Radnage

| Radnage | |

|---|---|

St. Mary's parish Church | |

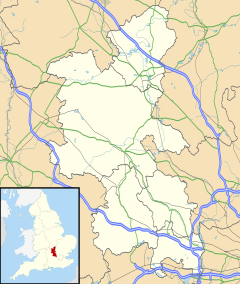

Location within Buckinghamshire | |

| Population | 658 [1] 673 (2011 Census)[2] |

| OS grid reference | SU7897 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | High Wycombe |

| Postcode district | HP14 |

| Dialling code | 01494 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Buckinghamshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Radnage |

Radnage is a village and civil parish in the Wycombe District of Buckinghamshire, England. It is in the Chiltern Hills about two miles north east of Stokenchurch and six miles WNW of High Wycombe.

The parish is set in folds of the Chiltern Hills to the south of Bledlow Ridge next to the border with Oxfordshire. Although not a large parish, the residential areas known as the City, Bennett End and Town End, are separate hamlets.

Radnage (also spelled Radeneach, Rodenache etc. in old documents) meant ‘red oak’ in Old English.

History

Settlement in the area dates back to Roman times as demonstrated by the excavation of a Romano-British glass ribbed bowl from the village, now in the British Museum.[3] Radnage is not mentioned in Domesday Book and it appears from a 13th-century document to have been royal demesne attached to the manor of Brill. Later, it was divided into two parts. The smaller part was granted by King Henry I to the newly established Fontevrault Abbey in France and attached to property at Leighton in Bedfordshire, which was also given to Fontevrault.

The larger part, known as Radnage Manor, was for a time retained by the crown and then in 1215 was granted by King John to the Knights Templar. When this order was suppressed in the early 14th century, their lands passed to the Knights Hospitaller. On the Dissolution of the Monasteries by King Henry VIII the manor was again acquired by the crown. King Charles I mortgaged it with other crown lands to the City of London in order to raise money. Later, King Charles II was said to have given it to one of his mistresses. But by the 19th century both parts of the manor again belonged to the crown and so remained until the abolition of manorial rights in 1925.[4]

Church of St Mary the Virgin

This church was built around the year 1200 in much the same form as it appears today, though larger windows were inserted in the 14th century and the nave appears to have been lengthened and heightened in the 15th century, when the present roof was built. There is a central tower, which is unusual in being narrower than either the chancel or the nave.

There are three original lancet windows of the early 13th century in the east wall of the chancel. The other windows in the church are 14th century. The south doorway is original of the early 13th century. A similar north doorway has been blocked up. The south porch and outer door are original of the 13th century, but with a 15th-century roof and 15th-century windows in the side walls.

The fine 15th-century nave roof has embattled tie-beams supported by arched brackets with tracery in the spandrels and also in the triangular spaces above the beams. The lower-pitched chancel roof is probably 16th century.

Inside the church there is an archway through the tower with 13th-century arches in pointed style at either end. The chancel has a 13th-century piscina (damaged) in the south wall. The nave has traces of early wall painting and also post-Reformation texts (16th-to-18th-century). The font is probably 17th-century.[5]

References

Books mentioned in the notes

- VHCB = Victoria History of the County of Buckingham, ed: William Page, Volume 3 (1925)

- Pevsner, Nikolaus & Elizabeth Williamson: Buckinghamshire (The Buildings of England - Penguin Books. 2nd edition. 1994)

- RCHMB = Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England): An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Buckinghamshire, Volume 1 South (1912)

Notes

- ^ Neighbourhood Statistics 2001 Census

- ^ "Civil Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ^ British Museum Collection

- ^ VHCB vol.3 p.90

- ^ For the history and architecture of the church, see VHCB Vol.3 pp.91-2, RCHMB pp.274-5 and Pevsner & Wiiliamson pp.612-3