The Tragical History of Guy Earl of Warwick

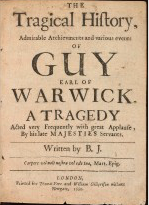

| The Tragical History, Admirable Atchievments and Various Events of Guy Earl of Warwick | |

|---|---|

| Written by | "B.J." |

| Original language | English |

| Genre | History |

| Setting | Europe and the Holy Land |

The Tragical History of Guy Earl of Warwick or The Tragical History, Admirable Atchievments and Various Events of Guy Earl of Warwick (Guy Earl of Warwick) is an English history play, with comedy, of the late 16th or early 17th century. The author of Guy Earl of Warwick is not known, although Ben Jonson and Thomas Dekker have been proposed. The play is about the adventures of legendary English hero Guy of Warwick in Europe and the Holy Land, and about the relationship between Guy and his wife, Phillis. Guy Earl of Warwick is notable because one of the characters - Guy's servant and comic sidekick Philip Sparrow - is considered by some scholars to be an early lampoon of William Shakespeare.

Date of Composition

Based on the structure of the play, topical allusions, and subject matter concerning "Christian piety and the cardinal virtues," Shakespeare scholar Alfred Harbage concludes that Guy Earl of Warwick long predates its publication date, and probably dates from around 1592-93.[1] In her introduction to the 2007 Malone Society edition of the play, Helen Moore considered its heroic subject matter, style, and construction,[2] and concluded that it is likely that the play originated c. 1593-94, and was subsequently revised.[3] Katherine Duncan-Jones has noted that there appear to be allusions to the play in Shakespeare's King John, and has concluded that the play must pre-date King John and that it must have been written no later than the mid-1590s.[4]

Helen Cooper of Cambridge University considers the subject matter, stagecraft, and topical references to point to a composition date just after Christopher Marlowe's plays became influential,[5] and that the text of Guy Earl of Warwick reflects Marlowe's "mighty line" and phrasing, so that the play very likely dates to the early 1590s.[6] The similarity of the Guy Earl of Warwick subject to a 1593 play based on the legend of Huon of Bordeaux argues for a date c. 1593-94, and Cooper believes that to be the most likely period of Guy Earl of Warwick's composition.[7] The character of Oberon in the play seems uninfluenced by Oberon as depicted in Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, so Cooper believes it probable that Guy Earl of Warwick was written before A Midsummer Night's Dream (c. 1595-96). [8]

John Peachman, in contrast, cautions that there is no definitive date for Guy Earl of Warwick[9] and proposes that it may have been written in the aftermath of the "Isle of Dogs" affair of 1597.[10] Based on changes in style within the play, Peachman suggests that Guy Earl of Warwick may be a collaborative work and that the comic scenes revolving around the character Philip Sparrow may, in fact, have been written by Ben Jonson in response to criticism Jonson received from Shakespeare over the Isle of Dogs affair.[9][a]

Attribution

The epilogue of Guy Earl of Warwick provides one clue as to authorship: the narrator says, "...For he's but young that writes of this Old Time," and promises better works in the future if the audience will be patient with him.

Guy Earl of Warwick was published by Thomas Vere and William Gilbertson in 1661, and the title page states that the play was written by "B.J." Alfred Harbage states that "B.J." was probably ascribed to falsely imply that the author was Ben Jonson, and so make the play easier to sell.[11] A lost play, "the life and death of Guy of Warwicke" (sic) by Thomas Dekker and John Day was entered in the Stationers' Register in 1620. Based on some stylistic similarities to Dekker's known work, Harbage believes that Guy Earl of Warwick is plausibly, but not definitively, the work of a young Dekker, and that the 1620 play could be a reworking of it,[12] so that Guy Earl of Warwick would be "...the extant original of a lost revision."[13]

Helen Moore states that "...Jonson can be discounted as a possible author...,"[3] and calls the attribution of the play to "B.J." a "spurious ascription" intended to exploit Jonson's popularity at the time the play was published.[14] Guy Earl of Warwick's popular, romantic subject matter, along with stylistic similarities to works by Thomas Dekker (particularly Old Fortunatas)[15] lead Moore to believe that the Guy Earl of Warwick published in 1661 is based on the Dekker/Day play recorded in 1620, which could itself be a revision of a play composed c. 1593-94.[3]

