Dinosaur coloration

Dinosaur color is one of the unknowns in the field of paleontology as skin pigmentation is nearly always lost during the fossilization process. However, recent studies of feathered dinosaurs have shown that we might be able to infer the color of some species through the use of melanosomes, the color-determining pigments within the feathers.

Feathered dinosaurs

Anchiornis

In 2010, paleontologists studied a well-preserved skeleton of Anchiornis, an averaptoran from the Tiaojishan Formation in China, and found melanosomes within its fossilized feathers. As different shaped melanosomes determine different colors, analysis of the melanosomes allowed the paleontologists to infer that Anchiornis had black, white and grey feathers all over its body and a crest of dark red or ochre feathers on its head.[1]

Another specimen was reported to possess melanosomes which induced grey and black coloration, but none that suggested red or brown coloration.[2]

Sinosauropteryx

In 2010 Dr. Mike Benton from the University of Bristol[3] analyzed the remains of Sinosauropteryx, Confuciusornis, Caudipteryx,[4] and Sinornithosaurus from the Yixian and also discovered melanosomes. It was determined that Sinosauropteryx had orange feathers and that its tail was striped. Given the feathers were brightly colored and ill-suited for flight it is hypothesized that this species used its feathers for display. A 2017 study also reported that the body coloration of Sinosauropteryx extended to the face, creating a raccoon-like "mask" around the eyes.[5]

Archaeopteryx

In 2011 graduate student Ryan Carney and colleagues produced the first color study on an Archaeopteryx specimen; fossilized melanosomes suggested a primarily black coloration in the feathers of the specimen. The feather studied was likely a covert, which would have partly covered the primary feathers on the wings. Carney pointed out that this is consistent with the flight feathers of modern birds, in which black melanosomes have structural properties that strengthen feathers for flight.[6]

In 2013, a study published in the Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry reported new analyses revealing that Archaeopteryx may have had light and dark colored plumage, with only the tips of its flight feathers being primarily black instead of the entire feather. Whether or not this coloration was primarily for display or flight is as yet unknown.[7]

Microraptor

According to a 2012 study by Quanguo Li and team of specimen BMNHC PH881 the coloration of the feathers of a typical Microraptor was iridescent black. The melanosomes were narrow and arranged in stacked layers, reminiscent of the blackbird. It is believed that Microraptor were nocturnal due to size of the scleral ring in its eye. However, now that its feathers have been determined to be iridescent its nocturnal nature has been cast into doubt, since no known modern birds with iridescent plumage are nocturnal.[8]

Inkayacu

The melanosomes within the feathers of the Eocene penguin Inkayacu are long and narrow, similar to most other birds. Their shape suggests that Inkayacu had grey and reddish-brown feathering across its body. Most modern penguins have melanosomes that are of similar length to those of Inkayacu, but are much wider. There are also a greater number of them within living penguins' cells. The shape of these melanosomes gives them a dark brown or black color, and is the reason why modern penguins are mostly black and white. Despite not having the distinctive melanosomes of modern penguins, the feathers of Inkayacu were similar in many other ways. For instance, the feathers that made up the body contour of the species have large shafts, and the primaries along the edge of the wings are short and undifferentiated.[9]

Cruralispennia

Structures believed to be fossilized melanosomes were found in five feather samples from the only known specimen of this enantiornithean bird using scanning electron microscopy.[10] Due to their rod-like shape, they were identified as eumelanosomes, which correspond to dark shades. Although specific colors were not stated in the analysis, other studies have shown that coloration in extant birds correlates to the length and aspect ratio (length to width ratio) of their eumelanosomes.[8] A sample taken from the crural feathers had eumelanosomes with the shortest aspect ratio, which may have corresponded to dark brown coloration. The highest aspect ratio eumelanosomes were found in a sample from the head feathers. High aspect ratios have been known to correlate with glossy or iridescent colors, although without knowing the structure of a feather's keratin layer (which does not fossilize well), no hue can be assigned for certain.[8] The wing and tail samples also had high aspect ratios, while the tail's eumelanosomes were the largest sampled.[10]

