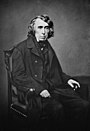

Benjamin Robbins Curtis

Benjamin Robbins Curtis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office October 10, 1851 – September 30, 1857 | |

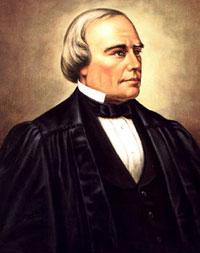

| Nominated by | Millard Fillmore |

| Preceded by | Levi Woodbury |

| Succeeded by | Nathan Clifford |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 4, 1809 Watertown, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | September 15, 1874 (aged 64) Newport, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Political party | Whig (before 1854) Republican (1854–1874) |

| Spouse(s) |

Eliza Woodward

(m. 1833; died 1844)Anna Scolley

(m. 1846; died 1860)Maria Allen (m. 1861) |

| Children | 12 |

| Education | Harvard University (BA, LLB) |

Benjamin Robbins Curtis (November 4, 1809 – September 15, 1874) was an American attorney and United States Supreme Court Justice. Curtis was the first and only Whig justice of the Supreme Court. He was also the first Supreme Court justice to have a formal legal degree and is the only justice to have resigned from the court over a matter of principle. He successfully acted as chief counsel for the Impeachment of U.S. President Andrew Johnson during the first presidential impeachment trial and is notable as one of the two dissenters in the Dred Scott decision.[1]

Biography

Benjamin Curtis was born November 4, 1809 in Watertown, Massachusetts, the son of Lois Robbins and Benjamin Curtis, the captain of a merchant vessel. Young Curtis attended common school in Newton and beginning in 1825 Harvard College, where he won an essay writing contest in his junior year. At Harvard, he became a member of the Porcellian Club. He graduated in 1829, and was a member of Phi Beta Kappa.[2] He graduated from Harvard Law School in 1832,[3] and was admitted to the bar later that year.[4]

In 1834, he moved to Boston where he joined the law firm of Charles P. Curtis. Practicing in that maritime city allowed Curtis to develop expertise in admiralty law, and he also became known for his familiarity with patent law.[5]

In 1836, Curtis participated in the Massachusetts "freedom suit" of Commonwealth v. Aves on behalf of the defendant.[6] When New Orleans resident Mary Slater went to Boston to visit her father, Thomas Aves, she brought with her a young slave girl about six years of age, named Med. While in Boston, Slater fell ill and asked her father to take care of Med until she (Slater) recovered. The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society and others sought a writ of habeas corpus against Aves, contending that Med became free by virtue of her mistress' having brought her voluntarily into Massachusetts. Aves responded to the writ, answering that Med was his daughter's slave, and that he was holding Med as his daughter's agent. Curtis was one of the attorneys who argued the case on behalf of Aves.

The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, through its Chief Justice, Lemuel Shaw, ruled that Med was free, and made her a ward of the court. The Massachusetts decision was considered revolutionary at the time. While previous decisions ruled that slaves voluntarily brought into a free state, and who resided there many years, became free, Aves was the first decision which held that a slave voluntarily brought into a free state became free from the first moment of arrival. The decision in this freedom suit engendered controversy and helped to alienate the South. It was in contrast to the Dred Scott decision, in which Curtis participated as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court.[7]

Curtis became a member of the Harvard Corporation, one of the two governing boards of Harvard University, in February 1846. In 1849, he was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives.[8] Appointed chairman of a committee to reform state judicial procedures, they presented the Massachusetts Practice Act of 1851. "It was considered a model of judicial reform and was approved by the legislature without amendment."[9]

At the time, Curtis was viewed as a rival to Rufus Choate, and was thought to be the preeminent leader of the New England bar. He came from a politically-connected family, and had studied under Joseph Story and John Hooker Ashmun[10] at Harvard Law School. His legal arguments were thought to be well-reasoned and persuasive. He was a Whig and in tune with their politics, and Whigs were in power. As a potential young appointee, he was thought to be the seed of a long and productive judicial career. He was appointed by the president, approved by the Senate, elevated to the bench, but was gone in six years.[11]

Curtis had 12 children and was three times married.[12]

Supreme Court service

Curtis received a recess appointment to the Supreme Court on September 22, 1851 by President Millard Fillmore, filling the vacancy caused by the death of Levi Woodbury. Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster persuaded Fillmore to nominate Curtis to the Supreme Court, and was his primary sponsor.[12] Formally nominated on December 11, 1851, Curtis was confirmed by the United States Senate on December 20, 1851, and received his commission the same day. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1854.[13]

He was the first Supreme Court Justice to have earned a law degree from a law school. His predecessors had either "read law" (a form of apprenticeship in a practicing firm) or attended a law school without receiving a degree.[12][14]

