Shishugou Formation

| Shishugou Formation | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Callovian-Oxfordian ~ | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Qigu Group |

| Sub-units | Wucaiwan Member |

| Underlies | Kalaza Formation |

| Overlies | Xishanyao Formation[1] |

| Thickness | 380 m (1,250 ft) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Mudstone |

| Other | Tuff, sandstone, conglomerate |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 44°30′N 90°12′E / 44.5°N 90.2°E |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 42°30′N 100°30′E / 42.5°N 100.5°E |

| Region | Xinjang |

| Country | |

| Extent | Northern Junggar Basin |

The Shishugou Formation (simplified Chinese: 石树沟组; traditional Chinese: 石樹溝組; pinyin: Shíshùgōu Zǔ) is a geological formation in Xinjiang, China.

Its strata date back to the Late Jurassic period. Dinosaur remains are among the fossils that have been recovered from the formation[2] (see Junggar Basin dinosaur trap). The Shishugou Formation is considered one of the most phylogenetically and trophically diverse Middle to Late Jurassic theropod fauna.[3]

The Wucaiwan Member, once considered a separate, underlying formation,[4] is now considered the lowest unit of the Shishugou Formation.

Lithology

At the Wuwaican locality, the formation is approximately 380 m thick, the lower 30 metres of the formation predominantly consist of conglomerate, with the majority of the formation consisting of red coloured mudstone with frequent channel/sheet sandstone lenses and occasional tuffaceous deposits.[3] It is laterally equivalent to the Qigu Formation in the southern half of the Junggar Basin.

Shishugou Formation dinosaur traps

The Shishugou Formation dinosaur traps also known as death pits or death traps are pit structures found within the formation that are noted for their fossil content.

Paleontology

These 'traps' or 'bonebeds' are unusual in that they consist of vertically stacked skeletons of numerous non-avian theropods in 1–2 metres (3.3–6.6 ft) deep pits. The pits are filled with a mix of alluvial and volcanic mudstone and sandstone and appear to have been created by the trampling and wallowing of large dinosaurs. Small theropods and vertebrates then became mired in these pits, dying and being forced deeper by the activities of the large dinosaurs and the struggles of later victims. The high quality of preservation suggests a rapid burying of the carcasses. Some scavenging of the bodies took place leading to a dispersal of body parts. Smaller vertebrates were prone to getting stuck in these mudholes, and the small ceratosaur, Limusaurus inextricabilis, is the most common in the resulting bonebeds.[5]

Excavations since 2000 have revealed a wealth of fossils dating from a period some 165 to 155 million years ago. Palaeontologists James Clark and Xu Xing are shedding light on this period previously notorious for its paucity of fossils, but important for its massive burst of speciation among the dinosaurs and ancestors of birds. These new branches on the dinosaur family tree led to well-known dinosaur groups, such as the horned ceratopsians, armoured stegosaurs, and tyrannosaurs. Clark joined Xu, from Beijing’s Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, to explore the Junggar Basin, and in particular the Shishugou Formation, where the exposed rocks have been linked to the Middle Jurassic.

Prehistoric life

At the time the area was covered by marshland, adjoined a small mountain range peppered with volcanoes, and was inhabited by dinosaurs, small crocodilians and amphibians. Currently it is a sparsely settled region of dry washes, arid badlands and dunes along the Gobi desert’s western edge. The Shishugou Formation consists of mudstone, siltstone, and sandstone, and is named for the silicified wood or petrified logs found here. ('Shishugou' = 'stone tree valley') These badlands were used for some sequences in the film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon,[6] the genus Yinlong ('hidden dragon') being named for the film.

When the site was first excavated, new species of turtles, crocodilians, pterosaurs, and early mammals were revealed. Many of these species showed the rudiments of characteristics that would later become their hallmarks. One of the first fossil skeletons exposed proved to be that of an unknown theropod, and revealed a stack of four more theropods buried below the first. Yang Zhongjian accompanied the first expedition to the Junggar Basin in 1928, and the fossils found included the medium-size sauropod Tienshanosaurus chitaiensis. Later expeditions stretched from the 1960s to the 1990s and yielded among others the extremely long-necked Mamenchisaurus and the carnivorous Sinraptor. In all, some 600 specimens have been collected.

On analysis of the rock matrix, large amounts of volcanic ash were found, hinting at eruptions during that period, the ash raining onto the marsh creating viscous mud and becoming subsequent death traps. To date three of these death pits have been located. In one pit a crocodilian was found against a small ceratosaur, in another three decapitated ceratosaurs. The most interesting of the traps gave up the fossil remains of an 80 kg tyrannosauroid named Guanlong, sporting a crest running from its nose to the back of its head. Its discovery was hailed by paleontologists as the earliest known remains of the tyrannosauroid clan that culminated with Tyrannosaurus rex.

