John Latham (judge)

Sir John Latham | |

|---|---|

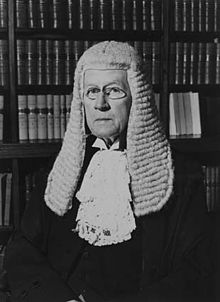

Latham in 1931 | |

| 5th Chief Justice of Australia | |

| In office 11 October 1935 – 7 April 1952 | |

| Nominated by | Joseph Lyons |

| Appointed by | Sir Isaac Isaacs |

| Preceded by | Sir Frank Gavan Duffy |

| Succeeded by | Sir Owen Dixon |

| Leader of the Opposition | |

| In office 22 October 1929 – 7 May 1931 | |

| Prime Minister | James Scullin |

| Preceded by | James Scullin |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Lyons |

| Leader of the Nationalist Party | |

| In office 22 October 1929 – 7 May 1931 | |

| Preceded by | Stanley Bruce |

| Succeeded by | Position Abolished |

| Member of the Australian Parliament for Kooyong | |

| In office 16 December 1922 – 7 August 1934 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Best |

| Succeeded by | Robert Menzies |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 26 August 1877 Ascot Vale, Victoria, Australia |

| Died | 25 July 1964 (aged 86) Richmond, Victoria, Australia |

| Political party | Liberal Union (1921–1925) Nationalist (1925–1931) United Australia (1931–1934) |

| Spouse |

Ella Tobin (m. 1907) |

| Education | Scotch College |

| Alma mater | University of Melbourne |

Sir John Greig Latham GCMG QC (26 August 1877 – 25 July 1964) was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge who served as the fifth Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1935 to 1952. He had earlier served as Attorney-General of Australia under Stanley Bruce and Joseph Lyons, and was Leader of the Opposition from 1929 to 1931 as the final leader of the Nationalist Party.

Latham was born in Melbourne. He studied arts and law at the University of Melbourne, and was called to the bar in 1904. He soon became one of Victoria's best known barristers. In 1917, Latham joined the Royal Australian Navy as the head of its intelligence division. He served on the Australian delegation to the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, where he came into conflict with Prime Minister Billy Hughes. At the 1922 federal election, Latham was elected to parliament as an independent on an anti-Hughes platform. He got on better with Hughes' successor Stanley Bruce, and formally joined the Nationalist Party in 1925, subsequently winning promotion to cabinet as Attorney-General. He was also Minister for Industry from 1928, and was one of the architects of the unpopular industrial relations policy that contributed to the government's defeat at the 1929 election. Bruce lost his seat, and Latham was reluctantly persuaded to become Leader of the Opposition.

In 1931, Latham led the Nationalists into the new United Australia Party, joining with Joseph Lyons and other disaffected Labor MPs. Despite the Nationalists forming a larger proportion of the new party, he relinquished the leadership to Lyons, a better campaigner, thus becoming the first opposition leader to fail to contest a general election. In the Lyons Government, Latham was the de facto deputy prime minister, serving both as Attorney-General and Minister for External Affairs. He retired from politics in 1934, and the following year was appointed to the High Court as Chief Justice. From 1940 to 1941, Latham took a leave of absence from the court to become the inaugural Australian Ambassador to Japan. He left office in 1952 after almost 17 years as Chief Justice; only Garfield Barwick has served for longer.

Early life and education

Latham was born in Ascot Vale, a suburb of Melbourne, Australia. His father was a prominent citizen, whose achievements as secretary for the Society for the Protection of Animals were deeply respected. John Latham won a scholarship and became a successful student at Scotch College and the University of Melbourne, studying logic, philosophy and law. At one point, he was the recipient of the Supreme Court Judges' Prize. In November 1902, Latham became the first secretary of the Boobook Society (named for the southern boobook owl), a group of Melbourne academics and professionals which still meets.[citation needed]

Career

Naval career

During World War I, he was an intelligence officer in the Royal Australian Navy, holding the rank of lieutenant commander. He was the head of Naval Intelligence from 1917, and was part of the Australian delegation to the Imperial Conference and then the Versailles Peace Conference, for which he was appointed Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in the 1920 New Year Honours.[1] He grew to dislike Prime Minister Billy Hughes.

Legal career

Latham had a distinguished legal career. He was admitted to the Victorian Bar in 1904, and was made a King's Counsel in 1922. In 1920, Latham appeared before the High Court representing the State of Victoria in the famous Engineers' case, alongside such people as Dr H.V. Evatt and Robert Menzies.

Political career

In 1922, Latham was elected to the Australian House of Representatives for Kooyong in eastern Melbourne. Although his philosophy was close to Hughes' Nationalist Party, Latham's experience of Hughes in Europe ensured that he would not serve under him in a Parliament. Instead, he initially aligned himself with the Liberal Union, a group of conservatives opposed to Hughes; his campaign slogan was 'Get Rid of Hughes'. On Hughes' removal in 1923, he subsequently joined the Nationalist Party (though he officially remained a Liberal until 1925). From 1925 to 1929, he served as the Commonwealth Attorney-General in the Bruce–Page government. He wrote several books, including Australia and the British Empire in which he argued for Australia's place in the British Empire.

After Bruce lost his Parliamentary seat in 1929, Latham was elected as leader of the Nationalist Party, and hence Leader of the Opposition. He opposed the ratification of the Statute of Westminster (1931) and worked very hard to prevent it.[2]

Two years later, Joseph Lyons led defectors from the Labor Party across the floor and merged them with the Nationalists to form the United Australia Party. Although the new party was dominated by former Nationalists, Latham agreed to become Deputy Leader of the Opposition under Lyons. It was believed having a former Labor man at the helm would present an image of national unity in the face of the economic crisis. Additionally, the affable Lyons was seen as much more electorally appealing than the aloof Latham, especially given that the UAP's primary goal was to win over natural Labor constituencies to what was still, at bottom, an upper- and middle-class conservative party. Future ALP leader Arthur Calwell wrote in his autobiography, Be Just and Fear Not, that by standing aside in favour of Lyons, Latham knew he was giving up a chance to become Prime Minister.