Helen Cooper of Cambridge University writes that because Guy Earl of Warwick would be a work of extreme juvenilia for Ben Jonson, and also possibly a revision of a still older play, Jonson's involvement cannot be discounted.[16] Cooper notes that in Jonson's 1632 play The Magnetic Lady, Jonson describes his ideally bad play in terms that correspond well to the plot of Guy Earl of Warwick,[17] and suggests the possibility that Jonson was, in fact, criticizing his own primitive work.[18]

Surviving Early Copies

Nine early copies of Guy Earl of Warwick are known to exist, all of them are held in the United Kingdom or the United States.[19] One copy was owned by Sir Walter Scott. It contains handwritten comments and underlinings.[20] From the simplicity of the sets and the small number of properties required to perform the play, Helen Moore deduced that the surviving text might have been derived from a touring company's prompt book.[21][b] Helen Cooper notes that publishers Vere and Gilbertson served a "cheap corner" of the publishing market, and she suggests that Guy Earl of Warwick may have been edited to fit their relatively small 48-page volume.[23]

Characters

|

|

|

Plot

Act One: Time (the narrator) explains that Guy has done great deeds in order to win the love of Phillis. Guy tells Phillis that in his selfish pursuit of her love he has neglected God, and that he has determined to travel to Jerusalem and fight the Mohammedans. Phillis beseeches Guy not to go, for the sake of the child she is carrying. Guy leaves, giving her a ring to give to the child if it be a boy. Phillis gives Guy her own wedding ring. Philip Sparrow’s father confronts him about the pregnancy of their neighbor, Parnell Sparling. Young Sparrow refuses to marry her, and announces his plan to join Guy on his journey to the Holy Land.

Act Two: Guy and Sparrow meet a hermit who blesses their journey. Guy and Sparrow reach the Tower of Donather, where an incanter’s spell paralyzes them. They are released from the spell by the music of King Oberon and his fairies. Oberon gives Guy a wand that he uses to dissolve the tower. Then Oberon conducts Guy and Sparrow to the Holy Land.

Act Three: At Jerusalem, Sultan Shamurath and the King of Jerusalem parley regarding the Sultan’s siege of the city. The King refuses to surrender and the Sultan orders an attack. Guy arrives at Jerusalem and fights his way into the city. The tide of the battle turns, Guy captures the Sultan, and converts him to Christianity. The battle won, Guy vows to see the Holy Sepulcher, lay down his arms, and lead a life of peace and repentance.

Act Four: Twenty-one years after Guy left England, his grown son Rainborne leaves England to find him. Now an old man, Guy returns to England. When he departed on pilgrimage, Guy had pledged to remain unknown to his people for 27 years, so he returns unannounced. He is so aged and battle-weary that no one recognizes him.

England has been attacked by the Danes, and King Athelstone and the Danish King Swanus parley at Winchester. Swanus agrees to leave England if Athelstone can find a champion to defeat the Danish giant Colbron. The worried Athelstone wanders at night, and determines to pick the first man he sees to be his champion. The King comes upon Guy and does not recognize him, but Guy convinces him to follow fate and let him fight the giant. Guy takes up arms and slays the giant. He reveals his identity to the King, but requests that no one else learn of his return until his pilgrimage vow is discharged, six years hence. Guy journeys to Warwick, where he will remain incognito and live off the charity of Phillis’ court.

Act Five: Guy lives in a cave near Warwick. He encounters Phillis, and pretends to have been a comrade of Guy’s in the Holy Land. He tells her of Guy’s exploits and, pleased by the news of Guy, she offers him shelter at Warwick Castle. He refuses, saying that he must continue in his pilgrimage. Phillis departs, and Guy thanks God that he was given such a wife. Rainborne meets Sparrow on the Continent. Sparrow tells Rainborne that he and Guy were separated long ago, and that Guy is probably in England now. Rainborne and Sparrow return to England.

One week before his pilgrimage vow will be discharged, Guy is visited by an angel who tells him that he will not survive to see it happen. Torn between his vow and his desire to see Phillis, Guy decides to hold to the vow. He returns to his cave to live out his days in prayer and contemplation.

