relationships with men.[124][n 13] According to Grossmith, Gilbert "was to those who knew him a courteous and amiable gentleman – a gentleman without veneer."[115] Grossmith and many others wrote of how Gilbert loved to amuse children:

During my dangerous illness, Mr. Gilbert never failed a day to come up and enquire after me ... and kept me in roars of laughter the whole time ... But to see Gilbert at his best, is to see him at one of his juvenile parties. Though he has no children of his own, he loves them, and there is nothing he would not do to please them. I was never so astonished as when on one occasion he put off some of his own friends to come with Mrs. Gilbert to a juvenile party at my own house.[125]

Gilbert's niece Mary Carter confirmed, "he loved children very much and lost no opportunity of making them happy ... [He was] the kindest and most human of uncles."[126] Correspondence between Gilbert and Muriel Barnby, the young daughter of Sir Joseph Barnby, shows his delight in their playful exchange of letters.[127] Grossmith quoted Gilbert as saying, "Deer-stalking would be a very fine sport if only the deer had guns."[119]

Legacy

In 1957, a review in The Times explained "the continued vitality of the Savoy operas" as follows:

[T]hey were never really contemporary in their idiom ... Gilbert and Sullivan's [world], from the first moment was obviously not the audience's world, [it was] an artificial world, with a neatly controlled and shapely precision which has not gone out of fashion – because it was never in fashion in the sense of using the fleeting conventions and ways of thought of contemporary human society ... The neat articulation of incredibilities in Gilbert's plots is perfectly matched by his language ... His dialogue, with its primly mocking formality, satisfies both the ear and the intelligence. His verses show an unequalled and very delicate gift for creating a comic effect by the contrast between poetic form and prosaic thought and wording ... How deliciously [his lines] prick the bubble of sentiment. Gilbert had many imitators, but no equals, at this sort of thing ... [Of] equal importance ... Gilbert's lyrics almost invariably take on extra point and sparkle when set to Sullivan's music ... The two men together remain endlessly and incomparably delightful ... Light, and even trifling, though [the operas] may seem upon grave consideration, they yet have the shapeliness and elegance that can make a trifle into a work of art.[128]

Gilbert's legacy, aside from building the Garrick Theatre and writing the Savoy Operas and other works that are still being performed or in print nearly 150 years after their creation, is felt perhaps most strongly today through his influence on the American and British musical theatre. The innovations in content and form of the works that he and Sullivan developed, and in Gilbert's theories of acting and stage direction, directly influenced the development of the modern musical throughout the 20th century.[129][130] Gilbert's lyrics employ punning, as well as complex internal and two and three-syllable rhyme schemes, and served as a model for such 20th century Broadway librettists and lyricists as P. G. Wodehouse,[131] Cole Porter,[132] Ira Gershwin,[133] Lorenz Hart and Oscar Hammerstein II.[129]

Gilbert's influence on the English language has also been marked, with well-known phrases such as "A policeman's lot is not a happy one", "short, sharp shock", "What never? Well, hardly ever!",[134] and "let the punishment fit the crime" arising from his pen.[n 14] In addition, people continue to write biographies about Gilbert's life and career,[136] and his work is not only performed, but frequently parodied, pastiched, quoted and imitated in comedy routines, film, television and other popular media.[129][137]

Ian Bradley, in connection with the 100th anniversary of Gilbert's death in 2011 wrote:

There has been much discussion about Gilbert's proper place in British literary and dramatic history. Was he essentially a writer of burlesque, a satirist, or, as some have argued, the forerunner of the theatre of the absurd? ... Perhaps he stands most clearly in that distinctively English satirical tradition which stretches back to Jonathan Swift. ... Its leading exponents lampoon and send up the major institutions and public figures of the day, wielding the weapon of grave and temperate irony with devastating effect, while themselves remaining firmly within the Establishment and displaying a deep underlying affection for the objects of their often merciless attacks. It is a combination that remains a continuing enigma.[100]

See also

- W. S. Gilbert bibliography

- Cultural influence of Gilbert and Sullivan

- List of W. S. Gilbert dramatic works

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- ^ He first joined the 5th West Yorkshire Militia, and later the Royal Aberdeenshire Highlanders. On leaving the Militia, Gilbert received an honorary promotion to Major.[13]

- ^ See also the introduction to Gilbert, W. S. (1908), The Bab Ballads, etc., which details the history of the collections it was drawn from.

