Malik Muhammad Jayasi

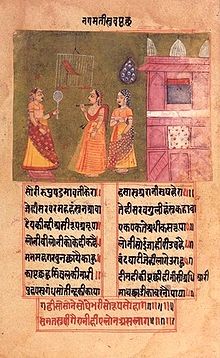

Malik Muhammad Jayasi (1477– 1542) was an Indian Sufi poet and pir.[1] He wrote in the Awadhi language, and in the Persian Nastaʿlīq script.[2] His best known work is the epic poem Padmavat (1540).[3]

Biography

Much of the information about Jayasi comes from legends, and his date and place of birth are a matter of debate. As the nisba "Jayasi" suggests, he was associated with Jayas, an important Sufi centre of medieval India, in present-day Uttar Pradesh. However, there is debate about whether he was born in Jayas, or migrated there for religious education.[4]

The legends describe Jayasi's life as follows: he lost his father at a very young age, and his mother some years later. He became blind in one eye, and his face was disfigured by smallpox. He married and had seven sons. He lived a simple life until he mocked the opium addiction of a pir (Sufi leader) in a work called Posti-nama. As a punishment, the roof of his house collapsed, killing all seven of his sons. Subsequently, Jayasi lived a religious life at Jayas.[4] He is also said to have been raised by Sufi ascetics (fakir).[1]

Jayasi's own writings identify two lineages of Sufi pirs who inspired or taught him. The first lineage was that of the Chishti leader Saiyid Ashraf Jahangir Simnani (died 1436–37) of Jaunpur Sultanate: according to tradition, Jayasi's teacher was Shaikh Mubarak Shah Bodale, who was probably a descendant of Simmani. The second lineage was that of Saiyid Muhammad of Jaunpur (1443-1505). Jayasi's perceptor from this school was Shaikh Burhanuddin Ansari of Kalpi.[5]

Jayasi composed Akhiri Kalam in 1529-30 (936 AH), during the reign of Babur. He composed Padmavat in 1540-41 (936 AH).[4]

Some legends state that Raja Ramsingh of Amethi invited Jayasi to his court, after he heard a mendicant reciting verses from the Padmavat. One legend states that the king had two sons because of Jayasi's blessings. Jayasi spent the later part of his life in forests near Amethi, where he would often turn himself into a tiger. One day, while he was roaming around as a tiger, the king's hunters killed him. The king ordered a lamp to burned and Quran to be recited at his memorial.[4]

Though his tomb lies in a place 3 km north of Ram Nagar, near Amethi, where he died in 1542, today a "Jaisi Smarak" (Jaisi Memorial) can be found in the city of Jais.

Legacy

More than a century after his death, Jayasi's name started appearing in hagiographies that portrayed him as a charismatic Sufi pir. Ghulam Muinuddin Abdullah Khweshgi, in his Maarijul-Wilayat (1682–83), called him muhaqqiq-i hindi ("knower of the truth of al-Hind").[4]

Literary works

He wrote 25 works.[1] Jayasi's most famous work is Padmavat (1540),[6] a poem describing the story of the historic siege of Chittor by Alauddin Khalji in 1303. In Padmavat, Alauddin attacks Chittor after hearing of the beauty of Queen Padmavati, the wife of king Ratansen.[7]

His other important works include Akhrawat and Akhiri Kalaam. He also wrote Kanhavat, based on Krishna.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d "Padmini's poet: The man behind the first known narrative of Rani Padmavati is known more as a peer". The Indian Express. 26 November 2017.

- ^ Ramya Sreenivasan 2007, p. 30.

- ^ Garg, Gaṅgā Rām (1992). Encyclopaedia of the Hindu World. Concept Publishing Company. p. 73. ISBN 9788170223740.

- ^ a b c d e Ramya Sreenivasan 2017, p. 28.

- ^ Ramya Sreenivasan 2017, p. 29.

- ^ "Absurdity of epic proportions: Are people aware of the content in Jayasi's Padmavat?".

- ^ Aditya Behl 2012, pp. 166–176.

Bibliography

- Aditya Behl (2012). Love's Subtle Magic: An Indian Islamic Literary Tradition, 1379–1545. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514670-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ramya Sreenivasan (2007). The Many Lives of a Rajput Queen: Heroic Pasts in India C. 1500–1900. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98760-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Malik Muhammad Jayasi at Kavita Kosh (in Hindi)