So Little Time (film)

| So Little Time | |

|---|---|

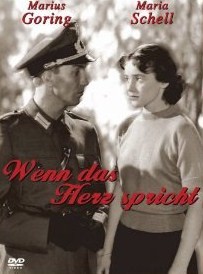

German DVD cover | |

| Directed by | Compton Bennett |

| Written by | Noelle Henry (novel) John Cresswell |

| Produced by | Aubrey Baring Maxwell Setton |

| Starring | Marius Goring Maria Schell Lucie Mannheim |

| Cinematography | Oswald Morris |

| Edited by | Vladimir Sagovsky |

| Music by | Louis Levy |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Associated British Picture Corporation |

Release date | March 1952 |

Running time | 88 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Box office | £91,096 (UK)[1] |

So Little Time is a 1952 British World War II romance drama directed by Compton Bennett and starring Marius Goring, Maria Schell and Lucie Mannheim.

The film is based on the novel Je ne suis pas une héroïne by French author Noëlle Henry. So Little Time is unusual for its time in portraying its German characters in a mainly sympathetic manner, while the Belgian Resistance characters are depicted in an aggressive, almost gangster-type light. So soon after the war, this was not a narrative viewpoint British audiences and critics expected in a British film and there was considerable protest about the film's content.[2] Marius Goring considered it as one of his favourite films and was a rare romantic leading role for him, though one of several films in which he played a German officer.

The film was made at Elstree Studios with sets designed by Edward Carrick. Location shooting was done over twenty days in Belgium and the Château de Sterrebeek at Zoutleeuw (Léau) near Brussells was used as the Château de Malvines. Filmed during 1951, it was released in March 1952.

Plot

In occupied Belgium during World War II, the chateau where Nicole de Malvines (Maria Schell) lives with her mother (Gabrielle Dorziat) is partially requisitioned for use by German forces. Among those billeted there is Colonel Günther von Hohensee (Marius Goring), a ruthlessly efficient Prussian officer. Having lost several male members of her family in the war, the proud and outspoken Nicole holds the Germans in contempt and has no hesitation in making her feelings clear to him.

Nicole and von Hohensee discover a mutual love of music, particularly the piano, and Günther starts to coach her. This gradually brings them together and, despite their differences, and the inherent danger of the situation to both, they fall in love. They travel to Brussels to attend the opera, acutely aware of the need to be discreet and the risks involved in being seen socialising with one another. Matters become more complicated when members of the Belgian Resistance, led by her cousin Phillipe de Malvines (John Bailey), target Nicole to steal documentation from von Hohensee to pass over to them, making clear that non-cooperation is not an option.

The couple realise that, in one way or another, the relationship is doomed. A sympathetic observer who has noticed their love, his former lover, the opera singer Lotte Schönberg (Lucie Mannheim), urges Günther to tell Nicole that he loves her and to make the most of it while they can, because there is "so little time". Günther readily admits that he loves Nicole and believes that she loves him too but refuses to tell her as he feels that there is too much to prevent any future for them. He tells Lotte that he has applied for a transfer back to frontline duties.

Matters come to a head after Günther tries to push Nicole away by humiliating one of her friends, Gerard. They argue furiously and are estranged for a few days but, when Nicole learns he is to leave soon, she confronts him one night and begs him not to go. He can no longer resist her and they declare their love for each other. Inevitably, they are betrayed and have to face being parted forever. Günther discovers that Nicole has stolen documents from his desk and confronts her after she returns from delivering them to her cousin, Phillipe. Nicole is shot by mistake by her cousin while he is trying to kill von Hohensee and dies in Günther's arms. Unable to reconcile himself to the situation,[3] and knowing that he will be arrested by the Gestapo, von Hohensee shoots himself.

Cast

- Marius Goring as Colonel Günther von Hohensee

- Maria Schell as Nicole de Malvines

- Lucie Mannheim as Lotte Schönberg

- Gabrielle Dorziat as Mme. de Malvines

- Barbara Mullen as Anna

- John Bailey as Phillipe de Malvines

- David Hurst as Blumel

- Oscar Quitak as Gerard

- Andrée Melly as Paulette

- Stanley van Beers as Professor Perronet

Production

The film was going to be directed by Max Ophuls and was set in France. French authorities complained so the action was relocated to Belgium.[4]

Music

The film used several piano pieces played by classical pianist Shura Cherkassky. These include the Piano Sonata in B minor by Franz Liszt, which is used as the main theme music and the piece that von Hohensee first starts coaching Nicole in, and Piano Études by Frédéric Chopin. The aria Voi che sapete che cosa è amor or Sagt holde Frauen die ihr sie kennt from the opera The Marriage of Figaro by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart also features prominently in the film, being sung in German, both by von Hohensee as he accompanies himself on piano, and in the performance which von Hohensee takes Nicole to see in Brussells.

Marius Goring is seen playing the piano throughout the film - it is actually him playing as he was a skilled amateur pianist.

Reception

Unfortunately, the subject matter of the film was not to the taste of the British public when it was released in April 1952, and there was some controversy about its subject matter, particularly portraying a German officer so sympathetically. Marius Goring was philosophical about it: “A touching little film,” said Goring later, “my favourite apart from the Powell films. It was too soon after the war and people thought every German was a horror...its timing was wrong.”

Reviews by critics were generally positive: The Times described it as “a modest, a sensitive, a touching little film”. While describing the plot as “stuff and nonsense” it however goes on to say: “But Miss Schell - and Mr Goring greatly helps with his firm drawing of the colonel - puts a spell upon the stuff and the nonsense, making it dissolve and setting in its place a glowing portrait of a very young and heart-breakingly defenceless girl utterly in love.”

C.A. Lejeune in The Observer commented that it “...gives a sentimental treatment where sentiment may seem out of place, but once we have accepted that, there is much left in the film to appreciate. Pictorially, it is almost always a delight; in particular, I liked the recurring shots of the neat white chateau, reflected in its lake so that the whole thing looked like a double doll's-house. Mr Goring plays a difficult part with great integrity and just the right mixture of tenderness and chill. Miss Schell is adorable, with her heart-shaped face and wings of dark hair; her quaint way of sitting, looking down and sideways with the head a little tilted, her trick of speaking softly on the middle of an outgoing breath. I thought her very touching, and altogether sweet.”

The review by Marjory Adam in The Boston Globe said: “ 'So Little Time' is sentimentally appealing but it has emotional heights as well. Nicole's sacrifice to save her lover whom she has betrayed to her countrymen rises to almost unbearable intensity as the terrified girl runs sobbing to stop his car. As for Goring, he is excellent as the haughty Prussian whose heart is torn between duty and devotion to the Belgian girl. Miss Schell and Goring display sensitivity and skill in delineating the love which is so tender in a rough and wicked world of war and death. Here is a film which was made for lovers.”

Home media

So Little Time was released commercially on DVD in November 2015. A dubbed German-language version under the title Wenn das Herz spricht (When the Heart Speaks) was released to the German market in 2005.

References

- ^ Vincent Porter, 'The Robert Clark Account', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Vol 20 No 4, 2000 p498

- ^ Time Out Film Guide, Penguin Books London, 1989, p.551 ISBN 0-14-012700-3

- ^ Last scenes

- ^ Harper, Sue; Porter, Vincent (2003). British Cinema of the 1950s: The Decline of Deference. Oxford University Press. pp. 178–180.