Sampo (1898 icebreaker)

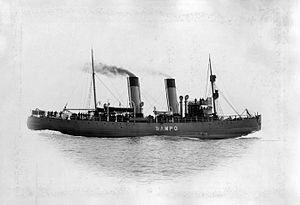

Sampo undergoing sea trials on 23 October 1898.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Sampo |

| Namesake | Magical artifact from the Finnish mythology |

| Owner | Finnish Board of Navigation[1] |

| Port of registry | Helsinki[1] |

| Ordered | 6 June 1897[2] |

| Builder | Sir W.G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom[2] |

| Cost | |

| Yard number | 679 |

| Launched | 21 April 1898 |

| Completed | 25 October 1898[3] |

| Commissioned | 15 November 1898[4] |

| Decommissioned | 9 May 1960[5] |

| In service | 1898–1960[6] |

| Fate | Broken up in 1960 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Icebreaker |

| Tonnage | |

| Displacement | 2,050 tons |

| Length | |

| Beam |

|

| Draught | 5.6 m (18.4 ft) |

| Boilers: | Five coal-fired boilers |

| Engines: | Two triple-expansion steam engines, 1,200 ihp (890 kW) (bow) and 1,400 ihp (1,000 kW) (stern) |

| Propulsion | Bow and stern propellers |

| Sail plan | Equipped with sails |

| Speed | 12.4 knots (23.0 km/h; 14.3 mph) in open water[3] |

| Crew | Initially 36,[4] later 43 |

| Armament | Armed during the Winter War with 120 mm 50 caliber Pattern 1905 guns.[7] |

Sampo was a Finnish state-owned steam-powered icebreaker. Built in 1898 by Sir W.G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd in Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom and named after a magical artifact from the Finnish mythology, she was the second state-owned icebreaker of Finland and the first European icebreaker equipped with a bow propeller. When Sampo was decommissioned and broken up in 1960, she was also the second last steam-powered icebreaker in the Finnish icebreaker fleet.

Development and construction

Prior to building Sampo, Finland had only one state-owned icebreaker, Murtaja, which was built in 1890 and was one of the first purpose-built icebreakers in the world. However, the 930-ton single-screw vessel was not powerful enough to keep even the southernmost port of Finland, Hanko, open during severe winters and the icebreaking characteristics of its spoon-shaped bow were not as good as was hoped for.[8][9] A committee, appointed by the Senate of Finland in 1895 to find a solution to the problem, came to a conclusion that a second state-owned icebreaker would be needed.[10]

In the 1890s the Senate sent two engineers and Leonard Melán, who later became the captain of Sampo, to investigate a new icebreaker design that had been developed in the United States in the 1880s and find out its icebreaking capability. Unlike the European icebreakers, the 1888-built train ferry St Ignace had two propellers, one at both end of the ship. Convinced about the superiority of the new design, the winter navigation committee recommended that the new icebreaker should be of the so-called "American type".[10]

In February 1897 the Senate sent a request for tender to eight shipbuilders for the construction of a new icebreaker. On 6 June 1897 the contract was signed with Sir W.G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd from Newcastle upon Tyne. While not the cheapest, the shipyard had the shortest delivery time — only seven months — for an icebreaker with a bow propeller.[2]

While the initial delivery date was 18 January 1898, Sampo was not delivered until October of the same year due to problems with material deliveries and strikes among the shipyard's workers. She was launched in the spring of 1898 and left for the first sea trials on 23 August. However, the bow propeller shaft seized shortly after leaving the dock and the icebreaker returned to the shipyard. The coal consumption was also 11% greater than what was specified in the contract, but instead of making changes the heating system the shipyard reduced the price by £700. The second sea trial on 21 September was successful and Sampo left for Finland on 25 October 1898 and arrived to Helsinki four days later.[3]

Career

Early career

Sampo was officially commissioned on 15 November 1898 and began assisting ships outside the port of Hanko while the smaller Murtaja was stationed closer to the harbour. From the first day on the new icebreaker, capable of breaking through ridges up to six metres thick by ramming, performed beyond expectations and was generally deemed the best icebreaker in Europe at that time. On 9 March 1899, her performance was demonstrated to the director of the Finnish Pilot and Lighthouse Authority when both state-owned icebreakers headed to the sea, Murtaja running in a previously opened channel and Sampo alongside in unbroken ice. However, on the way back to the port Sampo, followed by Murtaja, encountered a thick ice ridge and came to a halt. The smaller icebreaker could not stop in time and collided with Sampo, causing damage to her stern structures but fortunately no injuries to the passengers. Sampo ended her first winter season on 16 May 1899, during which she had assisted 128 ships.[4]

The first decade of Sampo passed without major incidents. In 1907, another icebreaker with a bow propeller, Tarmo, was ordered from the builders of Sampo.[11]

First World War

In August 1914 Russia joined the First World War and navigating in the Baltic Sea became dangerous due to naval mines and German U-boats. The Finnish icebreakers were placed under the command of the Baltic Fleet of the Imperial Russian Navy and given the task of assisting naval ships and troop transportations in the Gulf of Finland. Unlike Tarmo, Sampo was not armed with a deck gun. Icebreaker assistance to merchant ships was largely neglected.[12] Sampo survived the war without damage.

