J. C. Bloem

J. C. Bloem | |

|---|---|

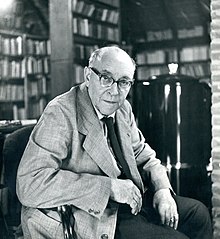

Bloem in his study in 1933 | |

| Born | 10 May 1887 |

| Died | 10 August 1966 |

| Spouse(s) | Clara Eggink |

Jakobus Cornelis (Jacques) Bloem (10 May 1887, Oudshoorn – 10 August 1966, Kalenberg) was a Dutch poet and essayist. Between 1921 and 1958 he published fourteen volumes of poetry.[1] In 1949 he won the Constantijn Huygensprijs, one of the country's highest literary awards, and in 1952 the P. C. Hooft Award for his literary oeuvre. In 1965, in rapidly declining health, he was awarded the highest Dutch-language literary award, the Prijs der Nederlandse Letteren. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature.[2]

Dubbed the poet of unfulfilled desire, he is hailed as one of the 100 greatest Netherlanders of the twentieth century.[3]

The Dutch poetry award J.C. Bloem-poëzieprijs is named after him.

Life

In his early years, Bloem was a great admirer of the symbolist poetry of Charles Baudelaire;[4] it is, however, for a relatively simple, almost naive poem that he is best remembered in the Netherlands, "Domweg Gelukkig in de Dapperstraat", "simply (or foolishly) happy in the Dapperstraat", a market street in East Amsterdam.[5] The poem also lent its title to a popular anthology of Dutch poetry.[6] His legacy, beside his poetry, remains a bit controversial: he was suspected of antisemitism and of sympathizing, at least initially, with the German Nazi government, and in a recent biography the possibility of his having been homosexual was proposed.[7] Still, his importance to the country was reaffirmed at the fortieth anniversary of his death, a celebration of his life and work in Paasloo, where he and his wife Clara Eggink were buried.[8]

Select bibliography

- Het verlangen. 1921.

- Media vita. 1931.

- Nederlaag. 1937.

- Sintels. 1945.

- Quiet though sad: gedichten ’s-Gravenhage, A.A.M. Stols, 1946.

- Verzamelde gedichten. ’s-Gravenhage, A. A. M. Stols, 1947.

- Verzamelde Beschouwingen. ’s-Gravenhage, A.A.M. Stol, 1950.

- Afscheid. ’s-Gravenhage: L. J. C. Boucher, 1957.

- Poëtica. Amsterdam: Athenaeum/Polak & Van Gennep, 1969.

- Ongewild archief. ’s-Gravenhage: BZZTôH, 1977. ISBN 90-6291-009-2.

References

- ^ "J.C. Bloem 1887-1966". Digitale Bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse Letteren. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Nomination Database". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2017-04-19.

- ^ Truijens, Aleid (2002-10-10). "Dichter van het eeuwig onvervuld verlangen" (in Dutch). De Volkskrant. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Buurlage, Jos (2004). "Bloem neemt afstand van Baudelaire". Nieuw Letterkundig Magazijn. 22: 38–41. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Truijens, Aleid (2008-09-26). "Een kind begrijpt het" (in Dutch). De Volkskrant. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ de Vrind, Bram (2008-03-21). "Dichtregels maken uit beelden en mythes" (in Dutch). Brabants Dagblad. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Abrahams, Frits (2006-03-22). "Gekneusde liefde" (in Dutch). NRC Handelsblad. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Groenewoud, Marion (2006-04-10). "Herdenking Bloem: stand-up comedy" (in Dutch). De Stentor. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)