List of Owenite communities in the United States

This is a list of Owenite communities in the United States which emerged during a short-lived popular boom during the second half of the 1820s. Between 1825 and 1830 more than a dozen such colonies were established in the United States, inspired by the ideas of Robert Owen. All of these met with economic failure and rapid disestablishment within one or a comparatively few years.

The Owenite movement of the 1820s was one of the four primary branches of secular Utopian Socialism in the United States during the 19th century, antedating Fourierism (1843–50), Icarianism (1848–98) and Bellamyism (1889–96).

Background

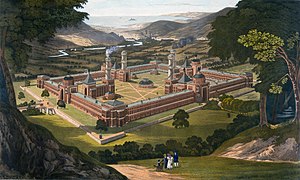

The communitarian ideas of Welsh reformer Robert Owen (1772–1837) were popularized in the United States by his arrival in America in November 1824. Owen had learned that an already established Rappite religious community at Harmony, Indiana was for sale and set sail for America with a view acquiring it from the Harmony Society and thereby making it a model for his collectivist plans.[1] This initial American community of Owen, a tract of 30,000 acres on the Wabash River which included farmland, dwellings, and factories, would be rechristened "New Harmony" and served as the inspiration for the establishment of other Owenite colonies.[2]

The idea of Owenite communities in the United States was boosted by two widely publicized addresses by Owen made before the United States Congress, dated February 25 and March 7, 1825.[3] The assembled audience included President John Quincy Adams, several members of his cabinet, the justices of the Supreme Court of the United States, and a number of other invited luminaries.[4]

Owen was assisted in his development of New Harmony by Philadelphian William Maclure, himself a wealthy philanthropist as well as the leading American geologist of the day.[2] Other leading American intellectuals directly participated in the project, including preeminent zoologist Thomas Say, painter Charles Alexandre Lesueur, visionary pedagogue Francis Neef, and Scottish-born feminist and freethinker Frances "Fanny" Wright, among others.[5]

A brief fad followed seeking the realization of Owen's ideas in practice, resulting in the formation of over a dozen Owenite communities. All of these proved short-lived, whether owing to internal dissension or an inability to generate a surplus producing manufactured goods and agricultural products sufficient to retire debts incurred. By about 1830 the Owenite movement in America had vanished with little trace, the established village of New Harmony having long since converted to operation on an individualistic basis.

List

| Name | Location | Launched | Terminated | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Harmony | New Harmony, Indiana | May 1825 | 1827 | |

| Macluria | New Harmony, Indiana | 1826 | 1827 | Also known as "No. 2." Split group of religious Westerners from New Harmony. |

| Feiba Peveli | New Harmony, Indiana | 1826 | ??? | Also known as "No. 3." Split group of English farmers from New Harmony, which survived the original colony's demise. |

| Blue Spring Community | Monroe County, IN | 1826 | 1827 | Located about 7 miles SW of Bloomington.[6] |

| Forestville Community | Coxsackie, NY | ??? | 1827 | |

| Franklin Community | Haverstraw, NY | 1826 | 1826 | |

| Kendal Community | Massillon, OH | 1826 | 1829 | "Longest life of any Owenite Project."[7] Voted to terminate Jan. 3, 1829.[8] |

| Nashoba Community | Nashoba, TN | 1825 | 1830 | "Emancipation Plantation" conceived by Francis "Fanny" Wright. |

| Wanborough Community | Wanborough, IL | 1826 | ??? | Mentioned in Lockwood (1905) as having been established by May 1826.[9] |

| Yellow Springs Community | Yellow Springs, OH | 1825 | 1825 | Launched in July, terminated end of December 1825. Current location of Antioch College.[10] |

- Source: T.D. Seymour Bassett, "The Secular Utopian Socialists," pp. 160-167 (unless otherwise noted).

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Morris Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States. [1903] Revised Fifth Edition. New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1910; pg. 53.

- ^ a b Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States, pg. 58.

- ^ T.D. Seymour Bassett, "The Secular Utopian Socialists," in Donald Drew Egbert and Stow Persons (eds.), Socialism and American Life: Volume 1. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1952; pg. 162.

- ^ George B. Lockwood with Charles A. Prosser, The New Harmony Movement. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1905; pg. 69.

- ^ Hillquite, History of Socialism in the United States, pg. 59.

- ^ "Aspiring Towards Utopia: Blue Spring Community," Indiana Magazine of History, Sept. 12, 2011.

- ^ Bassett, "The Secular Utopian Socialists," pg. 167.

- ^ Bestor, Backwoods Utopias, pg. 206.

- ^ Lockwood with Prosser, The New Harmony Movement, pg. 144.

- ^ Bestor, Backwoods Utopias, pp. 210-211.

Further reading

- Dawn Bakken, "'A Full Supply of the Necessaries and Comforts of Life': The Constitution of the Owenite Community of Blue Spring, Indiana," Indiana Magazine of History, vol. 107, no. 3 (Sept. 2011), pp. 235–249.

- T.D. Seymour Bassett, "The Secular Utopian Socialists," in Donald Drew Egbert and Stow Persons (eds.), Socialism and American Life: Volume 1. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1952; pp. 153–211.

- Gail Bederman, "Revisiting Nashoba: Slavery, Utopia, and Frances Wright in America, 1818-1826," American Literary History, vol. 17, no. 3 (2005), pp. 438–459.

- Arthur Bestor, Backwoods Utopias: The Sectarian Origins and the Owenite Phase of Communitarian Socialism in America, 1663-1829. [1950] Enlarged 2nd Edition. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1970.

- Frederick A. Bushee, "Communistic Societies in the United States," Political Science Quarterly, vol. 20, no. 4 (Dec. 1905), pp. 625–664. In JSTOR

- Donald F. Carmony and Josephine M. Elliott, New Harmony, Indiana: Robert Owen's Seedbed for Utopia. University of Southern Indiana, 1999.

- John F.C. Harrison, Quest for the New Moral World: Robert Owen and the Owenites in Britain and America. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1969.

- Morris Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States. [1903] Revised Fifth Edition. New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1910.

- William Alfred Hinds, American Communities and Co-operative Colonies, Second Edition. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1908.

- Lloyd Jones, The Life, Times, and Labours of Robert Owen. London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1890.

- Carol A. Kolmerten, Women in Utopia: The Ideology of Gender in the American Owenite Communities. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1990.

- George B. Lockwood, The New Harmony Communities. Marion, IN: Chronicle Co., 1902.

- George B. Lockwood with Charles A. Prosser, The New Harmony Movement. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1905. —Revised edition of The New Harmony Communities.

- Hyman Mariampolsky, The Dilemmas of Utopian Communities: A Study of the Owenite Community at New Harmony, Indiana. PhD dissertation. Purdue University, 1977.

- Edward Royle, Robert Owen and the Commencement of the Millennium: Study of the Harmony Community. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1998.

- Donald E. Pitzer (ed.), Robert Owen's American Legacy: Proceedingsof the Robert Owen Bicentennial Conference. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1972.

- Richard Simons, "A Utopian Failure," Indiana History Bulletin, vol. 18 (Jan. 1941), pp. 98–113. —On Blue Spring Community.

- Renee M. Stowitzky, Searching for Freedom through Utopia: Revisiting Frances Wright's Nashoba. Honors Thesis. Vanderbilt University, 2004.

- William E. Wilson, The Angel and the Serpent: The Story of New Harmony. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1964.

- The New Harmony Gazette. (1825-1828)