The UAP won a huge victory in the 1931 election, and Latham was appointed Attorney-General once again. He also served as Minister for External Affairs and (unofficially) the Deputy Prime Minister. Latham held these positions until 1934, when he retired from the Commonwealth Parliament. He was succeeded as member for Kooyong, Attorney-General and Minister of Industry by Menzies, who would go on to become Australia's longest-serving Prime Minister.

Judicial career

Latham was appointed Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia on 11 October 1935. From 1940 to 1941, he took leave from the Court and travelled to Tokyo to serve as Australia's first Minister to Japan. He retired from the High Court in April 1952, after a then-record 16 years in office.

As Chief Justice, Latham corresponded with political figures to an extent later writers have viewed as inappropriate. Latham offered advice on political matters – frequently unsolicited – to several prime ministers and other senior government figures. During World War II, he made a number of suggestions about defence and foreign policy,[3] and provided John Curtin with a list of constitutional amendments he believed should be made to increase the federal government's power.[4] Towards the end of his tenure, Latham's correspondence increasingly revealed his personal views on major political issues that had previously come before the court; namely, opposition to the Chifley Government's health policies and support of the Menzies Government's attempt to ban the Communist Party. He advised Earle Page on how the government could amend the constitution to legally ban the Communist Party,[5] and corresponded with his friend Richard Casey on ways to improve the Liberal Party's platform.[6]

According to Fiona Wheeler, there was no direct evidence that Latham's political views interfered with his judicial reasoning, but "the mere appearance of partiality is enough for concern" and could have been difficult to refute if uncovered. She particularly singles out his correspondence with Casey as "an extraordinary display of political partisanship by a serving judge.[7] Although Latham emphasised the need for secrecy to the recipients of his letters, he retained copies of most of them in his personal papers, apparently unconcerned that they could be discovered and analysed after his death. He rationalised his actions as those of a private individual, separate from his official position, and maintained a "Janus-like divide between his public and private persona". In other fora he took pains to demonstrate his independence, rejecting speaking engagements if he believed they could be construed as political statements.[8] Nonetheless, "many instances of Latham's advising [...] would today be regarded as clear affronts to basic standards of judicial independence and propriety".[9]

Latham was one of only eight justices of the High Court to have served in the Parliament of Australia prior to his appointment to the Court; the others were Edmund Barton, Richard O'Connor, Isaac Isaacs, H. B. Higgins, Edward McTiernan, Garfield Barwick, and Lionel Murphy.

Personal life

He was a prominent rationalist and atheist,[10] after abandoning his parents' Methodism at university. It was at this time that he ended his engagement to Elizabeth (Bessie) Moore, the daughter of Methodist Minister Henry Moore. Bessie later married Edwin P. Carter on the 18th May 1911 at the Northcote Methodist Church, High Street, Northcote.

Latham married Eleanor Mary Tobin, known as Ella.[11] They had three children, two of whom predeceased him. His wife, Ella, also predeceased him. Latham died in 1964 in the Melbourne suburb of Richmond.

He was also a prominent campaigner for Australian literature, being part of the editorial board of The Trident, a small liberal journal, which was edited by Walter Murdoch. The board also included poet Bernard O'Dowd.

Legacy

The Canberra suburb of Latham was named after him in 1971. There is also a lecture theatre named after him at The University of Melbourne.

Footnotes

- ^ "No. 31712". The London Gazette (Supplement). 30 December 1919. p. 4.

- ^ Lewis, David (3 July 1998). "John Latham and the Statute of Westminster". Archived from the original on 11 April 2011.

- ^ Wheeler (2011).

- ^ Wheeler (2011), p. 664.

- ^ Wheeler (2011), pp. 669–671.

- ^ Wheeler (2011), pp. 667–8.

- ^ Wheeler (2011), p. 666.

- ^ Wheeler (2011), p. 653.

- ^ Wheeler (2011), p. 672.

- ^ Morgan (2005), p. 144.

- ^ "Latham, Eleanor Mary". The Encyclopedia of Women and Leadership in Twentieth-Century Australia. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

References

- Cowen, Zelman (1965). Sir John Latham and Other Papers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195500563.

- Macintyre, Stuart (1986). "Latham, Sir John Greig (1877–1964)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 10. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. pp. 2–6. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943.

- Morgan, D (2005). The Australian Miscellany. Bantam. ISBN 1 86325 537 0.

- Wheeler, Fiona. "Sir John Latham's extra-judicial advising" (PDF). (2011) 35(2) Melbourne University Law Review 651.

External links

- 1877 births

- 1964 deaths

- Lawyers from Melbourne

- Ambassadors of Australia to Japan

- Attorneys-General for Australia

- Australian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

- Australian politicians awarded knighthoods

- Australian Leaders of the Opposition

- Australian ministers for Foreign Affairs

- Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- Melbourne Law School alumni

- Nationalist Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia

- United Australia Party members of the Parliament of Australia

- Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Kooyong

- Members of the Australian House of Representatives

- Members of the Cabinet of Australia

- Royal Australian Navy officers

- Australian military personnel of World War I

- Chief Justices of Australia

- Justices of the High Court of Australia

- People educated at Scotch College, Melbourne

- Australian lacrosse players

- Australian Queen's Counsel

- Australian atheists

- Judges from Melbourne

- Liberal Party (1922) members of the Parliament of Australia

- Leaders of the Nationalist Party of Australia

- 20th-century Australian politicians