Wolf interval

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2008) |

In music theory, the wolf fifth (sometimes also called Procrustean fifth, or imperfect fifth)[1][2] is a particularly dissonant musical interval spanning seven semitones. Strictly, the term refers to an interval produced by a specific tuning system, widely used in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries: the quarter-comma meantone temperament.[3] More broadly, it is also used to refer to similar intervals produced by other tuning systems, including most meantone temperaments.

When the twelve notes within the octave of a chromatic scale are tuned using the quarter-comma mean-tone systems of temperament, one of the twelve intervals spanning seven semitones (classified as a diminished sixth) turns out to be much wider than the others (classified as perfect fifths). In mean-tone systems, this interval is usually from C♯ to A♭ or from G♯ to E♭ but can be moved in either direction to favor certain groups of keys.[4] The eleven perfect fifths sound almost perfectly consonant. Conversely, the diminished sixth is severely dissonant and seems to howl like a wolf, because of a phenomenon called beating. Since the diminished sixth is meant to be enharmonically equivalent to a perfect fifth, this anomalous interval has come to be called the wolf fifth.

Besides the above-mentioned quarter comma meantone, other tuning systems may produce severely dissonant diminished sixths. Conversely, in 12-tone equal temperament, which is currently the most commonly used tuning system, the diminished sixth is not a wolf fifth, as it has exactly the same size as a perfect fifth.

By extension, any interval which is perceived as severely dissonant and may be regarded as howling like a wolf may be called a wolf interval. For instance, in quarter comma meantone, the augmented second, augmented third, augmented fifth, diminished fourth and diminished seventh may be considered wolf intervals, as their size significantly deviates from the size of the corresponding justly tuned interval (see Size of quarter-comma meantone intervals).

Temperament and the wolf

In 12-tone scales, the average value of the twelve fifths must equal the 700 cents of equal temperament. If eleven of them have a value of 700 − ε cents, as in quarter-comma meantone and most other meantone temperament tuning systems, the other fifth (more properly called a diminished sixth) will equal 700 + 11ε cents. The value of ε changes depending on the tuning system. In other tuning systems (such as Pythagorean tuning and twelfth-comma meantone), eleven fifths may have a size of 700 + ε cents, thus the diminished sixth is 700 − 11ε cents. If 11ε is very large, as in the quarter-comma meantone tuning system, the diminished sixth is regarded as a wolf fifth.

In terms of frequency ratios, the product of the fifths must be 128, and if f is the size of a fifth, 128:f11, or f11:128, will be the size of the wolf.

We likewise find varied tunings for the thirds. Major thirds must average 400 cents, and to each pair of thirds of size 400 ∓ 4ε cents we have a third (or diminished fourth) of 400 ± 8ε cents, leading to eight thirds 4ε cents narrower or wider, and four diminished fourths 8ε cents wider or narrower than average. Three of these diminished fourths form major triads with perfect fifths, but one of them forms a major triad with the diminished sixth. If the diminished sixth is a wolf interval, this triad is called the wolf major triad.

Similarly, we obtain nine minor thirds of 300 ± 3ε cents and three minor thirds (or augmented seconds) of 300 ∓ 9ε cents.

Quarter comma meantone

In quarter-comma meantone, the fifth is of size 4√5, about 3.42157 cents (or exactly one twelfth of a diesis) flatter than 700 cents, and so the wolf is about 737.637 cents, or 35.682 cents sharper than a perfect fifth of size exactly 3:2, and this is the original howling wolf fifth.

The flat minor thirds are only about 2.335 cents sharper than a subminor third of size 7:6, and the sharp major thirds, of size exactly 32:25, are about 7.712 cents flatter than the supermajor third of 9:7. Meantone tunings with slightly flatter fifths produce even closer approximations to the subminor and supermajor thirds and corresponding triads. These thirds therefore hardly deserve the appellation of wolf, and in fact historically have not been given that name.

