Environment of Svalbard

Svalbard is an Arctic, wilderness series of islands comprising the northernmost part of the Norwegian territories. It is mostly uninhabited, with only about 3,000 people, yet covers an area of 61,020 square kilometres (23,560 sq mi).

Geology

Devonian rocks on Svalbard, laid down in tropical conditions, reveal fossil lycopod forests which played an important role in absorbing carbon dioxide and so reducing global temperatures[1]

Fauna

In addition to humans, three primarily terrestrial mammalian species inhabit the archipelago: the Arctic fox, the Svalbard reindeer, and accidentally introduced southern vole—which is only found in Grumant.[2] Attempts to introduce the Arctic hare and the muskox have both failed.[3] There are fifteen to twenty types of marine mammals, including whales, dolphins, seals, walruses, and polar bears.[2]

Polar bears are the iconic symbol of Svalbard, and one of the main tourist attractions.[4] While the bears are protected, anyone outside of settlements is required to carry a rifle to kill polar bears in self defense, as a last resort should they attack.[5] Svalbard and Franz Joseph Land share a common population of 3,000 polar bears, with Kong Karls Land being the most important breeding ground. The Svalbard reindeer (R. tarandus platyrhynchus) is a distinct sub-species, and while previously almost extinct, hunting is permitted for both it and the Arctic fox.[2] There are a limited number of domesticated animals in Russian settlements.[6]

About thirty types of bird are found on Svalbard, most of which are migratory. The Barents Sea is among the areas in the world with most seabirds, with about 20 million individuals during late summer. The most common are little auk, northern fulmar, thick-billed murre and black-legged kittiwake. Sixteen species are on the IUCN Red List. Particularly Bjørnøya, Storfjorden, Nordvest-Spitsbergen and Hopen are important breeding ground for seabirds. The Arctic tern has the furthest migration, all the way to Antarctica.[2] Only two songbirds migrate to Svalbard to breed: the snow bunting and the wheatear. rock ptarmigan is the only bird to overwinter.[7] Remains of Predator X from the Jurassic period have been found; it is the largest dinosaur-era marine reptile ever found—a pliosaur estimated to be almost 15 m (49 ft) long.[8]

Most freshwater lakes on the islands are inhabited by Arctic char.[9]

Flora

Svalbard has permafrost and tundra, with both low, middle and high Arctic vegetation. There have been found 165 species of plants on the archipelago.[2] Only those areas which defrost in the summer have vegetations, which accounts for about 10% of the archipelago.[10] Vegetation is most abundant in Nordenskiöld Land, around Isfjorden and where effected by guano.[11] While there is little precipitation, giving the archipelago has a steppe climate, plants still have good access to water because the cold climate reduces evaporation.[2][12] The growing season is very short, and may only last a few weeks.[13]

Preserved areas

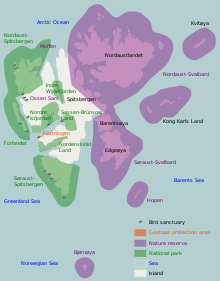

There are twenty-nine preserved natural areas, consisting of seven national parks, six nature reserves, fifteen bird sanctuaries and one geotope protected area.[2] In addition, human traces dating from before 1946 are automatically protected.[5] The protected areas make up 39,800 square kilometres (15,400 sq mi) or 65% of the land and 78,000 square kilometres (30,000 sq mi) or 86.5% of the territorial waters. The largest protected areas are Nordaust-Svalbard Nature Reserve and Søraust-Svalbard Nature Reserve, which cover most of the areas east of the main island of Spitsbergen, including the islands of Nordaustlandet, Edgeøya, Barentsøya, Kong Karls Land and Kvitøya. All seven national parks are located on Spitsbergen. Ten of the bird sanctuaries and Moffen Nature Reserve are located within a national park, while five of the bird sanctuaries are Ramsar sites.[2] Svalbard is on Norway's tentative list for nomination as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[14]

The supreme responsibility for conservation lies with the Norwegian Ministry of the Environment, which has delegated the management of the Governor of Svalbard and the Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management. The foundation for conservation was established in the Svalbard Treaty of 1920, and has further been specified in the Svalbard Environmental Act of 2001.[15] The first round of protection took force on 1 July 1973, when most of the current protected areas came into effect. This included the two large nature reserves and five of the national parks. Except Moffen Nature Reserve, which was established in 1983, the period from 2002 to 2005 saw several new areas protected.[2]

Climate

The climate of Svalbard is dominated by its high latitude, with the average summer temperature at 4 °C (39 °F) to 6 °C (43 °F) and January averages at −12 °C (10 °F) to −16 °C (3 °F).[16] The North Atlantic Current moderates Svalbard's temperatures, particularly during winter, giving it up to 20 °C (36 °F) higher winter temperature than similar latitudes in Russia and Canada. This keeps the surrounding waters open and navigable most of the year. The interior fjord areas and valleys, sheltered by the mountains, have less temperature differences than the coast, giving about 2 °C (4 °F) lower summer temperatures and 3 °C (5 °F) higher winter temperatures. On the south of Spitsbergen, the temperature is slightly higher than further north and west. During winter, the temperature difference between south and north is typically 5 °C (9 °F), while about 3 °C (5 °F) in summer. Bear Island has average temperatures even higher than the rest of the archipelago.[17]

Svalbard is the meeting place for cold polar air from the north and mild, wet sea air from the south, creating low pressure and changing weather and fast winds, particularly in winter; in January, a strong breeze is registered 17% of the time at Isfjord Radio, but only 1% of the time in July. In summer, particularly away from land, fog is common, with visibility under 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) registered 20% of the time in July and 1% of the time in January, at Hopen and Bjørnøya.[12] Precipitation is frequent, but falls in small quantities, typically less than 400 millimetres (16 in) in western Spitsbergen. More rain falls in the uninhabited east side, where there can be more than 1,000 millimetres (39 in).[12]

References

- ^ https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/news/view/163982-tropical-fossil-forests-unearthed-in-arctic-norway

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Protected Areas in Svalbard" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 33

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 174

- ^ a b Umbriet (2005): 132

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 165

- ^ Torkilsen (1984): 162

- ^ "Enormous Jurassic Sea Predator, Pliosaur, Discovered In Norway". Science Daily. 29 February 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ O'Malley, Kathleen G.; Vaux, Felix; Black, Andrew N. (2019). "Characterizing neutral and adaptive genomic differentiation in a changing climate: The most northerly freshwater fish as a model". Ecology and Evolution. 9 (4): 2004–2017. doi:10.1002/ece3.4891. PMC 6392408. PMID 30847088.

- ^ Torkilsen (1984): 144

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 29–30

- ^ a b c Torkilsen (1984): 101

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 32

- ^ "Svalbard". UNESCO. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Backer, Inge Lorang. "Svalbardloven". Norwegian National Authority for the Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ "Temperaturnormaler for Spitsbergen i perioden 1961 - 1990" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Meteorological Institute. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Torkilsen (1984): 98–99

Bibliography

- Torkildsen, Torbjørn; et al. (1984). Svalbard: vårt nordligste Norge (in Norwegian). Oslo: Forlaget Det Beste. ISBN 82-7010-167-2.

- Umbreit, Andreas (2005). Guide to Spitsbergen. Bucks: Bradt. ISBN 1-84162-092-0.