His opinion in Cooley v. Board of Wardens 53 U.S. 299 (1852)[15] held that the Commerce Power extends to laws related to pilotage. States laws related to commerce powers can be valid so long as Congress is silent on the matter. That resolved a historic controversy over federal interstate commerce powers. To this day, it is an important precedent for resolving disputes.[12] The court interpreted Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the US Constitution, the Commerce Clause. The issue was whether states can regulate aspects of commerce or Congress retains exclusive jurisdiction to regulate commerce. Curtis concluded that the federal government has exclusive power to regulate commerce only when national uniformity is required. Otherwise, states may regulate commerce.[14]

Dred Scott v. Sandford and resignation from the Court

Curtis was notable as one of the two dissenters in the Dred Scott case, in which he disagreed with essentially every holding of the court. He argued against the majority's denial of the bid for emancipation by the slave Dred Scott.[16] Curtis stated that, because there were black citizens in both Southern and Northern states at time of the drafting of the federal Constitution, black people thus were clearly among the "people of the United States" countenanced by the fundamental document. Curtis also opined that because the majority had found that Scott lacked standing, the Court could not go further and rule on the merits of Scott's case.[12]

Curtis resigned from the court on September 30, 1857 because he was exasperated with the fraught atmosphere in the court engendered by the case.[14][17] As one source puts it, "a bitter disagreement and coercion by Roger Taney prompted Benjamin Curtis's departure from the Court in 1857."[18] However, others view the cause of his resignation as having been both temperamental and financial. He did not like "riding the circuit," as Supreme Court Justices were then required to do. He was temperamentally estranged from the court and was not inclined to work with others. He was not a team player, at least on that team. The acrimony over the Dred Scott decision had blossomed into mutual distrust. He did not want to live on $6,500 per year, much less than his earnings in private practice.[19][20][21]

Although he was a Supreme Court justice for only six years, Curtis is generally considered to have been the only outstanding justice on the Taney Court in its later years other than Taney himself.[12] He is the only Justice of the Supreme Court to have resigned on a matter of principle.[12]

Return to private practice

Upon his resignation, Curtis returned to his Boston law practice, becoming a "leading lawyer" in the nation. During the ensuing decade and a half, he argued several cases before the Supreme Court.[10]

In 1868, Curtis acted as chief defence counsel for the Impeachment of U.S. President Andrew Johnson during the impeachment trial. He read the answer to the articles of impeachment, which were "largely his work". His opening statement lasted two days, and was commended for legal prescience and clarity.[10][22] He successfully persuaded the Senate that an impeachment was a judicial act, not a political act, so that it required a full hearing of evidence. This precedent "influenced every subsequent impeachment".[12][14]

After the impeachment trial, Curtis declined U.S. President Andrew Johnson's offer of the position of U.S. Attorney General.[10] A highly recommended candidate for the Chief Justice position upon the death of Salmon P. Chase, Curtis did not receive the appointment.[10] He was the unsuccessful Democratic candidate for U.S. senator from Massachusetts in 1874.[22] From his retirement from the bench in 1857 to his death in 1874, his aggregate professional income was about $650,000.[10]

Death and legacy

Curtis died in Newport, Rhode Island, on September 15, 1874. He is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery, 580 Mount Auburn Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts.[23][24] On October 23, 1874, Attorney General George Henry Williams presented in the Supreme Court the resolutions submitted by the bar on Curtis' death and shared observations on Judge Curtis' defense of President Andrew Johnson in the articles of impeachment against him.[25]

Curtis' daughter, Annie Wroe Scollay Curtis, married (on December 9, 1880) future Columbia University President and New York Mayor Seth Low.[26] They had no children.

Published works

- Reports of Cases in the Circuit Courts of the United States (2 vols., Boston, 1854)

- Judge Curtis's Edition of the Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States, with notes and a digest (22 vols., Boston: Little Brown & Company, 1855).

- Digest of the Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States from the origin of the court to 1854 Little Brown & Co., (1864).

- Memoir and Writings (2 vols., Boston, 1880), the first volume including a memoir by Curtis's brother, George Ticknor Curtis, and the second "Miscellaneous Writings," edited by the former Justice's son, Benjamin R. Curtis, Jr.[10][22]

See also

References

- ^ "Famous Dissents - Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857)". PBS. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- ^ "Supreme Court Justices Who Are Phi Beta Kappa Members" (PDF). Phi Beta Kappa. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ Harvard Law School (1890). "Quinquennial Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the Law School of Harvard University, 1817-1889". Google Books. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ^ Davis, William Thomas (1895). "Bench and Bar of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Volume 1". Google Books. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ^ A Memoir of Benjamin Robbins Curtis, LL. D.: Memoir (1879), p. 84.