- ^ See also Tom Robertson's play Society, which fictionalised the evenings in Evans's café in one scene.[18]

- ^ David Eden (in Gilbert and Sullivan: The Creative Conflict 1986) and Andrew Crowther both speculate that the play was written in collaboration with Gilbert's father.[21]

- ^ The full quote refers to Pygmalion and Galatea and reads: "The satire is shrewd, but not profound; the young author is apt to sneer, and he has by no means learned to make the best use of his curiously logical fancy. That he occasionally degrades high and beautiful themes is not surprising. To do so had been the regular proceeding in burlesque, and the age almost expected it; but Gilbert's is not the then usual hearty cockney vulgarity."

- ^ Gilbert gave a speech in 1885 at a dinner to benefit the Dramatic and Musical Sick Fund, which is reprinted in The Era, 21 February 1885, p. 14, in which he said: "In ... the dress circle on the rare occasion of the first performance of an original English play sits a young lady of fifteen. She is a very charming girl – gentle, modest, sensitive – carefully educated and delicately nurtured ... an excellent specimen of a well-bred young English gentlewoman; and it is with reference to its suitability to the eyes and ears of this young lady that the moral fitness of every original English play is gauged on the occasion of its production. It must contain no allusions that cannot be fully and satisfactorily explained to this young lady; it must contain no incident, no dialogue, that can, by any chance, summon a blush to this young lady's innocent face. ... I happen to know that, on no account whatever, would she be permitted to be present at a première of M. Victorien Sardou or M. Alexandre Dumas. ... the dramatists of France can only ring out threadbare variations of that dirty old theme – the cheated husband, the faithless wife, and the triumphant lover."

- ^ This rehearsal was probably for a second run of Ages Ago in 1870.

- ^ In his short story, A Stage Play Gilbert describes the effect of these demonstrations: "... when he endeavours to show what he wants his actors to do, he makes himself rather ridiculous, and there is a good deal of tittering at the wings; but he contrives, nevertheless, to make himself understood ..."[53] See also Stedman (1996), p. 325; and Hicks, Seymour and Terriss, Ellaline. Views of W. S. Gilbert, reprinted at Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, accessed 22 July 2016

- ^ Richard Traubner quotes Sullivan's recollection of Gilbert reading the libretto of Trial by Jury to him: "As soon as he had come to the last word he closed up the manuscript violently, apparently unconscious of the fact that he had achieved his purpose so far as I was concerned, in as much as I was screaming with laughter the whole time."[60]

- ^ See also Feingold, Michael, "Engaging the Past", The Village Voice, 27 April 2004: "Wilde pillaged this piece for ideas."

- ^ Pinafore, Patience and The Mikado each held the position of second longest-running musical theatre production in history for a time (after adjusting Pinafore's initial run down to 571 performances), and The Gondoliers was not far behind.[70]

- ^ Stedman notes some of Sullivan's cuts to Gondoliers to remove anti-monarchist sentiments.[84]

- ^ Crowther (2011) contains numerous examples (including an entire chapter, 18) of Gilbert's friendships with women.

- ^ The last phrase is a satiric take on Cicero's De Legibus, 106 B.C.[135]

References

- ^ Kenrick, John. G&S Story: Part III, accessed 13 October 2006; and Powell, Jim. William S. Gilbert's Wicked Wit for Liberty accessed 13 October 2006.

- ^ Bradley, Chapter 1 and passim.

- ^ Feingold, Michael, "Engaging the Past", The Village Voice, 4 May 2004

- ^ a b c The Cambridge History of English and American Literature, Volume XIII, Chapter VIII, Section 15 (1907–21)

- ^ Gilbert, W. S. Foggerty's Fairy and Other Tales (1890), pp. 158–59.

- ^ How, Harry. Illustrated Interviews No. IV. – Mr. W. S. Gilbert, Strand Magazine, vol. 2, October 1891, pp. 330–341, via the Gilbert and Sullivan Archive

- ^ a b c d Stedman, Jane W. "Gilbert, Sir William Schwenck (1836–1911)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004, online edition, May 2008, accessed 10 January 2010 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Pearson, pp. 16–17

- ^ Ainger, family tree and pp. 15–19

- ^ Eden, David. Gilbert: Appearance and Reality, p. 44, Sir Arthur Sullivan Society (2003)

- ^ Morrison, Robert, "The Controversy Surrounding Gilbert's Last Opera", The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 2 August 2011, accessed 21 July 2016

- ^ Pearson, p. 16.

