Aglais io

| European peacock | |

|---|---|

| |

| On blackthorn at Otmoor, Oxfordshire, England | |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Family: | Nymphalidae |

| Genus: | Aglais |

| Species: | A. io

|

| Binomial name | |

| Aglais io | |

| Subspecies | |

| Synonyms | |

Aglais io, the European peacock,[3][4][5] or the peacock butterfly, is a colourful butterfly, found in Europe and temperate Asia as far east as Japan. It was formerly classified as the only member of the genus Inachis (the name is derived from Greek mythology, meaning Io, the daughter of Inachus[citation needed]). It should not be confused or classified with the "American peacocks" in the genus Anartia; while belonging to the same family as the European peacock, Nymphalidae, the American peacocks are not close relatives of the Eurasian species. The peacock butterfly is resident in much of its range, often wintering in buildings or trees. It therefore often appears quite early in spring. The peacock butterfly has figured in research in which the role of eyespots as an anti-predator mechanism has been investigated.[6] The peacock is expanding its range[3][7] and is not known to be threatened.[7]

Characteristics

The butterfly has a wingspan of 50 to 55 millimetres (2 to 2+1⁄8 in). The base colour of the wings is a rusty red, and at each wingtip it bears a distinctive, black, blue and yellow eyespot. The underside is a cryptically coloured dark brown or black.

There are two subspecies: A. io caucasica (Jachontov, 1912), found in Azerbaijan, and A. io geisha (Stichel, 1908), found in Japan and the Russian Far East.

-

Dorsal side

-

Ventral side

-

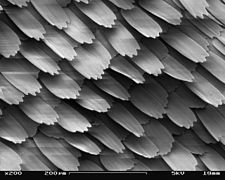

Wing scales

-

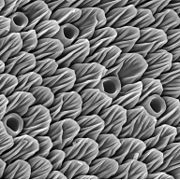

Wing scales at Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

-

Olfactory sensors (scales and holes) on the antenna, under the electron microscope

Natural history

The peacock can be found in woods, fields, meadows, pastures, parks, and gardens, from lowlands up to 2,500 metres (8,200 ft) elevation. It is a relatively common butterfly, seen in many European parks and gardens. The peacock male exhibits territorial behaviour, in many cases territories being selected en route of the females to oviposition sites.[8]

The butterfly hibernates over winter before laying its eggs in early spring, in batches of up to 400 at a time.[3] The olive green eggs are ribbed. They are laid on both the upper parts and the undersides of leaves of nettle plants[9] and hops. The caterpillars hatch after about a week. They are shiny black with six rows of barbed spikes and a series of white dots on each segment. The chrysalis may be either grey, brown or green, and may have a blackish tinge.[9] The caterpillars grow up to 42 millimetres (1+5⁄8 in) in length.

The recorded food plants of the European peacock are stinging nettle (Urtica dioica), hop (Humulus lupulus), and the small nettle (Urtica urens).[3]

The adult butterflies drink nectar from a wide variety of flowering plants, including buddleia, willows, dandelions, wild marjoram, danewort, hemp agrimony, and clover; they also use tree sap and rotten fruits.

Behaviour

Mating system and territorial behaviour

Aglais io employs a monogamous mating system, which means that they only mate with one partner for a period of time.[citation needed] This is due to their life cycle in which females are receptive only during an eclosion period, after overwintering. The pairs only mate once after overwintering, as it is very difficult to find a receptive female after that period.[10] In species where the range of the females is not defensible by a male, the males must defend a single desirable area that females will come through, such as dense food areas, watering holes, or favourable nesting sites. The males then attempt to mate with the females as they are passing through.

Holding a desirable territory increases the male's likelihood of finding a mate and therefore increases his reproductive success. However, each individual needs to weigh the benefits of mating with the costs of defending a territory.[11] Aglais io exhibits this type of territorial behaviour, and must defend a desirable territory from other males. If only one of the males knows the territory well, he will successfully chase off any intruders. On the other hand, if both males are familiar with the territory, there will be a contest between the two to determine which of them stays in the territory. The most desirable sites are those that will increase the male's quota of females. These sites are generally feeding and oviposition sites, which are sought after by females. This territorial behaviour is reinforced by the fact that these sites are all concentrated. If the valuable resources were dispersed, there would be less observable territorial behaviour.[12]