Pythagorean tuning

In Pythagorean tuning, there are eleven justly tuned fifths sharper than 700 cents by about 1.955 cents (or exactly one twelfth of a Pythagorean comma), and hence one fifth will be flatter by twelve times that, which is 23.460 cents (one Pythagorean comma) flatter than a just fifth. A fifth this flat can also be regarded as howling like a wolf. There are also now eight sharp and four flat major thirds.

Five-limit tuning

Five-limit tuning was designed to maximize the number of pure intervals, but even in this system several intervals are markedly impure. 5-limit tuning yields a much larger number of wolf intervals with respect to Pythagorean tuning, which can be considered a 3-limit just intonation tuning. Namely, while Pythagorean tuning determines only 2 wolf intervals (a fifth and a fourth), the 5-limit symmetric scales produce 12 of them, and the asymmetric scale 14. It is also important to note that the two fifths, three minor thirds, and three major sixths marked in orange in the tables (ratio 40/27, 32/27, and 27/16 (or G−, E♭−, and A+), even though they do not completely meet the conditions to be wolf intervals, deviate from the corresponding pure ratio by an amount (1 syntonic comma, i.e., 81/80, or about 21.5 cents) large enough to be clearly perceived as dissonant.

Five-limit tuning determines one diminished sixth of size 1024:675 (about 722 cents, i.e. 20 cents sharper than the 3:2 Pythagorean perfect fifth). Whether this interval should be considered dissonant enough to be called a wolf fifth is a controversial matter.

Five-limit tuning also creates two impure perfect fifths of size 40:27 (about 680 cents; less pure than the 3:2 Pythagorean perfect fifth). These are not diminished sixths, but relative to the Pythagorean perfect fifth they are less consonant (about 20 cents flatter) and hence, they might be considered to be wolf fifths. The corresponding inversion is an impure perfect fourth of size 27:20 (about 520 cents). For instance, in the C major diatonic scale, an impure perfect fifth arises between D and A, and its inversion arises between A and D.

Since the term perfect means, in this context, perfectly consonant,[5] the impure perfect fourth and perfect fifth are sometimes simply called imperfect fourth and fifth.[2] However, the widely adopted standard naming convention for musical intervals classifies them as perfect intervals, together with the octave and unison. This is also true for any perfect fourth or perfect fifth which slightly deviates from the perfectly consonant 4:3 or 3:2 ratios (for instance, those tuned using 12-tone equal or quarter-comma meantone temperament). Conversely, the expressions imperfect fourth and imperfect fifth do not conflict with the standard naming convention when they refer to a dissonant augmented third or diminished sixth (e.g. the wolf fourth and fifth in Pythagorean tuning).

"Taming the wolf"

Wolf intervals are a consequence of mapping a two-dimensional temperament to a one-dimensional keyboard.[6] The only solution is to make the number of dimensions match. That is, either:

- Keep the (one-dimensional) piano keyboard, and shift to a one-dimensional temperament (e.g., equal temperament), or

- Keep the two-dimensional temperament, and shift to a two-dimensional keyboard.

Keep the piano keyboard

When the perfect fifth is tempered to be exactly 700 cents wide (that is, tempered by approximately 1⁄11 of a syntonic comma, or exactly 1⁄12 of a Pythagorean comma) then the tuning is identical to the familiar 12-tone equal temperament.

Because of the compromises (and wolf intervals) forced on meantone tunings by the one-dimensional piano-style keyboard, well temperaments and eventually equal temperament became more popular.

A fifth of the size Mozart favored, at or near the 55-equal fifth of 698.182 cents, will have a wolf of 720 cents, 18.045 cents sharper than a justly tuned fifth. This howls far less acutely, but still very noticeably.

The wolf can be tamed by adopting equal temperament or a well temperament. The very intrepid may simply want to treat it as a xenharmonic music interval; depending on the size of the meantone fifth it can be made to be exactly 20:13 or 17:11, or less commonly to 32:21 or 49:32.