Rainborne and Herod of Arden prepare for a feast to celebrate the completion of Guy’s pilgrimage. King Athelstone will come to the feast. Rainborne hears a groan and finds Guy in his cave. Guy tells Rainborne that he is near death. He gives Phillis’ wedding ring to Rainborne and asks him to give it to Phillis as compensation for the meals she has given him. Rainborne departs, and Guy dies. Phillis recognizes her ring and hurries to Guy, but is too late. All mourn, and King Athelstone designates suitable monuments to Guy.

Sources

Helen Moore of Oxford University notes that these plot elements of Guy Earl of Warwick are derived from the legend of Guy of Warwick:

- Guy's direction to Phillis to give his ring to their son

- King Athelstone's encounter with Guy at Winchester gate

- Guy's prayer before battle with Colbron

- Guy's last encounter with Phillis

- Guy's encounter with an Angel

- Rainborne's story[24]

Guy's Tower of Donather adventure is derived from the legend of Huon of Bordeaux.[24] The reference to a Dun Cow adventure seems to derive from a lost 1592 ballad, "A pleasant songe of the valiant actes of Guy of Warwicke."[25] The characters of the narrator Time and the clown Philip Sparrow are stock theatrical characters of the time.[26]

Literary Significance

In her 2006 article about Guy Earl of Warwick, Helen Cooper of Cambridge University wrote:

It has been almost entirely overlooked in modern scholarship, perhaps because its topic does not fit with either the classicising or the early modern approaches to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, perhaps because its date of publication lets it fall into the gap between study of the Renaissance and the Restoration. In addition, it does not advance traditional humanist notions of quality or coherence: it has no concern with such niceties as character development, and its second act seems to have wandered in from another play. The verse, however, is always thoroughly capable, and sometimes moving. The text is also of high quality so far as factors such as syntax, metre, and lineation are concerned, and must be close to the author's original. Most importantly, the play is quite remarkably interesting.[27]

Alfred Harbage believes that the original play about Guy of Warwick would have been produced in the early 1590s because plays based on similar heroic legends (e.g., Huon of Bordeaux and Godfrey of Boulogne) were produced around that time.[28] In her introduction to the 2007 Malone Society edition of Guy Earl of Warwick, Helen Moore of Oxford University says that the primary impetus for printing the play in 1661 was simple revival of pre-Restoration drama, but she also notes that Guy Earl of Warwick may have been "particularly congenial" subject matter in the 1660s, when plays often addressed themes of usurpation, restoration, virtue, and recovery.[29] Moore believes that the play as published in 1661 probably "...enhanced the latently tragical elements of the [c. 1593-94] original, possibly playing down in consequence the affinities of the earlier play with historical drama, and favouring instead the theme of penitential piety and spiritual chivalry."[3]

"Philip Sparrow" as a Lampoon of William Shakespeare

Writing in 1941,[30][c] and updating his argument in 1972, Shakespeare scholar Alfred Harbage proposed that "curiously specific information" about Guy Earl of Warwick's Philip Sparrow character pointed to a connection between the character and the real life of William Shakespeare.[32] Sparrow hails from Stratford-on-Avon. He got his girl there pregnant before leaving town (although in the real Shakespeare's case, he married her before leaving). Sparrow describes himself as a "high mounting lofty minded sparrow": Harbage thinks that the "high mounting" part of that phrase would simply be crowd-pleasing double entendre, but he believes the "lofty minded" part may represent "a glancing hit at Shakespeare, written when his mounting star was vexing new writers as well as old."[33] Harbage concludes, "On the other hand, it may not. Of one thing we may be certain: if Guy of Warwick had been published in 1592-1593 instead of misleadingly in 1661, the passage would by now have inspired volumes of commentary" similar to the conjecture over the "Upstart Crow" passage in Robert Greene's Greene's Groats-Worth of Wit.[33] John Berryman, writing in 1960 and building on Harbage's work, argues that because four parts of the attack against Shakespeare found in Groats-Worth - low birth, thievishness, arrogance, and a pun on Shakespeare's name - are also found in Guy Earl of Warwick, it seems likely that the writer of Guy Earl of Warwick was a purposeful imitator of Greene.[34][d]