On 6 December 1917 the Parliament of Finland accepted the declaration of independence given by the Senate and on 29 December the icebreakers Murtaja and Sampo raised the state flag of the independent Finland for the first time.[13] However, already in early January 1918 the ship was seized by the Russian revolutionary fleet and ordered to assist the Russian troops stationed in Finland. The White Guards in Korpo and Nagu attempted to retake Sampo later in January but failed.[14]

Finnish Civil War

On 27 January 1918 the Red Guard took over Helsinki and the Finnish Civil War began.[14] However, on the same day Sampo managed to escape to Sweden and join the Whites. The Russian commissar who was on board at the time was taken into custody and left on ice outside the port of Pori before the icebreaker headed for Gävle to wait for further orders.[15]

Sampo had a significant impact on the outcome of the Civil War when it assisted three convoys to the White-controlled ports in northern Finland. The ships brought more than a thousand Jägers, Finnish volunteers trained in Germany, and enough weapons for the whole White Guard. The first convoy left Danzig on 11 February 1918 and was picked up by Sampo three days later outside the island of Märket. The steamships Mira and Poseidon, owned by the Finland Steamship Company and carrying 85 Jägers and weapons for the Finnish troops, arrived at Vaasa on 18 February. On 20 February, Sampo encountered the second convoy in the Stockholm archipelago. The ships, passenger steamship Arcturus and cargo steamer Castor, had left Libau on 14 February with the bulk of the troops, 950 Jägers, and some 1,200 tons of coal. Castor was left outside Gävle while Arcturus was escorted through difficult ice conditions to Vaasa, where it arrived on 25 February in the midst of a large crowd of cheering people. The last ship, Virgo, left Neufahrwasser on 20 February with 25 soldiers and full cargo of weapons, and was assisted to Vaasa on 2 March.[15]

On 4 April, while heading out from the port of Hanko with German warships, the convoy led by Sampo encountered another Finnish icebreaker, Murtaja, coming from Utö with the steamship Dragsfjärd. Both ships were filled with Red Guard and Russian soldiers, but after several warning shots from the German naval vessels most of the enemy soldiers fled on ice and Murtaja was taken over by the Whites.[15]

Sampo arrived to Helsinki for the summer on 12 May 1918, three days before the Civil War ended to decisive White victory.[15]

Interwar period

While Sampo had not been damaged in the war, she was docked at the Hietalahti shipyard for extensive maintenance and repairs — when she left to the port of Hanko in mid-February 1919, 69 bottom plates had been replaced.[16] In December 1922 Sampo struck a rock in the port of Loviisa and her bow propeller shaft was damaged, but there was no time for repairs and for the rest of the season she had to assist ships to the port of Helsinki without her bow propeller.[17] Another incident occurred on 24 March 1926 when the bow propeller of Sampo hit a stone bank in the port of Helsinki, came loose and dropped to the bottom. It was found after searching for a couple of days and winched on board. On 30 March, while Sampo was assisting a Finnish steamship Albert Kasimir, the stern propeller shaft snapped when the engine was reversed and the propeller dropped to the bottom. While the icebreaker still had its bow propeller, it was of no use as it was waiting for installation on the foredeck. Murtaja towed the immobilized icebreaker to Hanko on the following day and to Helsinki for repairs on 20 April.[18]

Between 1919 and 1922 Sampo assisted 636 ships, more than any other Finnish icebreaker during that time.[17] In the 1920s the need for new icebreakers was recognized and two new steam-powered icebreakers were built.[6] From 1926 on Sampo and Tarmo began their winter season from the eastern parts of the Gulf of Finland, assisting ships to Koivisto, Viipuri and Kotka, and moved to western ports as the harbours were closed for winter.[19] In 1929 the whole Baltic Sea was frozen and Sampo was sent to the Danish straits for two months.[20]

Winter War

Due to the worsening relations with the Soviet Union, Sampo and other state-owned icebreakers were armed and assigned to a wartime icebreaker fleet shortly before the Winter War began on 30 November 1939. The Finnish icebreakers had been equipped with gun mounts already in the 1920s and were armed with light artillery. However, a bit over month into the war Sampo ran hard aground and was out of service for more than a year.[21]