Caihong

The fossilized feathers of Caihong possessed nanostructures which were analyzed and interpreted as melanosomes. They showed similarity to organelles that produce a black iridescent color in extant birds. Other feathers found on the head, chest, and the base of the tail preserve flattened sheets of platelet-like melanosomes very similar in shape to those which create brightly colored iridescent hues in the feathers of modern hummingbirds. However, these structures are seemingly solid and lack air bubbles, and thus are internally more akin to the melanosomes in trumpeters than hummingbirds. Caihong represents the oldest known evidence of platelet-like melanosomes.[11]

Non-feathered dinosaurs

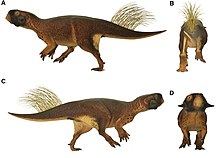

Psittacosaurus

In 2016, examination of melanosomes preserved in the integument of a specimen of Psittacosaurus sp. indicated that the animal was counter-shaded, with stripes and spots on the limbs for disruptive coloration. This is similar to that of many modern species of forest-dwelling deer and antelope and may be due to a preference for a densely forested habitat with low light. The specimen also had dense clusters of pigment on its shoulders, face (possibly for display), and cloaca (which may have had an antimicrobial function), as well as large patagia on its hind legs that connected to the base of the tail. Its large eyes indicate that it had good vision, and may be an indication of nocturnal habits.[12]

Borealopelta

In a 2017 study examination of melanosomes preserved in a specimen of Borealopelta indicated that the nodosaurid had a reddish-brown coloration in life, with a counter-shaded pattern which it was speculated was used for camouflage. The discovery that Borealopelta possessed camouflage coloration may indicate that it was under threat of predation, despite its large size, and that the armor on its back was primarily used for defensive rather than display purposes.[13]

References

- ^ Li, Q.; Gao, K.-Q.; Vinther, J.; Shawkey, M. D.; Clarke, J. A.; D'Alba, L.; Meng, Q.; Briggs, D. E. G.; Prum, R. O. (February 4, 2010). "Plumage Color Patterns of an Extinct Dinosaur" (PDF). Science. 327 (5971): 1369–1372. Bibcode:2010Sci...327.1369L. doi:10.1126/science.1186290. PMID 20133521.

- ^ Lindgren, Johan; Sjövall, Peter; Carney, Ryan M.; Cincotta, Aude; Uvdal, Per; Hutcheson, Steven W.; Gustafsson, Ola; Lefèvre, Ulysse; Escuillié, François; Heimdal, Jimmy; Engdahl, Anders; Gren, Johan A.; Kear, Benjamin P.; Wakamatsu, Kazumasa; Yans, Johan; Godefroit, Pascal (August 27, 2015). "Molecular composition and ultrastructure of Jurassic paravian feathers". Scientific Reports. 5 (1): 13520. doi:10.1038/srep13520. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4550916. PMID 26311035.

- ^ Zhang, Fucheng; Kearns, Stuart L.; Orr, Patrick J.; Benton, Michael J.; Zhou, Zhonghe; Johnson, Diane; Xu, Xing; Wang, Xiaolin (January 27, 2010). "Fossilized melanosomes and the color of Cretaceous dinosaurs and birds" (PDF). Nature. 463 (7284): 1075–1078. Bibcode:2010Natur.463.1075Z. doi:10.1038/nature08740. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 20107440.

- ^ Vinther, Jakob; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Prum, Richard O.; Saranathan, Vinodkumar (October 23, 2008). "The color of fossil feathers". Biology Letters. 4 (5): 522–525. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0302. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 2610093. PMID 18611841.

- ^ Smithwick, Fiann M.; Nicholls, Robert; Cuthill, Innes C.; Vinther, Jakob (November 2017). "Countershading and Stripes in the Theropod Dinosaur Sinosauropteryx Reveal Heterogeneous Habitats in the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota". Current Biology. 27 (21): 3337–3343.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.032. PMID 29107548.