To find mates and defend their territory, Aglais io exhibits perching behaviour. The male butterflies will perch on an object at a specific height where they can observe passing flying objects. Every time they see a passing object of their own species or of a relevant species, they will fly straight towards the object until they are approximately 10 cm away. If they encounter a male, the resident male will chase him off his territory. If the resident male encounters a female, he will pursue her until she lands and mating will occur.[13] The courtship is extended in this species. The male goes through a long chase before the female allows him to mate. He must demonstrate high performance flight.[14]

The monandrous mating system has caused the evolution of a shorter life span in males of this species. In polygynous butterflies, the male's reproductive success is largely dependent on life span. Therefore, the longer a male lives, the more he can reproduce, so he has a higher fitness. Therefore, males tend to live as long as the females. In A. io the synchronous eclosion at the end of winter cause males to only mate once. Their reproductive success is therefore not linked to how long they live, and there is no selective pressure to live longer. Therefore, the life span of males is shorter than the lifespan of the females.[10]

Anti-predator defense mechanisms

Like many other butterflies that hibernate, the peacock butterfly exhibits many anti-predator defence mechanisms against would-be predators. The peacock butterfly's most obvious defense comes from the four large eyespots that it has on its wings. It also uses camouflage and can emit a hissing sound.[15]

The eyespots are brilliantly coloured concentric circles. Avian predators of the butterfly include blue tits, pied flycatchers and other small passerine birds. The first line of defence against these predators for many hibernating butterflies is crypsis, a process in which the butterflies blend into their environment by mimicking a leaf and staying immobile.[16] Some hibernating butterflies such as the peacock have a second line of defence: when attacked, they open their wings and expose their eyespots in an intimidating threat display, which gives the butterfly a much better chance at escaping predators than butterflies that rely solely on leaf mimicry.[16] While the main targets of these anti-predation measures are small passerine birds, even larger birds such as chickens have been shown to react to the stimuli and avoid the butterfly when exposed to eyespots.[17]

Avian predators

Research has shown that avian predators attempting to attack a butterfly hesitate for a much longer time if they encounter butterflies that display their eyespots than if they encounter butterflies whose eyespots are covered. In addition, the predators delay their return to the butterfly if it displays eyespots[17][18] and some predators even flee before attacking the butterfly.[18] By intimidating the predator so that it delays or gives up its attack, the peacock butterfly has a much greater chance of escaping predation.

According to the eye mimicry hypothesis, the eyespots serve an anti-predatory purpose by imitating the eyes of the avian predators' natural enemies.[17] In contrast, the conspicuousness hypothesis posits that rather than recognition of the eyespots as belonging to an enemy, the conspicuous nature of the eyespots, which are typically large and bright, causes a response in the visual system of the predator that leads to avoidance of the butterfly.[19]

In one experiment, observed responses of the avian predators to the eyespots included increased vigilance, a delay in their return to the peacock butterfly, and the production of alarm calls associated with ground-based predators.[17] These responses to the eyespot stimuli lend support to the eye mimicry hypothesis as they indicated that the avian predator sensed that the eyespots belonged to a potential enemy. When faced with avian predators like the blue tit, the peacock butterfly makes a hissing noise as well as threateningly displaying its eyespots. However, it is the eyespots that protect the butterfly the most; peacock butterflies that have had their sound production capability removed still defend themselves extremely well against avian predators if their eyespots are present.[20]

Rodent predators

While hibernating in dark wintering areas, the peacock butterfly frequently encounters rodent predators such as small mice. Against these predators, however, the visual display of eyespots is ineffective due to the darkness of the environment. Instead, these rodent predators show a much stronger adverse reaction to the butterfly when it produces its auditory hissing signal. This indicates that for rodent predators, it is the auditory signal produced by the butterfly that serves as a deterrent.[15]

Etymology

Io is a figure in Greek mythology. She was a priestess of Hera in Argos.

Gallery

-

Underside pattern

-

Eggs

-

Caterpillar

-

Feeding

-

Chrysalis

-

Achromatic form of eyespots

See also

- Anglewing butterflies

- Peacock butterflies (genus Anartia)

- Peacock pansy (Junonia almana)

References

- ^ a b Linnaeus, Carl; Salvius, Lars (1758). Caroli Linnaei...Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (pdf) (in Latin). Holmiae : Impensis Direct. Laurentii Salvii. p. 472. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.542. OCLC 499504699. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ "Aglais io". Global Biodiversity Information Facility.