On 6 January 1940 Sampo was assisting a convoy of three merchant ships towards Pori in difficult conditions — the temperature was nearly −30 °C (−22 °F) and fog reduced the visibility to zero. The icebreaker was proceeding in light ice conditions at 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) when she collided with an underwater obstacle and suddenly stopped, throwing the helmsman through the wheelhouse windows and damaging the ship's radio antennas. The collision had damaged the forward steam engine and propeller shaft, and Sampo was resting high on the rocks with the bow propeller above the water.[22]

The first rescue attempts were made on the following day when two tugboats tried to turn the stern of Sampo towards open water together with the icebreaker's own engine and rudder. However, the task was deemed impossible and the tugboats evacuated the pilot and the women working in the icebreaker's kitchen to Mäntyluoto. On 8 January Sampo was further damaged when the wind pushed a large ice floe against the side of the icebreaker and the waves began pounding her hull against the rocks. Both engine rooms flooded and the pumps stopped. In the following night Sampo slowly settled in the bottom, listing the partially submerged icebreaker approximately 20 degrees starboard. The remaining crew members were evacuated in heavy weather and freezing temperatures on the following day. The salvaging Sampo was awarded to the Finnish salvage company Neptun Oy, but the task was deemed impossible in the presence of ice.[22]

While waiting for the spring thaw, Sampo was camouflaged with tree branches to resemble a small island. This was not very successful, because during the last weeks of the Winter War the Soviet bombers made several attempts to destroy the ship. However, despite dropping at least 250 bombs on the grounded icebreaker the enemy pilots never scored a hit.[22]

The Winter War ended on 13 March 1940 with Sampo still grounded outside Pori.[23]

Interim peace

Neptun began salvaging the grounded Sampo in May 1940 by emptying the coal storages and melting the ice masses inside the vessel with steam. The icebreaker was towed to Turku in June because the longer distance to Helsinki was deemed too risky — large stones had wedged between the mangled bottom plating, and had they fallen during the transit, Sampo would have filled with water and sunk. The icebreaker arrived in Turku on the Midsummer Eve of 1940 and after emergency repairs was towed to Hietalahti shipyard in Helsinki, where it remained for extensive repairs until 13 March 1941.[23]

The Second World War

Continuation War

When the Continuation War began on 25 June 1941, the Finnish icebreakers were re-armed and their anti-aircraft armament was improved. The winter of 1942 was the worst since the 1740s and Sampo was sent to assist ships stuck in ice all the way to the Gulf of Riga. The following winters were much milder and Sampo survived the war without major incidents.[24]

In 1946, after the war had ended to the Moscow Armistice, the Allied Control Commission ordered Sampo to assist ships in the Soviet port of Leningrad.[25]

Post-war years

After the newest and most powerful state-owned icebreakers, Voima and Jääkarhu, were handed over to Soviet Union as war reparations, Finland was left with four old steam-powered icebreakers and the small diesel-electric Sisu, which had been rejected due to the extensive damage it had sustained in the war.[26] The newest steam-powered icebreaker, Tarmo, was almost 40 years old and along with the others long overdue for replacement — even the largest Finnish icebreakers were not wide and powerful enough to assist the biggest post-war cargo ships. There was also a severe shortage of coal and occasionally the Finnish icebreakers had to rely on firewood.[27] The steam-powered icebreakers were completely overhauled for the last time in 1951–1952 when they finally received modern navigation equipment — even as late as 1952 some had neither gyrocompass, sonar nor radar — and their crew spaces were rebuilt to modern standards.[28] There were talks about converting the furnaces of Sampo from coal to oil, but it was not deemed necessary as the old icebreaker was due to decommissioning in the near future.

Once the war reparations to the Soviet Union had been paid in 1952, Finland started renewing its icebreaker fleet. The first state-owned icebreaker built after the Second World War, diesel-electric Voima, was delivered in 1954 as a replacement for Jääkarhu.[29] During the winter of 1956, the coldest of the decade, the new icebreaker assisted, among other ships, the old steam-powered icebreakers — Sampo had even ran out of coal while attempting to free herself after having been immobilized by the severe ice conditions.[30]

Decommissioning

When the harsh winters of the 1950s showed that more modern icebreakers were needed, a series of slightly smaller diesel-electric icebreakers were built for operations within the archipelago. Karhu replaced Murtaja in 1958, the new Murtaja replaced Apu in 1959 and the new diesel-electric Sampo replaced the old steam-powered one in 1960.[31]

One of the last tasks of the old icebreaker was to tow the recently decommissioned full rigged training ship Suomen Joutsen from Porkkala to Turku, where the three-masted frigate would be converted to a Seamen's School for the Finnish Merchant Navy, on 15–17 January 1960. Sampo was decommissioned shortly afterwards, on 9 May. The last Finnish steam-powered icebreaker, Tarmo, remained in service until 1970.[31]