- ^ Stedman (1996) p. 157 and Ainger, p. 154

- ^ Gilbert, W. S. ed. Peter Haining – Introduction

- ^ Stedman, Jane W. W. S. Gilbert's Theatrical Criticism. London: The Society for Theatre Research, 2000. ISBN 0-85430-068-6

- ^ Stedman (1996), pp. 26–29.

- ^ Stedman (1996), pp. 16–18.

- ^ Robertson, Tom. Society, Act 2, Scene 1

- ^ Ainger, p. 52

- ^ Ainger, p. 148 and Stedman (1996), pp. 318–20. See also Bond, Jessie. Reminiscences, Chapter 16 and McIntosh, Nancy. "The Late Sir W. S. Gilbert's Pets" in the W. S. Gilbert Society Journal, Brian Jones, ed. Vol. 2 No. 18: Winter 2005 (reprinted from Country Life, 3 June 1911), pp. 548–56

- ^ Crowther (2011), p. 45

- ^ Stedman (1996), pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b Gilbert, W. S. La Vivandière, or, True to the Corps! (a burlesque of Donizetti's The Daughter of the Regiment)

- ^ Stedman (1996), p. 62

- ^ Goldberg (1931), p. xvii

- ^ Crowther, Andrew. Introduction to script of "An Old Score", reprinted at the Haddon Hall website Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 21 July 2016

- ^ a b c d Bond, Jessie, Reminiscences, Introduction.

- ^ a b c d List of Gilbert's Plays at the Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 26 May 2009

- ^ Crowther (2011), pp. 82–83

- ^ Stedman (1996), pp. 69–80.

- ^ a b Crowther, Andrew, "Ages Ago – Early Days", The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 23 August 2011, accessed 21 July 2016

- ^ Crowther (2011), p. 84

- ^ Smith, J. Donald, W. S. Gilbert's Operas for the German Reeds

- ^ Crowther (2000), p. 35. See also Gilbert's play, Topsyturveydom.

- ^ a b c d Leigh, Mike. "True anarchists", The Guardian, 3 November 2006

- ^ "Miss Anderson as Galatea", The New-York Times, 1883 January 23 32(9791): 5, col. 3 Amusements Downloaded 15 October 2006.

- ^ Wren, p. 13.

- ^ Rees, Terence. "The Happy Land: its true and remarkable history" in W. S. Gilbert Society Journal vol. 1, no. 8 (1994), pp. 228–37

- ^ Crowther, Andrew. The Realm of Joy: Synopsis, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 2 February 1997, accessed 21 July 2016

- ^ Crowther, Andrew. "Charity: Synopsis", The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 29 November 2009, accessed 21 July 2016

- ^ Stedman (1996), p. 39

- ^ Crowther (2011), p. 74

- ^ Cox-Ife, passim. See also Gilbert, W. S., "A Stage Play" and Bond, Jessie, Reminiscences, Introduction.

- ^ Gilbert, W. S. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, Tableau III, 1874

- ^ Cox-Ife, foreword

- ^ Stedman, Jane W. "General Utility: Victorian Author-Actors from Knowles to Pinero", Educational Theatre Journal, Vol. 24, No. 3, October 1972, pp. 289–301, The Johns Hopkins University Press

- ^ Archer, William. "Mr. W. S. Gilbert", Real Conversations, W. Heinemann (1904), pp. 129–30

- ^ Vorder Bruegge, Andrew (October 2002). "W. S. Gilbert: Antiquarian Authenticity and Artistic Autocracy". Boise, Idaho: Winthrop University. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011.

- ^ Grossmith, George. A Society Clown – via Gilbert and Sullivan Archive.

- ^ Stedman (1996), p. 269 (quoting a 30 April 1890 letter from Gilbert to D'Oyly Carte)

- ^ Gilbert, W. S., A Stage Play

- ^ Bond, Jessie,Reminiscences, Chapter 4

- ^ Gilbert, W. S.. A Stage Play.

- ^ Morrison, Robert. Editorial Notes to Henry Lytton's book, The Secrets of a Savoyard at the Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 19 July 2004, accessed 4 January 2021

- ^ Jennett, Norman E. "Behind the Footlights: Mrs. Alec-Tweedle", New York Herald, 1 October 1904, accessed 1 November 2018

- ^ Walters, Michael. "Thespis: a reply", W. S. Gilbert Society Journal, Vol. 4, part 3, Issue 29. Summer 2011.