- ^ a b c d Eeles, Peter. "Peacock - Aglais io". UK Butterflies. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Aglais io, Moths and Butterflies of Europe and North Africa

- ^ The higher classification of Nymphalidae Archived 2009-02-20 at the Wayback Machine, Nymphalidae.net

- ^ Stevens, Martin (2005). "The role of eyespots as anti-predator mechanisms, principally demonstrated in the Lepidoptera". Biological Reviews. 80 (4): 573–588. doi:10.1017/S1464793105006810. PMID 16221330. S2CID 24868603. (Abstract)

- ^ a b "Peacock". A-Z of Butterflies. Butterfly Conservation. Archived from the original on 16 November 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ Price, Peter W. (1997). Insect ecology (3rd (illustrated) ed.). John Wiley. p. 405. ISBN 9780471161844. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ a b Stokoe, W.J. (1966). The Observers Book of Butterflies. The Observer's Books (Fully illustrated ed.). London: Frederick Warne & Co. p. 191.

- ^ a b Wiklund, Christer; Karl Gotthard; Sören Nylin (2003). "Mating system and the evolution of sex-specific mortality rates in two nymphalid butterflies". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 270 (1526): 1823–1828. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2437. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1691446. PMID 12964985.

- ^ Davies, N., Krebs, J., & West, S. (2012). An Introduction to Behavioral Ecology. (4th ed.). West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781444339499.

- ^ R. R. Baker (1972). "Territorial behaviour of the nymphalid butterflies, Aglais urticae (L.) and Inachis io (L.)". Journal of Animal Ecology. 41 (2): 453–469. doi:10.2307/3480. JSTOR 3480.

- ^ Scott, J. A. (1974). "Mate-locating behavior of butterflies". American Midland Naturalist. 91 (1): 103–117. doi:10.2307/2424514. JSTOR 2424514.

- ^ Bergman, Martin; Karl Gotthard; David Berger; Martin Olofsson; Darrell J. Kemp; Christer Wiklund (2007). "Mating success of resident versus non-resident males in a territorial butterfly". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 274 (1618): 1659–1665. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0311. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1914333. PMID 17472909.

- ^ a b Martin Olofsson; Sven Jakobsson; Christer Wiklund (2012). "Auditory Defence in the Peacock Butterfly (Inachis io) against Mice (Apodemus flavicollis and A. sylvaticus)". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 66 (2): 209–15. doi:10.1007/s00265-011-1268-1. S2CID 18172201.

- ^ a b Adrian Vallin; Sven Jakobsson; Johan Lind; Christer Wiklund (2006). "Crypsis versus Intimidation: Anti-Predation Defence in Three Closely Related Butterflies" (PDF). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 59 (3): 455–459. doi:10.1007/s00265-005-0069-9. S2CID 20742464. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-07-12. Retrieved 2016-01-24.

- ^ a b c d Martin Olofsson; Hanne Løvlie; Jessika Tiblin; Sven Jakobsson; Christer Wiklund (2012). "Eyespot Display in the Peacock Butterfly Triggers Antipredator Behaviors in Naïve Adult Fowl". Behavioral Ecology. 24 (1): 305–10. doi:10.1093/beheco/ars167. PMC 3518204. PMID 23243378.

- ^ a b S. Merilaita; A. Vallin; U. Kodandaramaiah; M. Dimitrova; S. Ruuskanen; T. Laaksonen (2011). "Number of Eyespots and Their Intimidating Effect on Naive Predators in the Peacock Butterfly". Behavioral Ecology. 22 (6): 1326–331. doi:10.1093/beheco/arr135.

- ^ M. Stevens; C. J. Hardman; C. L. Stubbins (2008). "Conspicuousness, Not Eye Mimicry, Makes "eyespots" Effective Antipredator Signals". Behavioral Ecology. 19 (3): 525–31. doi:10.1093/beheco/arm162.

- ^ A. Vallin; S. Jakobsson; J. Lind; C. Wiklund (2005). "Prey Survival by Predator Intimidation: An Experimental Study of Peacock Butterfly Defence against Blue Tits". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 272 (1569): 1203–207. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.3034. PMC 1564111. PMID 16024383.

External links

- Peacock (Inachis io) from the [1], UK Butterflies

- HD video of Peacock and Vanessa butterflies

- Peacock page, Aglais io from the Butterfly Conservation

- Inachis io, Arkive

- Inachis io, Learn about Butterflies

- Peacock - Inachis io, Captain's European Butterfly Guide