While initially there were talks about saving Sampo and turning her into a museum ship, the cultural and historical importance of the old steam-powered icebreaker was not recognized at that time and the 62-year-old ship was sold for scrap. She was broken up on a small shipyard in Mathildedal in Southwest Finland.[32] Her wooden wheel was salvaged and put on display in the main office of the Finnish Maritime Administration, and the wooden paneling and furniture of the salon was bought by the Finnish yacht club Suomalainen Pursiseura for their club restaurant in Sirpalesaari, Helsinki. In addition the bow propeller shaft of Sampo serves the Finnish winter navigation to this day as part of a sea mark on a small skerry southeast from the island of Utö.[31]

Technical details

Sampo was 61.40 metres (201.44 ft) long overall and 58.35 metres (191.44 ft) at the waterline. Her moulded breadth was 13.00 metres (42.65 ft) and breadth at the waterline slightly smaller, 12.80 metres (41.99 ft). The draught of the icebreaker at maximum displacement, 2,050 tons, was defined in the contract as 17 feet 3 inches (5.26 m) in the bow and 18 feet 3 inches (5.56 m) in the stern.[2][6] She was initially operated by a crew of 36, but this was later increased by two divers and additional stokers.[33]

The hull of Sampo was built of Siemens-Martin steel and divided into watertight compartments by eight transverse bulkheads. The bow was reinforced with a wide ice belt up to one inch (2.5 cm) thick and all steel structures were dimensioned beyond Lloyd's Register requirements.[2] The angle of the stem, the first part of the icebreaker to encounter ice and bend it under the weight of the ship, was 24 degrees.[6] Other innovative features included propeller blades that could be replaced underwater by the icebreaker's divers.

Sampo was powered by two triple-expansion steam engines, one driving a propeller in the stern and the other a second propeller in the bow. The main function of the bow propeller was to reduce friction between the hull and the ice, although the exact details of the icebreaking process were not known at that time.[10] The stern engine produced 1,600 ihp at 110 rpm and the bow engine 1,400 ihp at 115 rpm.[6] During the sea trials the maximum indicated output of the two steam engines was 3,052 ihp and when the engines were producing 2,500 ihp, the icebreaker could maintain a speed of 12.4 knots in open water.[3] Sampo had five coal-fired boilers for the main engines in two boiler rooms and a small auxiliary boiler for heating, deck equipment and light generator in the foremost boiler room.[2] The fuel stores could hold 350 tons of coal that was fed to the fireboxes at a rate of 2.4–3.2 tons per hour.[6] Like all icebreakers of her age, Sampo was also equipped with sails although they were rarely, if ever, used.[34]

Sampo was equipped for escort icebreaker duties with a towing winch, a cable and a stern notch. In difficult ice conditions the ship being assisted was taken into tow, and in extremely difficult compressive ice it was pulled to the icebreaker's stern notch.[35] For salvage operations Sampo had a powerful centrifugal pump capable of pumping 700 tons of water per hour.[2]

Notes

- ^ a b c d Lloyd's Register of Ships, 1930-1931.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Laurell 1992, p. 58-59.

- ^ a b c d e Laurell 1992, p. 60-61.

- ^ a b c Laurell 1992, p. 64-65.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 334.

- ^ a b c d e f Laurell 1992, p. 344.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 259.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 30.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 44.

- ^ a b c Laurell 1992, p. 52-56.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 72-73.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 91-93.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 99.

- ^ a b Laurell 1991, p. 100-101.

- ^ a b c d Laurell 1992, p. 103-107.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 121-122.

- ^ a b Laurell 1992, p. 131-132.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 156-157.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 158-159.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 176.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 259-260.

- ^ a b c Laurell 1992, p. 263-265

- ^ a b Laurell 1992, p. 277.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 282-291.

- ^ Kaukiainen 1992, p. 226.

- ^ Kaukiainen 1992, p. 165.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 304.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 315.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 318.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 320, 330

- ^ a b c Laurell 1992, p. 330-335.

- ^ Sipilä, P. Romutuksia ja uudisrakenteita Teijon telakalla. Laiva 1/2001.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 291.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 77.

- ^ Laurell 1992, p. 198-200.

References

Kaukiainen, Yrjö (1992). Navigare Necesse - Merenkulkulaitos 1917–1992. Jyväskylä: Gummerus Kirjapaino Oy. ISBN 951-47-6776-4.

Laurell, Seppo (1992). Höyrymurtajien aika. Jyväskylä: Gummerus Kirjapaino Oy. ISBN 951-47-6775-6.