- ^ Carney, Ryan M.; Vinther, Jakob; Shawkey, Matthew D.; D'Alba, Liliana; Ackermann, Jörg (January 24, 2012). "New evidence on the colour and nature of the isolated Archaeopteryx feather". Nature Communications. 3 (1): 637. Bibcode:2012NatCo...3E.637C. doi:10.1038/ncomms1642. PMID 22273675.

- ^ Manning, Phillip. L.; Edwards, Nicholas P.; Wogelius, Roy A.; Bergmann, Uwe; Barden, Holly E.; Larson, Peter L.; Schwarz-Wings, Daniela; Egerton, Victoria M.; Sokaras, Dimosthenis; Mori, Roberto A.; Sellers, William I. (2013). "Synchrotron-based chemical imaging reveals plumage patterns in a 150 million year old early bird". Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry. 28 (7): 1024. doi:10.1039/C3JA50077B. ISSN 0267-9477.

- ^ a b c Li, Quanguo; Gao, Ke-Qin; Meng, Qingjin; Clarke, Julia A.; Shawkey, Matthew D.; D’Alba, Liliana; Pei, Rui; Ellison, Mick; Norell, Mark A.; Vinther, Jakob (March 9, 2012). "Reconstruction of Microraptor and the Evolution of Iridescent Plumage" (PDF). Science. 335 (6073): 1215–1219. Bibcode:2012Sci...335.1215L. doi:10.1126/science.1213780. PMID 22403389.

- ^ Clarke, Julia A.; Ksepka, Daniel T.; Salas-Gismondi, Rodolfo; Altamirano, Ali J.; Shawkey, Matthew D.; D’Alba, Liliana; Vinther, Jakob; DeVries, Thomas J.; Baby, Patrice (September 30, 2010). "Fossil Evidence for Evolution of the Shape and Color of Penguin Feathers". Science. 330 (6006): 954–957. Bibcode:2010Sci...330..954C. doi:10.1126/science.1193604. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 20929737. S2CID 27415013.

- ^ a b Wang, Min; O’Connor, Jingmai K; Pan, Yanhong; Zhou, Zhonghe (January 31, 2017). "A bizarre Early Cretaceous enantiornithine bird with unique crural feathers and an ornithuromorph plough-shaped pygostyle". Nature Communications. 8: 14141. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814141W. doi:10.1038/ncomms14141. PMC 5290326. PMID 28139644.

- ^ Hu, Dongyu; Clarke, Julia A.; Eliason, Chad M.; Qiu, Rui; Li, Quanguo; Shawkey, Matthew D.; Zhao, Cuilin; D’Alba, Liliana; Jiang, Jinkai; Xu, Xing (January 15, 2018). "A bony-crested Jurassic dinosaur with evidence of iridescent plumage highlights complexity in early paravian evolution". Nature Communications. 9 (1): Article number 217. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9..217H. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02515-y. PMC 5768872. PMID 29335537.

- ^ Vinther, Jakob; Nicholls, Robert; Lautenschlager, Stephan; Pittman, Michael; Kaye, Thomas G.; Rayfield, Emily; Mayr, Gerald; Cuthill, Innes C. (September 2016). "3D Camouflage in an Ornithischian Dinosaur" (PDF). Current Biology. 26 (18): 2456–2462. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.06.065. PMC 5049543. PMID 27641767.

- ^ Brown, Caleb M.; Henderson, Donald M.; Vinther, Jakob; Fletcher, Ian; Sistiaga, Ainara; Herrera, Jorsua; Summons, Roger E. (August 2017). "An Exceptionally Preserved Three-Dimensional Armored Dinosaur Reveals Insights into Coloration and Cretaceous Predator-Prey Dynamics". Current Biology. 27 (16): 2514–2521.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.06.071. PMID 28781051.

External links

- Orange stripey dinosaurs? Fossil feathers reveal their secret colors, The Guardian, February 28, 2010

- What colour were dinosaurs?, The Guardian, February 7, 2009