Fauna

Ornithischians

Undescribed stegosaur is present in the Wucaiwan member.[4] Undescribed ornithopod is present in the Wucaiwan member.[4] Undescribed ankylosaurs present in both upper Shishugou and Wucaiwan members.[2]

| Genus | Species | Stratigraphic position | Abundance | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Eugongbusaurus" |

"Eugongbusaurus wucaiwanensis" |

An unspecified basal ornithopod (or perhaps a more basal neornithischian), previously classified as Gongbusaurus wucaiwanensis.[2] It is estimated at around 1.3 to 1.5 meters (4.3 to 4.9 ft) long. |

| ||

|

Jiangjunosaurus junggarensis |

A stegosaur reaching around 6 meters (20 feet) in length and weighed 2.5 tonnes.[7] It had three distinguishing traits: the crowns of the teeth are symmetrical and in side view wider than tall; the spine of the axis, the second neck vertebra, has a rectangular profile in side view, instead of a triangular one; and the rear neck vertebrae have large vein openings in their sides. | ||||

|

Yinlong downsi |

A very basal and most primitive ceratopsian. It was bipedal and had a total length of about 1.2 meters (3.9 feet) from nose to tail, and a weight of about 15 kilograms (33 pounds).[8] |

Pterosaurs

| Genus | Species | Stratigraphic position | Abundance | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

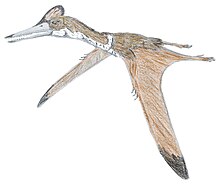

|

Kryptodrakon progenitor |

A basal pterodactyloid with an estimated wingspan of 1.47 meters (4.8 feet). |

| |||

|

Sericipterus wucaiwanensis |

A rhamphorhynchine rhamphorhynchid with a wingspan that has been estimated at least 1.73 meters.[9] |

Sauropods

| Sauropods reported from the Shishugou Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images | |

|

Bellusaurus sui |

Wucaiwan member |

A short-necked camarasaurid which measured about 4.8 meters (16 feet) long.[4] |

| |||

| F. qitaiensis | Complete right femur |

A titanosauriform sauropod | ||||

|

Klamelisaurus gobiensis |

Wucaiwan member |

A eusauropod measuring 15 meters and weighing 5 tonnes. It is similar to Bellusaurus, of which it may actually be an adult specimen and thus a junior synonym.[4] | ||||

|

Mamenchisaurus sinocanadorum |

"Partial skull and skeleton."[11] |

A mamenchisaurid with a remarkably long neck which made up half the total body length.[2] It is one of the largest dinosaurs known, measuring 35 meters (115 feet) in length with an 18-meter-long (59 feet) neck. | ||||

|

Tienshanosaurus chitaiensis |

"Partial postcranial skeleton."[12] |

A mamenchisaurid known from very few remains.[2] | ||||

Theropods

Undescribed ornithomimosaur-like species.[2] Indeterminate tetanuran remains.[2]

| Genus | Species | Stratigraphic position | Abundance | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A. zhaoi |

Wucaiwan member |

An unspecified basal tyrannoraptoran that was at best 1 meter (3.3 feet) long and weighed 2 kilograms (4.4 pounds) at most.[3] |

| ||

|

Guanlong wucaii |

A proceratosaurid that was one of the earliest tyrannosaurs, about 3 meters (9.8 feet).[13] It has a large distincitve crest on its head, a feature seen in many primitive tyrannosaurs. | ||||

|

Haplocheirus sollers |

An alvarezsaur that was the largest known definite member of the superfamily, at around 2 meters long. It had an enlarged thumb claw like other alvarezsaurs, but also retained two other functional fingers, unlike more derived alvarezsaurs, where only the thumb was significantly large and clawed.[14] | ||||

|

Limusaurus inextricabilis |

A primitive, toothless, herbivorous elaphrosaurine noasaur that is the first definitely known ceratosaur from Eastern Asia, including China, as well as one of the earliest.[15] Limusaurus had a small slender body measuring about 1.7 meters in length. | ||||

|

Monolophosaurus jiangi |

Wucaiwan member |

A tetanuran named for the single crest on top of its skull. It is estimated to have a length at 5.5 meters (16.4 feet), the weight at 475 kilograms. | |||

|

Shishugounykus inexpectus |

An early Alvarezsauroid. | ||||

|

Sinraptor dongi |

A metriacanthosaur theropod standing nearly 3 meters (9.8 feet) tall and measuring roughly 7.6 meters (25 feet) in length. | ||||

|

Zuolong salleei |

A basal coelurosaur approximately 3 meters (9.8 feet) long, and weighs about equal to a gray wolf. The specimen known is probably from a juvenile individual, and is quite complete.[16] |