- ^ Jones, John Bush, "W. S. Gilbert's Contributions to Fun, 1865–1874", published in the Bulletin of the New York Public Library, vol 73 (April 1969), pp. 253–66

- ^ Stedman, p. 121

- ^ Walbrook, H. M. (1922), Gilbert and Sullivan Opera, a History and Comment (Chapter 3).

- ^ Traubner, Richard. Operetta: A Theatrical History, p. 153, Taylor & Francis (2003) ISBN 0-203-50902-1

- ^ Gilbert (1875), passim

- ^ "Dramatic and Musical", The New York Times, 18 February 1879, p. 5 (subscription required)

- ^ Corry, John. "Stage: W. S. Gilbert's Engaged", The New York Times, 30 April 1981

- ^ Spencer, Charles. "W S Gilbert's original cynicism", The Daily Telegraph, 4 December 2002

- ^ Gardner, Lyn, "Engaged", The Guardian, 2 December 2002

- ^ Nestruck, J. Kelly. "Shaw Festival's Engaged is W. S. Gilbert alone, and still outrageously funny ", The Globe and Mail, 28 June 2016.

- ^ Ainger, pp. 147–52

- ^ Bond, Jessie, Chapter 4.

- ^ Rosen, Zvi S. "The Twilight of the Opera Pirates: A Prehistory of the Right of Public Performance for Musical Compositions", accessed 26 May 2009

- ^ a b List of longest running London shows through 1920.

- ^ Profile of W. S. Gilbert, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 26 May 2009

- ^ Stedman (1996), p. 155

- ^ Foggerty's Fairy: Crowther, Andrew. "Foggerty's Failure", The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 29 August 2011, accessed 22 July 2016

- ^ Comedy and Tragedy: Stedman (1996), pp. 204–05.

- ^ Stedman (1996), p. 254

- ^ "Mr. D'Auban's 'Startrap' Jumps". The Times, 17 April 1922, p. 17

- ^ Biographical file for John D'Auban, list of productions and theatres, The Theatre Museum, London (2009)

- ^ Hollingshead, John. My Lifetime, vol 2, p. 124 (1895) S. Low, Marston: London

- ^ Elliot, William Gerald. "The Amateur Pantomime of 1878", Amateur Clubs and Actors, Chapter VI, pp. 122–23 (1898) London: E. Arnold

- ^ Bradley, p. 176.

- ^ a b c d Crowther, Andrew, "The Carpet Quarrel Explained", The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 28 June 1997, accessed 22 July 2016

- ^ See, e.g. Ainger, p. 288, or Wolfson, p. 3

- ^ See, e.g. Jacobs (1992); Crowther (2011); and Bond, Jessie. Chapter 16, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 22 July 2016.

- ^ Stedman (1996), pp. 264–65

- ^ a b Ford, Tom. "G&S: the Lennon/McCartney of the 19th century" Archived 15 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Limelight Magazine, Haymarket Media Ltd., 8 June 2011

- ^ Stedman, p. 270

- ^ a b Shepherd, Marc. "Introduction: Historical Context", The Grand Duke, p. vii, New York: Oakapple Press, 2009. Linked at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 7 July 2009.

- ^ Wolfson, p. 7.

- ^ Wolfson, pp. 61–65.

- ^ Wolfson, passim

- ^ Letter to the Editor, The Times, 12 March 1904; p. 9

- ^ Stedman (1996) p. 251.

- ^ Stedman (1996), p. 278.

- ^ Stedman (1996) p. 281.

- ^ Who Was Who in The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company: Nancy McIntosh at the Gilbert and Sullivan Archive.

- ^ "Soho Square Area: Portland Estate: Soho Square Garden" in Survey of London volumes 33 and 34 (1966) St Anne Soho, pp. 51–53. Date accessed: 12 January 2008.

- ^ Charles II Statue Archived 5 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine at LondonRemembers.

- ^ Wolfson, pp. 102–03.

- ^ Wolfson, p. 102.

- ^ a b Bradley, Ian. "W. S. Gilbert: He was an Englishman". History Today, Vol. 61, Issue 5, 2011

- ^ Stedman (1996), p. 343.

