Hurricane Greta (1956)

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

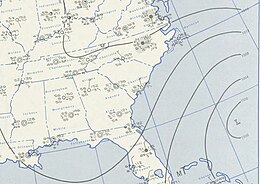

November 2, 1956 weather map, featuring the storm | |

| Formed | October 30, 1956 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | November 6, 1956 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 100 mph (155 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 970 mbar (hPa); 28.64 inHg |

| Fatalities | 1 direct |

| Damage | $3.6 million (1956 USD) |

| Areas affected | Jamaica, Hispaniola, Cuba, The Bahamas, Southeast United States, Turks and Caicos Islands, Puerto Rico, Lesser Antilles |

| Part of the 1956 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Hurricane Greta was an extremely large late-season Atlantic hurricane in the 1956 Atlantic hurricane season. Originating from a tropical depression near Jamaica on October 30, the system initially featured non-tropical characteristics as it tracked northward. By November 2, the system began producing gale-force winds around the low pressure area; however, winds near the center of circulation were calm. By November 3, the system intensified into a tropical storm and was named Greta. Steadily strengthening, Greta attained hurricane intensity on November 4, eventually reaching a peak intensity with 100 mph (155 km/h) winds. Shortly after, Greta began to gradually weaken as it tracked over cooler waters. The storm eventually became extratropical on November 7 over the central Atlantic. Although Greta did not directly impact land as a tropical storm or hurricane, it generated large swells that impacted numerous areas. One person was killed in Puerto Rico and coastal damages from the waves amounted to roughly $3.6 million (1956 USD).

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

Hurricane Greta originated out of a tropical disturbance in the Intertropical Convergence Zone near Jamaica on October 30, 1956. A Navy reconnaissance plane recorded sustained winds of 35 mph (55 km/h) and found an area of low pressure.[1] Around this time, the system was classified as a tropical depression.[2] Although a ship near the system discovered a cold-core circulation—a feature of non-tropical cyclones—it was classified as tropical.[1] By October 31, the depression passed near the western edge of Haiti and later crossed the eastern tip of Cuba before entering the Atlantic Ocean. By the afternoon of November 1, the depression had moved through the central Bahamas and turned towards the northeast.[2]

By this time, the central pressure of the depression had decreased to 998 mbar (hPa; 29.47 inHg) and gale-force winds were recorded over a large area, and the system was upgraded to a tropical storm that morning. The system was compared to that of a Kona low, a large-scale subtropical cyclone that forms near Hawaii. Early on November 2, the storm turned northwest in response to an area of high pressure over the central Atlantic.[1] Later that day, the first scientific mission into a hurricane with two planes took place when two research aircraft flew into Greta. During the day, an Air Force B-50 aircraft and NHRP B-47 high altitude jet flew into the storm.[3] The storm executed a counter-clockwise loop, ending on November 3, during which time numerous reconnaissance missions were flown into the system. By this time, the storm had also begun a southeastward track.[1]

Continuing to gradually intensify, Greta attained hurricane status on November 4 and later that day it attained Category 2 status on the modern day Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale.[2][4] After reaching this intensity, the hurricane turned northeastward and accelerated, although it did not intensify further. A reconnaissance mission around this time recorded a minimum pressure of 970 mbar (hPa; 28.64 inHg).[1]

Around the time it first reached peak intensity, Greta was an extraordinarily large hurricane, with the gale-diameter of the storm extending roughly 1,200 mi (1,930 km).[5][6][7] After attaining its peak intensity, the storm began to move over cooler waters, resulting in the circulation becoming elongated, however it did not weaken over the next couple days.[5] On the morning of November 6, Greta transitioned into an exceptionally large and intense extratropical cyclone.[2]

Preparations and impact

Although Greta did not directly track over land as a tropical storm or hurricane, the size of the system contributed to large waves, exceeding 20 ft (6.1 m) in height over a large expanse of the Atlantic. Impacts from the storm were felt as far away as the eastern United States.[1] The National Weather Bureau warned ships in the vicinity of the system to take precautions.[5] St. Croix was nearly isolated and stressed into an emergency due to Greta after the storm's swells destroyed docks and prevented ships carrying food from reaching the island. Several light vessels were destroyed by Greta's gale-force winds and only schooners with little carrying capacity were able to make it to the island.[8] Along the coast of Jacksonville, Florida alone, coastal structures sustained roughly $1.2 million (1956 USD; $9.6 million 2009 USD) in damages. In Puerto Rico, waves up to 20 ft (6.1 m) caused significant damage and resulted in the death of one person after he did not evacuate his home. Swells up to 25 ft (7.6 m) were recorded in the Virgin Islands. In Guadeloupe, 80% of the port installations were destroyed by rough seas. In all, damages from Greta amounted to roughly $3.6 million (1956 USD; $40.3 million 2024 USD).[1]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Gordon E. Dunn, Walter R. Davis and Paul L. Moore (December 1956). "Monthly Weather Review for 1956" (PDF). Weather Bureau Office. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c d National Hurricane Center (2009). "HURDAT: Easy-to-read version". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ Hurricane Research Division (2008). "Hurricane Research Division Milestones". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ The Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale was not created until 1971; storms prior to that year were called tropical storms or hurricanes

- ^ a b c Associated Press (November 6, 1956). "Greta Stays Far Out In Atlantic". Ocala Star-Banner. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ Mark DeMaria (2009). "Atlantic Extended Best Track Database: 1988-2008". Colorado State University. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ Mark DeMaria (2009). "Atlantic Extended Best Track Database: 1851-1987". Colorado State University. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ Staff Writer (November 15, 1956). "Shipping Plight". The Virgin Islands Daily News. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

External links