Mammaliamorphs

| Genus | Species | Stratigraphic position | Abundance | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuanotherium | Y. minor | Upper | A tritylodontid[17] |

See also

References

- ^ Vincent SJ; Allen MB (2001). "Sedimentary record of Mesozoic intracontinental deformation in the eastern Juggar Basin, northwest China: response to orogeny at the Asian margin". In Hendrix MS; Davis GA (eds.). Paleozoic and Mesozoic Tectonic Evolution of Central and Eastern Asia. Colorado, US: The Geological Society of America, Inc. pp. 354–356. ISBN 978-0813711942.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Weishampel, David B; et al. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution (Late Jurassic, Asia)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 550–552. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ^ a b c Choiniere JN; Clark JM; Forster CM; Norell MA; Eberth DA; Erickson GM; Chu H; Xu X (2013). "A juvenile specimen of a new coelurosaur (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Middle–Late Jurassic Shishugou Formation of Xinjiang, People's Republic of China". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. online (2): 177. doi:10.1080/14772019.2013.781067.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c d e Weishampel, David B; et al. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution (Middle Jurassic, Asia)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 541–542. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ^ "Dinosaur Deathpits from the Jurassic of China"

- ^ China's Junggar Basin - National Geographic

- ^ Chengkai, Jia; Forster, Catherine A; Xing, Xu; Clark, James M. (2007). "The first stegosaur (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the Upper Jurassic Shishugou Formation of Xinjiang, China". Acta Geologica Sinica (English Edition). 81 (3): 351–356. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2007.tb00959.x.

- ^ Xu, X.; Forster, C.A.; Clark, J.M.; Mo, J. (2006). "A basal ceratopsian with transitional features from the Late Jurassic of northwestern China". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 273 (1598): 2135–2140. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3566. PMC 1635516. PMID 16901832.

- ^ Andres, B.; Clark, J. M.; Xing, X. (2010). "A new rhamphorhynchid pterosaur from the Upper Jurassic of Xinjiang, China, and the phylogenetic relationships of basal pterosaurs" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (1): 163–187. doi:10.1080/02724630903409220.

- ^ "A new titanosauriform dinosaur (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from Late Jurassic of Junggar Basin, Xinjiang (In Chinese)". Global Geology. 38: 581–588. 2019.

- ^ "Table 13.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 262.

- ^ "Table 13.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 271.

- ^ Xu X., Clark, J.M., Forster, C. A., Norell, M.A., Erickson, G.M., Eberth, D.A., Jia, C., and Zhao, Q. (2006). "A basal tyrannosauroid dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of China". Nature. 439 (7077): 715–718. Bibcode:2006Natur.439..715X. doi:10.1038/nature04511. PMID 16467836.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Choiniere, J. N.; Xu, X.; Clark, J. M.; Forster, C. A.; Guo, Y.; Han, F. (2010). "A basal alvarezsauroid theropod from the Early Late Jurassic of Xinjiang, China". Science. 327 (5965): 571–574. Bibcode:2010Sci...327..571C. doi:10.1126/science.1182143. PMID 20110503.

- ^ Xu, X.; Clark, JM; Mo, J; Choiniere, J; Forster, CA; Erickson, GM; Hone, DW; Sullivan, C; et al. (2009). "A Jurassic ceratosaur from China helps clarify avian digital homologies" (PDF). Nature. 459 (7249): 940–944. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..940X. doi:10.1038/nature08124. PMID 19536256.

- ^ Jonah N. Choiniere, James M. Clark, Catherine A. Forster and Xing Xu (2010). "A basal coelurosaur (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Jurassic (Oxfordian) of the Shishugou Formation in Wucaiwan, People’s Republic of China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (6): 1773–1796. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.520779.

- ^ Yaoming Hu, Jin Meng & James M. Clark (2009). "A new tritylodontid from the Upper Jurassic of Xinjiang, China" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 54 (3): 385–391. doi:10.4202/app.2008.0053.

- Geologic formations of China

- Geologic formations of Mongolia

- Jurassic System of Asia

- Jurassic China

- Jurassic Mongolia

- Callovian Stage

- Oxfordian Stage

- Mudstone formations

- Sandstone formations

- Tuff formations

- Fluvial deposits

- Lacustrine deposits

- Paludal deposits

- Fossiliferous stratigraphic units of Asia

- Paleontology in Xinjiang