Helen Cooper agrees that the description of Sparrow "...is too pointed...to be a random formulation...," but she asserts that the character does not necessarily constitute an attack on Shakespeare.[16] She notes that Sparrow once introduces himself as "a bird of Venus," and suggests that this might constitute a connection between the character and the 1593 publication of Shakespeare's long poem, Venus and Adonis.[35] Cooper proposes that the representation of Shakespeare might not be a malicious one,[36] and that it could instead have been intended as a comical allusion, possibly with Shakespeare himself playing the role of Sparrow.[36] Shakespeare's King John contains references to the giant Colbron and to Philip Sparrow (who is not part of the traditional Guy of Warwick legend) in close proximity to each other, which buttresses the argument that Shakespeare was somehow connected to the production of Guy Earl of Warwick.[37] Cooper speculates that if Shakespeare could be connected to the production of Guy Earl of Warwick in some way, it would influence future scholarship regarding plays as diverse as King Lear and A Midsummer Night's Dream.[38] Cooper concludes her piece:

The desire to find Shakespearean memorabilia everywhere properly generates a corresponding skepticism. Yet there comes a point when so many coincidences that cumulatively fit together so well begin to grow to something of great constancy: a point when mere coincidence begins to seem the less likely hypothesis. It is evident that Vere and Gilbertson memorialised something; it becomes difficult not to believe, despite all necessary scepticism, that that something includes Shakespeare.[39]

In 2009, John Peachman explored close textual connections between Guy Earl of Warwick and Mucedorus, the best selling play of the 17th century,[40] but of author unknown. Peachman noted similarities in the plays' plots and characters, and also found several rare phrases that occur in both plays (e.g., the clown character in each play mistakes the word "hermit" for "emmet," a now-archaic name for an ant). Given the rarity of the parallels, that they are all concentrated within a single scene of Mucedorus, and that in each case the lines involve the clown characters of the plays, Peachman concluded that it was very unlikely that the similarities were coincidental.[41] The respective styles of the plays and the fact that the parallels are all contained in a single scene of Mucedorus (but distributed throughout Guy Earl of Warwick) led Peachman to conclude that Mucedorus is the older play.[42] Peachman speculates that the obviousness of the borrowing by the author of Guy Earl of Warwick from Mucedorus may have been intentional. Building on Harbage's work regarding Sparrow-as-Shakespeare, Peachman notes that Shakespeare's King's Men had performed Mucedorus, so that "...the author of the Tragical History could reasonably have expected his audience to associate Mucedorus with Shakespeare," although not necessarily as the play's author.[43] Peachman concludes that Guy Earl of Warwick's borrowings from Mucedorus may have been intended to emphasize to an audience "...that Sparrow was a hit at Shakespeare."[43]

In her introduction to the Malone Society edition, Helen Moore downplays the likelihood that Sparrow is meant to represent Shakespeare. She notes that there are similar clowns in contemporary plays,[44] and that Sparrow's dialogue contains little in the way of Warwickshire dialogue.[45] To the contrary, Sparrow's dialogue is in "essentially the literary southern dialect that was frequently used for comic purposes in early modern drama."[45]

Performance History

There was reference in 1618 to a performance of a play about Guy of Warwick, but it is not known if the reference is to this particular play.[46] Henslowe's Diary indicates that a play about "brandimer" or "brandymer" was performed in 1592. Helen Moore notes that "Brandimart" is another name for the giant Colbron found in Guy Earl of Warwick, and she speculates that the play in Henslowe's Diary might have been on the subject of Guy of Warwick.[47] The title page to the 1661 published version of Guy Earl of Warwick states that it had been "Acted very Frequently with great Applause By his late Majesties Servants." Moore considers it unlikely that it was performed by the "modish" King's Company around 1661, and proposes that it might have been performed by the King's Men, who often performed revivals of older plays.[48]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ Peachman identifies The Two Gentlemen of Verona as the play in which Shakespeare satirizes Jonson.

- ^ At pages vii–xii, Moore discusses how the surviving copies differ as to stage direction, typesetting, and printing.[22]

- ^ E.A.J. Honigmann agreed in 1954 that Harbage's idea could be correct.[31]

- ^ See Greene's Groats-Worth of Wit for a discussion of doubts about Greene's authorship.

References

- ^ Harbage 1972, pp. 143–51.

- ^ Moore 2007, pp. xiv–xv.

- ^ a b c d Moore 2007, p. xxviii.