- ^ Crowther, Andrew. Notes on The Hooligan, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 31 July 2011, accessed 22 July 2016

- ^ Stedman (1996), p. 331

- ^ Gilbert, W. S. The Pinafore Picture Book, London: George Bell and Sons (1908)

- ^ Gilbert, W. S. The Story of The Mikado, London: Daniel O'Connor (1921)

- ^ Ainger, pp. 417–18

- ^ Stedman (1996), p. 328.

- ^ Biography of David Gascoyne, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed 2 June 2011

- ^ Dark, Sidney and Rowland Grey. W. S. Gilbert: His Life and Letters, Methuen & Co Ltd, London (1923) p. 222

- ^ "Spencer, Sir Stanley", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed 2 June 2011; see also Preece Family History and One Name Study (1894–1895), accessed 2 June 2011

- ^ Elliott, Vicky. "Lives Laid Bare – The second wife of the British painter Stanley Spencer ..." SF Gate, San Francisco Chronicle, 19 July 1998, accessed 2 June 2011

- ^ Stedman (1996), p. 346

- ^ Goodman, Andrew. Grim's Dyke: A Short History of the House and Its Owners, Glittering Prizes, pp. 17–18 ISBN 978-1-85811-550-4

- ^ Howarth, Paul and Feldman, A. "If you give me your attention", Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 29 May 2011

- ^ a b Grossmith, George. "Recollections of Sir W. S. Gilbert", The Bookman, vol. 40, no. 238, July 1911, p. 162

- ^ Dark and Grey, pp. 157–58

- ^ Boyd, Frank M. A Pelican's Tale, Fifty Years of London and Elsewhere, p. 195, London: Herbert Jenkins Ltd (1919)

- ^ Bond, Jessie, Chapter 16

- ^ a b George Grossmith's tribute to Gilbert in The Daily Telegraph, 7 June 1911

- ^ Scott, Mrs. Clement, Old Days in Bohemian London (c.1910). New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company. pp. 71–72

- ^ See Stedman (1996), pp. 254–56, 323–24

- ^ Ainger, pp. 193–94.

- ^ Anonymous 1871–1935, p. 238, London: John Murray (1936)

- ^ Hicks, Seymour and Terriss, Ellaline Views of W. S. Gilbert, reproduced at Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, accessed 22 July 2016

- ^ Grossmith, p. 190

- ^ Carter, Mary. Letter to the editor of The Daily Telegraph, 6 January 1956

- ^ Barnby, Muriel. "My Letters from Gilbert and Sullivan", Strand Magazine, vol. 72, December. 1926, pp. 642–646

- ^ "The Lasting Charm of Gilbert and Sullivan: Operas of an Artificial World", The Times, 14 February 1957, p. 5

- ^ a b c Downs, Peter. "Actors Cast Away Cares". Hartford Courant, 18 October 2006. Available for a fee at courant.com archives.

- ^ Cox-Ife, passim

- ^ PG Wodehouse (1881–1975) guardian.co.uk, accessed 21 May 2007.

- ^ Millstein, Gilbert. "Words Anent Music by Cole Porter", The New York Times, 20 February 1955; and Lesson 35 – Cole Porter: You're the Top PBS.org, American Masters for Teachers, accessed 21 May 2007.

- ^ Furia, Philip.Ira Gershwin: The Art of a Lyricist, Oxford University Press, accessed 21 May 2007

- ^ Lawrence, Arthur H. "An illustrated interview with Sir Arthur Sullivan", Part 3, from The Strand Magazine, Vol. xiv, No.84 (December 1897)

- ^ Green, Edward. "Ballads, songs and speeches", BBC, 20 September 2004, accessed 16 October 2006.

- ^ e.g., Stedman (1996), Ainger (2002) and Crowther (2011)

- ^ Bradley (2005), Chapter 1

Sources

- Ainger, Michael (2002). Gilbert and Sullivan – A Dual Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514769-8.

- Bond, Jessie (1930). The Life and Reminiscences of Jessie Bond, the Old Savoyard (as told to Ethel MacGeorge). London: John Lane, The Bodley Head. OCLC 1941674.

- Bradley, Ian (2005). Oh Joy! Oh Rapture! The Enduring Phenomenon of Gilbert and Sullivan. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516700-9.

- Cox-Ife, William (1978). W. S. Gilbert: Stage Director. London: Dobson. ISBN 978-0-234-77206-5.

- Crowther, Andrew (2000). Contradiction Contradicted – The Plays of W. S. Gilbert. Associated University Presses. ISBN 978-0-8386-3839-2.