With a more extreme meantone temperament, like 19 equal temperament, the wolf is large enough that it is closer in size to a sixth than a fifth, and sounds like a different interval altogether rather than a mistuned fifth.

Keep the two-dimensional tuning system

To use a two-dimensional temperament without wolf intervals, one needs a two-dimensional keyboard that is "isomorphic" with that temperament. A keyboard and temperament are isomorphic if they are generated by the same intervals. For example, the Wicki keyboard shown in Figure 1 is generated by the same musical intervals as the syntonic temperament — that is, by the octave and tempered perfect fifth — so they are isomorphic.

On an isomorphic keyboard, any given musical interval has the same shape wherever it appears — in any octave, key, and tuning — except at the edges. For example, on Wicki's keyboard, from any given note, the note that is a tempered perfect fifth higher is always up-and-rightwardly adjacent to the given note. There are no wolf intervals within the note-span of this keyboard. The only problem is at the edge, on the note E♯. The note that is a tempered perfect fifth higher than E♯ is B♯, which is not included on the keyboard shown (although it could be included in a larger keyboard, placed just to the right of A♯, hence maintaining the keyboard's consistent note-pattern). Because there is no B♯ button, when playing an E♯ power chord, one must choose some other note that is close in pitch to B♯, such as C, to play instead of the missing B♯. That is, the interval from E♯ to C would be a "wolf interval" on this keyboard.

However, such edge conditions produce wolf intervals only if the isomorphic keyboard has fewer buttons per octave than the tuning has enharmonically distinct notes.[6] For example, the isomorphic keyboard in Figure 2 has 19 buttons per octave, so the above-cited edge condition, from E♯ to C, is not a wolf interval in 12-TET, 17-TET, or 19-TET; however, it is a wolf interval in 26-TET, 31-TET, and 53-TET. In these latter tunings, using electronic transposition could keep the current key's notes centered on the isomorphic keyboard, in which case these wolf intervals would very rarely be encountered in tonal music, despite modulation to exotic keys.[8]

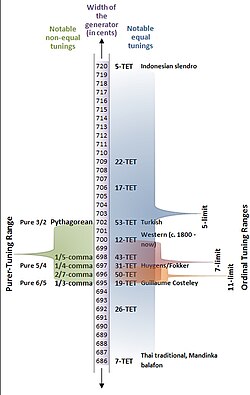

A keyboard that is isomorphic with the syntonic temperament, such as Wicki's keyboard above, retains its isomorphism in any tuning within the tuning continuum of the syntonic temperament, even when changing tuning dynamically among such tunings.[8] Figure 2 shows the valid tuning range of the syntonic temperament.

Listen to it

Listen to the two fifths here:

References

- ^ A.L. Leigh Silver (1971), p.354

- ^ a b Paul, Oscar (1885). A manual of harmony for use in music-schools and seminaries and for self-instruction, p.165. Theodore Baker, trans. G. Schirmer.

- ^ The wolf fifth

- ^ Duffin, Ross W. (2007). How Equal Temperament Ruined Harmony (and Why You Should Care). New York: W. W. Norton. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-393-06227-4.

- ^ Definition of Perfect consonance in Godfrey Weber's General music teacher, by Godfrey Weber, 1841.

- ^ a b c Milne, Andrew; Sethares, William; Plamondon, James (December 2007). "Invariant Fingerings Across a Tuning Continuum". Computer Music Journal. 31 (4): 15–32. doi:10.1162/comj.2007.31.4.15. Retrieved 2013-07-11.

- ^ Gaskins, Robert (September 2003). "The Wicki System—an 1896 Precursor of the Hayden System". Concertina Library: Digital Reference Collection for Concertinas. Retrieved 2013-07-11.

- ^ a b Plamondon, Jim; Milne, A.; Sethares, W.A. (2009). "Dynamic Tonality: Extending the Framework of Tonality into the 21st Century" (PDF). Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the South Central Chapter of the College Music Society.