- ^ Duncan-Jones 2009, p. 71.

- ^ Cooper 2006, p. 121.

- ^ Cooper 2006, p. 125.

- ^ Cooper 2006, p. 127.

- ^ Cooper 2006, p. 124.

- ^ a b Peachman 2009, pp. 570–1.

- ^ Peachman 2009, p. 573.

- ^ Harbage 1972, p. 143.

- ^ Harbage 1972, pp. 143, 146–9.

- ^ Harbage 1972, p. 149.

- ^ Moore 2007, p. xix.

- ^ Moore 2007, pp. xii–xv.

- ^ a b Cooper 2006, pp. 129–30.

- ^ Cooper 2006, pp. 120–1.

- ^ Cooper 2006, p. 129.

- ^ Moore 2007, p. vi.

- ^ Moore 2007, p. vii.

- ^ Moore 2007, p. xii.

- ^ Moore 2007, pp. vii–xii.

- ^ Cooper 2006, p. 123.

- ^ a b Moore 2007, p. xxv.

- ^ Moore 2007, pp. xxv–xxvi.

- ^ Moore 2007, p. xxvi.

- ^ Cooper 2006, p. 119.

- ^ Harbage 1972, p. 144.

- ^ Moore 2007, p. xxvii.

- ^ Harbage 1941.

- ^ Honigmann 1954, p. 17.

- ^ Harbage 1972, p. 151.

- ^ a b Harbage 1972, p. 152.

- ^ Berryman 1999.

- ^ Cooper 2006, p. 130.

- ^ a b Cooper 2006, p. 131.

- ^ Cooper 2006, pp. 131–2.

- ^ Cooper 2006, p. 132.

- ^ Cooper 2006, p. 133.

- ^ & Peachman 2006, p. 465.

- ^ & Peachman 2006, p. 465–6.

- ^ & Peachman 2006, p. 466.

- ^ a b & Peachman 2006, p. 467.

- ^ Moore 2007, p. xvi.

- ^ a b Moore 2007, p. xvii.

- ^ Moore 2007, p. xiii.

- ^ Moore 2007, p. xv.

- ^ Moore 2007, pp. xviii–xix.

Sources

- Berryman, John (1999) [essay dated 1960]. "1590: King John". In Haffenden, John (ed.). Berryman's Shakespeare (Kindle ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 9781466808119.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cooper, Helen (2006). "Guy of Warwick, Upstart Crows and Mounting Sparrows". In Kozuka, Takashi; Mulryne, J. R. (eds.). Shakespeare, Marlowe, Jonson: New Directions in Biography. Hampshire, UK: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0754654427.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Duncan-Jones, Katherine (2009). "Shakespeare, Guy of Warwick, and Chines of Beef". Notes and Queries. 56 (1): 70–2. doi:10.1093/notesj/gjn224. ISSN 0029-3970.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harbage, Alfred (1941). "A Contemporary Attack Upon Shakspere?". The Shakespeare Association Bulletin. 16 (1): 42–9. ISSN 0270-8604. JSTOR 23675372.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harbage, Alfred (1972). "Sparrow from Stratford". In Harbage, Alfred (ed.). Shakespeare Without Words and Other Essays. Rollins Fund Series. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674803954. OCLC 341197.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Honigmann, E. A. J., ed. (1954). King John. The Arden Shakespeare. London: Methuen. OCLC 4183737.

- Moore, Helen (2007). "Introduction". In Moore, Helen (ed.). Guy of Warwick, 1661. The Malone Society Reprints. Vol. 170. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719077098. OCLC 156816060.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Peachman, John (2006). "Links between Mucedorus and The Tragical History, Admirable Atchievments and Various Events of Guy Earl of Warwick". Notes and Queries. 53 (4): 464–467. doi:10.1093/notesj/gjl158. ISSN 0029-3970.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Peachman, John (2009). "Ben Jonson's "Villanous Guy"". Notes and Queries. 56 (4). Oxford University Press: 566–74. doi:10.1093/notesj/gjp197. ISSN 0029-3970.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Cooper, Helen (20 April 2001). "Did Shakespeare play the Clown?". Times Literary Supplement. No. 5116. pp. 26–7.

External links

- The Tragical History of Guy Earl of Warwick—Text at the University of Virginia Library