Amelia Van Buren

Amelia Van Buren | |

|---|---|

Van Buren, c. 1891 | |

| Born | c. 1856 Detroit, Michigan |

| Died | 1942 |

| Resting place | Tryon Cemetery, Tryon, North Carolina |

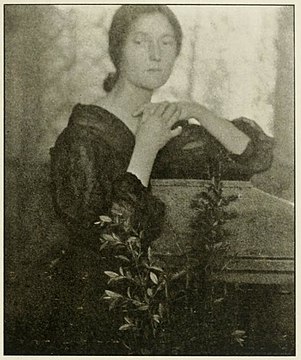

Amelia C. Van Buren (c. 1856[N 1] – 1942) was an American photographer. A noted portrait photographer, she was a student of Thomas Eakins, and the subject of his c. 1891 painting Miss Amelia Van Buren, regarded as one of his finest works.

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

Van Buren was born in Detroit, Michigan. Both her parents died sometime prior to 1884, when she began attending the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.[3]: 347–48 She had already been exhibiting her artwork in Detroit for at least four years prior to attending the Academy.

Her talent soon led Eakins to tutor her personally, including controversial lessons using nude models, male and female.[2]: 127 In 1885–86, several of Eakins's former art students (including Thomas Pollock Anshutz and Colin Campbell Cooper) conspired to have Eakins fired from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. They approached the Academy's Committee on Instruction, and made numerous charges against Eakins. They alleged that Eakins had used female students, including Van Buren, as nude models. Another highly inflammatory charge was that Van Buren had asked Eakins a question regarding pelvic movements, which Eakins answered by removing his pants and demonstrating the movements. He later insisted that the episode was completely professional in nature.[3]: 116 The committee left Eakins under the impression that the charges had been filed by Van Buren, who had moved to Detroit to recover from neurasthenia.[4] That, however, was not the case, as she greatly respected Eakins and in years to come would defend him at every opportunity, as well as express pride in owning pieces of his artwork.[5]: 323

After recovering, Van Buren returned to Philadelphia, where she continued in her studies under Eakins at the Art Students' League of Philadelphia. Van Buren and Eakins stayed in close contact for a number of years afterward. Three or four years after his dismissal, Eakins painted Van Buren in Miss Amelia Van Buren.

Post-Academy

There is little information on Van Buren's life and professional career following her education at the Academy. No paintings by Van Buren are known to survive.[3]: 348

She entered into a Boston marriage with fellow student Eva Watson-Schütze. The two of them opened a studio and art gallery in Atlantic City, New Jersey, but Van Buren disliked having to make compromises in her aesthetic sense to sell any paintings, so she turned to photography instead.[6] Both women were recognized as accomplished artists and exhibited together at the Camera Club of Pittsburgh in 1899,[7] and Van Buren was noted for her portraits, once declaring her goal was to make portraits "to stand with [those of] Sargent and Watts and the other masters".[8]

It is known that by 1900, when she sent some prints to Frances Benjamin Johnston, she had moved back to Detroit.[7] She had the portrait of herself in her possession, likely a gift from the artist himself, which she sold to the Phillips Memorial Gallery in 1927,[9] by which time she was living in North Carolina.[10]

In the early 1930s Lloyd Goodrich, who was writing the first full-length biography of Eakins, wrote to Van Buren. However, she replied that she had no particular reminiscences of Eakins.[3]: 348 Van Buren spent her later years in an artists' colony in Tryon, North Carolina, where she died in 1942.[5]: 422

Works by Van Buren

-

Portrait of a woman in a dress, c. 1900

-

Study of a head, c. 1900

-

Mother and Child, c. 1901

-

Isabella, ca. c. 1903

Notes

References

- ^ "Tryon Cemetery, Section 1". USGenWeb. Archived from the original on September 7, 2010. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- ^ a b Dixon, Laurinda S.; Weisberg, Gabriel P. (2004). In sickness and in health: disease as metaphor in art and popular wisdom. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 978-0-87413-857-3.

- ^ a b c d Adams, Henry (2005). Eakins revealed: the secret life of an American artist. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-515668-3.

- ^ Sewell, Darrel (2001). Thomas Eakins. Yale University Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-87633-143-9.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick, Sidney (2006). The revenge of Thomas Eakins. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10855-2.

amelia van buren.

- ^ Sandler, Martin W. (2002). Against the Odds: Women Pioneers in the First Hundred Years of Photography. Rizzoli International Publications. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-0-8478-2304-8.

- ^ a b Rosenblum, Naomi (1994). A History of Women Photographers. Abbeville Press. p. 323. ISBN 978-1-55859-761-7.

- ^ Cotkin, George (2004). Reluctant modernism: American thought and culture, 1880–1900. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-3147-5.

- ^ "Eakins in the Collection". The Phillips Collection. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ Wilmerding, John (1993). Thomas Eakins. Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-56098-313-2.

Further reading

- Clark, William J. (1991). "The Iconography of Gender in Thomas Eakins' Portraiture". American Studies. 32 (2): 5–28.

- Davidov, Judith Fryer (1998). Women's camera work: self/body/other in American visual culture. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Kirkpatrick, Sidney D. (2006). The Revenge of Thomas Eakins. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 379–387.

External links

Media related to Amelia Van Buren at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Amelia Van Buren at Wikimedia Commons