- ^ Commonwealth v. Aves, 18 Pick. 193 (Mass. 1836).

- ^ "Commonwealth v. Aves". Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ^ "The Political Graveyard".

- ^ "Benjamin Robbins Curtis, Timeline of the Court". Supreme Court Historical Society. Archived from the original on March 20, 2010. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Benjamin R. Curtis, Jr., ed. (October 19, 1879). "Judge Benjamin R. Curtis, A Memoir of Benjamin Robbins Curtis, LL.D. With Some of his Professional and Miscellaneous Writings" (PDF). The New York Times.

- ^ Leach, Richard H. (December 1952). "Benjamin Robins Curtis, Judicial Misfit". The New England Quarterly. Vol. 25, no. 4. pp. 507–523. JSTOR 362583.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fox, John. "The First Hundred Years: Biographies of the Robes, Benjamin Robinson Curtis". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780-2010: Chapter C" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Benjamin Curtis". michaelariens.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ Cornell Law School, full text of Cooley v. Board of Wardens 53 U.S. 299 (1852).

- ^ See, s:Dred Scott v. Sandford/Dissent Curtis

- ^ "Roger B. Taney". michaelariens.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ Vining Jr., Richard L.; Smelcer, Susan Navarro; Zorn, Christopher J. (January 26, 2010). "Judicial Tenure on the U.S. Supreme Court, 1790-1868: Frustration, Resignation, and Expiration on the Bench". Emory Public Law Research Paper (06–10): 9, 10. SSRN 887728.

- ^ Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L., eds. (1969). The Justices of the Supreme Court, 1789–1969: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Vol. II. pp. 904–05.

- ^ Dickerman, Albert (January–February 1890). "The Business of the Federal Courts and the Salaries of the Judges". American Law Review. 24 (1): 86.

- ^ Van Tassel, Emily Field; Wirtz, Beverly Hudson; Wonders, Peter. "Why Judges Resign: Influences on Federal Judicial Service, 1789 to 1992" (PDF). National Commission on Judicial Discipline and Removal, Federal Judicial Center. pp. 13, 66, 123, 130. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 1, 2010. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c Wilson, James Grant. Benjamin Robbins Curtis.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Christensen, George A. "Here Lies the Supreme Court: Gravesites of the Justices". Supreme Court Historical Society 1983 Yearbook. Archived from the original on September 3, 2005. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- ^ Christensen, George A. (February 19, 2008). "Here Lies the Supreme Court: Revisited". Journal of Supreme Court History. 33 (1). University of Alabama: 17–41.

- ^ Williams, George H. (1895). Occasional Addresses. Portland, Oregon: F.W. Baltes and Company. pp. 120–124.

- ^ "Seth Low" by Gerald Kurland, New York, Twayne Publishers, 1971

- Benjamin Robbins Curtis at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Flanders, Henry. The Lives and Times of the Chief Justices of the United States Supreme Court. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1874 at Google Books.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Huebner, Timothy S.; Renstrom, Peter; coeditor. (2003) The Taney Court, Justice Rulings and Legacy. City: ABC-Clio Inc. ISBN 1-57607-368-8.

- Leach, Richard H. Benjamin Robins Curtis, Judicial Misfit. The New England Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Dec., 1952), pp. 507-523 (article consists of 17 pages) Published by: The New England Quarterly, Inc.

- Leach, Richard H. Benjamin R. Curtis: Case Study of a Supreme Court Justice (Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 1951).

- Lewis, Walker (1965). Without Fear or Favor: A Biography of Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Simon, James F. (2006) Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney: Slavery, Secession, and the President's War Powers (Paperback) New York: Simon & Schuster, 336 pages. ISBN 0-7432-9846-2.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

External links

- Benjamin Robbins Curtis at Find a Grave

- Fox, John, 'The First Hundred Years, Biographies of the Robes, Benjamin Robinson Curtis. Public Broadcasting Service.

- New Publications, Judge Benjamin R. Curtis, A Memoir of Benjamin Robbins Curtis, LL.D. With Some of his Professional and Miscellaneous Writings, Edited by his son, Benjamin R. Curtis, (October 19, 1879). The New York Times.

Template:Start U.S. Supreme Court composition Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1851–1852 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1853–1857 Template:End U.S. Supreme Court composition

- 1809 births

- 1874 deaths

- 19th-century American Episcopalians

- 19th-century American judges

- 19th-century American politicians

- American Unitarians

- Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Harvard Law School alumni

- Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

- Freedom suits in the United States

- Massachusetts lawyers

- Members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives

- Massachusetts Whigs

- People from Watertown, Massachusetts

- United States federal judges appointed by Millard Fillmore

- Recess appointments

- Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- United States federal judges admitted to the practice of law by reading law

- American memoirists