- Crowther, Andrew (2011). Gilbert of Gilbert & Sullivan: his Life and Character. London: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5589-1.

- Dark, Sidney; Rowland Grey (1923). W. S. Gilbert: His Life and Letters. London: Methuen. OCLC 3389751.

- Gilbert, W. S. (1908). The Bab Ballads, with which are included Songs of a Savoyard (6th ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 3160380. (A collection of material from several books published previously.)

- Gilbert, W. S. (1892). Foggerty's Fairy and Other Tales. London: George Routledge and Sons. OCLC 3873303.

- Gilbert, W. S. (1985). Peter Haining (ed.). The Lost Stories of W. S. Gilbert. London and New York: Robson Books. ISBN 978-0-86051-337-7. (Contains mostly stories from Foggerty's Fairy and Other Tales.)

- Gilbert, W. S. (1911). Original Plays: First Series. London: Chatto and Windus. OCLC 436914141.

- Gilbert, W. S. (1908). Original Plays: Second Series. London: Chatto and Windus. OCLC 19348369.

- Gilbert, W. S (1969). Terence Rees (ed.). The Realm of Joy: Being a Free and Easy Version of "Le roi candaule" by Henri Meilhac. London: Terence Rees. ISBN 978-0-9500108-1-6.

- Gilbert, W. S. (1931). Isaac Goldberg (ed.). New and original extravaganzas, by W. S. Gilbert, Esq., as first produced at the London playhouse. Boston: Luce. OCLC 503311131.

- Grossmith, George (1888). A Society Clown: Reminiscences. Bristol and London: Arrowsmith. OCLC 8060335.

- Jacobs, Arthur (1992). Arthur Sullivan – A Victorian Musician (Second ed.). Portland, OR: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-0-931340-51-2.

- Pearson, Hesketh (1957). Gilbert: His Life and Strife. London: Methuen. OCLC 771800508.

- Stedman, Jane W. (1996). W. S. Gilbert, A Classic Victorian & His Theatre. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816174-5.

- Stedman, Jane W. (2000). W. S. Gilbert's Theatrical Criticism. London: The Society for Theatre Research. ISBN 978-0-85430-068-6.

- Scott, Mrs Clement (1918). Old Days in Bohemian London. New York: Frederick A. Stokes. OCLC 1454858.

- Wolfson, John (1976). Final Curtain: The Last Gilbert and Sullivan Operas. London: Chappell. ISBN 978-0-903443-12-8.

- Wren, Gayden (2006). A Most Ingenious Paradox: The Art of Gilbert & Sullivan. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514514-4.

Further reading

- Bradley, Ian (1996). The Complete Annotated Gilbert and Sullivan. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816503-3.

- Gilbert, W. S. (1969). Jane W. Stedman (ed.). Gilbert Before Sullivan–Six Comic Plays by W. S. Gilbert. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. OCLC 597003.

- Gilbert, W. S. (2018). Andrew Crowther (ed.). The Triumph of Vice and Other Stories. Alma Classics. ISBN 978-1-84-749754-3.

External links

- Works by W. S. Gilbert at Project Gutenberg

- Works by W. S. Gilbert at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by W. S. Gilbert at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by or about W. S. Gilbert at the Internet Archive

- W. S. Gilbert Society website

- The Life of W. S. Gilbert, by Andrew Crowther

- Interview of Gilbert by Harry How in The Strand Magazine (1891)

- List of Gilbert's works, with links to most of them, and information about them, at The Gilbert & Sullivan Archive

- A Stage Play, by W. S. Gilbert, giving some of his philosophy of the theatre

- Collection of Gilbert prefaces to various plays Archived 1 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Some of Gilbert's short stories

- W. S. Gilbert

- 1836 births

- 1911 deaths

- 19th-century British Army personnel

- 19th-century British civil servants

- 19th-century British short story writers

- 19th-century English dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century English dramatists and playwrights

- 19th-century English lawyers

- 19th-century English poets

- Alumni of King's College London

- British theatre directors

- Deputy Lieutenants of Middlesex

- English illustrators

- English male dramatists and playwrights

- English male poets

- English opera librettists

- Freemasons of the United Grand Lodge of England

- Gilbert and Sullivan

- Knights Bachelor

- Members of the Inner Temple

- People from Pinner

- Victorian poets

- Writers who illustrated their own writing

- Writers from London

- People from the City of Westminster

- British Militia officers

- Military personnel from London

- British Army soldiers